1968: A Memoir Only Slightly Disguised as Fiction

Today, on my birthday, I’m grateful to have lived through those years and the decades since.

For months we had been bombarded on television with horrendous, uncensored images of the war in Vietnam. In March, American soldiers massacred 347 at My Lai. Two weeks later, President Lyndon Baines Johnson, the target of anti-war rage, said he would not seek re-election. In April, Martin Luther King had been assassinated on the balcony of a Memphis Hotel, and the inner cities exploded. Just days later SDS students at Columbia barricaded themselves in the president’s office while black students occupied a separate building. In May, Parisian students went on strike, tearing up the cobblestones of Paris. A few weeks later, moments after victory in the California primary, Bobby Kennedy was murdered in the kitchen of a Los Angeles Hotel. A few days before, a marginal member of Andy Warhol’s circle, Valerie Solanas, also founder of SCUM, the Society for Cutting Up Men, shot him in the stomach. Prior to the shooting, she had written a manifesto calling for “systematically fucking up the system, selectively destroying property, and murder.”

It was June of 1968. And Sarah was on the Illinois Central, heading downtown, on a humid morning shortly after her wedding. She’d been on her way downtown to apply for a passport — they were going to Europe on their honeymoon — when something in her perception altered. All spring she’d begun to feel her sense of safety in the world compromised. But it was subtle — a tendency to listen to her own heartbeat, a bit of unease when she woke up in the morning. Then, on the train, those vague feelings of unease took a more palpable shape. One moment she was sitting there, in the unfocused state that characterizes most experience, hardly noticing her surroundings, not really thinking of anything at all. And then, without warning, she was suddenly aware of becoming faint. Sarah had never actually fainted in her life, but once, when she was ten and had a stomach flu, she almost had, and she’d never forgotten the feeling-of sounds growing more and more distant, tiny spots accumulating in her field of vision, threatening to overtake her sight, the clarity of her senses abandoning her. She’d been on the brink of losing consciousness when she’d thrown up, and immediately felt better.

On the train, over ten years later, the physical sensations of impending loss of consciousness hadn’t gotten anywhere near what she’d felt at school that day, but she’d felt sure that’s where they were heading. The rumble of the train seemed to come through cotton in her ears, and instead of simply seeing things, she became aware of her vision itself, which now seemed to be holding the world together like a Seurat painting, a painting that she was certain was going to decompose into thousands of tiny particles. She was going to faint, she knew it — and the thought that this was happening was as terrifying to Sarah as if she were going to die. She looked around, as if to find relief somewhere, but couldn’t; everything on the train, from the imitation leather seats to the people themselves, seemed old and worn and ugly. “I’ve got to get out of here,” she thought. The need was so strong that nothing else mattered, not the bewildered faces of the other passengers, or the frightened look on the conductor’s as she clutched his arm. He suggested she put her head between her knees, but Sarah knew there was only one remedy. “Please, please, I just have to get off this train. I have to. Can you get them to stop it?” So they did, and the conductor helped Sarah to Union station, where her senses began to clear, and she called her fiance Simon to come get her.

In their small South Side apartment, snuggled under her mother’s orange and green quilt, watching “General Hospital,” Sarah felt briefly better, but something new, which would be constant, ever-present for almost a year, had attached itself to her-the fear of it happening again. She tried to banish the idea from her mind, to get back to how she had felt a moment before, immersed in Luke and Laura’s problems, but found it was impossible. And she began to stew about what she would do if “it” did happen again would she grab at people, babble like an idiot, make a terrible scene?

The next day, as she got ready to go to work, she began to think about the five blocks to Book Express, five blocks she had routinely traversed with barely a thought, and which now seemed like a boundless ocean that lay between one safe habor — her home — and another — the bookstore. As long as she could imagine being able to tum back and run home, should it happen again, she felt relatively calm. Book Central, where the books themselves felt like comforting friends and she knew Jack Cohen, the manager, had a crush on her, felt safe, too. But there were all those streets between, and as she got to the end of the first street and was about to cross it to the other, the space between the two curbs grew wide, like a movie pan in which a broad vista suddenly opens up. Her body felt odd, numbish. Soon, if she kept going, she’d be in the middle of the ocean, having swum too far from one shore to go back but still too far away from the other to reach it in time, should anything terrible happen to her. Her skin grew clammy, and her heart began to beat irregularly. Am I having a heart attack now? What’s happening to me? She turned around. By the time she reached her apartment, she was drenched with sweat and collapsed into Simon’s arms.

The next day, she asked Simon to walk her to work; the next, to accompany her to the comer grocery shop; the next, to come with her while she belatedly applied for the passport. Even as she was filling in the forms, going through the motions, Sarah knew she’d never be able to get on the plane, unless something miraculously cured her in time. The fear of it happening had rapidly became attached to a whole variety of venues malls, crowded stores, busy streets, empty streets, crowded elevators, empty elevators, large, open spaces, small, cramped spaces, and-of course-trains. The sphere of safety grew smaller and smaller. She quit her job, and at a certain point, even their own apartment no longer felt sheltering. Eating, once her solace, became difficult, and one day she noticed that when she ate, he left hand was clenched in a fist. She lost twenty pounds, and stopped wearing a bra; she felt she couldn’t breathe freely with one on.

Simon insisted she see a therapist. She wound up seeing several. The first, a Freudian, noting that she was not wearing a bra or make-up, immediately zeroed in on Sarah’s “inability to accept her feminine role” now that she was married. The second--the only woman she saw — took out a pad of paper, on which Sarah expected her to record a full history of her symptoms, turned to her and flatly asked, “Do you have orgasms?” The third was a psychiatrist, a cold, dark-suited rail of a man who prescribed a regimen of anti-psychotic drugs that made Sarah’s tongue thick and her brain feel like it was stuffed with cotton.

Then, on the fourth try, she found Dr. Silber. He was one of those dignified but homey Jewish men of Sarah’s father’s generation who looked like they could just as easily have been rabbis as professionals. Tall, slightly stout but well-built, bald, with a face that was not quite handsome but nice to look at; he invited Sarah to sit down and tell him about herself. When she launched into a description of her symptoms-something that always gave her an odd kind of relief — he stopped her. “Let’s save that for a bit later. For now, tell me some other things — -where you come from, your family, what your life was like before all thi s happened, and so on.”

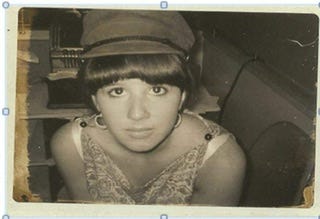

Sarah, at first, found it surprisingly hard to reconstruct her past. Her present life was so dominated by minute-to-minute hyper-awareness of her own body, anticipations, fears, that reaching back to any time before the train incident felt like she was entering someone else’s life. As far as her childhood went, she didn’t want to even think about it, much less talk about it. Not about her hyper-critical, rage-filled father or her depressed mother, who’d never learned to drive a car and whose many physical complaints were continually dismissed by her doctors as hypochondria. Nor did she want to talk about the eight-year old, overweight and shy, who loved putting words together in poems. By ten, the teachers had discovered she had “talent” and began making her read the work out loud to a snickering class. So of course, she gave it up. Instead, like a samurai in training, Sarah methodically transformed herself, body and soul, into a perky pre-teen, abandoning her Tchaikovsky records for Fabian and Ed “Kookie” Byrnes, and Louisa May Alcott for Annette Funicello. She tamed her unruly hair in by setting it in huge rollers, and put tissue paper in her bra to look more like a curvy mouseketeer.

As the fifties crashed into the sixties, it suddenly became more important to be “cool” and political than to be curvaceous. In awe of the hip, male authors and radicals who dominated popular culture at that time, Sarah discovered there were ways to be a writer and be admired by the boys at the same time: sarcasm, cynicism, and lots of dirty talk. Her “coming-out” piece was a parody of a neighborhood newspaper called “The Jewish News.” It got her sent her the principal’s office for ethnic offense, but dazzled the only people who counted at that time in her life: the boys. Her ambition in life was to be the next Norman Mailer.

In high school, when she was still a virgin, she’d fallen in love with a boy in her class who was much “faster” than she was. At parties, he’d play around with Sarah, trying to see how far he could go; she’d pretty much let him do whatever he wanted, short of actual intercourse. But she knew she was just a side diversion. He had two other girlfriends, with whom he had regular sex — one a long-limbed, hip-talking, Black girl with a guitar and a wonderful singing voice, the other a frizzy-hair politico, several years older, who was instrumental in founding the Newark chapter of SDS. Sarah was in awe of these girls, who were accomplished in all the ways that really counted, while she was always just short of the mark: cute but not in the right way (Judy Collins, not Sandra Dee, had suddenly become the ideal,) “hip” tastes in literature and music but much too serious about her schoolwork, all the correct political ideas but mistrustful of ideologues. And most of all, too vulnerable, too yearning, too sensitive. Not cool.

When she finally had intercourse with Curtis, on her seventeenth birthday, home on break from college, in the attic apartment of one of his SDS friends, it was awful. Sarah was extremely nervous, to be completely naked in front of him, but he didn’t even seem to be looking at her at all. He was stoned, and when he took the rubber out of its package (about five minutes after they’d taken their clothes off,) he ripped too hard and it went flying across the room. Curtis found this hysterically funny. He leaped out of bed, retrieved the rubber, and, bounding back into bed like a child on a trampoline, smacked Sarah jovially-but quite hard — on her thigh. The sex itself lasted three minutes. Then he got up and put his clothes on to join the bluegrass session downstairs. Afterwards, she’d gone out to Ming ‘s with her girlfriends, for chow mein and to celebrate the end of her virginity. By then, she’d almost convinced herself that she’d had a great time with Curtis. It was good to have done the thing, anyway, to finally get it out of the way.

Sarah had applied to the University of Chicago because it had a reputation for being intellectual and hip. In her first semester, she received a “D” on her first critical essay, because she “dared” (as the teacher wrote on her piece) to liken King Lear to her own father. Later that fall, she watched her roommate nearly die from a botched illegal abortion. In the spring, one of her professors became annoyingly flirtatious. Sarah, like everyone else at the time, did not think there was anything wrong with student/teacher affairs, but she was put off by the way his eyes would glisten as he talked to her, as though he were surveying something edible. And he was ugly. When, after some perfunctory chit-chat about the pre-Socratics, he’d asked her to dinner, she said no, appreciatively but firmly. From that moment on, he took every opportunity to needle her-about her politics, her love life, her clothes.

One day, in an open doorway in full view of a classroom full of (male) students waiting for a class to begin, he’d slapped Sarah on the bottom; “Time for class, dear,” he’d smirked, jovially. Sarah, at first, couldn’t believe that he’d actually done it. The last person to smack Sarah’s behind had been her father; she was five, and annoying the men at her father’s pinochle game, pulling on their pants legs under the table. Professor Dilman’s little whack, about a tenth as hard as her father’s, made her feel five again. “What?. …” She’d been speechless, her face hot with humiliation. “Oh, Sarah, don ‘t be so sensitive, Dilman replied, and walked into the classroom, smiling, shaking his head. Sarah ran down the hall and went straight to the department chair, who okayed her request to drop out of class on the condition that she cite “personality differences,” as the reason. She didn’t have a problem with that; there was no sexual harassment in 1968. When, a few months later, the Dean took back her scholarship, arguing that it could be used to keep a young man out of Vietnam, Sarah saw nothing wrong with his reasoning.

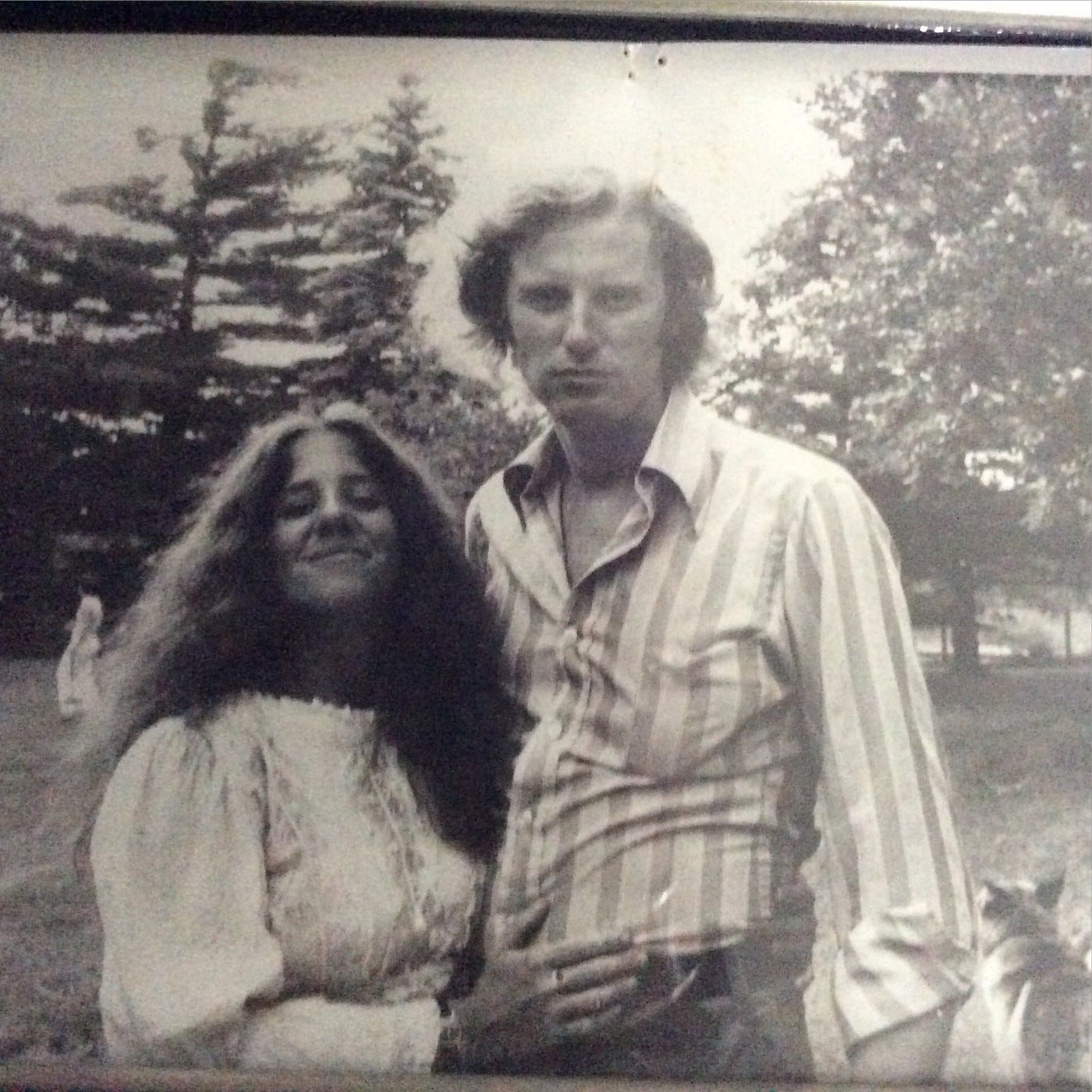

Dropping out of school had seemed liberating at first, to be free of droning professorial voices and always having to read what was assigned to you. She liked having a paycheck, paltry though it was, and enjoyed her two housemates, a divorced faculty wife and an Australian exchange student in psychology. But by the time Simon had come into the bookstore, with his rimless glasses, goatee and patched-elbow tweed jacket-the unmistakable signs of professordom — Sarah felt tired and soiled, from too many drunken nights and too many regretful mornings, cooking breakfast for one guy or another that she’d fallen into bed with. Plus, Simon recognized her from the part-time job she had briefly held, doing editorial work for an economics journal, and Sarah was gratified to have someone acknowledge that she was something more than a sales-clerk. “You ‘re the one who was always reading that awful left-wing crap,” he said — and it felt like a compliment.

For a while, it was delightful simply to be a part of the couple buying the Sunday Times rather than the one selling it, and to be situated-if only by romantic association- on the other side of the faculty/student divide. Simon adored having a smart girlfriend to take to faculty parties, and was particularly pleased that Sarah could keep up the banter with his mentor, Milton Friedman, the guru of the “new economics.” On her part, Sarah tried hard to overlook the fact that her husband and his friends were just the kind of people her own friends — former SDSers now drifting into the Weather Underground and just-sprouting radical women’s groups — saw as the enemy. She was suspicious of the groupthink and coercive ideologies spreading through left politics. But the other extreme, which her new husband inhabited, was just as creepy. The week after she moved into his townhouse, Simon suggested that because the “opportunity cost” of his doing the dishes was far greater than Sarah’s — he being a well-paid professor and she unemployed at the time — it was only rational that she be the family dishwasher. Another time she overheard Simon and his colleagues, who were lounging in the living room, drinking beer and smoking pipes, doing a cost-benefit analysis of mass extermination of the Black Panthers. There was nothing racist about it, Simon explained; it was simply a thought experiment.

By the time that they were married, just six months later, she was already feeling as though she’d walked into a trap — although who had set it she couldn’t exactly say. “Believe it or not,” she told Dr. Silber, “I knew it was all wrong even while I was walking down the aisle. “The Bach was playing, the rabbi was waiting, and all I could think of was running away. After the wedding, my father took my sister and a bunch of my friends over to Coney Island, and I wanted to go with them, rather than with Simon! But, you know, I was in a kind of fog, I just sort of let things carry me along. When I think back to that week-end, I remember Sergeant Pepper playing all the time on the radio, and every time I heard any of the songs, it felt like a requiem for my freedom and ….I don’t know …some lost dream of some sort. I still can’t hear it without all those feelings corning back.”

And so it was that she found herself, in June, on the Illinois Central, going to downtown Chicago for a passport that she would never use. When, in August, the city she lived in erupted in the chaotic violence of the Democratic National Convention, she was already too immersed in her own misery to muse, as she would years later, about the synchronicity of her own nervous breakdown and that of the country around her. The “personal” and the “political” were still disparate realms in her analysis, and by now she had far less interest in the violence downtown than the rhythm of her own heartbeat. Other people in her apartment hooted, shouted, cheered, and jeered while Sarah lay, curled up on the couch, feeling like an invalid who had long given up her investment in any kind of revolution. She didn’t even notice it when, just a few weeks later, the first major demonstration of the Women’s Liberation Movement — the “No More Miss America” protest — was held in her home state of New Jersey, in Atlantic City, where her father had sometimes driven the family, to take refuge from the summer Newark heat, and to do a little gambling.

One day, Dr. Silber asked a truly surprising question: “Would you mind if I read some of your writing?” Sarah picked a paper on Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, another on Sartre’s concept of “The Look,” and just for fun — a review she’d done of “Bonnie and Clyde.” The session after he read the pieces, Dr. Silber came into the waiting room, took Sarah’s two hands in his own, and looked into her eyes like a parent about to deliver a lecture to a disobedient but adored child.. He said her name two times, shook his head, then: “You’re a writer. We’ve got to get you writing again.”

It was June of 1971, and the sixties were over. By now, the Beatles had broken up. Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix were dead. 4 students had been slain by national guardsmen at Kent State. And Richard Nixon was president. But Kate Millet had published Sexual Politics. Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch. Shulamith Firestone, Dialectics of Sex, Robin Morgan, Sisterhood is Powerful. Toni Cade, The Black Woman. Maya Angelou, Now I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Nikki Giovanni, Black Talk/Black Judgement. My therapist’s advice was no longer the heretical prescription it would have been in 1968. My marriage would limp along for a few more years — and with it, my agoraphobia. But the recovery began at that moment.

I really enjoyed reading this. Happy Birthday!

Susan, this is very well written and heartfelt. As a woman of the same generation, I can relate to so much of what you lived through. What popped out to me was, how few of life's tools we had back then compared to what my 12 year old granddaughter has now. Happy Birthday and best of luck to you in all you do.