Natalie Dormer Opens Up About Anne Boleyn and “The Tudors”

We clicked immediately—and her contract with Showtime was over, so she felt free to speak her mind about Anne, feminism, the distortions of history, and the making of “The Tudors.”

[An excerpt from my book The Creation of Anne Boleyn.]

…Natalie Dormer, the 26 year-old actress who was chosen to play the role of Anne Boleyn, approached her assignment very differently from Jonathan Rhys Meyers. A long-time British history buff who had, in fact, hoped to study history at Cambridge (she misunderstood a question on her A-level exams and failed to get the necessary grade for acceptance,) Natalie has strong opinions about the real Anne, and when she got the role, was excited over the prospect of embodying her as accurately as possible. “I didn’t want to play her as this femme fatale—she was a genuine evangelical with a real religious belief in the Reformation.”[1]

Dormer also came to the role well aware of the stereotypes and gender biases that had dogged Anne, both in her lifetime and in later representations:

“Anne really influenced the world, behind closed doors,” she told me in our 2010 interview. “But she’s given no explicit credit because she wasn’t protected. Let’s not forget, too, that history was written by men. And even now, in our post-feminist era we still have women struggle in public positions of power. When you read a history book, both the commentary and the first hand primary evidence, all the natural gender prejudices during the period will certainly be there…

…Anne was that rare phenomenon, a self-made woman. But then, this became her demise. The machinations of court were an absolute minefield for women. And she was a challenging personality, who wouldn’t be quiet and shut up when she had something to say. This was a woman who wasn’t raised in the English court, but in the Hapsburg and French courts. And she was quite a fiery woman and incredibly intelligent. So she stood out—fire and intelligence and boldness—in comparison to the English roses that were flopping around court. And Henry noticed that. So all the reasons that attracted [Henry] to her, and made her queen and a mother, were all the things that then undermined her position. What she had that was so unique for a woman at that time was also her undoing.”[2]

I was extremely lucky to meet Natalie after her contract with Showtime was over, and she felt free to cease acting as a spokesperson for the show and to speak her mind. We arranged to meet in a small, boutique hotel in Reading, the London suburb where she grew up and still lived at the time. When she arrived, the staff immediately sprang into action to make things comfortable for us in the bar; she clearly is the town celebrity. But, except for her dramatic expressiveness and striking beauty, which singled her out from everyone else at the bar, there was no aura of celebrity about her. Despite her success and the legions of fan clubs devoted to her, she regarded herself then as very much at the start of her career, and seemed genuinely excited to talk to someone else who was waist-deep in the world of Anne Boleyn, a place that she had occupied with intensity and dedication over the last several years. For over an hour and half, accompanied by her younger sister Samantha, we shared our love of Anne and her story, lamented how it had been misrepresented both in Anne’s time and our own, discussed Tudor history, and reflected on the struggle of Anne, women actors, and young women today to escape the limitations and expectations placed on them. It was in this interview that Natalie revealed, for the first time, just how hard she had struggled to “not betray” Anne, as she put it, in the series.[3]

The first challenge came almost immediately. Natalie had auditioned in her natural hair color, which is blonde, fully expecting that if she got the role she would play Anne as a brunette. She knew her history, and it never occurred to her that the executives at Showtime would have anything else in mind. She was concerned, in fact, that her strong physical differences from Anne—including her blue eyes—would disqualify her for the part. She reassured herself about the eyes—“they aren’t the right color, but just like Anne, I’ve been told they are my most becoming feature” (actually, there’s not a feature on Natalie’s face that isn’t dazzling.) But she knew the hair would have to be changed. So after she received the phone call telling her she’d won the part—largely on the basis, Hirst told me, of the “physical chemistry” between her and Rhys Meyers (Natalie describes it as “a lot of heaving bosom stuff”), after becoming “hysterical with joy,” she immediately dyed her hair.[4]

When she arrived on set, Dee Corcoran, chief of the hair department, who won an Emmy for her work on the show and was “almost like an Irish mother” to Natalie, took her aside. “Okay, we’ve got a really serious problem—you dyed your hair. They are really unhappy. Really unhappy.”[5] “They” were the Showtime execs.

“So they sent me back to the hairdresser and they tried to dye blonde back in. But any hairdresser will tell you that it doesn’t work to put peroxide blonde on jet black. I looked like a badger! I was terrified that I’d lose the role. I mean, what did they have planned, now that I was multi-colored—to put me in a blonde wig?” Dormer wasn’t sure she could accept that. “Anne’s hair color is such an important detail! For one thing, it was the basis of a lot of nasty labels—Wolsey calling her the “night crow” and so on. And also, in being a confident brunette she was defying the ideal, of what it meant for a female to be attractive at that time.”[6]

“So we’re all barely cast, and I went to Bob Greenblatt with my heart in my mouth, and told him how important it was that Anne be dark. ‘Bob, I have to play her dark. It’s so important. You have to let me play her dark!’ Some might say I was being melodramatic and self-important. But I thought it would just be a direct betrayal of Anne. Of her refusal to step into the imprint of the acceptable norm at the time.”[7]

“Greenblatt, who is a very shrewd man, just said ‘I’ll think about it.” I assumed I’d lost the job. I felt completely and utterly depressed. But then I got a phone call a few days later, telling me that Bob had decided I could be dark.”[8]

Natalie didn’t try to hide her pride and pleasure from me: “It was a major coup at the time! A major coup!”[9] It was clear that by “coup” Natalie didn’t mean that she had bested the executives with a power play, for she was well aware that they called the shots, and that her casting had hung precariously in the balance. It was, rather, a victory for the values that she hoped would be brought to the series—authenticity, a recognition of what was unusual about Anne, and a willingness, on the part of those in charge, to listen and learn.

But there were more challenges ahead. […..]

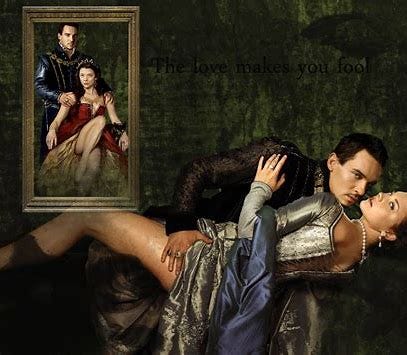

Michael Hirst, in his zeal to make the series deliciously digestible to prime-time viewers, did not initially do justice to Natalie’s view of Anne. Although in his interview with me, he described her as “one of the heroines of English culture…who did a great deal to support and foster the advancement of the Protestant faith” but whose “name has been blackened because she was the Other Woman, who came between Henry and his rightful queen,” the Anne of the first season of The Tudors (and part-way into the second) did not do much to disrupt that “blackened” image.[10] Through that first season, Anne entices, provokes, and sexually manipulates her way into the queenship, allowing Henry to get to every base except home, driving him mad with pent-up lust. “Seduce me!” she orders Henry, and a moment later we see her stark naked[11]; a few episodes later, she taunts him to find a piece of ribbon that she has apparently hidden inside her vagina. In the last episode of the season, they ride into an appropriately moist and verdant forest, tear at each other’s clothing, and just about do it before Anne pulls herself away from the embrace, leaving him to howl in frustration—and reminding me, unpleasantly, of high school.

At the beginning of season two, it is also suggested that while at the French court, Anne slept with half the courtiers, and possibly the French king. When he presents her, newly anointed as Marquesse of Pembroke, to Francis and his court, she performs a Salome-style dance that makes one wonder just which historical series one is watching. At home, her bold flirting, confiding, and cuddling with Mark Smeaton makes the later charges of adultery with him quite plausible—and completely out of character with Anne, who was obsessed with being accepted as Queen and would never have condescended to treat a court musician in such an openly familiar fashion.

[This hyper-sexualization of Anne] inevitably led to recycling the image of Anne Boleyn as the seductive, scheming Other Woman. That’s the classic soapy element of the story, after all: sexpot steals husband from mousy, menopausal first wife. Hirst says he never intended this, and attributes it less to the script than to “deep cultural projections.” He had initially seen Anne, he told me, as a victim of her father’s ambitions, and believed he was writing the script to emphasize that. He was surprised when “critics started to trot this line out: ‘here she is, just a manipulative bitch.’ Well, actually I hadn’t written it like that. But they couldn’t get out of the stereotypes that had been handed down to them and that’s what they thought they were seeing on the screen. It didn’t matter what they were actually seeing. They had already decided that Anne Boleyn was this Other Woman, this manipulative bitch.”[12]

I agree with Hirst about power of the history of cultural images; but it’s odd that he would be so naive about the way that the show’s own imagery reinforced them. Dormer believes it was indeed unconscious on Hirst’s part, that in capitalizing on the sexual chemistry between Henry and Anne, and while portraying Katherine as so virtuous and long-suffering, he slipped into a very common male mind-set:

“Men still have trouble recognizing,” she told me “that a woman can be complex, can have ambition, good looks, sexuality, erudition, and common sense. A woman can have all those facets, and yet men, in literature and in drama, seem to need to simplify women, to polarize us as either the whore or the angel. That sensibility is prevalent, even to this day. I have a lot of respect for Michael, as a writer and a human being, but I think that he has that tendency. I don’t think he does it consciously. I think it’s something innate that just happens and he doesn’t realize it.”[13]

Natalie was in a bind:

“I had to reconcile the real person and the character of Anne Boleyn as created in the text. For the actor, the text is your bible. You can try to put a spin on the nuances, but in the end our job is to be the vehicle of the text.” Yet she often felt “compromised” by the way Anne’s character was written for the first season, and got tired of “flying the flag of Showtime” in interviews, justifying the show’s hyper-sexuality and inaccuracies “when in the pit of my stomach, I agreed wholly with what the interviewer was saying to me. I lost many hours of sleep, and actually shed tears during my portrayal of her, trying to inject historical truth into the script, trying to do right by this woman that I had read so much about. It was a constant struggle, because the original script had that tendency to polarize women into saint and whore. It wasn’t deliberate, but it was there.”[14]

At the point at which I spoke to Michael Hirst, after the last season of the show was completed, he had become much more aware of the long legacy of negative stereotypes of Anne, the tendency of fiction-writers and some historians to simply re-cycle them, and his own complicity. But at the time of the first reviews, he was surprised when some critics “dismissed Anne as your typically manipulative, scheming bitch” and was distressed that “some of this criticism hurt Natalie very much.”[15] But Natalie wasn’t about to let it rest with that. During a dinner with Hirst, while he was still writing the second season, she shared her frustration and begged him “to do it right in the second half. We were good friends. He listened to me because he knew I knew my history. And you know, he’s a brilliant man. So he listened. And I remember saying to him: `Throw everything you’ve got at me. Promise me you’ll do that. I can do it. The politics, the religion, the personal stuff, throw everything you’ve got at me. I can take it.’”[16]

She told Hirst of her wish that audiences, when the series got to Anne’s fall, would empathize with her. Talking to me in Reading, Natalie was especially passionate about that subject.

“It happened very shortly after she miscarried, remember. To miscarry is traumatic for any woman, even in this day and age. And to be in that physical and mental state, having just miscarried, and be incarcerated in the Tower! If only she’d had that child! It’s horrific to confront how much transpired because of terrible timing, and how different it could have been. It’s one of the most dramatic “ifs” of history. And it’s why it’s such a compelling, sympathetic story. But I knew by the time we’d finished the first season that we hadn’t achieved it. That audiences would have no sympathy for her, because the way she’d been written, she would be regarded as the other woman, the third wheel, that femme fatale, that bitch. Who had it coming to her.”[17]

Hirst listened to her and took her seriously, and the result was a major change in the Anne Boleyn of the second season. Still sexy, but brainy, politically engaged and astute, a loving mother, and a committed reformist. Scenes were added, showing Anne talking to Henry about Tyndale, instructing her ladies-in-waiting about the English Bible, quarrelling with Cromwell over the mis-use of monastery money. No longer was Anne simply a character “in the ether.” Rehabilitating her image became part of Hirst’s motivation in writing the script:

“I wanted to show that she was a human being, a young woman placed in a really difficult and awful situation, manipulated by her father, the king, and circumstances, but that she was also feisty and interesting and had a point of view and tried to use her powers to advance what she believed in. And I wanted people to live with her, to live through her. To see her.”[18]

The execution scene was especially important to Natalie: “By the end of the season, when I’m standing on that scaffold,” she told Michael, “I hope you write it the way it should be. And I want the effect of that scene to remain with viewers for the length of the series. I want the audience to be standing with her on that scaffold. I want those who have judged her harshly to change their allegiance so they actually love her and empathize with her.”[19] However the scene was scripted, this would require a lot of Natalie herself, especially since the show was not filmed in chronological sequence, and the execution scene was shot first, before the episodes that led up to it. At dawn, standing in the courtyard of Dublin’s Kilmainham Jail, the site of many actual executions, she had “a good cry” with Jonathan Rhys Meyers. “It was incredibly haunting and harrowing—I felt the weight of history on my shoulders.” But because she had “lived and breathed Anne for months on end,” and had “tremendous sympathy for the historical figure,” it did not require a radical shift of mood to prepare herself for the scene.

“I was a real crucible of emotions for those few days. By the time I walked on to the scaffold, I hope I did have that phenomenal air of dignity that Anne had.” Anne’s resigned, contained anguish did not have to be forced, because by then, Natalie was herself in mourning for the character: “As I was saying the lines, I got the feeling I was saying good-bye to a character. And when it was over I grieved for her.”[20]

Hirst, too, recalls the heightened emotions of shooting that scene: “That was an amazing day. Extraordinary day. After, I went in to congratulate her. She was weeping and saying, `She’s with me Michael. She’s with me.’”[21]

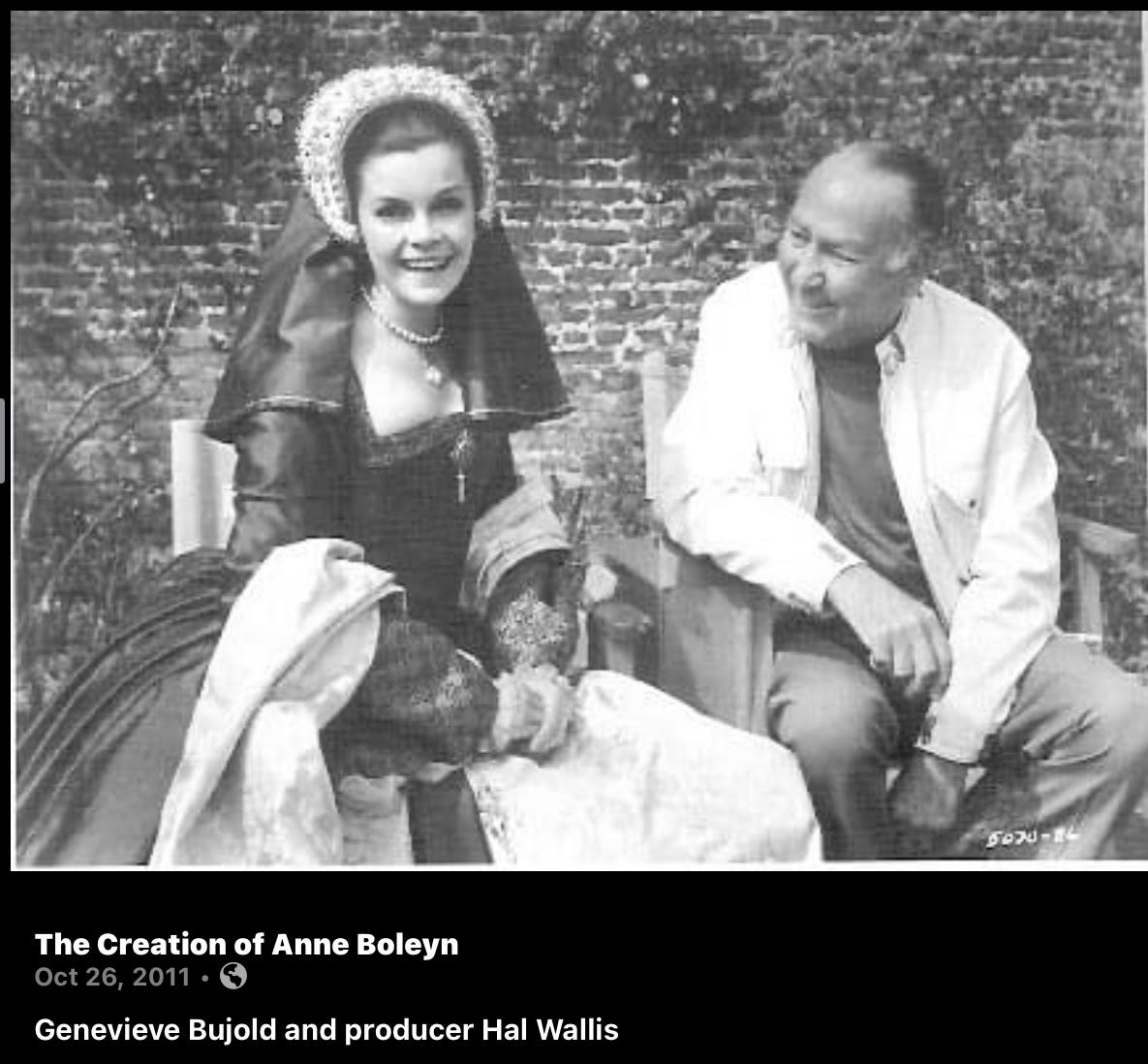

The episode averaged 852,000 viewers, according to Nielsen, an 83% increase over the first season finale and an 11% increase over the season premiere, and for many viewers—particularly younger women—the execution scene became as iconic as Genevieve Bujold’s “Elizabeth Shall be Queen” speech.[22] When I showed the episode to a classroom of historically sophisticated honors students, none of whom had watched the series, there were many teary eyes; among devoted Tudors fans, for whom it was the culmination of a building attachment to the character, the effect of the scene—whose last moments were both graphic and poetic, lingering on Anne post-execution, her now-lifeless face still bearing her final sad, unbelieving expression, caught mid-air, suspended in space—was emotionally wrenching

Many viewers, in fact, watched the show listlessly after Anne/Dormer left; the rest of the story seemed anti-climatic to them. “Natalie Dormer basically ruled The Tudors!,” wrote one, “Her performance was absolutely passionate, genuine and convincing and that’s why I was devastated when her character died and she left the show.”[24] The feelings of the last commentator were shared by many. The following season’s finale had the show’s second smallest audience (366,000 viewers), and among those who stuck with it and continued to enjoy it (as I did), there remained a void where Natalie’s Anne Boleyn had been. The ads for the remaining two seasons were successively more sensationalizing—the third season depicting Henry sitting on a throne of naked, writhing bodies, the last season described (on the DVD) as a “delicious, daring…eight hours of decadence.”[25] But “those of us who were glued to this sudsy mix of sex and 16th century politics know the spark went out of the series when Dormer’s Anne Boleyn was sent to the scaffold,”[26] wrote Gerard Gilbert in UK’s The Independent.

Today, hundreds of fan-sites are devoted to Natalie Dormer, who managed, despite being cast on the basis of “sexual chemistry,” to create an Anne Boleyn that is seen by thousands of young women as genuinely multi-dimensional. Natalie still gets letters from them, every day, and finds them gratifying, but also a bit depressing. “The fact that it was so unusual for them to have an inspiring portrait of a spirited, strong young woman—that’s devastating to me. But young women picked up on my efforts, and that is a massive compliment—and says a lot about the intelligence of that audience. Young girls struggling to find their identity, their place, in this supposedly post-feminist era understood what I was doing.”[27]

For more on my book, The Creation of Anne Boleyn, click here.

Coming soon: My interview with Genevieve Bujold.

[1]-[9] Natalie Dormer, interview by author, Richmond Upon Thames, England, 31 July 2010)

[10] (Michael Hirst, interview by author, telephone, Lexington, Ky., 28 April 2011)

[11] This all takes place in a dream of Henry’s, side-stepping any charges of historical inaccuracy.

[12] (Michael Hirst, interview by author, telephone, Lexington, Ky., 28 April 2011)

[13] (Natalie Dormer, interview by author, Richmond Upon Thames, England, 31 July 2010)

[14] (Ibid.)

[15] (Michael Hirst, interview by author, telephone, Lexington, Ky., 28 April 2011)

[16] (Natalie Dormer, interview by author, Richmond Upon Thames, England, 31 July 2010)

[17] (Ibid.)

[18] (Michael Hirst, interview by author, telephone, Lexington, Ky., 28 April 2011)

[19] (Natalie Dormer, interview by author, Richmond Upon Thames, England, 31 July 2010)

[20] (Ibid.)

[21] (Michael Hirst, interview by author, telephone, Lexington, Ky., 28 April 2011)

[22] (Nordyke 2008)

……..

[24] (Boddin, Bernadette. 2011. The Creation of Anne Boleyn on facebook, September 10. http://www.facebook.com/thecreationofanneboleyn)

[25] Taken from promotional material found on The Tudors, Season 3 DVD case

[26] (Gilbert 2011)

[27] (Natalie Dormer, interview by author, Richmond Upon Thames, England, 31 July 2010)

Interesting stuff. I remember how good The Tudors was back in the day and enjoyed it. Always fun to hear about some of the details behind the scenes.