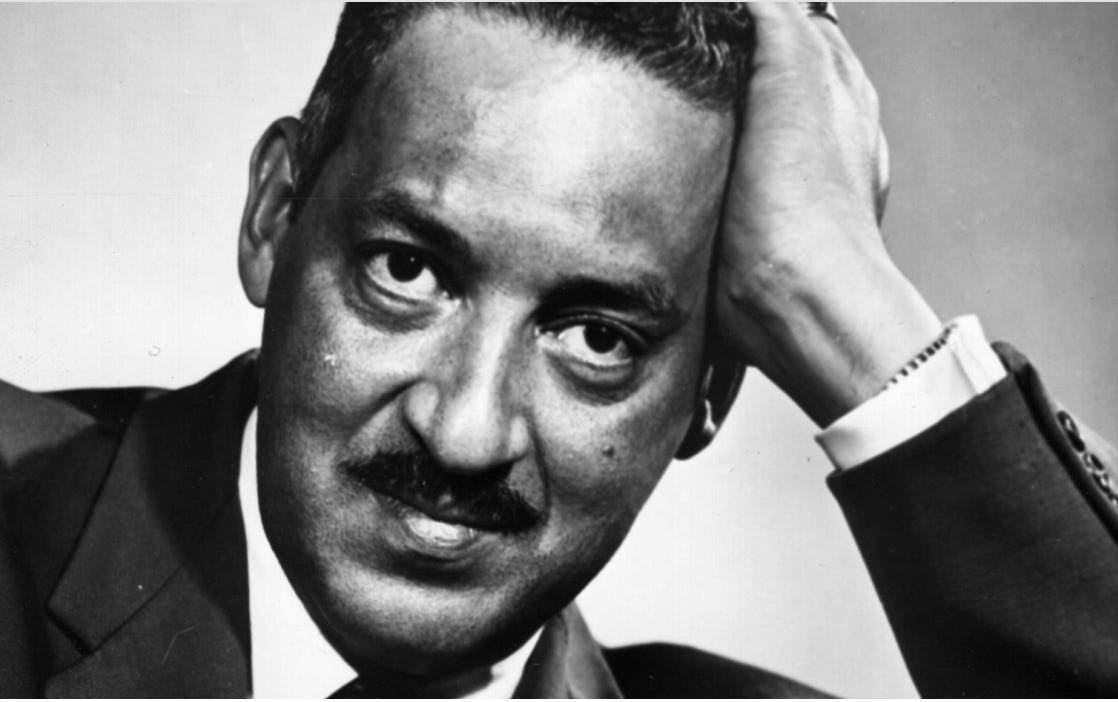

Appreciating Thurgood Marshall

Just because it’s good to be reminded of the kind of courage that we need from our courts today.

One of the most startling and disturbing lessons of the Trump years for me was recognizing how much I had underestimated the degree to which the very keepers of the law, from the lowest courts to the Attorney General and the Supreme Court, could be put into the service, not just of racism or sexism or homophobia (that much I knew) but into a blatant, outright assault on the separation of powers that presumably protected us from dictatorship or monarchy. That protection, we were told by our teachers, was our Democracy’s defining feature, our supreme achievement. We might have to struggle to make sure that equal justice under law was dispensed to all, but surely the principle that no one was above the law was firmly embedded in our institutions.

Today, the jury is out on that. Our most hallowed institutions are far more fragile than I was taught. With that recognition in mind, when Politico asked me and other historians to name candidates for a new monument to greatness, I immediately thought of Thurgood Marshall. Along with the Notorious RBG, he represents for me the quintessential warrior for the rights under seige by today’s SCOTUS.

I was seven years old in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled on Brown V. the Board of Education, the collective name given to the five cases challenging the constitutionality of “separate but equal” education. The decision was a landmark not only in blasting apart Plessy V. Fergusson but in its innovative use of social science and psychology to demonstrate the pernicious effects of racism on the souls of both black and white children. Newspapers and magazines hailed Thurgood Marshall as “Mr. Civil Rights,” and he made the cover of Time Magazine. The brutal backlash that followed Brown, televised for the entire nation to see, turned a struggle seen by many Northerners as a “Southern thing” into a social movement.

I had no awareness of the significance of the ruling until I saw those faces on the TV, contorted with hatred, spitting poison at the Black teenager walking down the path to Little Rock’s Central High. Although there was plenty of racism in my Newark, New Jersey neighborhood, Blacks and Whites were together in the classroom and on the athletic field. “Segregation” was an abstraction to me, and the name “Thurgood Marshall” meant nothing. By the time that I had become more politically conscious, other names dominated my list of heroes and events: Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, sit-ins, marches, boycotts. By then, like other white teenagers at the time, I considered the law a sluggish, “establishment” instrument of social change.

I had a lot to learn. The law may be slow-moving, but “establishment” it needn’t be—in the right hands. Marshall, as a law student at Morehead and young lawyer working for the NAACP, had been taught by his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston that the law was a “weapon” in the battle for equality—“if you know how to use it.”

Marshall did. The fourteenth amendment was his inherited artillery, but he understood that the words themselves were not capable of conferring equal protection under law. That protection has to be fought for—on a multitude of fronts and with every disciplinary tool at the legal warrior’s disposal.

Other lawyers scoffed when, arguing for Brown, he brought psychologist Kenneth Clark in to testify about his experiments with a pair of dolls, identical in every way except for color. Black and white school children had been asked a series of questions: which is the nice doll? Which is the bad doll? Which doll would you like to play with? The majority of black children, Clark reported, attributed the positive characteristics to the white doll, the negative characteristics to the black doll. When Clark asked one final question, “Which doll is like you?” the children looked at him, he says “as though he were the devil himself” for putting them in that predicament. Northern children often ran out of the room; southern children looked ashamed and embarrassed. Clark recalled one little boy who laughed, “Who am I like? That doll! It’s a nigger and I’m a nigger!” It’s a testimony that still has power, even in the 21st century, when I played video of it for a classroom of freshman in a course on social movements of the sixties.

Marshall also understood the intersections that some contemporary theorists seem to feel is their singular discovery. As a Supreme Court Justice arguing for Roe V. Wade, he stressed that the burdens and risks of illegal abortions fell disproportionately on the backs of poor women. (Were he alive today, he would undoubtedly find the Dobbs decision appalling.) As a young lawyer, he fought hard against poll taxes and other forms of voter suppression. But he also believed that the vote will not be truly democratically deployed until other forms of discrimination—in education and employment, for example—are abolished. As a Supreme Court Justice, his arguments against the death penalty emphasized not only that it was “cruel and unusual punishment” but disproportionately meted out to Black men.

Looking back at his arguments from the vantage point of 2024, it’s clear that Marshall was not just an innovative thinker, and, as Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan described him, “the greatest lawyer of the 20th century.” but in many ways ahead of his time. While most prominently known as a fighter for racial justice he deepened and broadened our understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment in ways that would serve reproductive rights, LGBTQ rights, worker’s rights, and the very concept of “equality” itself. Yet in the sixties, younger activists dismissed him as not being radical enough and when I teach the 1950’s and 1960’s to college students, they rarely have heard of him. Like other innovators from the 50’s and 60’s, he left a huge historical footprint, yet the man himself has been eclipsed by more visible, dramatic forms of activism.

“Every day,” wrote an editorial in the Washington Afro-American after Marshall’s death, “we live with the legacy of Justice Thurgood Marshall.” Let us not forget that legacy, as we desperately wish for the day when what he represented will be revived.

Thanks for this! Nice to be reminded.

A man whose legacy I truly admire & appreciate. As life for me would be a lot harder without his presence.