At the Ellipse

They keep saying “We don’t know enough about her.” They keep asking “But how would she govern?” She’s been telling us all along. And never clearer than Tuesday night at the Ellipse.

That Other Day

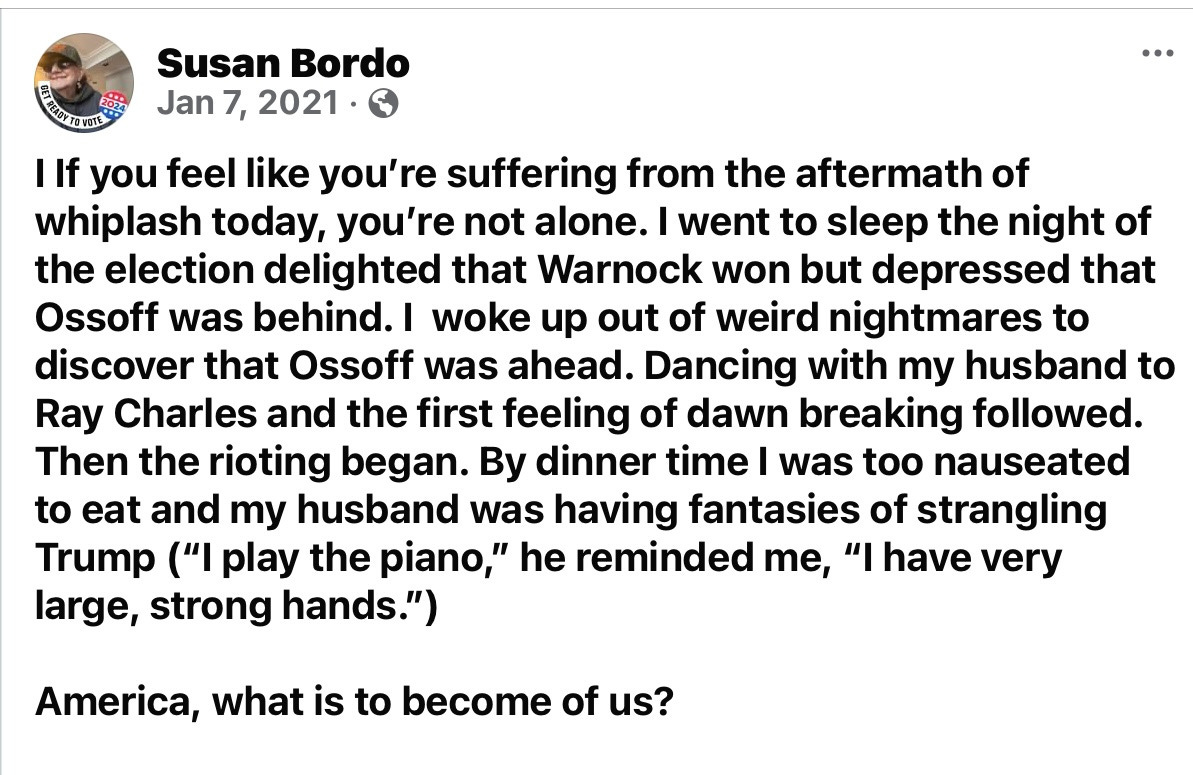

It began with such hope. We went to sleep the night before knowing that Raphael Warnock had won a historic victory in Georgia, making him the first Black Democratic senator from Georgia and the first Black Democratic senator from the South. By the end of the next day, Jon Ossoff had joined him, putting Democrats in control of both chambers of Congress. A Black man. A Jewish man. And both so talented, so brilliant. On social media, we exchanged gifs of blue balloons with “Yay!” On them.

By the next morning, I’d posted on Facebook:

I’m still asking that question.

Ellipse

The word itself sounds metaphysical, poetic, mysterious. Geometrically, it’s our orbit around the sun. The perfect oval simplicity and wholeness of an unbroken egg. The shape of a lovely green park in front of the White House where children search for Easter eggs.

In grammar, an ellipse is an absence that is full of meaning: words clearly understood without having to be explicitly stated. Dot, dot, dot. Between one speech and another, anxiety, confusion, anger, terror, and a strange new kind of radical uncertainty. A few transient dots of hope and relief. And then, dot, dot, dot.

We are standing in the middle of those dots. How will the sentence end? We used to know after the votes were counted. We can’t even be sure of that any more.

She never said the word “Democracy.”

Plenty of commentators have used the word “Democracy,” referring to what they see (rightly) is at stake in the election. But Kamala Harris herself didn’t use that word in her Ellipse speech. She spoke of freedom. She spoke of decency and fairness. She talked about “the promise of America” as if it were a family sitting at dinner, shouting at each other in heated argument, then breaking up in laughter over familiar, shared memories. “We like a good debate, don’t we? We like a good debate!”

But Kamala never talked about “Democracy,” that bulky abstraction that has been intoned so many times in our lives, from the boring social studies teacher to Joe Biden’s earnest speeches to the “never-Trumper” Republicans describing their choice to vote for Kamala Harris, that it has become drained of living meaning—a big, rhetorical placeholder for everything in our lives now under threat. It’s for rousing anthems that we sing in assembly, not really knowing what we’re singing about. For all its felt relation to our lives, it may as well be “amber weighs a grain.”

She never used the word “Fascist,” either. Political caution, for sure. But not just that. Every time I heard that word this election season, I remembered how indiscriminately and arrogantly young leftists (I include myself here) flung that word around in the sixties, and although it is absolutely appropriate to call out the threat of fascism now, I wondered how many viewers had the faintest idea what it meant. (Yes, it’s disturbingly accurate, as General Kelly acknowledged—but I’m talking communication.) Like “Democracy,” “Fascism” is another Big One, and unlike “Democracy,” a lot of people grow up never having even heard it in school, let alone had it explained to them.

But a major “closing argument” isn’t the place for a lecture.

Paint a picture of the man instead, “unstable, obsessed with revenge, consumed with grievance, and out for unchecked power.,” sowing division and fear of each other among us. When he was told the mob was out to kill Mike Pence, he said “So What?” He has a list of enemies. He plans to throw them in jail. He’s “consumed” with grievance, “obsessed” with revenge. He wants you divided and afraid of each other. Can you see his ugly, hateful face? But now, I am looking at a beautiful woman, and she has reduced the vengeful redeemer, the releaser of the nation’s Id, the mirror of the worst of men, to a small, small thing. She reminds us that power has and can still be taken away from him:

"Nearly 250 years ago, America was born when we wrested freedom from a petty tyrant. Across the generations, Americans have: Preserved that freedom. Expanded it. And in so doing, proved to the world that a government of, by, and for the people is strong and can endure. And those who came before us - the patriots at Normandy and Selma. Seneca Falls and Stonewall. On farmlands and factory floors. They did not struggle, sacrifice, and lay down their lives, only to see us cede our fundamental freedoms, only to see us submit to the will of another petty tyrant.”

The choice is not between two weighty words—Democracy/Facism—but between a “petty tyrant” who would imprison his enemies and a leader who would offer them a “seat at the table.” At that family dinner. The ghosts of those who came before us are there, too—“the patriots at Normandy and Selma, Seneca Falls and Stonewall”—and they don’t always agree, any more than we agree now. So let’s argue! Debating is good. Shouting is permitted. This isn’t a club only for people who fold their napkins a certain way.

But you’ll need to accept the smell of unfamiliar spices.

She Didn’t Roar “I Am Woman”

But consider her imagery. Her mother’s yellow formica table, where she sat late at night, cup of tea in hand. It’s not that men don’t stay up late at night, worrying over bills. But unless they are British, they probably have coffee or scotch rather than tea, and I’ve never been with a man who regarded the kitchen table as “his.”

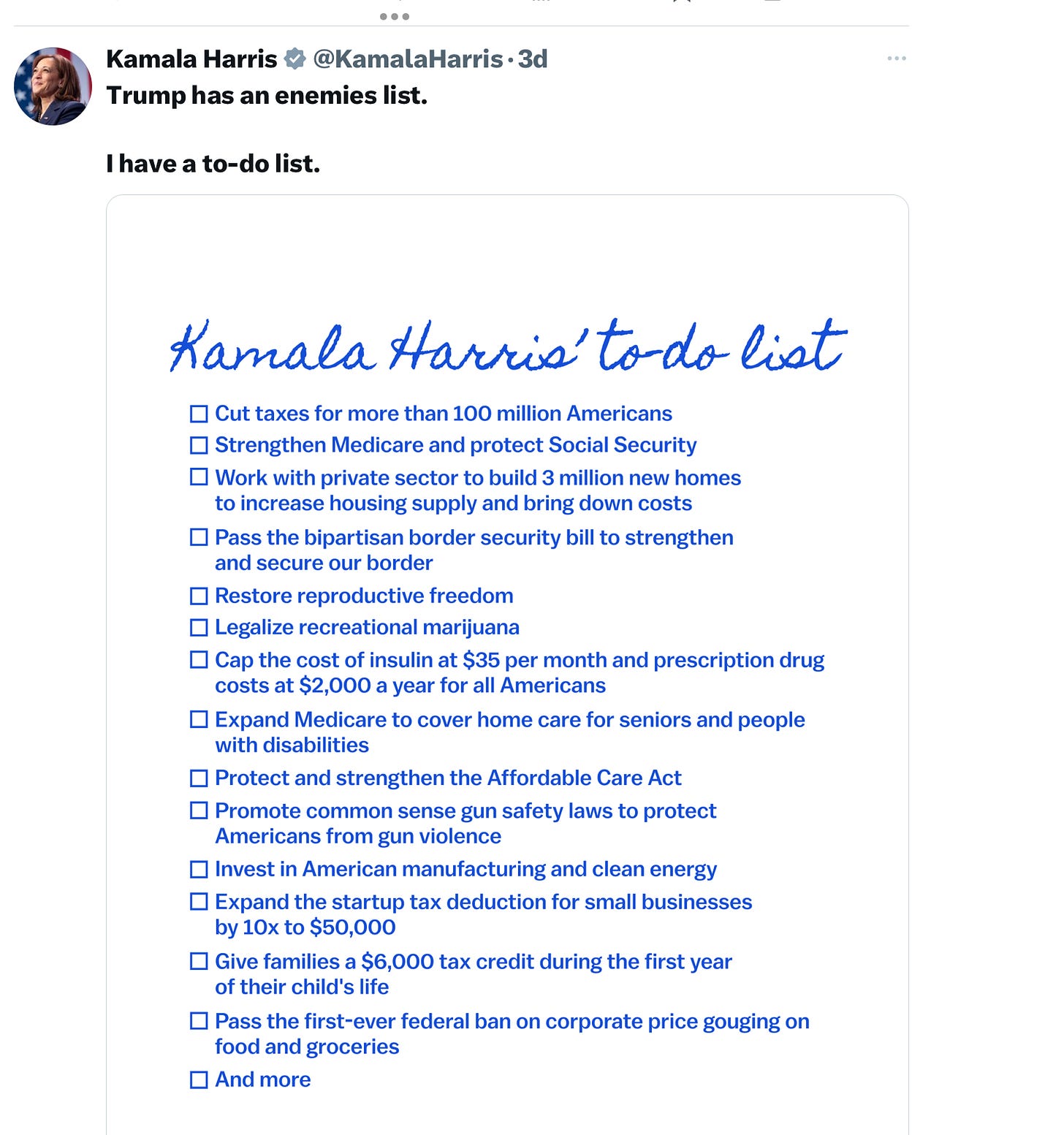

Do men have lists of “things to do”? I’m sure some have—my own husband Edward, for example, does—but mine is on the fridge, clipped onto a magnet which I remove occasionally to use to secure half-full popcorn bags, and his is on the back of an envelope. Kamala’s will be on the Resolute desk.

When her mother was dying, she tried to find food that her mother would relish and clothes that wouldn’t irritate her skin. It’s not that men don’t care for their dying parents. But when Kamala describes skin-soothing clothing, she rubs her fingers together with a tactile memory of choosing the tenderest garments and imagining how they would comfort her fragile mother. I picture her late at night, sitting at her own table, writing, searching for the right detail—which she includes in virtually all her rallies—that would make a visceral connection with listeners.

As it did for me: Our older sister had the most sensitive skin, even when she was healthy, and when Binnie and I shopped for presents for her birthday, not being “itchy” was primary. When Mickey was barely walking, I spent hours leafing through the “Soft Surroundings” catalogue, searching for soft, flowing but not-too-long caftans that my sister wouldn’t trip on as she stumbled to the bathroom but that would wrap her in some small measure of pleasure when she sat down again. I was so anxious to find the right thing I ordered six of them in different styles.

My mother, briefly emerging from a coma, asked for jello. The nurses brought some. “It’s good,” she said. They may have been her last words, I don’t know, I was living far from her at the time.

My father’s last words to me: “Cover me, doll. Cover me.”

Vessels

“These United States of America, We are not a vessel for the schemes of wannabe dictators.” (Kamala Harris)

“We are more than baby-making vessels” (Michelle Obama)

You may think I’m going too far; my students often accused me of that. And perhaps, as a philosophy student, I read too many religious, misogynist (and yes, fascist) tracts. But “vessel” brings to my mind (and apparently to Michaelle Obama’s too) the ancient notion that the function of women is to serve as mute incubators and bringers-forth of future life. “Vessels” for the continuance of the race. It’s now being pulled from the pages of 16th century texts by Alito and Vance.

Were such associations deliberate on Kamala’s part? Was Kamala’s unconscious making the connection? Did she insert the-country-as-vessel after hearing Michelle’s speech? I don’t know and I don’t care. I care that she turned Trump’s Hitlerian Fatherland into a protesting Motherland.

No, you will not turn our bodies into mute vessels again. No, you will not turn our vibrant country into an obedient handmaid for your schemes.

“Rights” Are Not Enough

“We must shift from a focus on individual rights to a focus on connectedness and relationships in order to create a more just and inclusive society” (Carol Gilligan)

“[F] or as long as I can remember, I have always had an instinct to protect. There’s something about people being treated unfairly or overlooked that frankly just gets to me.” (From Kamala Harris’s speech at the Ellipse.)

Until I started to think about this piece, I was baffled by what I thought might be a wrong turn in the way Kamala Harris’s campaign approached abortion.

Remember this moment?

What a “brava” moment for Kamala that was! I’m sure hundreds of thousands of women jumped up from their couches, pumped their fists, shouting “YES”!! For many of us, it was the moment we began to get interested—really interested—in Senator Harris. Was there a new, brilliant, unafraid-to-show-your-feminism champion in town?

In the hearing, Kamala framed the abortion issue the way I’d always seen it: not as about “choice” or “privacy” but a matter of equal treatment under the law. The double-standard is strewn throughout our legal system, which values bodily autonomy so highly that no one can be forced to take a simple blood test (for blood or bone compatibility, for example)—not even when the life of another person hangs in the balance. Yet centuries of ideology and legal decisions have allowed for—and often forced—women’s bodies to be controlled and invaded, supposedly in the interests of fetal life.

We don’t hear much about the equality issue anymore, however. As the consequences of Dobbs and the Trump abortion bans have shown themselves to be even more dire than foreseen, the fight for reproductive freedom has shifted its focus from equality and “choice” to threats to women’s lives, health, and future fertility. At the DNC and campaign rallies, women tell of bleeding on their bathroom floors, traveling long distances with raging infections, having to wait until they are close to death before doctors, afraid of being jailed, are willing to treat them.

While such post-Dobbs horrors aren’t as rare as people might have expected, the vast majority of abortions are not sought to intervene in a health crisis, and I wondered if the emphasis on emergency care was obscuring the role that women’s reproductive freedom plays in economic (not just physical and emotional) health—for men as well as women.

As Laura Tyson writes

For women, abortion is a cornerstone of economic freedom. Reproductive justice is economic justice. In the US, the nationwide legalization of abortion under Roe v. Wade was essential to a half-century of women’s economic advancement – and the advancement of their children and families. It allowed women to plan and balance their families and careers, choosing when to have children and how many. It enabled women to complete school, which increased their lifetime earnings. It also contributed to a significantly higher labor-force-participation rate for women, which rose from 43% in 1970 to 57% in 2024 (after a sharp but short-lived decline to 54.6% during the COVID-19 pandemic, when women dropped out of the workforce to shoulder care responsibilities for their children and elders). The female labor-force participation rate is a major determinant of economic growth in the US and around the world….

Laura Tyson, “Abortion and Reproductive Rights are Economic Issues,” in Project Syndicate, September 20, 2024)1

All of this means reproductive “issues” are issues for men as well as women—and not just because of their emotional ties with women and girls. Unplanned pregnancy, it’s true, has the most proximate economic consequences for women, who may be forced to quit jobs, halt progress toward higher education, or avoid jobs that offer greater possibilities for promotion and higher pay but require them to be on call for bosses rather than babies. But every limitation on a woman’s ability to bring income into the family also places a greater economic burden on husbands and partners.

(For more on abortion as an economical issue):

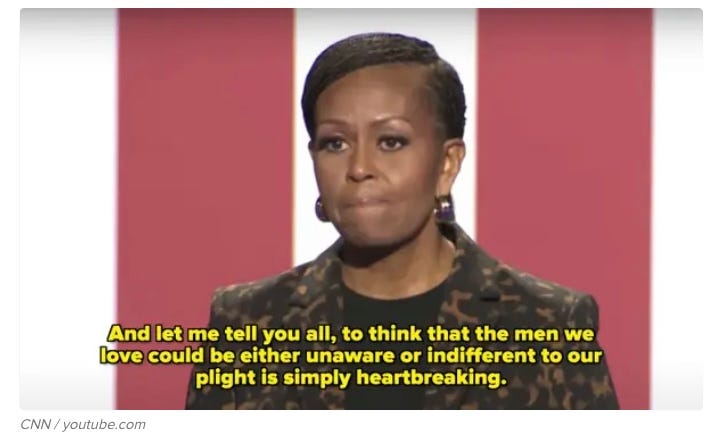

This isn’t the way men have been brought into the struggle for reproductive freedom, however. Instead, their empathy for the suffering of the women and girls in their lives has been emphasized. For example, in Michelle Obama’s impassioned speech:

“To the men who love us...I am asking you from the core of my being to take our lives seriously. Do not put our hands in the lives of politicians — mostly men — who have no clue or do not care about what we as women are going through."

“Please, please, do not hand our fates over to the likes of Trump, who knows nothing about us, who has shown deep contempt for us, because a vote for him is a vote against us, against ourselves, against our worth,”

‘To think that the men that we love can be either unaware or indifferent to our plight is simply heartbreaking. It is a sad statement about our value as women in this world.”

“To the women listening, we have every right to demand that the men in our lives do better by us to make these choices clear to the men that we love our lives are worth more than their anger and disappointment. We are more than baby-making vessels.”

Michelle’s speech wasn’t just a plea to men. It was a speaking-out-loud of the female body that male legislators know so little about yet presume to dictate to (Pregnancy from rape? Tod Aikin, one-time a senate nominee from Missouri: “The female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down.”) No one is a better anger-translator than Michelle Obama. Barack is charming. But Michelle doesn’t hold back on her fury, frustration, and worry. She’s the one who speaks to what so many of us are feeling. In our clenched hearts. Our unbelieving minds. Our anxious bodies. What we are feeling.

Yet the appeal to men, not through the “we” of the economic family unit but through the sympathies of men for the suffering female “others” in their lives, bothered me. I thought a better argument was to respond to the men who saw Trump standing for “the economy” (the big picture, coded as male) while abortion was a “single-issue” that had material consequences for women only.

That was me thinking as a philosopher. Deconstructing and reconstructing and imagining a listener attuned to the voice of reason and argument. Michelle and Kamala, no slouches at argument themselves, took the route of what Carol Gilligan called “an ethics of care,” calling on men’s hearts rather than their minds alone. “Rights” and “justice” and “equality” are crucial ingredients of a humane and moral society, but they are abstractions, Gillian argued, unless they are imagined in the context of actual human attachments.

Abstract notions of “rights” and “personhood” and “choice,” around which the abortion argument was centered for decades, are boundary-protecting. They define a territory for the self and guard against the invasions by and collisions with others. And they are necessary—for women, in particular, whose bodily and emotional boundaries have been ignored or invaded, over and over, by men like Trump who think they can just grab us by the pussy and legislators who think it’s their damn business to decide when we should be permitted to terminate a pregnancy.

But Gilligan reminds us that we are not just atoms always threatening to bump up against each other but bound together in relationship with each other—relationships in which the chief danger is the fracturing of attachment rather then unwanted incursions into the self. “Rights” won’t help us mend those fractures. Only the restoration of connection will. Michelle’s husband shamed men for being sexist, unable to digest the idea of a woman as POTUS. He’s undoubtedly right about lots of men—and women. But shaming doesn’t restore connection; it only elicits defensiveness. Michelle, without giving up her righteous anger, appealed to the attachments that even the most sexist men have with the important women in their lives. I know you love us. And because you do, you must do better by us.

Kamala at the Ellipse: Leadership as Relationship

“Caring requires paying attention, seeing, listening, responding with respect.” (Carol Gilligan)

“Love without real outgoing to the other, reaching to the other, the love remaining with itself - this is called Lucifer." (Martin Buber)

“I will be women’s protector. Whether the women like it or not.” (Donald Trump)

Anderson Cooper’s “Town Hall” with Kamala Harris left me furious for many reasons. Among them was the mocking way the panel of “experts” and several commentators the next day talked about Kamala’s answer to an audience member’s question about what “weaknesses” she brings to the office of presidency.

They mocked her for “word salad.” They mocked her for a politician’s duplicity, coming up with a “weakness” that was actually a way of advertising a strength. A piece the next day mocked her for saying that in trying to solve problems, “she likes to kick the tires, and…doesn’t always have the answers. Given that she is supposed to be casting herself as the solid, practical, serious alternative to Trumpism, such an admission is devastating.”

Devastating?

I heard her answer very differently. I heard her struggling to describe a collaborative style of problem-solving that is precisely why she has so much trouble with the “now tell me in sentence” demands that the media seems to think is the way to “pin down” a person and “hold them to account” for any contradictions, evasions, and changes in their positions. Anderson had been doing that constantly throughout the town hall. Why did your position on fracking change? You once savaged Trump’s idea of building a wall, but the bill you came up with in congress includes a wall; how do you explain that? Etc.

She struggled with such questions, and the reason why—the reason why she struggles with all those “gotcha” questions—is contained in her answer to the “what’s your weakness” question. You had to be listening, though—really listening—instead of impatiently waiting for the bit on which you could pounce.

“I think that I -- perhaps a weakness, some would say, but I actually think it's a strength—is I really do value having a team of very smart people around me who bring to my decision-making process different perspectives. I -- my team will tell you I am constantly saying, let's kick the tire on that. Let's kick the tires on it.

Because, listen, I -- as I mentioned earlier, I started my career as a prosecutor. I was a courtroom prosecutor. I've tried everything from low level offenses to homicides. And I learned at a very early stage of my career and adult life that my actions have a direct impact on real people in a very fundamental way. When I was attorney general of California, I was attorney general of what is the fifth-largest economy in the world, and acutely aware that my words could move markets. So I take my role and responsibility as an elected leader very seriously. And I know the impact it has on so many people I may never meet.

And that is why I engage and bring folks around. So I may not be quick to have the answer as soon as you ask it about a specific policy issue sometimes because I'm going to want to research it. I'm going to want to study it. I'm kind of a nerd sometimes, I confess. And some might call that a weakness, especially if you're, you know, in an interview or just kind of, you know, being asked a certain question and you're just expected to have the right answer right away. But that's how I -- that's how I work.”

Could her answer have been better organized? Sure. She’s just told you, she likes to prepare.

But if you care to actually listen, she’s answering the question.

Let me help you, Anderson:

She knows her words no less than her actions are a serious business. She learned it first as a prosecutor, where the impact of her actions and words on people’s lives was stark. Having a team of people with different perspectives and expertise around her is the way she tries to be responsible. They research, study, “kick the tire” (to see what’s solid and what leaks) and engage with each other. Engage with each other. She considers that a strength. But (and here’s the “weakness” part, Anderson, that apparently you didn’t hear) that makes coming up with the kind of “right answer right away” in interviews (like this one!!) is so hard.

Anderson just saw her as evasive, and was determined to get her to reveal something more headline-y. “I don’t think I've ever heard the former president admit a mistake. A lot of politicians don't,” he began, implicitly accusing her of not answering the question. Then he pressed on: “Is there something you can point to in your life, political life or in your life, in the last four years that you think is a mistake that you have learned from?”

At this point, Kamala was getting angry. Didn’t he hear what she’d just said? After admitting she’d “made many mistakes” she brushed him off: “It's a mistake not to be well-versed on an issue and feel compelled to answer a question.” Anderson didn’t even get the hostility in “compelled to answer a question.”

For her speech at the Ellipse, though, Kamala Harris was able to say it the way she wanted to, and she did it as though she were addressing a person sitting across the table from her rather than a collectivity. She spoke in the first person, avoiding abstractions and soaring words, promising to listen, asking for us to give her a chance. She made “us” feel important, not just for our votes but because we—even if we don’t vote for her—are essential to her figuring out how she can help make our lives better.

I’ll be honest with you, I’m not perfect. I make mistakes. But here’s what I promise you. I will always listen to you, even if you don’t vote for me. I will always tell you the truth, even if it is difficult to hear. I will work every day to build consensus and reach compromise to get things done. And if you give me the chance to fight on your behalf, there is nothing in the world that will stand in my way.

America, we know what Donald Trump has in mind. More chaos, more division, and policies that help those at the very top and hurt everyone else. I offer a different path, and I ask for your vote. And here is my pledge to you. I pledge to seek common ground and common-sense solutions to make your life better.

I am not looking to score political points. I am looking to make progress. I pledge to listen to experts, to those who will be impacted by the decisions I make, and to people who disagree with me. Unlike Donald Trump, I don’t believe people who disagree with me are the enemy. He wants to put them in jail. I’ll give them a seat at the table.

I pledge to you to approach my work with the joy and optimism that comes from making a difference in people’s lives. And I pledge to be a president for all Americans.

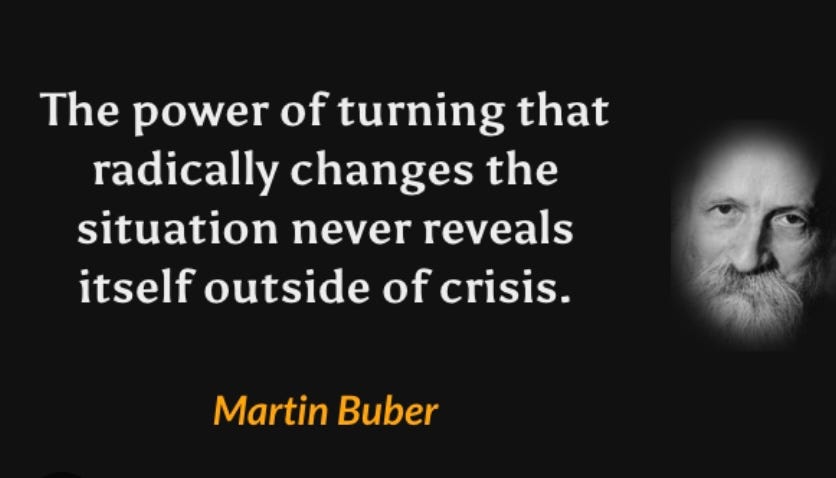

A Final Note of Hope from Martin Buber:

yes, we are in an ellipse state. we are in a dot.dot.dot state; you are so right. Watching Kamala and Michele everything feels suddenly clean and clear; the crowd, the cheers, the hope, the good-hearted faces. It is known to be very hard for traumatized people to bear hope; it so often led to disappointment, and worse -- agony and despair. This election week and the lead-up have put me in a tsunami of anticipatory anxiety and despair. One of my beloved dogs is likely dying. I watch his breathing, I administer fluids daily (renal failure), I try specially cooked fresh meats to stimulate his waning appetite. Will America survive? Can magic or hard work be injected? I know people knocking on doors in swing states. They say 95% of the people, clearly at home, don't answer. I know people writing out postcards. I know people avoiding the topic altogether. I know people canceling newspaper subscriptions. I know people in that "frozen state" we've labeled sitting on couches under blankets endlessly bingeing junk tv. I know that Kamala and Tim and Michele and others will never give up. There is a "wanting to know." There is desire for relief. My "healthy" dog is eating less in solidarity. I try gratitude exercises and it's like scratching at a concrete wall. We're all just so tired and disappointed. Kamala remains a shining, vivid avatar, a place-holder. For some reason I think ahead to Thanksgiving. Will we know anything? Will blood have been shed, uselessly? My family has dwindled; some are far away. I have decided to deliver uncooked turkeys to wherever I can, or hand out meals. After several days of nightmares, I had a dream this morning in which I was suddenly incredibly powerful. There were at least a dozen people in my therapy office. I had more than double-booked! But I turned it around. I turned it into group therapy. People advised each other. I facilitated, organized people into pairs, and calmed down the arrogant, tall man. I used comedy and empathy. I was unstoppable. It was a great dream.

Great writing. The sentences recalling your parents genuinely moved me. Your style and voice elevate political reportage to literature. It's warm and human, visceral and compelling; touching my heart as well as my mind. Such immence talent. I wish I had it.