“At the movies, we want a different kind of truth, something that surprises us and registers with us as funny or accurate or maybe amazing, maybe even amazingly beautiful. We get little things even in mediocre and terrible movies…”

“An actor’s scowl, a small subversive gesture, a dirty remark that someone tosses off with a mock, innocent face, and the world makes a little bit of sense.”

(From Pauline Kael’s writing on movies)

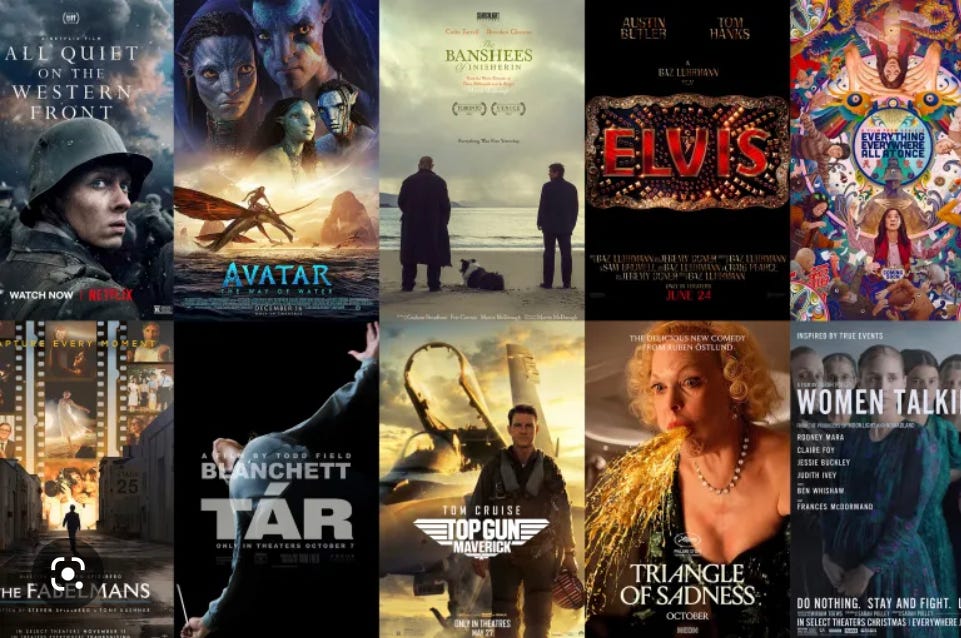

My choice for Best Picture

The Banshees of Inersherin is a beautiful short story of a movie about the oppressiveness, fragility, and indispensable nature of relationships. It’s both very funny and unbearably sad. Like McDonagh’s wonderful In Bruges, it gets its humor from the personalities of the characters as they interact with each other. Sometimes they are dense and mean-spirited and stuck in their ways, like the town’s busy body shop-keeper who demands “news” from her customers. Sometimes they are unexpectedly sharp: “What is he, 12?”says Dominic, the village “gom,” referring to Colm’s “not liking” Pádraic anymore; it’s possibly the best assessment given of Colm’s behavior in the movie. And sometimes the humor comes from the matter-of-fact way the characters behave outrageously. In one scene, Colm—a fiddle-player with artistic aspirations who suddenly wants to be left alone by the friend he had pints and “chatted” with all his life--has just confessed to the village priest that he has had “impure thoughts.” The priest, having been told by Padraic about their breakup, asks Colm if “it’s about him you have the impure thoughts about, is it?:

COLM: Are you joking me?! I mean, are you fecking joking me?!

PRIEST: People do have impure thoughts about men too.

COLM: Do you have impure thoughts about men?

PRIEST: I do not have impure thoughts about men! And how dare you say that about a man of the cloth...!

COLM: Well you started it.

PRIEST: Well you can get out of me confessional right now, so you can, and I’m not forgiving ya any of these things until the next time, so I’m not!

COLM: I’d better not be dying in the meantime then, eh Father, I’ll be pure fucked.

PRIEST: You will be pure fucked! Yes you will be pure fucked!

It’s difficult to convey on paper how hilarious this scene is, with the shouting between the two audible to everyone else in the church, as they get into it in as adolescent a manner as two drunk guys at the local bar. This is a father confessor?? This is the sanctity of the confessional?

But then there's the not-funny-at-all damage people do to each other. Whether they intend it or not, the people on the island always have their personalities, and often their hearts, on display—for better or worse. Often, it’s for worse. Not taking each other seriously enough, people say things without thinking—as we all do—and destructive things come out of it. Dominic tells Padraic that Colm liked it when he blew up at him at the tavern, and this gives Padraic the idea that Colm just needs some “tough love.” Not a good idea. Dominic, who has a crush on Padraic’s sister Siobhan, decides to take a chance and ask her if there’s any hope for him. Not a good idea. She responds as gently as she can, but Dominic is crushed: “Well, there goes that dream.” This kind of thing happens over and over in the film. People don’t take the temperature of relationships and disaster follows: Fingers get chopped off. Lovely little donkey dies. A long-standing friendship is broken. There's a suicide.

It's tempting to see the break-down of the longstanding brotherhood between Pádraic and Colm as a metaphor for the Irish-against-Irish war taking place in the background. (We're reminded of it through conversations about it and the sound of gunfire coming from the mainland) "It was so much better when it was us against the English,” Dominic’s thuggish policeman father says--and I'm sure the resonance of brother-against-brother was intended by McDonagh. But McDonagh himself has said that metaphors weren’t what he was after (nor was caricaturing the Irish, which some Irish critics have complained of. )“The starting point,” McDonagh has said, “was to capture the sadness of a breakup, be it a love breakup or a friendship one.” And that meant being “with the characters,” not using them to convey a message.

In his intimacy with his characters, McDonagh reminds me a bit of Robert Altman, whom Pauline Kael once described as “creating an atmosphere of living interrelationships and doing it so obliquely that the viewer can’t quite believe it…He has abandoned the theatrical convention that movies have generally clung to of introducing characters and putting tags on them.” Another way of saying this: Movies tend to be hyper-economical in communicating what characters are feeling or thinking, and resort to visual codes (for desire, love, confusion, etc.) and recognizable tropes to "inform" us of what the writers and directors want us to think about the characters and events. But McDonagh, besides writing characters who don't fit comfortably into any niche, gives us time--and lots of conversations, and unexpected turns--to get to know them. Poor Pádraic spends a third of the movie wrestling with the possibility that people find him "dull" (it took a lot of directorial confidence to have that conversation repeated over and over in various forms!) But we get to know a lot about him from his hapless obsessing about something that's never occurred to the "happy lad" (as he calls himself) and that cuts him to the quick. But Pádraic, as "nice" as he is, is no angel--and he lacks insight (to put it mildly) about himself and those around him. He plays a cruel trick on one of Colm's new musician friends to get him off the island. He’s then foolish enough to tell Colm about it, just as they might (possibly) be on the verge of mending things between them a bit. The remark sets into motion a series of horrible, shocking events that can't be undone.

I know a lot of viewers found those events to be gratuitously horrible. I didn't. True, they are horrible. And true, they function as a kind of literary device rather than a believable turn of events. But they are, regrettably and painfully, what's needed to shake Pádraic out of his persistent denial, his refusal to believe that Colm means business. Perhaps that's really what Colm wants above everything else, even his music: to be taken seriously as an artist, on an island of "fecking boring men” (as Siobhan, the voice of reason in the film, calls them—though she includes Colm in the lot)

“What do you need from him, Colm? To end all this?” she asks.

COLM: Silence, Siobhan. Just silence.

SIOBHAN: One more silent man on Inisherin, good-oh! Silence it is, so.

[She gets up to go...]

COLM: This isn’t about Inisherin. This is about one boring man leaving another man alone, that’s all.

SIOBHAN: ‘One boring man”! Ye’re all fecking boring! With your piddling grievances over nothing! Ye’re all fecking boring!

I'm not sure what Colm is after, to be honest. But it's really the "evolution" (for want of a better word) of Padraic's response that's the heart of the film. He just can't absorb the possibility that Colm really wants to break up with him, and everything he does--until the beyond awful happens--persists in denying it. Even after Colm throws a finger against his front door, he tries to minimize the finality of the message Colm is sending. He is about to bring the finger over to Colm's house, andSiobhan, rightly, is appalled:

Siobhan: You’ve got to leave him alone now, Padraic! For good!

PADRAIC: Do you think?

SIOBHAN: Do I think?! Yes, I do think! He’s cut his fecking finger off and thrown it at ya!

PADRAIC: Come on, it wasn’t at me.

The man has just shown you he'd rather lose a finger than continue a relationship with you and you're going over to his house? It takes a confrontation with true finality—the death of his beloved donkey, someone he cares deeply about, perhaps more than he cares about Colm--to convince him. And it changes him; he's no longer the "happy lad" he once was. Grim and more sober than we’ve ever seen him, he tells Colm: “Some things, there’s no moving on from.” He’s referring to the war on the mainland, but the words signal that he’s had it, finally. He won’t try anymore; “and I think,” he says, “that’s a good thing.”

For all the local particulars (which some Irish critics have objected to, seeing it as caricatured and demeaning of Ireland) this is a movie that resonates with universal human failings and fragility—and tender impulses, as well. Colm loves his dog and Padraic adores all his animals, particularly Jenny (who one reviewer perfectly described as "the most content and saddest creature on the island"), whose presence comforts him when he’s sad. Siobhan is tender and protective with Padraic, and he is loving with her, hiding the news of Jenny’s death in a letter to her after she’s left the island: “Even now, as I write, little donkey Jenny is looking at me, saying please don’t go, Padraic, we’d miss ya, and nuzzling me, the gilly gooly. Get off, Jenny!” It’s heartbreaking, that letter.

And it comes from McDonagh’s heart, too. I was touched to read, in McDonagh's screenplay, "directions" for the animals: “The donkey looks in thru the open door, confused at all the sadness, then toddles away again,” "The pony looks concerned," etc. As someone who was very disturbed by Jenny's death (I didn't care nearly as much about those bloody stumps of fingers), those directions were confirmation that this was a writer with sensibilities that I share. And perhaps, in the end, that's why I loved this movie. (No lectures from vegans, please!)

Pauline Kael, in her review of McCabe and Mrs. Miller, wondered whether an American audience would accept “a movie as personal as this—not as in ‘personal statement’ but in the sense of giving form to his own feelings, some not quite defined, just barely suggested…movies that don’t resolve all the feelings they touch, that don’t aim at leaving us satisfied, the way that a three-ring circus satisfies?” One of the best of such movies—Aftersun—a debut film by writer director Charlotte Wells, wasn’t even nominated (the lead actor, Paul Mescal, was.) As for the Oscars and Banshees, we’ll see.

Quick Takes on Some of the Others (these are not meant to be full reviews, but literally “takes” that reflect my own idiosyncrasies as much as those of the movies):

The Fabelmans

It’s not Spielberg’s best movie, and it has a happily-ever-after ending (whether or not the events actually happened, which I gather they did) that showed the way that memoirs go astray, when they allow the writer’s memories free range, even if they spoil the tone of the work. But it’s an entertaining movie that Spielberg deserved to make. I loved the details that rang true to assimilated but not quite assimilated Jewish family life (Spielberg—Sammy in the movie—graduated high school in exactly the same year as I did, and although my family never moved from New Jersey to the exotic plains of Phoenix or the coast of California, the push/pull of the “old country” ways and new “American” dreams was familiar to me.) But at the same time, the movie exploded some familiar Jewish movie stereotypes (you can see some of them even in as recent schlock as You People.) That’s the way memoir can do better than fiction. None of us grew up with stock Jewish mothers, and Spielberg especially not. Adventurous rather than anxiety-prone, serving dinner on paper plates on paper tablecloths, dancing without inhibition in front of headlines that clearly reveal her body, the mother in Fabelmans was unlike Molly Goldberg, or Philip Roth’s suffocating fantasy-figures, or the numerous yentas that have appeared in comedies, or the clueless, over-privileged mother in You People. Mitzi Fabelman, with her blonde pixie hair-cut and readiness to goof around, was refreshing. My favorite scene, though, was when Sammy runs through the footage he’s shot of a family camping trip, and discovers—through the piercing eye of the camera, which becomes the truest eye on the world for Spielberg—that something is going on between his mother and “uncle” Benny. Cutting back and forth between the images he discovers and Sammy’s changing expressions, the discovery rivetted the viewer as well as Sam. A master director at work there.

Top Gun: Maverick

Elvis

There’s something magical about the main performances in each—magical in very different ways. I have no idea whether Tom Cruise has had any “work” or not, and I don’t care. He still looks significantly older than the young Maverick, even significantly older than his last Mission Impossible, and I loved that. His neck is ropey, his eyes are tired-looking, and they haven’t used any filters to smooth away lines. To my mind—with due credit to the thrilling flying sequences—it’s what makes the movie more than just a great action flick. I also liked Daniel Craig as James Bond—I prefer male actors when the gloss has worn away--but here the actor, having played the same character earlier (as Craig did not) needs to look older, in order not to betray the sense of Maverick’s history on which so much of the narrative pivots. If Cruise had not looked as frayed at the edges, he would have been just another incarnation of the bigger-than-life hero he has so frequently played.

I generally don’t like Baz Luhrman movies, and I could complain about the things I don’t like. But I’d rather praise Austin Butler, the young actor who plays Elvis. In previous roles and in shots of him (at awards shows, etc.) he looks nothing like Elvis (As far as teen dreamboats from that era go, more like Ricky Nelson.) But Luhrman must have seen the potential in that sensuous, curled lip and sleepy eyes—and Butler apparently did a huge amount of research and worked like hell to embody Elvis—because in the movie, he not only captured the essence of Elvis’s Dionysian appeal but in some scenes looked so much like him (and sounded so much like him) it was breath-taking. I’m glad they didn’t show much of the degeneration of Elvis’s looks, too. This was a movie full of made-up fantasies (e.g. of Elvis not just being influenced—which he was—by Black performers, but being soul-brothers with some of the most famous), and Elvis himself had to be one of them. For me, especially since I wasn’t a big Elvis fan at the time (my mother was), if the movie hadn’t established (or had demolished) his sexual appeal, I probably would have been as bored by it as I was with the real Elvis. I wasn’t bored by this hot young Elvis, though, and it made all the swooning believable.

Tar

Two things the movies never get right: therapy and teaching. So much money spent getting the details of a 16th century castle exactly, and do they even visit a classroom in their research? I can’t think of a single campus-based movie that didn’t turn teachers into beloved imparters of wisdom (Dead Poets Society) or tyrants (Paper Chase) or both (Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.) Those are older movies, but it hasn’t gotten any better.

The first half-hour of Tar, in which she’s interviewed, was chillingly accurate—so accurate I thought it was a parody. I’d had dinner with those people at philosophy conferences; I’d watched them preen in seminars. When her time with an African tribe was referenced, I hooted. Perfect detail.

But then they took her into a classroom. Now, I know what it’s like to have a class taken over by the culture/language/race/gender police. It’s happened to me, and it’s pretty gruesome. But that young man who had no interest in Bach because he was a heterosexual was worse than a parody; he was a cartoon who could have been written to specification by Ron DeSantis. Did Todd Field want to feed red meat to the Right, or what? And Lydia’s grandstanding bullying was so over-the-top the movie lost me right then and there. I was a philosophy student, and a female one; I’ve been bullied by masters. But none of them would have been so stupid as to humiliate me so cruelly as Tar does that boy. I guess they had to make him insufferably P.C. in order to get her to be that awful to him.

But, as my friend Laurel Brett noted, Cate “sure does justice to a pair of trousers.”

Women Talking: Please see my stack post, “Goodbye, Postfeminism”

Everything, Everywhere All at Once; Please see my stack post “Everywhere”

Triangle of Sadness

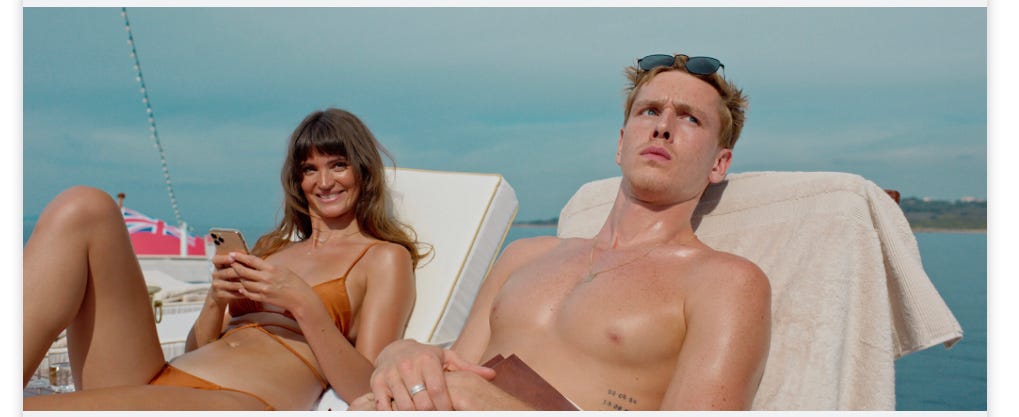

The first two sections of the movie—in the first, male models audition and we’re introduced to Carl, a not very successful model who just can’t relax the “triangle of sadness” in his forehead; in the second, he and YaYa, a much more successful female model--have dinner and spar over who picks up the check—brilliantly capture the weird (and for Carl, sad) , superficiality of the world of “influencers,” whose lives revolve around posing for Instagram and taking advantage of the free goodies that come with that “job.” One of those goodies is a luxury cruise, which the third section of the movie puts Carl and YaYa on, and the film shifts focus from their “culture” to the far more repellant imperiousness of the rich bourgeoisie who actually paid for their cruise. There’s an older couple who have made their fortunes “defending democracy all over the world” (he’s a manufacturer of grenades and other weaponry.) A rich Russians who literally “sells shit.” A single woman who forces the crew, who have been instructed to cater to the guests’ every whim, to go swimming. And so on. They are all so grotesque that Carl and YaYa become quite sympathetic characters. A lot of it is very funny. But then the projectile vomiting began (there’s a storm that makes everyone seasick)…and the toilets overflow with diarrhea and the woman who forced the crew to swim goes sliding across the bathroom floor in her own vomit and feces….and I had to see what was happening in some other part of my house. Yes, the whole disgusting spectacle was farce. But I didn’t appreciate being made nauseous myself by my evening entertainment. In the last section, several of them—including Yaya and Carl—are stranded on an island, and the working class gets its revenge, in the person of the toilet manager who, by virtue of her skills at catching fish and making fires, becomes the new “captain” of the island. It was pretty delicious, I will admit, to see her become the dominatrix of pretty-boy Carl. But in general, I’m not a fan of “messages” or having political ideas force-fed to me in movies. And at some point Triange of Sadness started to feel too instructive. I did unreservedly love the first two sections, though.

Avatar: The Way of Water

This one was a family affair, the first time since the pandemic that all three of us—my husband, my daughter Cassie (age 24) and me—went to a movie theatre together. So I’ll post a family review that I put up on Facebook the morning after we saw the movie:

Mom: Needed about a half hour of non-stop fighting cut. Story line and “message” corny. Visually dazzling but after awhile I felt I was being forced to be dazzled. I was also moved by various scenes and relationships, but again, felt coerced into it. Bored by first half (Cassie caught me dozing at one point) and the anti-aging serum they killed the Tulkuns for reminded me, absurdly, of the Prevagen commercial, in which they claim the “secret ingredient” comes from jellyfish. I did get swept up eventually. I’m a total sucker for an animal rescuer, and the enormous, misunderstood Payakan was especially touching.

Cassie: NO WAY SHOULD ANYTHING BE CUT, MOM! (And then she proceeded to connect every possible dot between the first Avatar and this one to show why every bit was necessary.)

Husband Edward: “I’ve never seen anything like that!” (We all had seen first Avatar, but it didn’t make as big an impression on him as this one.) But know that this is a guy who when left to his own devices with the remote watches “Columbo” and “Perry Mason” (the Raymond Burr one.) He was like a little kid with this movie.

Speaking of little kids: We all loved Tuk.

All Quiet on the Western Front

Brutal, horrifying, sad. War.

That’s all for now. My favorite film of the year, by the way, was Aftersun. But I’ll talk about that another time.

Typo/ edits: headlines should be headlights in Fabelmans review; ELVIS header is misplaced.

Damn you're good at movie reviews! Thank you Susan!