Coupledom Deconstructed: “Maestro,” “Anatomy of a Fall,” “Succession,” “The Morning Show,” “The Diplomat,” and…me.

Real life is neither a rom-com or a commercial, and film and tv is finally getting real.

Couples say the most horrible things to each other.

This past year, we’ve seen some brutal fights between couples. The most shocking was between Siobhan Roy and Tom Wambsgans in the “Tailgate Party” episode of Succession. The immediate cause was what was, perhaps, a misunderstanding: what Siobhan described as a “tactical play”—her undercutting Tom as she schmoozed with Matsson and others major players at the party—Tom saw as a betrayal. They might have sorted it out, but Tom was exhausted and Siobhan was smarting from his gift of a scorpion broach earlier that day (Tom: “That was a friendly thing”; Siobhan: “Oh, yeah. Sure. Real friendly.”) She should have just let him go to sleep. Instead, the conversation escalated into mutual evisceration.

S: Uh, I'm a scorpion. You're a hyena. You're a... You're a street rat. Actually, no. You're a fսcking snake. "Here's a dead snake to wear as a necktie, Tom. Why aren't you laughing?"

T: I wonder if we shouldn't clear the air. Yeah? I think that you can be a very selfish person, and I think you find it very hard to think about me.

S: What the fսck? And I think you shouldn't have even married me, actually. What the actual fսck? You proposed to me. You proposed to me at my lowest fսcking ebb. My dad was dying. What was I supposed to say? Perhaps, "No"? I didn't want to hurt your feelings.

T: Oh, thanks! Thanks for that! Yeah, you really kept me safe while you ran off to fսck the phone book.

S: Oh, fսck off. You're a hick. Conservative hick. You hid it because you were so scared of how fսckin' awful you are. You were only with me to get to power. Well, you got it now, Tom. You've got it! You're fսcking me for my DNA. You were fսcking me for a fսcking ladder because your whole family is striving and parochial.

T: That's not... That's not a fair characterization.

S: Oh, no? Well, your mom loves me more than she loves you because she's cracked.

[Tom then accuses Siobhan of being willing to have him go to prison for the family and Siobhan insists that he offered to go.]

S: You offered to go to jail, Tom! You offered because you're servile! You're just...

T: You're servile! You are incapable of thinking about anybody other than yourself 'cause your sense of who you are, Shiv, is that fսckin' thin!

S: Oh, yeah? Yeah. You read that in a book, Tom? You're too fսckin' transparent to find in a book! You're pathetic. You're pathetic. You're a masochist, and you can't even take it.

Tom: I think you are incapable of love. And I think you are maybe not a good person to have children!

[Siobhan’s expression changes with that comment. In fact, she is pregnant. And the comment hits a live nerve, as her mother had said the same thing to her before, in season 3: “Some people are not meant to be mothers”]

S: Well, that's not very nice to say, is it?

Tom: I'm sorry. I'm sorry. But you... You... You have hurt me more than you can possibly imagine.

S: And you, you took away the last six months I could've had with my dad.

T: No.

S: Yes. You sucked up to him, and you cut me out!

T: It's not my fault that you didn't get his approval. I have given you endless approval, and it doesn't fill you up because you're broken.

S: I don't like you. I don't... I don't even care about you. I don't care. Have we cleared the air, huh? Feel good now?

T: Yeah. Great. Tip-top.

S: Uh-huh. You don't deserve me. And you never did. And everything came out of that.

Almost without exception, viewers and critics declared that this fight “disemboweled” the marriage, that the comment about Siobhan’s inadequacy to be a mother, in particularly, was “fatal” to the relationship, and that “they will not come back from this.”

And then there was Bradley’s (Reese Witherspoon) total meltdown after her mother’s death, in the “Love Island” episode of The Morning Show. During the pandemic, Bradley and Laura had been living together in Laura’s “cozy” Montana villa, doing “The Morning Show” together from there. Things are fine until Bradley’s mother, thousands of miles away, dies of COVID and Bradley becomes so unhinged that she projects all her own guilt onto her Laura, in a fight that escalates into sheer mutual cruelty:

Bradley: You hated everything she [her mother] stood for. And I stopped talking to her because I could feel it every time… You know what I fսcking think? I think you like to dress me up, a-and... and parade me around for your fancy fսcking New York friends. I'm like your little white trash pet… I think you don't even really like me. I think that it makes you feel better about yourself, because you're actually an elitist snob who hides out at the edge of the world so she doesn't have to deal... fսck you. ...with real people. fսck you. You must be so filled with spite, it just corrodes your insides. Think you're happy when people like my mom die, because they had... they get COVID 'cause they're uneducated, or they're hicks, or they're just not as fսcking smart as you.

Laura: You know what I think? I think there's a little part of you that's actually relieved. You're glad she's gone. You just don't have the guts to admit it, Bradley. And you need to grow the fսck up. You need to grow up and stop blaming me for all your shit. You can't just dump all your stuff on me! fսcking be proactive and stop rewriting some sort of history, Bradley. Your mother was a piece of shit. You're the first person to tell everyone about it.

This was almost as searing a couple fight as Siobhan and Tom’s spewing poison on each other on the balcony—and some critics felt it went over the top into pure soap drama.

I don’t agree.

Right after the “Tailparty” episode, I posted a screenshot of a “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” poster. I was thinking of all the times when couples, who are always bound together by shitty reasons as well (if they are lucky) for good ones, ”snap” (as Martha puts it in Albee’s play) and all the bad stuff comes pouring out. The resentments, the compromises, the hurts, the humiliations, the not-so-clean motives for staying together, the secrets that are fine so long as they stay unexpressed but painfully wounding when they are given voice.

It’s not usually because the relationships are doomed. It’s because intimacy is both precious and risky (that’s why so many people try to avoid it.) It’s precisely when people who know each other intimately let loose, that fights become volcanic, un-moored from fact, oblivious to consequences. Paradoxically (at the same time as it makes perfect sense) it’s those with whom we feel the safest, the most known-by, the most comfortable with, that we allow ourselves to go over-the-top hurtful with.

So many viewer’s reactions (“it’s over between them now; they won’t come back from this”) to the Tom and Siobhan scene and the Bradley/Laura scene seem to come from an “I would never behave like that” place (no?) or the conclusion that ”the real truth is coming out now.” But what is “the real truth” of relationships? That’s a question that the award-winning Anatomy of a Fall raises, and I think that Sandra, in that film, describes those excruciating moments of attack and counter-attack more accurately.

For those who haven’t seen the film, the “thriller” part of it is the question of whether Samuel, whose dead, bloody body has been discovered (by their son, visually-impaired and deeply perceptive Daniel) at the bottom of their three-story mountain cabin, has fallen by accident or been murdered by his wife, Sandra. In court, the prosecution plays a tape that Samuel had made, unknown to Sandra, recording a blistering fight between the couple. In it, Samuel, frustrated by his inability to write, blames Sandra for leaving him with responsibilities for Daniel, while she (Germanic, stoic, with apparently with none of the blocks that torment the more volatile Samuel) pursues her own writing. It starts as a verbal argument, but eventually turns physical. Wine classes are broken, Sandra hits Samuel, and hell breaks loose, during which either Sandra slaps Samuel repeatedly or he slaps himself (the court only has the audio.)

The courtroom is shaken by the apparent violence of it. And Sandra’s lawyer is appalled that she hadn’t told him about the fight. But for Sandra (although her husband is French, she is the true post-structuralist of the two) “that recording is not reality. If you take an extreme moment in life, an emotional peak, and focus on it, it crushes reality. It may seem like irrefutable proof, but it actually warps everything. That is not reality. It’s our voices, but it’s not who we are.”

When Samuel’s therapist testifies about Samuel’s view of Sandra as “castrating” and self-absorbed, Sandra responds to him with what to my mind, is the truth of most fights between couples, particularly if the relationship is long-standing. They are rarely definitive; rarely “fatal,” but a snapshot in (painful) time. If we believe Sandra’s account, by the next day things were back to “normal” between them, their resentments and even violent impulses folded into ongoing life. (Unfortunately, Samuel’s is cut short.)

These comments of Sandra’s are, in a sense, what Anatomy of a Fall is all about. When long-standing, intimate relationships are concerned, there are no completely explanatory assessments or conclusions. Perhaps that’s why the film never does provide explicit detail as to what happened to Samuel. Between Sandra and Samuel—and between Sandra and Daniel—feelings flow back and forth, sometimes things are very clear, sometimes obscure. It’s fascinating to watch as it all unfolds. Just don’t try to nail it all down.

Perhaps you’ve never had a fight like those I’ve discussed here. I’m not talking about the ongoing or periodic abuse of one partner by another (that’s something else entirely); I’m taking about eruptions of mutual but usually suppressed anger. Eruptions when the most awful stuff got said. When you suddenly realized how much you’ve hurt/hate/misused/been misused by the person you’ve married, or live with, or even just been best friends with. When you both behaved in the most contemptible ways, when every hurt became a desire to hurt. I know I have. And sometimes there is no coming back. And sometimes there is.

“How can someone live like that?”

I’ve frequently been surprised at Facebook comments that reveal how narrow and judgmental many people’s parameters are concerning what constitutes a successful relationship. It happened a lot during the first season of The Diplomat. Kate’s diplomatic husband Hal is an ego-driven, totally undependable partner. He lies to Kate, he has ambitions he hides from her, and his seeming self-effacement is clearly a performance—and an unsustainable one. He seizes every opportunity to advance his own ambitions, and it’s pretty clear by the end of the season that despite telling Kate how much “fun” he’s having “being a back-up singer,” he’s got his eye on the position of Secretary of State. I don’t know anyone who didn’t want Kate to dump him and get it on with Austin Dennison (David Gyasi), the hot Foreign Secretary who can “barely breathe” when he’s in a room with her.

So why is she still with Hal? There are probably a dozen reasons, from the comfort of being with someone you can trust to sniff your skanky underarms and still want to have sex with you to the fact that she is still, on occasion, dazzled by his political savvy. There’s a ton of backstory we don’t have, too, about the fifteen years they’ve been married before the events of the show unfold. (We don’t know, for example, whether not having children was a choice or something else.) We don’t know what Kate’s childhood was like. We don’t know what she was doing when they met. We don’t know what kind of crises they helped each other deal with.

There’s a lot we don’t know. What we do know is that they’ve been together for fifteen years. And for the creator and show runner of the series Debra Cahn, that’s the most salient fact:

“It’s hard to keep a relationship going over time, be it a marriage or a military alliance. We change, we grow, the world changes, and yet we want these relationships to last. [The Diplomat] is a show about a bunch of good people doing their best to keep their partnerships alive, while trying not to kill each other.”

In The Diplomatic we get a relationship in which, like real life, longtime partners stay together despite each other’s worst qualities, for reasons that are as various, mysterious, and completely understandable as there are partnerships. Hal drives me crazy. He drives Kate crazy too. Yet she stays with him. That makes their relationship a source of dramatic tension as well as a bit of realism in what is otherwise kind of a fairy-tale.

The Diplomat is a terrific show, but a total fiction. In real life, people stay with each other despite far more formidable obstacles:

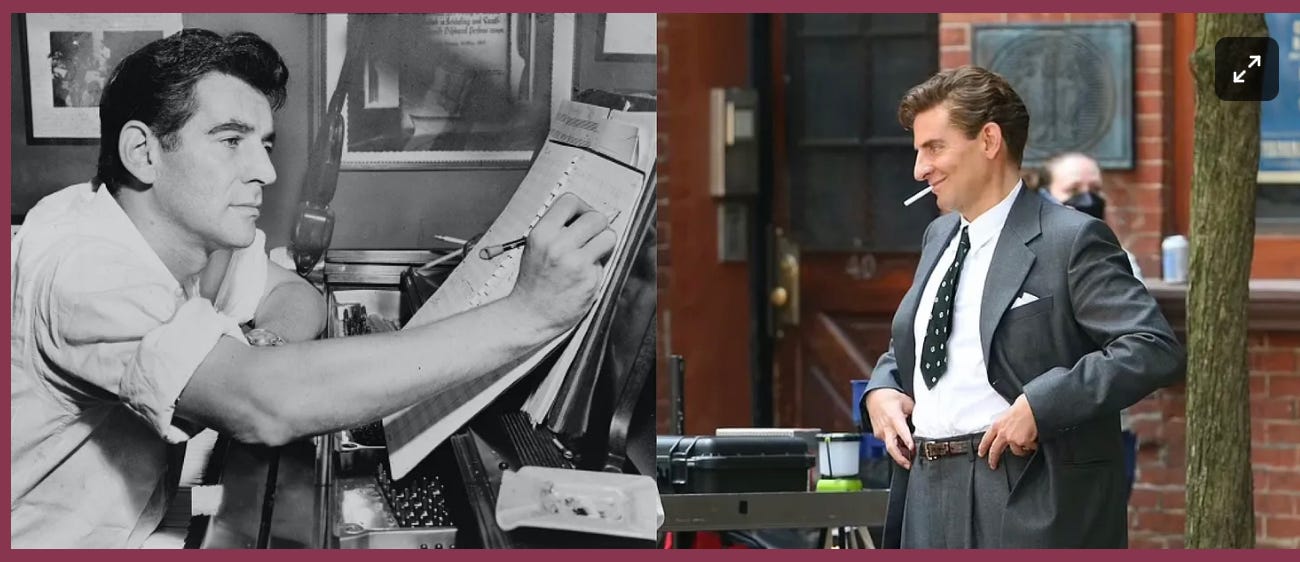

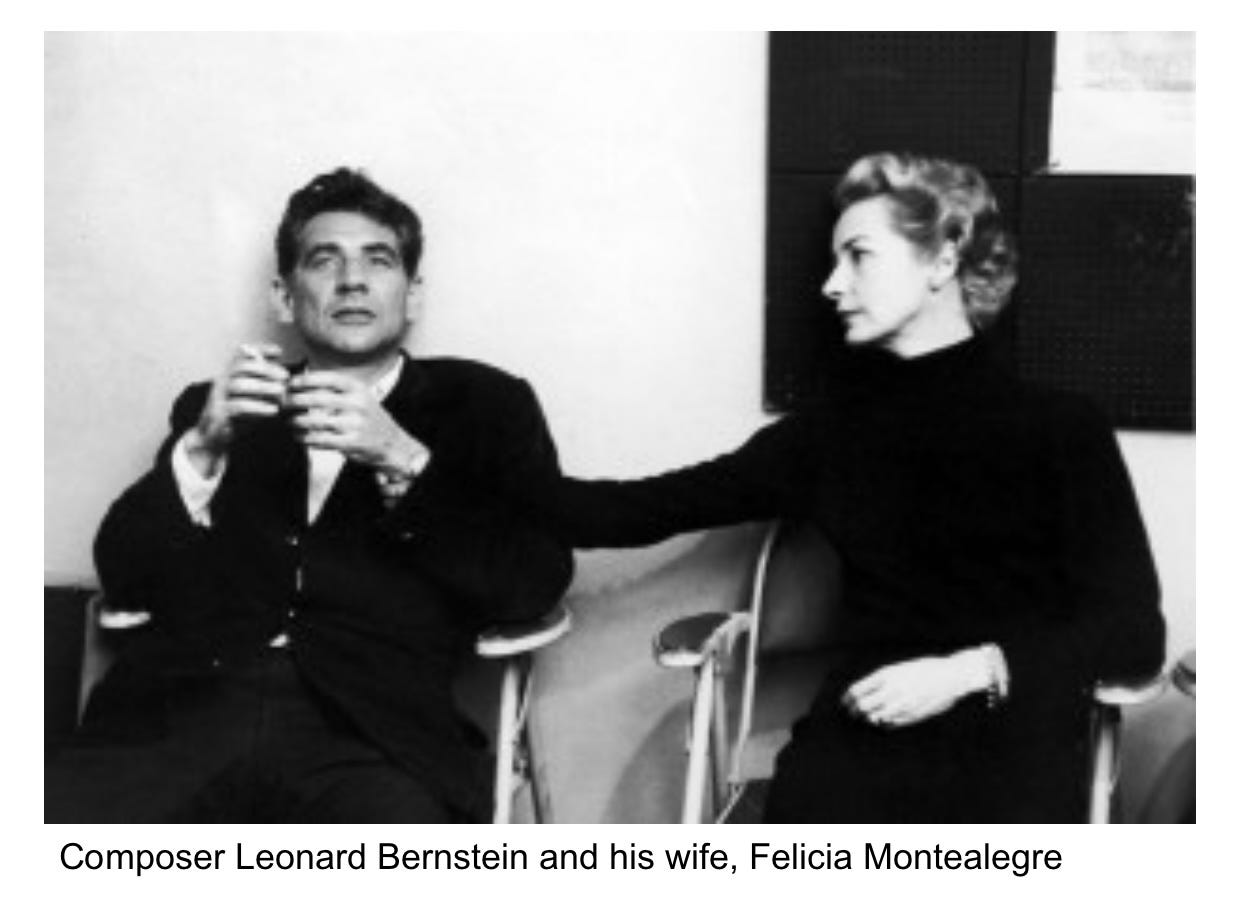

One of the daunting realities looming over "Maestro" is Leonard Bernstein's sexuality. The musician had everything from casual trysts to deeply meaningful love affairs with both men and women…

Montealegre knew of Bernstein's homosexual affairs before marrying him and initially accepted him for who he was. She was convinced that, because he loved both men and women, Bernstein could discreetly give into his physical desire for men without sacrificing a marriage based on a deeper connection.

In a now-famous letter unearthed from the Bernstein archives, Montealegre revealed her progressive mindset on the topic: "You are a homosexual and may never change ... if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? ... let's try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession, please!"

Montealegre, from the moment she met Bernstein, had felt that they were “destined to share a life." And they did. Having a “progressive mindset,” however, didn’t conquer the emotional realities Felicia would encounter. As their daughter Jamie Bernstein describes it, Felicia “knew the challenges; she knew she was marrying a tsunami—and a gay one at that. She believed she could handle it all, that she wouldn’t sacrifice herself “on the L.B. altar.” And she did handle it, for a long time. But then there was Tommy Cothran. And a mastectomy. And loneliness.” And one night, when Lenny proposes that he spend the summer with Tommy, it erupts:

[F]or Alexander’s big twenty-first birthday party up in Fairfield, Daddy had arranged for a small plane to fly over the house trailing a banner that said “Happy Birthday Alexander!” But when the plane made its appearance overhead, Alexander was indoors smoking pot with some friends; he missed the flyover. Daddy flew into an uncharacteristic rage. Mummy didn’t join the party until late in the day. She emerged at five p.m. with big sunglasses on; that meant she’d been crying. Later, we pieced it all together. Julia reported that she’d heard the two of them arguing the night before and that La Señora was using her big, scary theater voice. Alexander found Daddy’s watch in the guest room the next morning. It emerged that our father had decided not to go up to Martha’s Vineyard with the rest of the family the following month. It further emerged that he was planning instead to spend the month in Northern California with Tommy Cothran. And Mummy had apparently told him that if he did that, he would not be welcome to come back to the Dakota in the fall. And Daddy had said okay. Alexander said, “He’s coming out of the closet ass-first.” For the next several weeks, Mummy was alternately furious or bleakly exhausted.

In Maestro (which really should have been called “Lenny and Felicia”) Bradley Cooper imagines the argument. Here, he provides a commentary on the scene:

“If you’re not careful, you’re going to die a lonely old queen.”

Felicia really did say that—although at a family dinner, not in a private argument with Leonard. She felt betrayed. This time she was being asked, not just to share but possibly to be replaced. And feeling irreplaceable was central to what compensated for not only accepting his sexual affairs, but subordinating her own career to the care and protection of Lenny. It was a cut so deep that it released what is always the most deadly kind of strike: one aimed at the trembling, raw center of the fears the other person has for himself. Jamie again:

…[The marriage] had certainly been difficult for both of them. On the one hand, Lenny needed Felicia’s steadying influence: needed a Mrs. Maestro, as well as someone to tell him not to wear the flocked orange sweater. On the other hand, Lenny needed his other life; he wasn’t entirely alive without it, and in the end he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, suppress it. Felicia found herself forced into the role of an angry scold—and that wasn’t fun for either one of them….

The thing of it was, they’d really loved each other. Maybe that explains why Mummy put up with Daddy’s stifling attentions as he stretched himself out next to her on her sickbed. And maybe that explains why, in Munich four years later, LB required his scotch, his multicolored pills, and an entourage filling an entire swimming pool at the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten…

The thing of it was, they’d really loved each other. In relationships, it’s not always the most vibrating connections, although they may be fulfilling and exciting, that are the most essential to the self. Some people need a sturdy guardrail if they are to thrive; others may need to heal repressed childhoods with a partner who is more welcoming of emotional expression. But unfortunately (and sometimes tragically) what is essential, while necessary, may not be sufficient. So there is struggle. Our cultural scripts—the rom-coms, the commercials, the “how to’s” of happiness—rarely include love stories that acknowledge that, as Maestro did.

[There’s another section in this post. But if after reading, you want more on Maestro, see my previous post:

“Any Questions?”

The phrase, which is repeated twice in Maestro—once by Felicia, during a lunch with her sister-in-law in which she reveals some of her loneliness, and then again at the end of the film, by Bernstein, at the conclusion of the interview that opens and closes the film—is something of an insider “joke,” but with a serious meaning for the film, which also opens with a quote from Bernstein that the purpose of art is to pose questions.

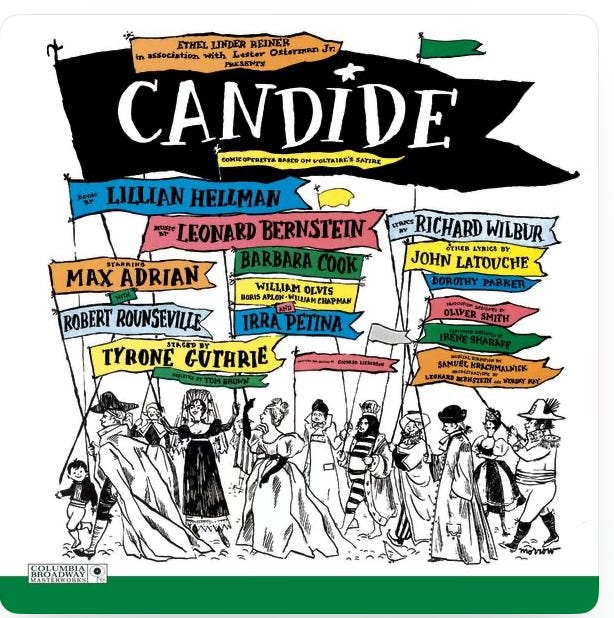

“Any Questions?” Is a line from one of the best-known songs in Bernstein’s Candide. Listen (click on the link and you’ll hear it) as Pangloss defends marriage in “this best of all possible worlds.” One of the topics of Pangloss’s Socratic back-and-forth is marriage.

PANGLOSS:

Any questions?

Ask without fear

I've all the answers here

CUNEGONDE:

Dear master, I am sure you're right

That married life is splendid

But why do married people fight?

I cannot comprehend it

The song is satirical. But Cooper really does mean to pose the question. In an interview with Stephen Spielberg, he said that his biggest hopes for Maestro were that “Bernstein and Mahler will be Spotified and people will rethink what marriage is.”

I didn’t need the film for that. But the film—and the warmth of the community of writers I’ve discovered on Substack—has emboldened me to reveal why not. Not for the sake of personal revelation. But because these kinds of stories need to be told. And I have one.

I’ve been in a marriage that, except for a brief period when we started dating and another when we tried (without success) to get pregnant, my husband and I haven’t been sexual partners. We’ve been together for nearly fifty years. We love each other deeply and dearly—which doesn’t mean it hasn’t been difficult. And hard for other people to understand. I’ve quit two therapists because they kept urging me to leave Edward for a more integrated life.

At one point, wanting to explore the issues raised by a life lived not according to cultural script but unwilling to invite readers into my (and my husband’s) private life, I wanted to write a novel based on it. I wrote up a mini-proposal for my agent, including a brief scene in which “Sarah” attends her consciousness-raising session and talks about the relationship.

Here’s what I sent to my agent:

As Americans in the second half of the twentieth century are taught, sex is the essence of happiness and the fuel that makes a relationship run. If a couple can't get it together sexually, they need to work on it; if they can't fix it, they need to move on. Of course, we allow that long-standing relationships "wind down"-but even so are encouraged, by the sex experts, the drug companies, and all our models of successful, thriving people, that we can, and should, keep our sex lives going as long as we can-into the seventies, eighties, nineties. So, it's okay if we have to fight to "keep it alive" into old age. But the notion that a young, healthy couple would begin—and remain—together, decade after decade, despite the failure of sexual connection, simply has no place in our cultural script. That "script" extends to contemporary fiction, which prides itself on breaking with convention but which has not yet challenged what is perhaps the most pervasive, least examined of contemporary conventions, both cultural and literary: sexuality as the thermometer, barometer, register of romantic love.

My novel begins with the story of Sarah and Douglas, who meet in the early nineteen seventies and, despite the fact that they are strongly drawn to each other, are unable to "make it work" sexually. Why not is one of the questions the novel explores, but doesn't answer definitively, preferring to let it remain the complex human mystery that I believe it to be. So, we learn about those features of their personalities [Sarah: volatile and impulsive; Douglas: measured and reserved,] their family histories, their different ethnic [Jewish;WASP] and cultural sensibilities (Sarah,born right after the war, is a quintessential child of the sixties; Douglas, just eight years older, was raised in a pre-war culture of good girls and bad girls] that contribute to their sexual disconnect. But also, some defining events from their first dates are dramatized—moments that set them on a particular path, a path that perhaps could have been different had a certain gesture not been made, certain words not spoken.

We also see that what makes sexuality difficult for them as a couple is at the same time what keeps them together. Although it is a constant struggle (Sarah, in particular, finds the failure of sex between.them heartbreaking), what they most need from a life partner is ultimately exactly what they give each other, and what makes it possible for them to form a family together. That, however, is something that only emerges over the course of the novel.

The novel tries to “answer” (that is, provide one illustration “answering”) the conventional response to sexless marriages: “How can they live like that?” In one scene, Sarah confides in her consciousness-raising group:

It was a warm midsummer night, and the meeting was at Sarah's ex-roomate Sherry's house, where Sarah used to live before she moved in with Douglas. All seven of them were seated on the floor around Sherry's coffee table, dipping pieces of pita bread in humus and Baba Ghanouj. It had been an especially relaxed meeting--even Tonya was mellow-and Sarah impulsively confided in the group about her sexless life. "I know I should leave, but I love him!" The phrase, she knew, was inadequate to describe her feelings. Particular details would have been better. The calming effect his sheer physical presence had on her. His sudden, unexpected goofiness. The peace she felt, watching him grade his students' papers. She sometimes imagined that devotion, that attentiveness, lavished on a child, and alongside that imagining, his rejection of her body (for that’s how Sarah then saw it) seemed more like a mystery than a negation, part of some cosmic balancing, whose logic she didn't yet understand.

But this group wasn't especially literary, and most of them scorned anything that smacked of mystical thinking. They were devoted, instead, to the "politics" of relationships. They had been pleased when Sarah had gotten her first husband—“that fascist economist"—out of her life, and couldn't believe that she had seemingly traded Simon for such a "withholding" new partner.

"How can you stay with a man who doesn't make love to you? How can you live like that?" That was Tonya, her voice vibrating with aggression masking as concern. But Tonya, it turned out, wasn't the only one who was amazed, even horrified by her situation. They all were, actually, even her ex-roommate Sherry, who by now was a practicing therapist and knew her better than any other woman in theroom. Sherry liked Douglas—found him intelligent, droll, and sympathetic—but she couldn't imagine a "healthy" man rejecting Sarah. She also disliked Tonya—it was a strong bond between her and Sarah--and before Sarah had a chance to respond to Tonya's questions, interceded.

"I'm not comfortable with that way of putting it, Tonya" she said in measured tones. Her Australian accent made the therapy-speak sound natural. Sherry had a round, elf-like face, with strikingly blue eyes, turned up nose, and a beautiful complexion; her dark brown hair was cut very short, the way Joan Baez was now wearing it. Everything about her suited her, Sarah thought, precisely expressed who she was. And she looked just the kind of therapist you'd want to have, not at all like the string of cold professionals she'd seen when she was going through that agoraphobic hell.

"But Sarah, sweetie, I am concerned. I can't help thinking there's some sort of childhood trauma there. Or could he be homosexual, and in denial?"

Tonya quickly shot back. "Well, I'm not comfortable having this discussion be about Douglas. This isn't a place for us to solve their problems, but our own. We shouldn’t be analyzing Douglas, but helping Sarah to claim her own power in the relationship." There it was, Sarah thought. It had taken, what, maybe five minutes?

Sherry: "I just don't think being judgmental is the way to help Sarah."

Tonya: "I wasn't being judgmental; I was being straight with her. Why do we always have to tip-toe around each other? Are we such frail flowers that we can't take a little criticism?"

Sarah's mental storehouse of images of herself definitely did not include frail flower. Anxious, yes, but frail, no. She'd had it with Tonya and her Dedicated Politico persona. But she didn't accept Sherry's "repressed homosexuality" or "childhood trauma" theories, either. She saw her sexual problems with Douglas all as her failure: she was too needy, too overwhelming, too intense, too much, just too, too much. And that was something she would never say in this group. She knew that if she did, most of them would swarm all over her, lavishing her with compliments on her body, her beauty, her sensuality, reminding her of her accomplishments, hugging her and looking deep into her eyes as if their love and reassurances could simply exorcise Sarah's shame. The others-including Tonya-would be disgusted at her "attitude of self denigration." So instead of saying what she really felt, she said something that was merely true.

"You know, there's something a little weird about all this emphasis on sex. Sure, I'm hurt by what's going on and don't understand it. But don't you guys remember all the conversations we've had in here about men not listening to us when we talk? That glazed look in their eyes, the boob-staring? The distracted conversational “uh, huhs” and the professors who wouldn't call on us when our hands were up for ten minutes, who only seemed to be able to see male hands in the air? The lefties who always hog the microphones at the demonstrations? Well Douglas is nothing like that. Nothing. He looks at me when I'm saying something. He listens to me. He takes my ideas seriously.Are you guys saying I should just throw that away because we're having sexual problems?"

That shut Tonya up. Everyone had an anecdote she wanted to tell about being intellectually dismissed orignored by a man, and the focus quickly shifted away from Sarah and Douglas.

Sarah, hurt and frustrated by Douglas's lack of sexual desire for her, embarks on a passionate affair with another graduate student.The affair culminates in a pregnancy, and Sarah is forced to choose between the two men. She chooses Douglas. The irony (and pathos) of Sarah's choice is that, pregnant, she realizes Douglas is the only one of the two men who she can imagine actually raising a child with. Having seen this, she ends the affair with the biological father and terminates the pregnancy.

The proposal went on, but I‘ll stop there. My agent wasn’t thrilled with the idea—he liked me doing cultural criticism, those books of mine were doing well, and he couldn’t exactly see that this was cultural criticism, just of a different sort. Undeterred, I sat in on a fiction-writing course and wound up writing some hundred pages. But then, Anne Boleyn entered my life and I abandoned the novel.

Any questions?

This was more than I can really process reading in an app on my phone but I loved it-- And admire all the thinking and feeling that went into it. I had forgotten the Tom and Shiv scene and haven’t seen the Morning Show but Maestro is fresh in my mind and those fights felt real and earned. Yes, marriage is complex! And then people change so much more than they expect. What’s tolerable or intolerable changes too. Thx for making me reflect on all this! (You should write that novel and serialize it here!)

I’ll skip the usual business of “I wish more cultural and social critics were this good” and get to a bit of my own dishy sociology inspired by what you wrote.

As awful as couples can be to each other, it’s amazing to me how unhelpful the advice of friends can be. And while I generally have respect for the therapy profession, it’s an abstract respect. Actual therapists are capable of poor judgement just like other humans are.