I feel protective of Molly Jong-Fast. On television Molly is such a contrast to the smooth, groomed-for-tv broadcasters she appears with. Her nasal, whiny voice hasn’t been trained out of its east-coast, Jewish inflections. Her eyes never look like they’ve just spent an hour getting bolded by the make-up artists. She’s unfailingly generous with others on the MSNBC panels, even when they don’t deserve it. Her insights are often right on but never delivered as though she thinks she’s the smartest voice in the room—which she sometimes is.

I feel protective of her mother, too. Erica Jong was among the most famous feminist authors of my generation. In “Fear of Flying,” she not only dared to be as erotically unabashed and politically incorrect as the male writers of that generation but as comedic, freewheeling, and self-indulgent as they were. And she was brainy: new readers may be surprised to find the sexy spice of the book peppered with references to philosophy, psychology, literature. The book was not just a major letting loose (and fast and loose, too, with the private lives of barely disguised husbands and lovers) but it was also very, very smart. And still a pretty great read.

Why do I feel protective of these women I’ve never met and who are unlikely to read what I’m writing about them? At 46, Molly, could be my daughter, and watching the TV version of her—endearingly modest, unpolished—brings out the same kind of maternal feelings I felt toward my graduate students. I always tried to be supportive of them, always offered any criticisms with tenderness and empathy. As for her mother Erica, who at 83 is a few years older than I but belongs to the same generation of the “Women’s Liberation Movement” (as it was called in those days), I come to any discussion of her both with identification as an older woman and my long-simmering anger at how the intellectually ground-breaking, culture-transforming, vibrant and politically necessary work of the (so-called) “second-wave” has been disappeared. And not just by male-written history, but by younger generations of feminist writers and teachers.

I’ll write more about that cultural disappearance in another stack.

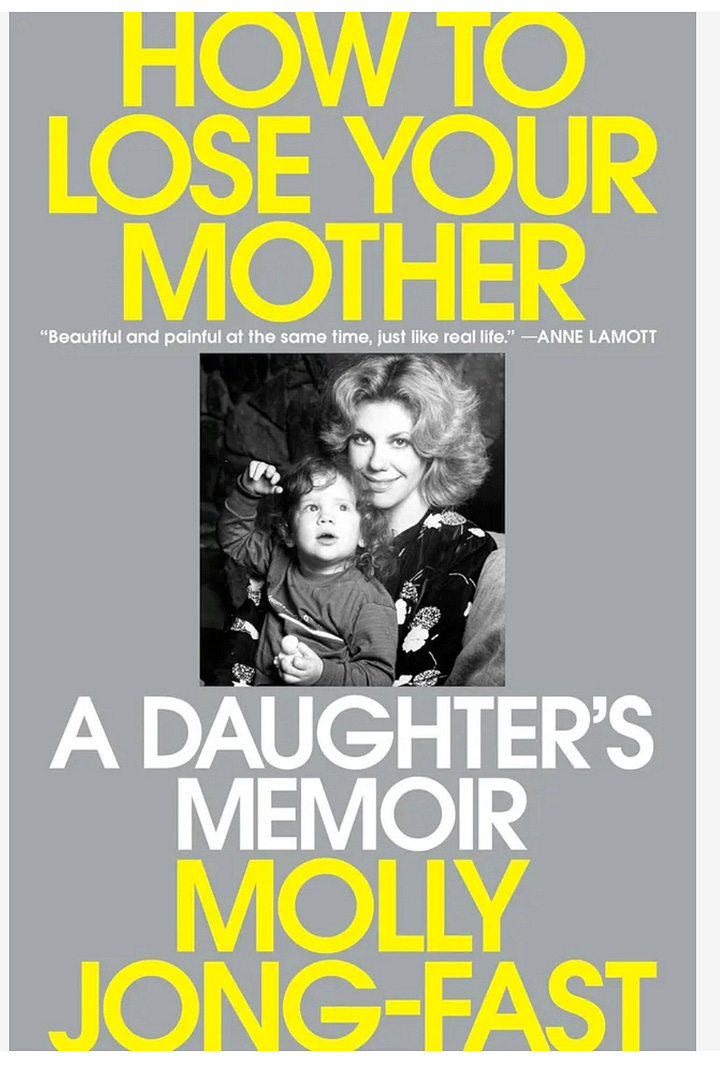

If you’re tempted by the reviewers’ praise for Molly Jong-Fast’s “How to Lose Your Mother,” I hope you’ll read “Fear of Flying” first. Get acquainted with that Erica Jong first. Actually, if you’re over 70 and/or feeling yourself diminished in any way by the inevitabilities of aging—harsher for some of us than others—I’d recommend that you not read Jong-Fast’s book at all. I could be the literary critic, and tell you everything I enjoyed about her writing (she’s funny) and everything I’d mark up with a red pen (the constant use of parentheses to say that she shouldn’t have said what she just said: “Mom still had a few friends, but she always had trouble getting along with people who were not men she wanted to seduce. (I probably shouldn’t say that, but it’s true.)”] But the most striking thing about the book, for me, what lingered for days and what none of the (extremely positive) reviews will tell you is how cruel it is.

I wasn’t expecting that. What happened to the tv-Molly that I’d felt so much affection for? And how could Nicolle Wallace gush over how “moving” and “beautiful” the book is? Does she know that Erica Jong is STILL ALIVE?? That she has said in interviews that she plans to read the book? That for many readers, what Molly Jong-Fast has to say about her mother will be all that they ever know about Erica?

I’m not talking about the kvetching about how terrible her childhood was (although I could do without the politically correct qualifications: she knows how privileged she was, yada yada.) Excavating the miseries of childhood is a standard trope of memoirs, and a major reason why people write them (although it’s kinder to wait until the offending parent is dead.) And I don’t mind—in fact, appreciate—her honesty about her ambivalence about her mother (Hated her/adored her. Admired her/was embarrassed by her. Etc.) But Molly isn’t just ambivalent; she has a score to settle:

“Sometimes I would wonder if the person had read my mom's books and knew something terrible about me, like how bratty I was, or that I couldn't read all throughout lower school, or how I was fat even as a toddler, or how I had had a terrible time learning my letters….Now, somehow, the tables are turned and I'm doing to her exactly what she always did to me.”

Actually, it’s hardly “exactly what she always did to me”—because Erica Jong, despite her daughter’s assessment that she’s completely forgotten (and wasn’t such a good feminist to begin with) is still well-remembered by many feminists of her generation. So this memoir isn’t just pillaging her life (as Erica did to Molly), it’s also an expose that tears into Jong’s persona and legacy as a writer—and does so quite ruthlessly. But at the same time, Jong-Fast doesn’t want us to think bad things about her (that is, about Molly,) so she’s constantly telling the reader that she knows and feels terrible about how mean she’s being, what a bad daughter she is. But she’s gonna do it anyway:

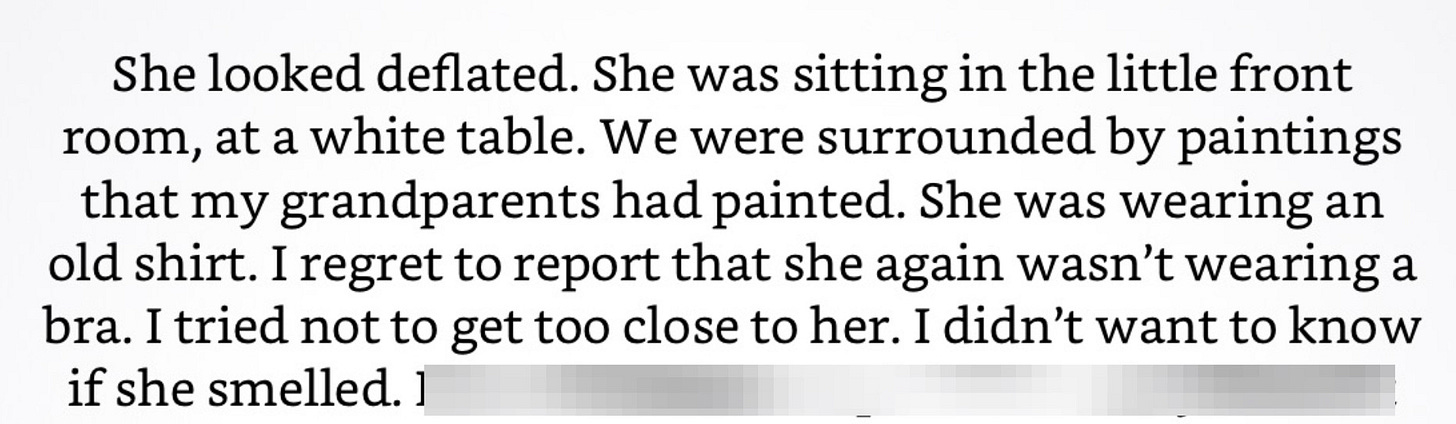

Example: “Mom sat nervously in the front row. Her head kept bobbing. She now has some kind of neurological thing that makes her head bob back and forth like a chicken pecking seeds. I know that’s a mean thing to say.” My feeling: If you know it’s such a mean thing to say, just don’t say it! Or, on the other hand, if you feel you have every right—as a neglected daughter or as a writer—to say mean things, just go ahead and do it and have the courage to risk the reader’s judgment.

This disingenuous two-step doesn’t seem to have bothered most reviewers. More than that, some of them seem to have relished the cruelty and been conned (as I see it) by the illusion of self-awareness and self-judgment created by the “I know this is a terrible thing to say, but….”

The starred Kirkus review of the book:

“It has never been easy to be Erica Jong’s daughter; her total involvement with her career and with the men in her life absorbed all her time and energy. ‘She couldn’t even spend one hour with you,’ Jong-Fast’s father tells her. ‘The most she could do was half an hour.’ There was a nanny, private schools, fancy hotel rooms, trips to Venice, celebrities galore, but it was far from a happy childhood: ‘I was born to privilege, born on third base, but desperate to strike out and go home.’ By the age of 19, Jong-Fast was in recovery; this, her 26th year of sobriety, was marked by the continuing damage and sorrow of her mother’s alcoholism. ‘So much of our lives have been about alcohol that it makes me want to cry.’ Jong-Fast is obsessive and merciless about her mother’s drinking as well as her many other profound character flaws, and the miracle of this book is that you feel no need to judge her for that. Her honesty, her self-awareness, and her grief keep you on her side, as well as her humor, understated, blunt, and sometimes black. A typical reflection: “My dad has a moral core, a kind of spirituality and a quest for joy that I do not have. I’m not even sure I’d want it. Which is perhaps not the greatest self-analysis.” “I am a bad daughter,” she tells us over and over, but it’s pretty clear she did the best she could. (Emphasis mine)

I wonder how old this reviewer is. I wonder if he or she has any familiarity with the books that (along with all the men) “absorbed all [of Erica Jong’s] time and energy”? (Molly herself has never read them—understandable for many reasons but not a trivial detail.) I wonder why he or she didn’t feel the tiniest bit queasy putting a quote about the dad’s “moral core” in the same paragraph as the mom’s “profound character flaws.”? I’m amazed at how easily he or she is disarmed by the “I am a bad daughter” mantra. Maybe Molly actually does stew over her deficits as a daughter. But the reader isn’t a therapist or an old friend, and these “confessions” seem designed to make sure that we won’t judge her for exposing her (STILL ALIVE) mother so “mercilessly” (the one word I salute in this review.)

Merciless: How your demented (and STILL ALIVE) mother refused to bathe, how dirty she was, how she smelled, how her hair was unwashed, how you found a turd in her bed. All mentioned several times.

What exactly is the point of these embarrassing bodily details? Is there some kind of confusion here between being an “unflinching” writer and having no concern for the privacy or humiliation of others? Molly isn’t the first author to privilege her writing over everything and everyone else, and there is room for genuine disagreement over what the writer owes others in her life. Some writers feel that leaving things out with other people’s feelings in mind is a betrayal of the writer’s art, or a kind of dishonesty. Others—I count myself here—have books they long to write but just can’t, because it would mean exposing people they love. (I probably fall on the extreme end of that debate, so keep that in mind if you’re getting angry with me for my criticisms of Jong-Fast.)

What’s unusual about “How to Lose Your Mother” is that Molly wants to have it both ways. She doesn’t spare her mother anything. In the book, there’s nothing much to like about Erica Jong the neglectful parent and self-absorbed seeker of fame and adulation. The Erica Jong who actually wrote books is totally absent except for a few paragraphs at the end of the book when Molly seems to recognize that she should at least nod in that direction. That’s fine. This is a daughter’s memoir, not an assessment of her mother’s accomplishments (which I remind you again, she hasn’t actually read.) But then, she claims to want the reader to feel affection for the person she’s given the reader no reason to like:

“I want you to empathize with my mother. Something happened to her, something in her childhood that made her disassociate. I don’t know what it was. She never knew either, but whatever it was, it made it impossible for her to stay in her own body. I just don’t want you, the reader, to blame her. I truly don’t think any of this was her fault. Also, I want you to know that she missed so much of her life. I don’t want you to hate any of these people, but I do want to write about how bad her own parents were, and that having bad parents made her not responsible for the way she parented me. I want to make you love all of them, make them sympathetic characters. I want to explain to you how my mother was a deeply broken person who went from man to man trying to find an identity.”

Molly tells us that she wants all of this—for us to empathize with, to not blame, even to love her mother. But if that’s true, why doesn’t she put her money, so to speak, with her mouth is, and show us why we should? She’s writing the book, after all, the one who decides what details, what scenes, what descriptions to put in it. If you’re going to be merciless—with whatever justification, for whatever reason: getting even, purging oneself, writing what you consider to be an honest book—own it. Don’t be “mean” (Molly’s chosen word for it, not mine) and then try to tell us that’s not what you meant to do.

But maybe this isn’t Molly Jong-Fast the writer speaking. Or even MollyJong-Fast the daughter. Maybe it’s Molly Jong-Fast, the sweet, modest girl from tv who is speaking. Maybe she’s struggling, as girls do, with the contradiction between what she feels and what she’s supposed to feel. She doesn’t want to be seen as a “mean girl.”

When I think about it this way, I still feel protective of her.

At one point in the book, Jong-Fast (again in that don’t-hate-me, “self-judgmental” mode) muses: “Do I pretend that I am absolved— or at least safe in my public judgments about her— because I know she will never be able to read what I'm writing?” This was confusing to me, both grammatically and factually. Molly seems to be saying that she is reassured (whether in bad faith or not) that her mother, presumably because of her dementia, will never read the book. But in a recent interview1 (in which we may be surprised to see that she is still “on the planet”) Erica Jong says she plans to read the book, and expects it to be “unsparing” of her:

“When you’re a writer, your life is really an open book, and that’s true also for your child,” said Ms. Jong, who sounded sharp and cheerfully upbeat about her daughter’s memoir, noting that she hadn’t yet read it but planned to.

Asked about Ms. Jong-Fast’s bleak account of her upbringing, and her descriptions of Ms. Jong’s excessive drinking and more recent health issues, Ms. Jong seemed unfazed, and said she expected her daughter’s memoir to be unsparing….

“I write about her, she writes about me,” Ms. Jong said. “If you want to be an honest writer, you have to speak about it all. None of it bothers me.”

I don’t know if Erica is being truthful here. Molly is quoted in the same article as saying that “Had she been with it, she would not like it [the book]. Even though she always said my whole life that I could write anything I wanted about her, I don’t really think she meant it.” It’s interesting, though, that mother and daughter appear to share the same philosophy that “in order to be an honest writer, you have to speak about it all.” Of course, no one can “speak about it all”; whether conscious of it or not, we’re always selecting, the act of putting words together in any form is a selection. What Erica really means is: “all” is fair game for the writer. And she means it. One thing Molly’s memoir finally settled for me is whether Isodora Wing is “drawn from” Erica’s life (as is the case with many novels) or Isadora Wing and Erica Jong are virtually the same person, just with different names. I had the feeling, when reading “Fear of Flying,” that Erica came home every night and wrote down every detail of her experience that appears in the book. I’m sure that isn’t exactly true. But it’s truer than not. If it happened to Erica it was worthy of putting in the book: chapters on every husband, endless details about every city, every happening on Isadora’s travels with Adrian Goodlove (Nabokov was her favorite author, and it shows—but the cross-country trip of Humbert and Lolita is great, singing writing, and this section of “Fear of Flying” is tiresome.)

In the same article, Alexandra Alter writes that “longtime friends who stay in touch with Ms. Jong, including Susan Cheever, the singer-songwriter Judy Collins and the novelist Ken Follett, say her long-term memory seems intact, but she’s forgetful and disoriented at times. She sometimes doesn’t recognize old friends, or her grandchildren, said Ms. Jong-Fast, who has three children.

‘At first Erica isn’t sure who I am, then after a few minutes she remembers, and for a while she seems like her old self,’ said Mr. Follett, who has known Ms. Jong since 1980.

It seems, from this information, that Erica Jong hasn’t become “just a body.” Do we ever become “just” bodies? Even at our most diminished (some say even in a coma), we still experience. I don’t even know what “just a body” in a still-living person could mean. What does seem true—and painful for any aging person to be confronted with—is that once we are marked as elderly, our bodies become fair game for humiliation, and, as was the case with Joe Biden, proof that we are exiting the planet. I think of Biden not to compare him to Erica Jong “in reality”(I haven’t the information or expertise to do that) but because I recently reviewed Jake Tapper’s book, 2which claims to be about Biden’s “cognitive decline” but is actually more about his “shuffle,” the stiffness of his “gait.” His tripping over a sandbag. His speaking in a whispery voice. His need for naps in the middle of day. His trouble with steps. The fact that his aides tried to get him to take longer strides and to not let his mouth hang open. Donald Trump is just a few years younger than Biden. He’s a cognitive mess and it’s getting worse all the time. He trips on stairs too. But because he’s physically “robust” and doesn’t talk softly, he’s never described as “elderly.”

I’m not disputing that Erica Jong suffers from dementia, or that’s it’s been painful for her daughter Molly to witness her decline. I’m pointing to how we get marked as decrepit or not by the degree to which our bodies appear to be aging. I’m pointing to how the revulsion we feel over the aging body bubbles up, even when “cognitive decline” is the issue. I’m pointing to the way we talk about that decline, oblivious to being cold or hurtful—almost as if we don’t have to take care, because there’s no longer a subjectivity inhabiting that body. It was the poop in the bed. I feel pretty sure that Erica Jong wouldn’t be ok with that.

Freud wrote that “no one can be a man unless his father has died.” Jung added: “Yes, but that death can occur symbolically.” “How to Lose Your Mother” shows that’s true of daughters and mothers, too. Maybe it’s true, too, of the various “generations” of feminists. But as I said earlier, that’s for a different stack (I suppose I’m reminding myself to write it.)

After I read “How to Lose Your Mother” I had nightmares for days. I felt as though I could be dead at any minute, that my attachment to life was so fragile it could snap just like that. I don’t usually feel that way. I have a pretty normal assortment of aches and pains for a 78-year-old, and I often have trouble remembering names. Almost everyone my age does. I don’t suffer from dementia—at least, I don’t think so. I’m probably a better writer than ever. Except for back and balance problems caused by a messed-up disk, I usually feel pretty sturdy. When I feel anxious—which is frequent, but it’s always been that way for me—I start writing or get on the exercise bike and I feel better. I hate the crinkly skin on my once smooth arms, so I avoid looking at them.

I’ve thought about it for days, and the closest I can come to understanding why Molly’s book created such death-anxiety in me is that, because of my sisterhood with Erica (Jewish women with chutzpah and big hair, same generation of raunchy, intellectual feminists) Molly had redefined me along with her mother. At the beginning of her brilliant “Illness as Metaphor,” Susan Sontag writes:

Illness is the nightside of life, a more onerous citizen ship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

The same is true of the kingdom of the young and the kingdom of the old. Reading “How to Lose Your Mother” made me feel more decisively like a citizen of the kingdom of the old, of the expiring, than I usually feel. In part, that’s because it’s my writing that keeps me feeling like I still live in the kingdom of the young, whatever is changing in my body. And it’s precisely Erica Jong the writer that gets disappeared in Molly’s book. What remains is a smelly old woman who poops in her bed. What remains are books that (at least according to her daughter) no-one reads any more.

*Fair use is a legal principle that allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission, particularly for purposes like criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Obviously, I’m not using the term here as referring to copyright law, but metaphorically.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/31/style/molly-jong-fast-memoir-erica-jong.html?unlocked_article_code=1.OE8.fbhz.cXNOdyE6Tonf&smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

Susan, you brave writing soul - you always get straight to the bullshit behind media platitudes. This piece is so sharp, well-argued, and personally vulnerable - all the qualities you’ve convinced me are missing from Molly Jong-Fast’s memoir. I read an excerpt a few days ago, and it disturbed me, too, for many of the same reasons. I also thought it was very poorly written (that faux self-awareness and “should I say that?” you mention). The mostly positive reviews stagger me.

I thought she was writing about her mother in ways I never would, and I had a problematic artist mother myself. In fact, I’ve been doing some memoir writing about my mother, but my focus has been on her art and the dissonance within myself. Big ego, mental illness, nastiness - you can’t separate an artist from their work.

One of my biggest rules as a personal nonfiction writer and teacher of this form is that you should never expose other people more than you expose yourself. Molly JF may think she’s done that my talking about her own recovery, but based on what I’ve read, she hasn’t looked hard enough at herself to figure out why she wrote this. It saddens me enormously that nobody pushed her to go deeper and to exhibit kindness as well as daughterly hurt.

Thank you. My mother and I are (were- she’s been gone awhile) both second wave feminists. I had unusual, brilliant, often oblivious, sometimes neglectful parents myself, and I wrestle with their legacy. I cannot imagine writing a memoir of this ilk. I read a couple of reviews, and cannot understand how this elucidates anything important for the public understanding of either mother or daughter. Write it out in long hand, get it all on the page, share it with your therapist. But don’t inflict this on the world.