Diana Redux

With “The Crown”’s final season now streaming, I look back on some of my past writing about Diana.

“It had nothing to do with family trees. Something in her personality, her receptivity, fitted her to be the carrier of myth.” (Hillary Mantel)

1. In an Empire of Images, the End of a Fairy Tale

Note: Diana Died on August 31, 1997. It happened while I was at a Women’s Studies week-end retreat. There had been a lot of eating, a lot of laughing, and—because we were developing a curriculum—a lot of arguing. But when, in the morning, we heard about Diana’s death, we surprised ourselves and each other by being overcome with shared.grief. This essay, which I was commissioned to write for “The Chronicle of Higher Education,” was written just a few days later, and I was angry about how she died, pursued by paparazzi. Reading it today, at a time when so much of what I wrote about in those days, both here and in my books, has engulfed our culture and even given us a POTUS who rides entirely on salable image, my ending plea and hope for us to moderate our indulgence in what Sontag called the “insatiable” eye of the camera, seems naive—and sad. Did I really think things could change? Or was I just needing some kind of closure for my essay?

In the universe of mass culture, there is a world and a counterworld, in constant conversation with each other. One world is glossy. In posed fashion spreads and slick celebrity features, the glossy world feeds our eyes and focuses our desires on creamy skin, perfect hair, bodies that refuse awkwardness and age. It delights us like visual candy, but it also makes us sick with who we are and offers remedies that promise to close the gap-at a price.

The counterworld is grainy. It grabs us at the supermarket check-out, where our backs are aching and wallets hurting, where children may be tugging at our legs.

The grainy world used to be largely a sideshow featuring the bizarre: three-headed babies, alien abductions, man buried alive for six years survives. Today, it thrives also on sagas of cancer, miscarriage, and weight gain among the rich and famous.

Despite their perfect teeth, these people are like you, the stories tell us—you, at the Grand Union check-out, with your dying father, your struggle to get pregnant, your rebellious thighs.

Celebrities are "real people." Beyond the deceptive headlines and false rumor-mongering, the tabloids thus offer a measure of truth. But like the glossy publishing world, tabloid journalism is a highly profitable industry and doesn't know when to stop. The poised, perfect bodies must be exposed tripping on their gowns, caught without makeup, in illicit clinches. Paparazzi—waiting, watching for the unguarded moment—are a mainstay of the grainy world.

Princess Diana's image was a staple of both these worlds, which together comprise most of what we call "the media" in this culture. The words "journalism" and “press,” evoking pens, pencils, type, are relics of another time. What we have today is an empire of images, affecting us more like a drug-delivery system than as a relayer of information and ideas. On some level, many of us "know" this but accept our addiction to visual junk as normal. Will Diana's death—a defining moment for an image-obsessed and money-driven culture—force us to recognize how bizarre and dangerous this "normalcy" is?

So far, we've been drifting on a sea of obfuscation, denial, and self-justification.

Thousands of people today—not just photographers and journalists but advertisers, film makers, video producers—are deeply implicated in the continual mass production of titillating images. Yet somehow, no one takes responsibility

On the August 31 broadcast of CNN's “Reliable Sources”—the day after the Paris car crash—the National Enquirer's Stephen Coz described the paparazzi involved in the chase that ended in Diana's death as a "breed apart," guilty of "renegade behavior" far outside the impeccable standards of Enquirer photojournalism.

"We didn't hire them," he said. Perhaps not oflicially. But to whom were these “renegades" (all employed by big-time photo agencies, some of them award-win-ning photographers) hoping to sell their pictures?

In her turn, Janice Min, senior editor of People magazine, bristled at being placed "in the same league" as the tabloids. But asked if People would publish photos taken at the scene of the crash, she said she was waiting to see what other publications would do. Min was a chilling exhibit of the moral vacuum in which the "stalkarazzi" have blossomed.

From People and its highly profitable spinoffs, it's just a skip and a jump to the seemingly more sober Time and Newsweek. Now that Stephen Coz has called for a national boycott of the crash-site photographs, it is unlikely that these magazines will buy them. But reaching my mailbox with breathtaking speed on September 2, Time's "Special Report" on Diana's death printed a photo (taken by whom, I wonder?) of Diana just about to enter the fatal Mercedes.

Is the eye that this photo is designed to "inform" so very different from the eye that the stalkarazzi were banking on, as they snapped photos of Diana's still-moving, yet mortally injured, body?

I found my own eye turning, against my strong efforts otherwise, back to the Time photo. I was appalled both at my own ghoulish fascination and at Time for indulging it. I remembered Min's excuse:"There's a market out there for these photos. People want to see them." True enough, but when did market demand become moral justification? Do the media bear no responsibility for nurturing that demand?

The Monday after the crash, I had watched Mary Tillotson, anchor on "CNN Live," react with barely suppressed glee to the discovery that the chauffeur of the Mercedes may have had an illegal level of alcohol in his blood. Tillotson, like many other television reporters, was clearly uneasy with having blame for the fatal crash placed on the photographers' pursuit. She sensed, rightly, that criticism of the paparazzi is the tip of an iceberg, below which flow dangerous waters for the more mainstream press.

It was the "legitimate" press, after all, which, sensing the possibilities of a sensational story--"The Hero Turned Suspect"-so zestfully painted a portrait of Richard Jewell to fit the "profile" of a “lone bomber." When it turned out that Jewell could not have been the Olympic Park bomber, the press blamed the F.B.1. and had the chutzpah to invoke the "people’s right to know" to justity their own inflammatory headlines.

[Sidebar: The piece you’re reading was written in 1997; this one was written a couple of weeks ago:

The old media establishment helps out the new image makers by providing some traditional, noble principles for cover. The New York Times warns, "There is not likely to be any regulatory approach to the abuses of the paparazzi and their outlets that does not compromise the essence of an open society." Nice rhetoric, and I’m sure truly believed. But as precious as a free press is, it may need to be redefined for an image-dominated culture. It was Susan Sontag, in On Photography, who first diagnosed the ways in which the "insatiability of the photographing eye” is producing a “chronic voyeuristic relation to the world.” Sontag presciently described the “predatory" qualities implicit in "every use of the camera,” qualities that have a particularly concrete and menacing reality today.

First Amendment absolutists overlook the fact that the Founding Fathers were as remote from a culture in which images inundate and invade our lives as they were from the moon. Those who formulated the First Amendment believed themselves to be protecting words, and words are different from photographs. I sit in my study writing about events that are past, occurring across the globe, or only of my imagination. The photographer’s subject, in contrast, must be concretely present, and this intimacy raises new moral dilemmas. How far may we intrude on an unwilling or unknowing subject? Is taking a picture before seeking help for an injured subject an act of criminal negligence? Intelligent discussion of First Amendment rights requires historical perspective on the new media, not high-flying rhetoric.

Princess Diana's brother, Charles Spencer, said "blood is on the hands" of every publisher and editor who has paid for intrusive and exploitative photographs of Diana. I would go further. Blood is on the hands of all of us, and it's not easy to clean off. Is the Enquirer's boycott of the crash photos a showy, one-time gesture of moral outrage or the beginning of a new policy? A restrained tabloid may be a contradiction in terms.

A consumer boycott of the tabloids, as many movie stars are suggesting, would be a start. But can consumers, at this stage, moderate our now highly developed needs for stimulation, sensation, titillation? If we did, how many industries would collapse? To imagine these things actually happening is to envision a culture dramatically transformed. Yet perhaps this is just what we must begin to envision.

As the media—both glossy and grainy—have turned their machinery to the production of heartwarming images in commemoration of Diana, it's clear how easily they can process into pabulum the sentiments and insights of intelligent and feeling individuals. Despite this, the struggle to understand Diana's appeal and the reason that so many of us--including feminist critics of the media like myself—feel so sad about her death is important.

The New York Times described her as “not a . . . historical figure. Her arena was “entirely one of images and gestures.” Like the many Western Civilization textbooks that focus only on men’s wars and political maneuvers, the Times’s anachronistic view of history begs to be cracked open. Ironically, Diana’s death did just that.

Images are what late-20th-century history is made of. Can anyone doubt that the global outpouring of grief for a woman largely known through images of her glamorous beauty is an event of historical importance? For most of us, there is no Princess Diana outside the stories spun by the media. Yet she managed to break through some unexpected warp in the celebrity galaxy, leaving many people feeling that they knew her.

Perhaps this illusion of intimacy with Diana had something to do with her efforts to be "real." Most stars don't engage in that struggle; they luxuriate in their privileges as objects of fantasy.

The supermodels deny that they diet, which leaves thousands of young women feeling inadequate because they obsess about food and hate their bodies. Diana acknowledged that she, like they, binged out of emotional emptiness and then vomited to stay slim. That exposure, as any woman who has suffered from the shame of an eating disorder knows, was hardly a mere "gesture."

Diana was a princess bride, but an unloved one--and, in defiance of the script that she was supposed to play out, she told us so. We have no access to the "real truth" of her life with Charles. But she was willing to let the fairy tale become a different kind of story, and it was one with which many women could identify. Then she was killed, in a grisly ending befitting the Brothers Grimm more than the world according to Disney. A shudder went through those of us, raised on tales with moral cautions, whom femininity has taught to feel "wanton" for wanting sexual fulfillment, "selfish" for trying to create our own stories.

Diana always was a real person, of course; with her violent death, that realness has become a wrenching, completed lesson. True, the photographers who pursued her and clicked photos at the crash site didn't get it. They saw Diana as an opportunity, not a person. Perhaps, however, our continued acceptance of such opportunism as business-as-usual has been sufficiently disturbed by that last mental image of Diana, helpless as photographers swarmed around her broken body. It's hard to believe that no one will publish those pictures. But I hope for a day when we will no longer think we need to see them.

[September 19th, 1997]

From “The Revenge of the Consorts”

Note: This piece is the second half of an exploration of the commonalities between Anne Boleyn, whose cultural afterlife I wrote about in The Creation of Anne Boleyn. (For the whole piece, including the section on Anne that I have not reposted here—see my substack “Royal Bodies Part Two: Anne and Diana”) Since I wrote it, there have been several significant variations on Anne—including one (the film “Spencer”) that makes the Anne/Diana connection explicit, by having the ghost of Anne haunt Diana, warning of her own fate. And then, too, there’s been the real-life royal drama created by Prince Harry’s marriage to Meghan Markle. At some later point, I would like to carry this piece through to the present, and include these. Please do contribute your ideas!!

Fifteen years ago, when I was talking to prospective editors about my book, one—from a major press—said skeptically “Do you really think there’s still interest in Anne Boleyn?” Luckily for me, she was a bit out of touch. With “The Tudors” came the websites…and the tee-shirts, mugs, and jewelry…and the facebook pages…and a whole new stream of bios, novels, films, and plays.

Anne, a wife whom Henry desperately wanted to erase, is in fact his most represented consort. Post-structuralist theorists would say that this makes sense: what we try to bury or make marginal, by its very suppression, keeps making itself known—and with the aid of modern media, deployed in a multiplicity of ways. Henry could destroy the symbols that HE had created, but he couldn’t prevent the unfolding of a cultural afterlife that so far shows no signs of ending. Ironically, Anne—who wasn’t born to be royal—wound up having the immortal body of royalty, as a cultural creation.

July 22, 2013: Three months earlier, The Creation of Anne Boleyn had been published, and my book’s Facebook page had been filled for weeks with postings about the upcoming birth of Princess Kate’s royal baby. The world was entranced with the latest unfolding of the fairy tale. I was swept up, too, but also growing annoyed at what seemed to be the eclipse of that other princess—the one who wasn’t quite so skilled at behaving as Queen consorts-to-be are supposed to. Princess Kate seemed so different from Diana, “whose human awkwardness and emotional incontinence showed in her every gesture.” (Hillary Mantel) Her biographer Rosalind Coward, who does know her better than most, wrote that she presents “no immediate danger of going off like a loose canon…Unlike Diana, this is a woman well-briefed and carefully supervised.” When the queen embarked on a series of Diamond Jubilee tours of Britain’s provinces, she even “took with her the newly minted duchess as if to finally lay to rest Diana’s ghost.”

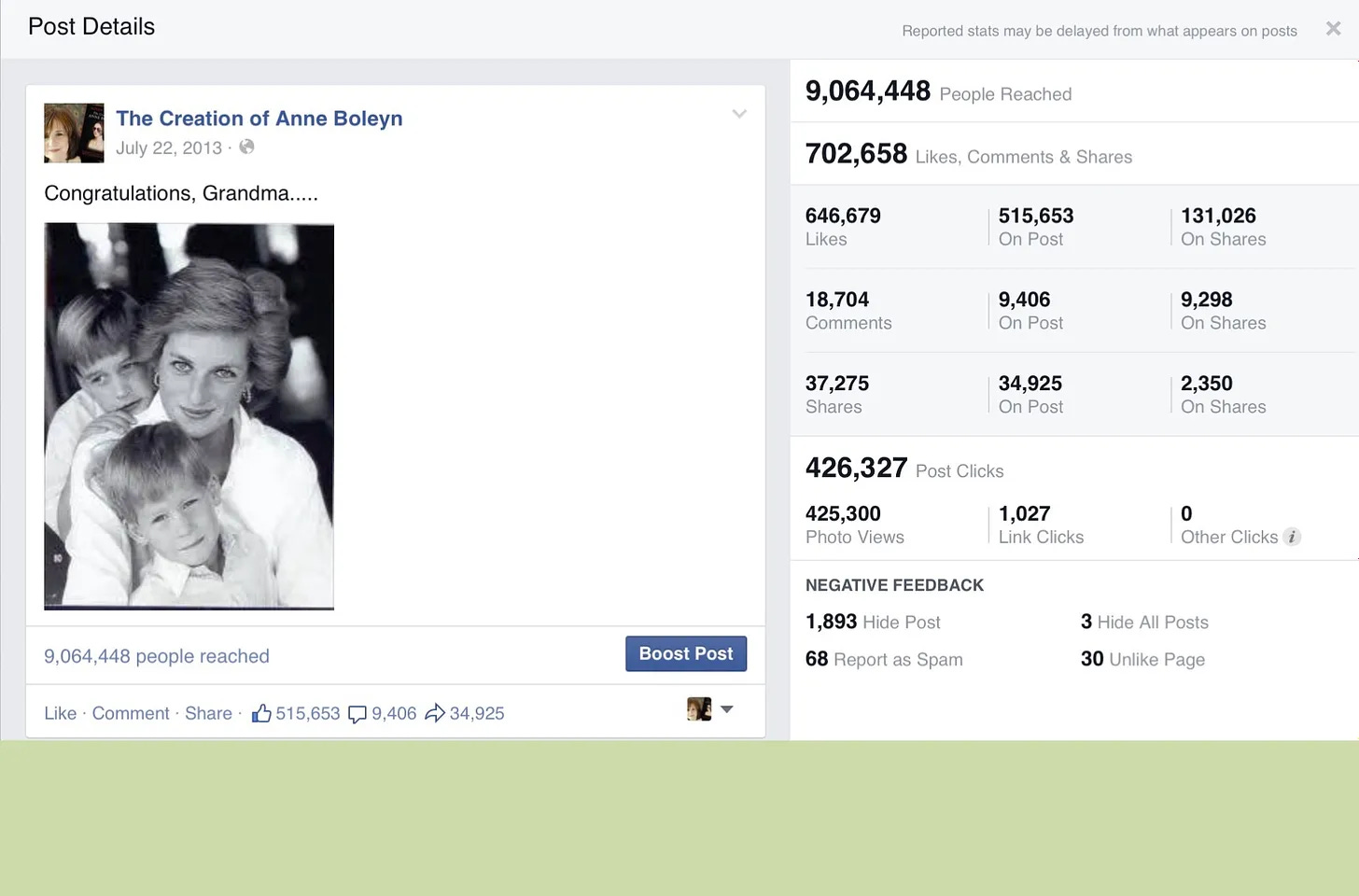

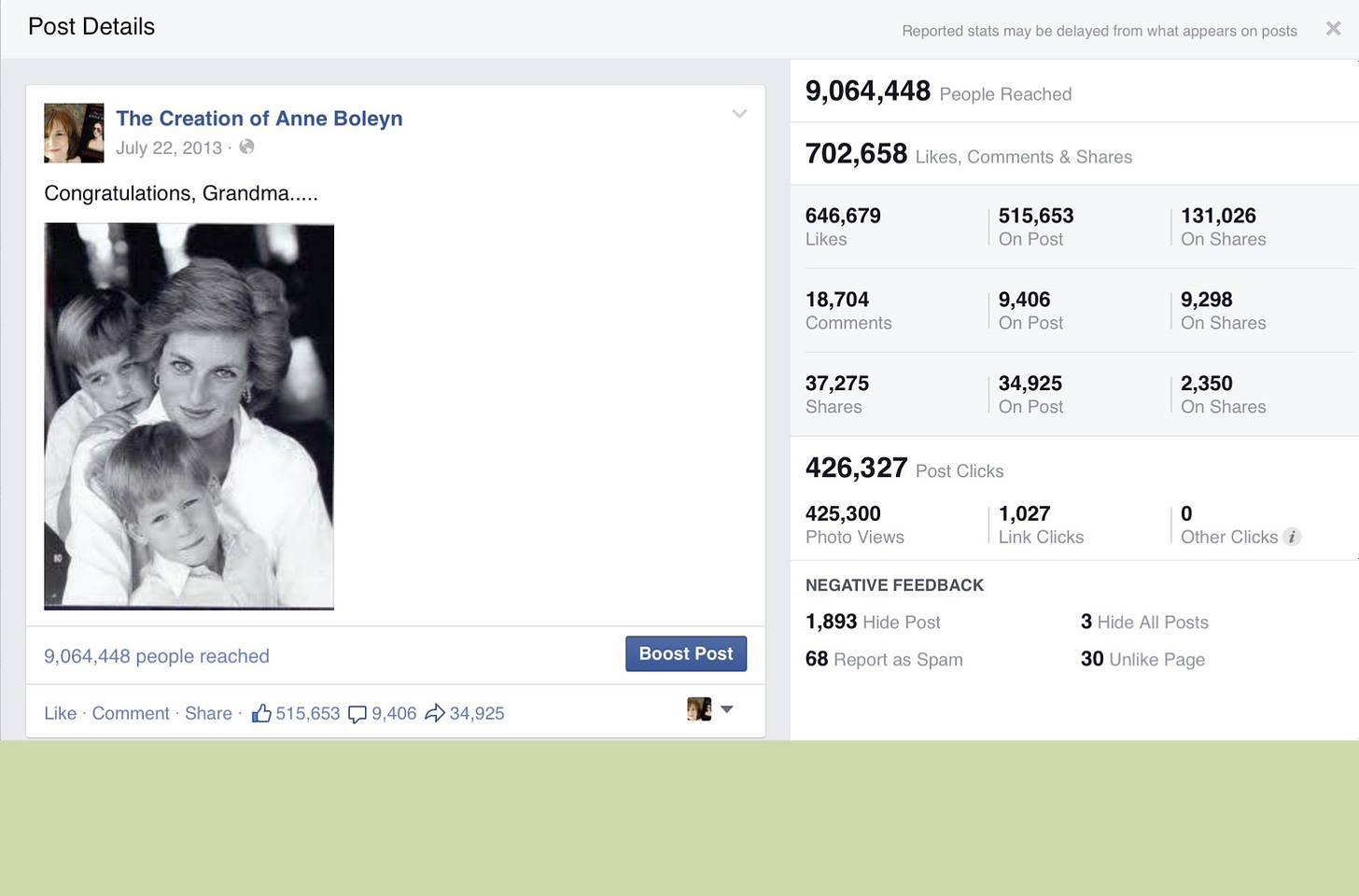

It was irritating. Didn’t anyone remember that there was another Princess for whom the fairytale didn’t end so happily? Why isn’t there any mention of the “royal bump’s” (as it was called during Kate’s pregnancy) deceased grandmother? Have we so easily replaced one glamorous mama-goddess with another? Annoyed, on the day George was born I posted this photograph of Diana and her sons, with the caption “Congratulations, Grandma.” It was purely for my own satisfaction; I didn’t expect more than a few dozen “likes”. Instead, the post went viral, and the comments extolling Diana poured in by the thousands.

And it struck me that this picture was every bit as much an icon as Holbein’s Henry VIII or Elizabeth I’s Gloriana. And I was put in mind, too, of the queen about whom I’d just written a book.

Diana and Anne seem on the surface to have little in common, with Diana now venerated and Anne constantly caricatured as a nasty, narcissistic schemer. But scratch the surface of the stereotypes and their sisterhood appears. Like Anne, Diana had challenged the power and authority of the monarchy to decide what her rightful role as the future King’s wife should be. Diana, too, had been viewed by her enemies as a bossy, overly ambitious, non-royal interloper who refused to behave as she should and was unwilling to tolerate the infidelity that good wives were supposed to endure in silence. Instead of waving and smiling while her fairy tale fell apart, Diana spoke up, drolly remarking, in her famous Panorama interview with Martin Bashir, that her marriage was “a bit crowded” as there were “three of us in it.”

The initial price she paid for her failure to be silent was to offend a powerful network of country club and court who, for a time, seemed in control of the situation: “The mantra,” wrote one of Diana’s biographers, “was that Diana was a scheming girl who had set her cap at Charles and got him…[But] she [turned out to be] impossible to live with,” ferociously possessive, and “cruel and domineering” both to her staff and Prince Charles. Sound familiar to Anne Boleyn aficionados?

But Diana, unlike Anne, had weapons to fight back with, chief among them a modern media machine capable of promoting her personal glamour and warmth, as well as her caring, maternal activities. People particularly cheered her refusal to accept that being emotional did not go along with being royal. “I lead from the heart, not the head,” she told Bashir. But that was just fine as far as Diana was concerned, for she wanted to reign not officially but as a Queen of Hearts, giving affection and helping others. Quite an interesting reversal of the age-old notion, which has often been used to contrast Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I, that rulers must choose in favor of intellect over love, male mind over female body. It all depended on what sort of throne you wished to sit upon, Diana suggested.

With her death, however, the worship of her as “Queen of Hearts” exposed that even the official throne was in need of more “heart” when the Queen, at first, stayed away from the mourning crowds and refused to fly the royal flag for Diana. “Show us there’s a heart at the house of Windsor” the headlines blasted, a painful moment for Elizabeth and one of the themes of Stephen Frears The Queen, which shows Elizabeth II as utterly baffled by the seeming change in the rules of the game. She’s done what she thought was expected of her, only to find that she was hated for her coldness and formality. She confides in Tony Blair:

“Ever since Diana people want glamour and tears…the grand performance…and I’m not very good at that. I prefer to keep my feelings to myself…foolishly I believed that’s what people wanted from their Queen. Not to make a fuss nor wear one’s heart on one’s sleeve, duty first…self second. It’s how I was brought up, it’s all I’ve ever known.”known.”

Diana, of course—and again like Anne Boleyn—was not brought up to be a royal. She didn’t even know much royal history, and fantasized about marrying prince Charles, “the only man,” she said, “who couldn’t divorce me.” “It could be quite fun,” she said to a friend. It would be like Anne Boleyn or Guinevere.” Her apparently more educated friend replied, “I bloody hope not!” For good and for bad, Diana’s marriage did turn out to be more like Anne’s marriage than she would have wished had she known her history. Although Charles was never passionately in love with Diana as Henry (apparently) was with Anne at the beginning, Charles was no less surprised than Henry to find that his wife actually expected fidelity from him—and no less outraged when she called him out on his behavior. Like Henry, he was rattled by Diana’s unwillingness to recede into the background. Like Henry, he expected that once she was out of the picture, not in death but in divorce, it would all go back to normal.

Has it? Or has Diana, like Anne, become “more royal than the family she joined”?

Just watched Elton John sing his grief at the funeral.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFC8ObVw5kQ

The death of Diana brings back memories for me of the death of JFK Jr. They both happened in the summer, and both were a form of royalty I suppose. They seemed to happen one after the other and I thought of them together.

I was in my thirties when the two tragedies happened. Now, looking back i can see how different the tragedies were. JFK Jr. tempting fate to the point of irresponsibility, Diana chased to death and leaving behind a family and a country truly in mourning.