Exclusive Interview with Hilary Mantel

Never before published! Conversation with the mega-award winning writer. PLUS my 2015 review of “Wolf Hall” books and play.

Hillary Mantel’s sequel to Wolf Hall, entitled Bring Up the Bodies, had just been published when I posted this interview. She was not yet finished with the sequel when we corresponded; in fact, was at that point not planning a trilogy, but a long second volume. Her publishers convinced her, however, that her section on the fall of Anne Boleyn constituted a book on their own—hence, the decision to enlarge and publish that section as Bring up the Bodies. I had promised Hilary not to post the interview until the sequel was published. Before now, it has never been published anywhere except on my personal website.

SB: We all know that any work of imagination has to go beyond the recorded facts. But do you think that there is a point at which historical fiction can go too far? What historical standards do you hold yourself to?

HM: First let me say I don’t want to defame other authors for their choices. I don’t want to prescribe for them or defend them. I don’t think there’s a right way of creating historical fiction, but I think some ways are more honest than others. I am probably less comfortable about ‘making up’ than most authors. I never knowingly distort facts, and even if they’re difficult to explain or for the reader to grasp, I try to find a way round that doesn’t falsify or sell short the complexities of a topic.

I must see myself as part of a chain of literary representation. My Cromwell shakes hands with the Cromwell of the Book of Martyrs, and with the trickster Cromwell of the truly awful but funny Elizabethan play about him. I am conscious of all his later, if fugitive, incarnations in fiction and drama.

I am conscious on every page of hard choices to be made, and I make sure I never believe my own story. (Bring Up the Bodies) raises the whole question with the reader, hands it over if you like: points out the power of gossip once it gets going, the difficulty of separating rumour from facts, the difficulties of bearing witness and assessing evidence. I don’t talk about these problems in a narrative overview, I make them part of the plot. I don’t think AB was brought down by facts, but by the power of rumour. That’s a slippery and insubstantial thing to describe, and almost impossible for historians to tackle. By its nature, conspiracy is off the record. The important conversations probably leave no trace. I think this is why historians try again and again to disentangle the mystery of AB’s fall, without ever sounding entirely convincing. There’s always something that is left over, something unaccounted for, a piece of territory that vanishes when you try to map it. I think this is where fiction operates best, and can possibly contribute to our understanding of the past. I can’t explain the events better than historians can, but I might be able to evoke what it was like to live through those days.

That’s the largest claim I will make for fiction.

SB: In an interview with me, Michael Hirst complained that while people were constantly criticizing “The Tudors” for its departures from historical record, “Wolf Hall” got nothing but praise for its almost entirely imaginative universe. Care to comment on that?

HM: I think there’s a difference between the sort of making up I do and the sort the creators of ‘The Tudors’ went in for. They decide that fact is not always neat enough, and that fiction can improve it. They think, for example, it’s too complicated for the viewer if Henry has two sisters, so they roll them up into one. So then they have to invent an imaginary king for the composite to marry. And so we get further and further from anything resembling the record, because one falsification trips another. They decide they don’t need too many geographical noblemen — not Norfolk AND Suffolk: so they dispense with AB’s uncle, one of the unignorable figures of Henry’s reign; and that’s a really bad choice, not just historically but dramatically, because they miss all the fun of having a man who helps execute both his nieces.

Re Philippa Gregory: Retha Warnicke’s eccentric interpretation of Anne’s fall is a gift to novelists because it’s so sensational, but it’s very much a minority view. Through PG’s fiction, it’s gained traction. It’s through fiction that it’s become popular, though historians are mostly dismissive. I have to admit to some reservation about PG’s methods, not only because she relies heavily on one interpretation but because I have heard her claim that Mary Boleyn was an obscure figure until she rescued her: whereas of course you can’t read much about Henry’s reign without encountering Mary Boleyn, whose existence was a vast canon law complication. She’s even a character in that old film ‘Anne of the Thousand Days.’ However, PG evidently knows her readership and what they want.

SB: I noticed that in the earliest novels, authors often had a section devoted to outlining for readers what was created and what is factual in their works. We tend not to do that any more. Why not? And what do you think of such a practice?

HM: A section telling readers what’s true and what’s false? You can certainly do that in outline, but if I myself were to do it properly, the notes would be longer than the book; almost every line would have to be parsed. Can I give an example? In the winter of 1535 a man otherwise unknown to history wrote to Thomas Cromwell to explain how he had made a snowman. It was made to look like the pope. It was ‘for the better setting forth of the king’s supremacy.’ But his local priest and his associates broke his door down, barged in and accused him of heresy. Can Cromwell help?

This made me laugh very much, and I can bet that was the effect on Cromwell too. (How do I know he had a sense of humour? Letter writers send enclosures, ‘put in to make you laugh.’) So in my book, when TC comes home from court one chilly late December twilight to his house at Stepney, he finds that snowmen have been constructed in the garden (the pope and his cardinals) and everyone under thirty (and some over thirty) has spent the afternoon at this, for, as his son says ‘the better setting forth of the king’s supremacy,’ and they are also having a bonfire, and dancing around it is led by Christophe (fictional) and Dick Purser (factual.) So what now is the status of the snowmen?

To create an episode like this gives me great delight and I try to think why. I am happy that the original snowman isn’t lost for ever, that it has been, as it were, rebuilt, only to melt again. I think about myself, thinking about the letter writer, whom perhaps no one has thought of for hundreds of years. And it works dramatically because gives me something silly and joyous to counterpoint the dire things happening that night: Katherine of Aragon is dying, Chapuys is ready to take to the road at dawn, Stephen Vaughan will be right behind him, etc. And it’s something so true of its time, that I could never make it up, would never dare (though everyone will think I have) and it hints at that whole world of Tudor ‘misrule’ and the annual breakdown of authority that marked the turn of the year, which always sounds so unconvincing when it’s described in folkloric texts.

SB: Some defenders of Philippa Gregory have argued that “all history is interpretation anyway.” This was said, too, by Natalie Portman, who played Anne in “The Other Boleyn Girl.” Neither she nor Scarlet Johansen nor Eric Bana did much research beyond readed PG’s novel, because “all you got from historians was competing views, anyway.” Care to comment?

HM: Having argued that there are not two neat categories, ‘fact’ and ‘fiction,’ I still think the notion that ‘it’s all interpretation’ must be qualified; some interpretations are well grounded in fact and context, others are not. I spend a lot of time seeing if I can reconcile interpretations, and I do as much research and reading as I possibly can. But I know I can’t proof myself against errors or misperceptions. And that’s why I don’t like to look down on authors who write quicker: I might this very day be generating some vast error, the more vast because I’ve tried to know so much. But I referred above to the idea of being ‘honest’ and I guess this is what I mean: at least, put the hours in. Respect the dead.

You have to think what you owe to history. But you also have to think what you owe to the novel form. Your readers expect a story. And they don’t want it to be two-dimensional, barely dramatized. So (and this is queasy ground) you have to create interiority for your characters. Your chances of guessing their thoughts are slim or none; and yet there is no reality left, against which to measure your failure.

SB: In our “post-Oliver Stone, post-O.J. Trial” era, in which viewers/readers may no longer have much ability to distinguish between different kinds of narratives, do you think the fact/fiction issue has become more problematic?

HM: A problem: what readers think they know. Fiction is commonly more persuasive than history texts. After Wolf Hall was published, I was constantly being asked ‘Was Thomas More really like that? We thought he was a really nice man!’ I could only answer, ‘I am trying to describe how he might have appeared if you were standing in the shoes of Thomas Cromwell: who, incidentally, did not dislike him.’ But of course what I was really up against was A Man for All Seasons: the older fiction having accreted authority, just by being around for two generations. When I say to people, ‘Do you really think More was a 1960s liberal?’ they laugh. ‘Of course not.’ But (again, for the sake of honesty) you constantly have to weaken your own case, by pointing out to people that all historical fiction is really contemporary fiction; you write out of your own time. General readers are always asking you for the ‘real truth,’ and suppose that historians know more than they do: that they have ready access to a corpus of reliable, contemporary, first-hand reports, and that the perverse choice of the historical novelist is to deviate from these, in order to be sensational and sell more copies.

Re AB, I think it’s an obvious point that she is carrying our projections; we (women readers especially) hang our story on to hers. This explains the undying appeal of the story of Henry VIII. Usually, to bring women characters to the fore in the writing of history (factual or fictional) you have to force the issue a bit. You have to position them centrally, when they weren’t really central, to pretend they were more important than they were or that we know more about them than we do. But in the reign of Bluebeard, you don’t have to pretend. Women, their bodies, their animal nature, their reproductive capacities, are central to the era. Also, you have at least 2 queens, Katherine and Anne, who are very well documented compared to most women in history: the same goes for the princess Mary. Not only are they documented, but they are real players: politicians, strategists.

But. There is a big ‘but’ coming. These women operated in a masculine context. Can you understand their stories if you stay down among the women? I don’t think you can. And I don’t really understand the appeal of doing so. But I’m very interested in how some popular novels use Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn as ‘teaching material.’ Women’s lives are thus, and thus: do this and you win: but then you get paid out. They are made into moral tales; which, indeed, they were to the contemporaries of the women concerned. It’s rather worrying that the morals drawn are much the same, across the centuries.

EXTRA: MY 2015 REVIEW

I admired Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies very much. But I was struck by the fact that while every other character was creatively re-imagined, her portrait of Anne, particular in did not depart from what I call “Our Default Anne.” I was also struck by the particular historical events Hillary decided to leave out—those that “softened” and complicated her portrait of Anne—and the fact that, despite what she says in this interview, she defended those choices as “historical.” I had some critical things to say in my book, and also wrote several pieces about the problems with historical fictions claiming to be factual. I’ve continued to wrestle with this issue and appreciate the fact that creatively imagined histories (like “Queen Charlotte,” which I reviewed on BordoLines) have revived the old practice that I ask Hillary about in this interview, and announce clearly that they are fictions.

I continue to admire Wolf Hall and I very much mourned Hillary’s death. We lost a great creative writer.

My 2015 review appeared in Huffington Post UK

“Why Not Just Admit It’s Fiction?”

When I interviewed Hilary Mantel in 2011 while she was still writing Bring Up the Bodies, she described her characters as belonging to "a chain of literary representation." Her Cromwell, she told me, "shakes hands" with previous depictions, as does her Thomas More, a bold departure from earlier depictions such as the sanctified, witty dropout of Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons:

"[W] hat I was really up against [in Wolf Hall] was A Man for All Seasons: the older fiction having accreted authority, just by being around for two generations. When I say to people, 'Do you really think More was a 1960s liberal?' they laugh. 'Of course not.' "

But Mantel understood that her More, like her Cromwell and her Anne, reflects cultural projections and agendas no less than Bolt's. "All historical fiction is really contemporary fiction," she told me, "We always write from our own time." She was reluctant to criticize other authors for their "choices." "I never knowingly distort facts," she told me. But history is full of factual chasms and moral ambiguities, and "I might this very day be generating some vast error."

“I make sure I never believe my own story" she said.

All that seems to have changed now that her books have been made into a play and television series, widely praised by the press and touted by Mantel herself for its historical accuracy. Keeping careful watch over The BBC's adaptation so as to avoid what she has called the "cascade of errors" and the "nonsense" of historical dramas such as The Tudors, in recent interviews Mantel has declared the series a success. "History is never a convenient shape, it's true, but if you have the craft and the will to do it, you can find a way to tell a good story without distortion." She is delighted "that accuracy remained a priority" in the series. Commentators have overwhelmingly agreed, from the not-always-scrupulous Daily Mail ("Accuracy is king in the most eagerly anticipated TV event of the year...You won't find a zip, or Velcro, even in the crowd") to historian Lucy Worsley (who finds "no flaws" beyond the fact that "Jane Seymour is too pretty.") A notable dissenter is David Starkey, who as usual undermines his own critique by lathering it with bile, calling Mantel's version of characters and events a "deliberate perversion" of historical fact.

Virtually alone in his calm candor about the inventiveness of Mantel's universe, the show's director Peter Kosminsky is both more modest in his claims for accuracy than Mantel, but unlike Starkey does not find anything "perverse" about its license with fact: "Wolf Hall is revisionist history, there's no doubt about it. There are people who take strong exception to her interpretations, particularly of Sir Thomas More. Is this the truth? I have no idea. We set out to shoot Peter's script. This is our attempt to bring Hilary's books to the screen, no more or less."

Thank you, Mr. Kosminsky. Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies are indeed revisionist "history," and not just in the depiction of More. Operating (although not consistently) with the literary device of how people and events "might have looked from Thomas Cromwell's point of view," Mantel gives us portraits of people and events that are often factually unsupported and sometimes downright contradicted, and so far the series is following her lead. Its portrait of Anne Boleyn, for example, is a rather tired old stereotype of Anne as a coldly ambitious, narcissistic schemer that seems to be written more from the point of view of Anne's political enemy Eustace Chapuys than Cromwell. In the novel, Mantel sustains that "mean girl" stereotype by excluding some key historical events that the real Cromwell, whatever his feelings about Anne, would have witnessed or known about - Anne's eloquent speech at her trial, for example, and the one at the scaffold. In her author's note, Mantel "justifies" the omission of the speeches, citing skepticism that they actually occurred. But this is odd, not only because there are multiple corroborating reports of both, but also because Mantel had a few sentences before told her readers that she claims no historical "authority" for her version of things. (It seems she is no longer skeptical about the scaffold speech, as it has apparently been included in the television series.)

Only two episodes have been broadcast so far, so we will have to see whether the series follows the novels in omitting other key incidents that don't buttress Mantel's view of Cromwell. It's a matter of historical record, for example, that Anne's longtime ally Thomas Cranmer, shocked by Anne's arrests, sat down to write a letter to Henry expressing his amazement at the charges against her. His writing was interrupted however (as Cranmer relates when he resumes), by a visit from Cromwell and his cronies. They apparently helped him to "change his mind" about Anne's guilt, for the letter ends very differently than it begins, with poor Cranmer, clearly quaking in his boots, acknowledging that she must be guilty. Mantel chooses, in Bring up the Bodies, not to tell us about the interruption. Perhaps the detail would have made Cromwell seem more like a thug than she wished to portray him.

All this, of course, is Mantel's prerogative as a novelist. Why then not admit that it's that prerogative rather than concerns about historical accuracy that account for her exclusion of Anne's speeches as well? Why not admit, in other words, that the world she has created, while situated in history and peopled with characters that had an historical existence, is fiction. What on earth is wrong with that? Why all the PR about the historical "rigor," "accuracy," many years of research, etc. that went into the novels?

Fiction can put us in touch with truths that no history text can attain, and should be proud of its ability to do just that. Mantel's novels brilliantly capture the cozy but claustrophobic world of Henry's court and the tightrope nature of survival within it. And her Cromwell is a compelling personification of the kind of man who could prosper in that season. Mark Rylance's performance in the BBC series is both still and magnetic, and I would watch the show for it alone. But let's not suppose that just because the clothes have no zippers and the gardens are not manicured that Mantel's Cromwell (or Anne, or More, or Wolsey) are more "historically accurate" than A Man for All Seasons or The Tudors.

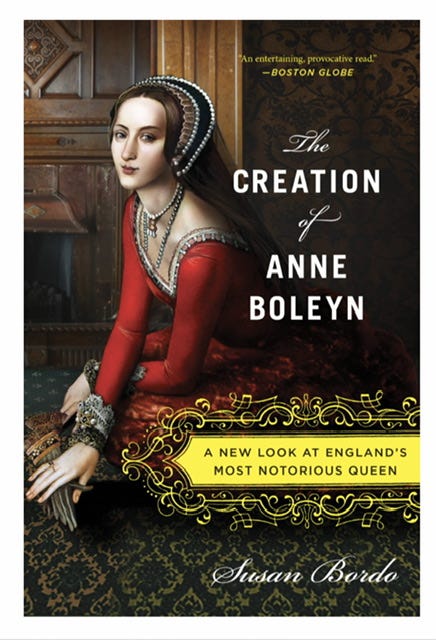

Susan Bordo is the author of The Creation of Anne Boleyn, now available both in the US and in the UK in paperback.