“The particular greatness of movies,” Pauline Kael once wrote, is the power to connect with us “emotionally…in spite of our thinking selves.”

“I love that ‘in spite of.” If you’re looking for a treatise, you may as well skip the film entirely and enroll in ‘An Introduction to Existentialism’ or ‘The Postmodern Condition’.” I wrote those words in a review of “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” a film that irritated me for many reasons but that had one scene that illustrated exactly why I was left cold about the rest of the movie.

In that scene, mother and daughter, in one alternative universe, become rocks—a large one that keeps trying to get closer to a smaller one, as the smaller one cringes and inches away. They also share a laugh together. And alone in a silent universe they apologize, reassure, flirt with getting closer, then back away. It’s a moment (since immortalized on tee-shirts and mugs) when the relentless action, technical dazzle, and swirl of ideas jammed into the film is put on pause, and the heart is touched. That big rock and that little one, truly speaking to each other—without karate chops, hot dog fingers, or even mouths—on the edge of a cliff, alone together in a vast open space. Those rocks say more about the tender estrangement that exists between mother and daughter than the corny reconciliation at the end of the film. It’s perfect little gem.

In the mysterious ways of art (but not philosophy) those rocks get to us “in spite of” our thinking selves.

A lot of people were annoyed, some even furious, with me for not liking EEAAO. It wasn’t the first or the last time. I didn’t like “Oppenheimer” or “Poor Things,” either, both highly celebrated. I had lots of arguments about those films on Facebook, which I expected.1 But I didn’t expect the reaction I got to a few sentences I casually threw up on my page after seeing “The Substance.” I’d been unusually out-of-touch with movie-world ever since the Biden/Trump debate threw the election “coverage” (scare quotes deliberate) into overdrive. For many months, BordoLines was almost exclusively focused on politics. After Beelzebub won, it was time for a catch-up.

Honestly, I thought I was being non-controversial when I posted this, about “The Substance”: “Maybe it’s meant to be funny. Maybe it’s meant to be a feminist horror film. Whatever. It’s a ridiculous movie that’s almost unbearable to watch.” What made the movie “almost unbearable to watch,” for me, was the stomach-turning imagery. But I’ll take blood, guts, and vomit from traditional horror movies that don’t take themselves so seriously. What makes “The Substance” “ridiculous”—besides the absurdity of presenting Demi Moore’s preternaturally preserved face and body as that of an aging women—is the pretentious, metaphorical use of that imagery to make a well-worn “feminist” point. Writer/director Coralie Fargeat:

“The movie is about women’s bodies, and to me, I couldn’t find a better way than body horror to show the violence that we can do to ourselves. That was the real metaphor. There is symbolism to play with that flesh: ‘This is what we have inside. There is the white, lovely smile. And behind this, it’s a whole other world. I’m going to show you the inside world. And yes, it’s that violence, it’s that bloody, it’s that uncomfortable, and it can be that fucked up.”2

Fargeat, who studied political science (but I’m guessing not by feminist writers) for three years before going to film school, apparently didn’t notice how “uncomfortable” being a woman is until she was heading toward 50: “I had this huge wave of: ‘My life is going to be over. I’m not going to be interesting anymore. No one is going to look at me anymore. My life is finished.’”

I suppose if you’re slender and conventionally pretty, the self-hatred women feel toward their own bodies may not come as an insight until aging sets in. As an “ethnic”-looking woman with thick calves and ankles and a life-long weight-problem, I’ve felt it all my life, even during the years when I now recognize I was quite lusciously beautiful. And I, along with two generations of feminists, wrote extensively about the “body horror’ women suffer—and there have been plenty of novels and films that highlight the common female experiences of being “too much” or “less than.” Apparently, though, it had to be turned into an over-the-top metaphor in order for it to—as Fargeat puts it—“hit people’s minds.”

“The Substance” was just nominated for several Oscars, including Best Picture. By the time of the announcement yesterday I was prepared, as I had not been a week ago, when a bunch of people whose opinion I respect responded to my mini-post, saying they loved the film and declared it “marvelous” and “outstanding”; some even aimed some nasty, personal blows at me. Eventually, though, after one of the commentators explained why the film was so emotionally resonant for her, I realized that the 40 and 50-something generation of women, unlike my own (I turned 78 today) grew up with a promise of equality and cultural acceptance that’s been so utterly betrayed, in so many ways, that only the most violent imagery is adequate to speak for their anger, their fury at being fucked-over after being told that they could be anything they wanted, that power (e.g. higher office) and equality (e.g. reproductive rights) were theirs for the taking. Not to mention the illusion created by Hollywood and the self-enhancement industries that beauty need not have an expiration date.

I grew up expecting nothing, then feminism gave me life. Anger was woven into the fabric of that feminism, but so was hope and excitement and community and discovery. We had words, we made up words, we put old words to new uses to express both the anger and the excitement. We wrote books, we theorized, we created poetry and fiction, went into politics, we shoved doors open. We didn’t need a graphic metaphor to bust through the mystifications and illusions and everyday violence; we did that by being ourselves, by thinking out loud and knowing that we‘d be mocked and dismissed and told we were ugly man-haters. We resisted in all the ways that history had prepared for us. We’re furious now, too, but we have muscle-memory of empowerment as well. And we don’t need a shock-and-awe metaphor to remind us of the violence done to women in this culture.

Thanks to the FB friend who stopped being outraged at me and took the time to explain, I understand the anger of younger generations of feminists and why “The Substance” would speak to them. But for myself, I’m never going to be swept away by films that are treatises, feminist or otherwise. Tell me a good story whose ending I can’t predict. Make me weep. Make me smile with pleasure. Turn me on. Give me one delicious image. Break my heart. Just don’t lecture me. I even prefer overtly silly feminist revenge-fantasies like “Blink Twice” or Fargeat’s first movie, “Revenge” to “The Substance.” But they are just candy; I watch “Sister Wives” for much the same kind of enjoyment. Kody is such a pompous ass; it’s fun to see him behave like it and get his comeuppance when all his wives except Sobbin’ Robyn leave him.

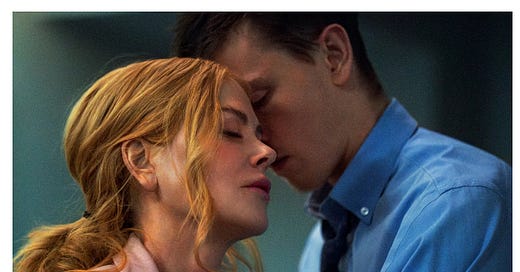

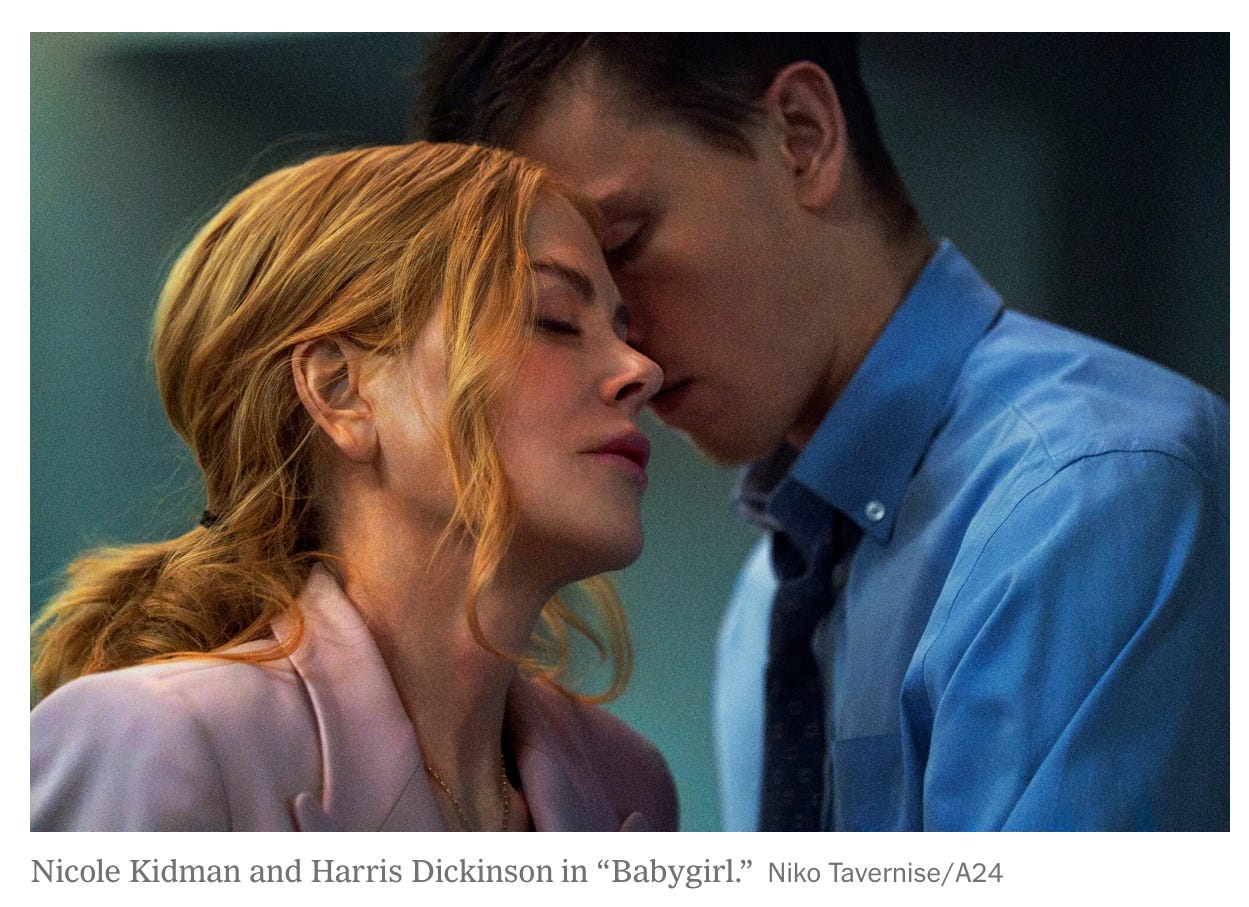

The movie that is most like “The Substance” in that it deals with (what Foucault would call) the “grip of power” on the body is “Babygirl.” But while “power” in “The Substance” is represented by a crudely leering caricature who fires Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) for being too old to star in an exercise show any more (although her body looks like that of an extremely fit 20-year old) in “Babygirl” the constraints on freedom and self-acceptance are already deeply internalized. The script (which by the way reads like a beautiful novel)3 doesn’t need a comic-book villain to trigger them.

Like “The Substance” Babygirl” was written and directed by a female film-maker—Halina Reijn—who was inspired by her own experience. “I always want to be normal,” Reijn said during an interview with The Daily Show. “My movie is sort of a letter to myself, to encourage myself to become more unapologetically my authentic self, without shame.” But rather than making a statement, the “letter” explores a question: “Can we love even the most shameful parts of ourselves?”

The “most shameful part” of Romy (Nicole Kidman, in a perfect, courageous performance that was shamefully overlooked by the Oscar nominations), a high-ranking executive at a robotics company, is that hidden behind her immaculately groomed and put-together surface are sexual needs that she has learned are not “normal”: to submit, to give herself over to the will of another, to transgress the prescribed formula for a “healthy,” “adult,” self-respecting sexual relationship based on equality. Her gorgeous husband (Antonio Banderas) clearly adores and desires her, but when she experiments, even gently, with defying that formula (for example, putting a pillow over her face while they have sex), he experiences it as kinky and disturbing. “It makes me feel like…a villain,” he says. You can understand that; I might feel that same way. Unfortunately, rather than talk about it, she feels shamed and her sexual feeling is short-circuited.

Late at night, Romy gets out of bed and masturbates to porn in which the woman is submissive and calls her sex-partner “daddy.” That little girl, masturbating under the covers to images and ideas that even some versions of feminism have declared unacceptable is her secret self, which she carefully tucks away In the daytime, as she tends to her botoxed face (yes, we see her getting the injections, a scene which in its own way breaks more movie-conventions than anything in “The Substance”), picks out perfectly appropriate outfits, puts little notes in her daughters’ lunchboxes, and practices a speech she delivers that day at work.

Later in the film, after the stitches that have held it all together have been ripped apart, she tries to explain to her husband Jacob. “Her confession,” the script reads, “comes from very deep within” and is excruciatingly halting and tortured, revealing the extent of her shame:

ROMY: Since I was very little, since I can remember even, I've always had these specific thoughts-

JACOB: What thoughts?

ROMY: Dark, dark thoughts-

She tries to find the right way to say it.

ROMY: Thoughts of - violence. Revolting thoughts. Embarrassing.

(she has a hard time saying the words out loud)

Of being -forced and hurt, and humiliated-

Worried where she is going, Jacob looks at her.

ROMY: I was so ashamed- I still am. I have no idea where they come from, who planted them in my brain. I would give anything to erase them, to delete them-

She forces herself to look at Jacob

ROMY: I see myself as a strong, smart women, who is…in control of things, who knows what she’s going—Who is loving and caring and responsible, and who wants to work on herself. Not some kind of embarrassing—masochist, or ignorant…weak, anti-feminist who—

Jacob cuts her off, pressing for details. But in fact she’s just described exactly how Jacob sees it: “Humiliation—domination—submission…whatever they call it—It’s neurotic,” he says later in the film. And then, in “correct” feminist fashion, he adds “Female masochism is a male fantasy, a male construct”

Reijn, thank goodness, isn’t going to allow any male to have the last word on what constitutes female sexual “neurosis.” She does, however, need a conduit for Romy’s liberation from the shame she feels, and that’s provided by Samuel (Harris Dickinson, who you might best remember from “Triangle of Sadness”) a 25-year-old intern who has very different ideas about what’s “normal” and who intuits, responding to subtleties at first, that Romy has a secret self that craves the relinquishing of power. He also exudes an innate personal confidence that shatters the authority that Romy has come to expect others will yield to. She’s unnerved by him even before she meets him, as she watches him—at that point he’s an anonymous stranger—calmly subdue an out-of-control dog in front of her office building. Later, when she discovers he’s an intern for her company, she asks how he did it. He says he had a cookie. But actually—I know because my daughter has that way with animals—it’s the force of his personality. (Later, in one of those brilliant sequences that can absolutely make a movie for me, Romy, while having sex with her husband, fantasizes him in the seedy hotel room where they’d sometimes met, effortlessly training the dog to obey his silent commands.)

The nuanced portrait of Samuel is part of what makes “Babygirl” one of my favorite movies this year. Unlike Christian Grey, he doesn’t have a “red room” with instruments designed to elicit pain, and his life isn’t constructed around and limited by orchestrated dominance rituals. By personality he’s a natural “alpha,” but he’s also extremely attuned to and attentive to others. He feels his way delicately and imaginatively through his relationship with Romy, which he experiences, unlike Romy, completely without shame. “I thought what we were doing—It’s like—In my mind—We’re like—two children. Playing. It’s natural” he says at one point. But as attuned as he is to Rome’s erotic needs, he’s also naively, solipsistically oblivious to the realities of her life. In that respect, he’s still actually a child. Although their sexual relationship is liberating for her, it’s not just “play” for Romy, and Samuel is genuinely surprised and distressed when he realizes that he’s seriously disrupted and injected chaos into her life. Whether or not you agree with Samuel about what’s “natural” or even like him much (his detachment stirred up some painful memories in me; but hey, being stirred—though not always painfully!—is what I want from a movie) the role is much more subtle and crafted than we typically get in movie depictions of erotic relationships.

In the end, neither Jacob or Samuel get to define and dictate Romy’s sexuality. While there are some forced illustrations of her transformation from shame to “empowerment” (she tells an office sleaze-bag to fuck himself, and husband Jacob is learning to follow her sexual lead,) her ending fantasy is neither a pronouncement of liberation or proof that Samuel the man (and training a dog!) still dominates her psyche, but just is. It’s no longer a continual struggle to excise that “most shameful” part of herself.

Riding home after seeing “Babygirl,” I thought about the difference it makes when women themselves make movies about women. Reijn has said that the film drew inspiration from erotic thrillers like “Fatal Attraction”—but with a crucial difference. Reijn: “I don’t like to punish my characters. I really love to be human about them.” That includes the men in “Babygirl,” but more significantly a “career woman” like Romy. In the days when men had a monopoly on the erotic “gaze,” women characters who dared to aspire to power in the workplace were turned into deranged neurotics whose sexuality is predatory and deformed. The original ending of “Fatal Attraction” (by writer James Dearden) was even changed at enormous expense when preview audiences felt that having Alex Forrest commit suicide was not enough punishment for the bunny-boiler. “Kill the bitch!” Male viewers shouted when a homicidal Alex breaks into the sacred space of the family home. And so that’s what Adrian Lyne’s revised version did, with the added satisfaction of giving every man’s dream of a wife (Ann Archer, looking both angelic and sexy) the task of taking down the crazed interloper.

Politically, things are a mess in 2024. It’s some small solace that female filmmakers are flourishing. Since the inauguration, I’ve allowed myself more time between stacks than I’ve ever allowed before in order to soothe my soul with movies like “Babygirl”—and “Love Lies Bleeding,” “Good One,” and “Anora,” which I plan to discuss in a forthcoming stack.

Hope to see you back here then!

https://www.indiewire.com/features/interviews/coralie-fargeat-feminist-body-horror-the-substance-1235048769/

https://a24awards.com/assets/Babygirl-screenplay.pdf

The nuance of your comments is just perfect. I needed to read your review of The Substance after watching it a few weeks ago. I was not impressed with it and was impressed that I finished watching it, gross as it was. Your comments about sex and the supposed masochism and the inner voice of women was simply exquisite. I really enjoy Nicole Kidman and plan to watch the movie in the next weeks, and am super disappointed that she was not nominated.

I agree. I thought Substance was stupid, including the (magical realism? not sure what to call it these days) of the hot young girl coming out of Demi Moore's back! I'm looking forward to seeing Baby Girl! Sounds like a much better movie. Just saw The Return last night. It was well made, engrossing!