Greta Gerwig and Girl Culture, Part 1

Dear Greta: I know I’m a “boomer” and you’re a “millennial,” but will you come play with me and be my BFF?

“Barbie” and Feminism

“It’s Greta Gerwig!” “It’s Margot Robbie!” “It’s Noah Baumbach!” “And Mattel gave them total artistic freedom!”

I spent many hours arguing, needlessly driven—because “Barbie” had yet to open—with (some) feminists and (all) defenders of the brotocracy—who finally found something to agree on: pink. They hated it and wouldn’t go near a movie that celebrated the most oppressive toy in the history of dolldom OR (if you were among the guys) was sure to be a man-hating feminist screed.

In the meantime, in between posts of my own, I was imagining what I would wear to the Barbie “Blowout Party” early screening. What was going to make it a “party”? I wondered. Will they hand out pink popcorn? I was slightly terrified of the event—not the movie itself, but the possiblity that I’d look ridiculous in my hot pink maxi dress from the “Soft Surroundings” catalogue, and blue jean jacket (to cover up my non-Barbie like upper arms). I asked my 24-year-old daughter, who is the epitome of cool, if she’d come as a beard for me, but she already had plans to go with a friend on the week-end. But as I am a responsible maven of girlhood, bodies, gender, feminism, etc. (my course on “Girl Culture” had a section on Barbie herself) I had to attend. It was research! I could even deduct the cost of tickets from my taxes. I put on my enormous earrings and my special necklace and headed to the party.

I needn’t have worried. It was one of the best nights of my movie-going life. Buttons! Posters! Gifs to download from the screen! But best of all, an audience of all ages—mostly women and girls, but some men—who laughed at all the same jokes I found hilarious, and left the theatre beaming with the delight of…well, I can speak only for myself here: for me, I felt less lonely, more in synch with a writer/director’s vision than I had in years.

For almost all my life as a feminist, I’d felt alienated from one thing or another. I hated the media sterotypes of my “second-wave” generation as humorless prudes. But 1990’s “power-feminism,” with it’s “just do it!” energy and celebrations of female “agency” missed much of the point of our (ground-breaking) critiques. I loved the racial diversity of the “third-wave” and the less puritanical attitude toward the pleasures of consumer culture. Some of the best writing on Barbie—much of which is embodied in Gerwig’s film—comes out of magazines like “Sassy”, “Bust“, “third-wave” essay collections and ahead-of-their-time books like “Barbie Culture,” by the late Mary Rogers (herself of my generation,) who would have adored this movie.

Too often, though, the “third wave” seemed to get its own motor going by throwing my generation under the bus—often unfairly and without real historical knowledge—for our “failings.” I was dismayed (and after the election, crushed) when so many white “millennial” women who claimed to be feminists flocked to Bernie Sanders, declaring Hillary Clinton a “tool of the establishment.” And then there were the coercive academic turns of various sorts, from postmodernism to transnationalism, that managed to seep into social media and turn potentially productive discussions into displays of political virtue.

But this “Barbie” movie! It was…not to be maudlin, but….it was healing for me. If you know anything about feminist writing about Barbie, fashion, consumerism, masculinity, diversity, girlhood, you’ll recognize how much it relied on the best of feminism—of all the generations—without declaring any iteration the “correct” one. And in doing so, it winked at (and then demolished) all the sterotypes—not just about gender, but about feminism. We inform the entire script of “Barbie.”Who came up with the first critiques of beauty culture and the oppressiveness of “femininity”? Feminists.Who first examined masculinity as a “gender” rather than the neuter, unraced, unsexed universal subject? Feminists (female and male.) Who was responsible for the racial and body-type diversification of toys? Feminists (Black and “white”.) Who honored girl culture and girl play, showing how imaginative and subversive much of what little girls actually did with their Barbies was? Who has been capable of endless self-critique and reinvention? Feminism.

A lot of the first complaints about the movie were from critics who hadn’t seen it (irritating in itself.) But as it turned out, once they’d seen the movie, a lot of critics cheered. “Barbie,” wrote one, “is one of the most inventive, immaculately crafted and surprising mainstream films in recent memory – a testament to what can be achieved within even the deepest bowels of capitalism…. It’s a pink-splattered manifesto to the power of irreplaceable creative labour and imagination.”

Some, mostly older “established” male critics, did get all snobby. Anthony Lane, of the New Yorker, wrote a piece full of snide barbs that manage to be anti-feminist, anti-feminine and disdainful of girl culture all at the same time:

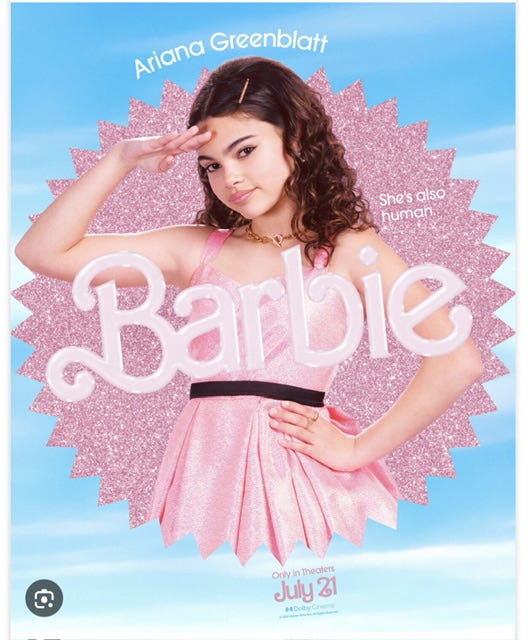

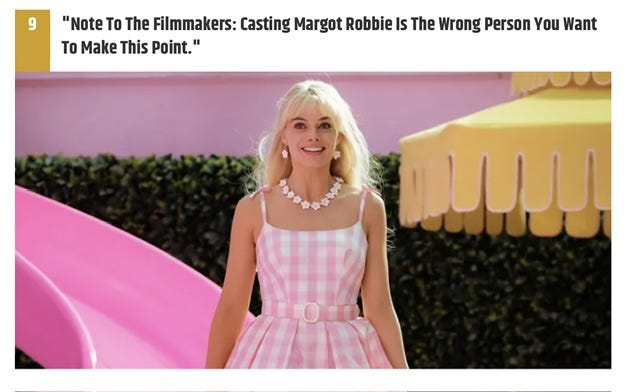

“You come away with a head full of bits: interruptions that are sprinkled over the plot like glitter. Moping Barbies tend to watch the BBC’s “Pride and Prejudice” for the seventh time, we hear, whereupon the screen fills with a clip of Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy. Wackier still is a scene in which Barbie complains of no longer being pretty; a voice-over (Helen Mirren) butts in to point out that hiring Margot Robbie to play unpretty is poor casting. This earned a laugh when I saw the movie, but you have to ask: Who’s it for? Will young girls return to the film again and again, as they did to “Frozen” (2013)? If so, what will they make of the dialogue, with its mentions of “sexualized capitalism,” “rampant consumerism,” and “cognitive dissonance”? How will they react when Sasha addresses Barbie as “you fascist”?

Maybe the movie is for Greta Gerwig. And, by extension, for anyone as super-smart as her—former Barbiephiles, preferably, who have wised up and put away childish things. Nobody else would even attempt to meld a feminist colloquium with a plug for a chunk of plastic, and, if the result is a deep disappointment after “Little Women,” perhaps depth is the wrong thing to ask for.”

Notice the swipe both at “feminist colloquium” and (implicitly) the little girls who love the “chunk of plastic.” And if he actually talked to a little girl instead of mocking their culture, he’d know they are more savvy and instinctively “political” than Lane gives them credit for. (He obviously doesn’t know that Weird Barbie [Kate McKinnon] with her chopped up hair and drawn-on face isn’t an invention of Gerwig, but what little girls actually do to their Barbies a lot of the time, in addition to arranging lots of Barbie-on-Barbie sex.)

Yes, some of the verbal allusions will go over very young heads; but 95% of this movie is going to be totally—like totally—recognizable to them. When I asked Cassie about that point (she’s going to see the movie Sunday; I saw it already), she laughed and remarked that virtually all movies that kids have flocked to are full of “adult” allusions. “They just ignore what they don’t understand, and enjoy the rest!”

Lane singled out for derision two moments I loved. The bits “sprinkled over the plot like glitter” are a big part of what make the movie fun—and so, so recognizable to us girls (and some boys, too—but not Mr. Lane.) I guess he’s never drooled over Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy. (Neither has my daughter, but she knows her mom has. Does Anthony Lane think mothers and daughters never talk to each other, or show pictures of their favorite hunks and hot women to each other?)

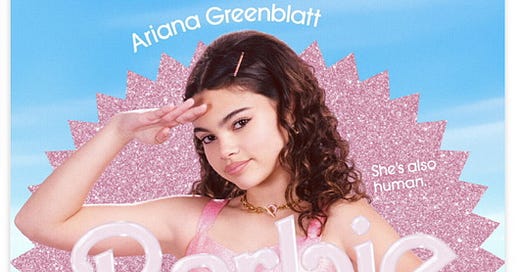

And the Helen Mirren voiceover was among the funniest moments in the movie, which like many others, broke through the fourth wall of the main script to poke playfully at the more serious themes.

He scorns the use of academic feminist jargon and apparently doesn’t notice that it too is being satirized, at the same time as it cuts through the preachier moments. Barbie’s remark that Gloria, by “giving a voice to the cognitive dissonance required to being a woman under the patriarchy robbed it of its power” is clearly meant as a spicy reminder that although Gloria’s speech about the contraditions women live with is perfectly, absolutely dead-on, this movie isn’t a feminist colloquium. It’s a comedy, Dude!!

The “plug” line is pretty annoying, too. Sure, Mattel produced it and are going to sell zillions of dolls from it. But a deal was structured so “Gerwig and Baumbach would be left alone to write what they wanted.” (“which was really fucking hard to do,” Robbie adds. ) No execs looking over their shoulders or red-lining the script. And it shows. But why does “Barbie” come in for special criticism here? Has Anthony Lane ever been in “Toys R Us”? The unusual thing is not how many dolls this movie will sell, but that, unlike “Braveheart” and other cinema celebrations of macho that have had tons of merchandise tie-ins, there’s not one single version of being female—and never has been—for Barbie to enact.

What “Barbie” and “Little Women” Share

Although Anthony Lane contrasts “Barbie” with “Little Women” (which he called “maybe the best film yet made by an American woman”—double-“othering” the film by virtue of gender and nationality) in fact, “Barbie” and “Little Women” have a lot in common.

For one thing, there is “Little Women’s” playfulness. None other than Chris Miller (who knows something about play, as the director of “21 Jump Street” and “Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse”, and “The Lego Movie”) said, long before “Barbie” was a gleam in Gerwig’s eye: “This is the most fun and most funny version of Little Women that I’ve ever seen…I remember just thinking about Little Women as a thing that is cold and dark, about sickness and people being shivering in a hole. And this movie is joyous and full of playfulness and dancing and running around on a beach and happiness. There’s obviously lots of drama in it, but it feels like a much more enjoyable experience than my vague recollections of the previous version.”

But more deeply, there is the enduring theme—shared with “Lady Bird” as well—of the challenges and pleasures of growing up girl. Gerwig has said, in several interviews, that a big influence on her thinking as she was imagining the script of “Barbie” was Mary Pipher’s Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Lives of Adolescent Girls. Published in 1994, Reviving Ophelia argues that:

“Something dramatic happens to girls in early adolescence. Just as planes and ships disappear mysteriously into the Bermuda Triangle, so do the selves of girls go down in droves. They crash and burn in a social and developmental Bermuda Triangle. ..They lose their resiliency and optimism and become less curious and inclined to take risks. They lose their assertive, energetic and ‘tomboyish’ personalities and become more deferential, self-critical and depressed. They report great unhappiness with their own bodies.” (P. 4)“Vibrant, confident girls become shy, doubting young women. Girls stop thinking ‘Who am I? What do I want?’ And start thinking ‘What must I do to please others?’ (P.7)

Leaving to one side the question of whether any of this has changed since 1994 (a question worthy of an article in itself) and staying with the idea of Pipher as an inspiration for “Barbie,” it’s not a stretch to see that Barbie undergoes, not just a universal “existential” crisis (“Do any of you sometimes think about death?”) but a crisis of “girlish” confidence when, having been chastised by a politically savvy group of young girls, she begins to question her own value and reason for being.

Until then, she’d been exuberantly happy to be who she was. But after being told off about how oppressive, racist, body-shaming she is, she breaks down crying. Although she has imagined that her purpose was to show girls that they can be “anything,” she now feels like nothing herself and—her make-up washed off and looking more like a real women than a doll, she sobs “I’m not even pretty any more.” It’s then that the narrator interjects with that bit of reality about Robbie’s looks. But almost immediately, we get another version of reality, told to Barbie by Gloria (America Ferrara) the woman whose depression has pulled Barbie into the real world:

You are so beautiful and so smart and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough.You are so beautiful and so smart and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough.

We have to always be extraordinary but somehow we’re always doing it wrong.

We have to be thin but not too thin, and we can never say we want to be thin you have to say you want to be healthy. But also you have to be thin.

You have to have money but you can’t ask for money. Because that’s crass.

You have to be a boss but you can’t be mean.

You have to lead but you can’t squash other people’s ideas.

You’re supposed to love being a mother but you don’t talk about your kids all the damn.

You have to be a career woman, but also look out for other people.

You have to answer for men’s bad behavior which is insane but if you point that out you’re accused of complaining.

Because you’re supposed to stay pretty for men but not so pretty you tempt them too much or you threaten other women. Because you’re supposed to be part of the sisterhood but always stand out.

And always be grateful but never forget that the system is rigged so find a way to acknowledge that but also always be grateful.

You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line. It’s too hard, its too contradictory, and nobody gives you a medal and says thank you.

And it turns out in fact that not only are you doing everything wrong but also everything is your fault.

I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single woman tie herself into knots so that people like us.

Some movie reviewers found this moment heavy-handed, and I have to admit that I did too at first. But if Pipher’s insight about adolescent girls motivated Gerwig, it had to be said—to Barbie and to the girls and women watching the movie. Taking down patriarchy (“Why didn’t Barbie tell me about Patriarchy?”says Ken [Ryan Gosling] dazzled by the real world) can be the stuff of hilarity.

But for young girls, the doubting of oneself because one isn’t “perfect”—according to impossible-to-fulfil standards—is a serious business. And if it can’t be cured, it can at least be called out, so no girl or woman feels alone in it. That’s was the point of the earliest “consciousness-raising groups.” And all of Gerwig’s movies embody it. She’s not interested in creating superwomen, but female characters that female viewers can identify with, from Francis Ha to Lady Bird to Barbie. Yes, even the doll with the perfect face and body worries that she’s not good enough.

Keeping on with the Pipher theme, it’s significant that all of Gerwig’s heroines are exuberant, full of energy, funny, tender-hearted, a little flaky and—except for pre-crisis Barbie—not exactly comfortable conforming to the prevailing ideals of femininity. They also crave love, but without it requiring giving up their ambitions or dreams. As Gerwig’s Jo March tells Marmee : “Women, they have minds, and they have souls as well as just hearts, and they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty. And I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for. But I’m so lonely,”

That “But I’m so lonely” may not word-for-word come from the book (I don’t remember, and my copy is buried in my garage) but it’s certainly Jo’s dilemma in the book. Of all lit heroines, Jo is the one that smart, not-so-cool, not-gorgeous girls who wanted to be writers identified with. While the happy ending of the book may have been a concession to the publisher (more about that in my next substack), to me it said: “You might be lonely now, but there’s a man out there you’ll meet someday who will appreciate you and love you.” Who won’t require that, like Mary Pipher’s adolescent girls, you give up yourself in order to please.

So although it meant going beyond the text of the book, Greta Gerwig was smart to include, in her film of “Little Women,” all the scenes showing Jo’s book being published. The girls who loved Jo didn’t just want the professor; they wanted the freedom to write, too.

There’s a real continuity there, isn’t there, with Barbie, who tells her creator Ruth Handler: “I want to be a part of the people that make meaning, not the thing that is made.”

That’s Barbie. That’s Joe March. And that’s Greta Gerwig herself. But because Gerwig is Gerwig and she’s in charge of making the meaning of “Barbie,” it has to end on a surprising, hilarious note. We see Barbie all “dolled up” in business attire, being dropped off at an office building. We imagine that she’s there to apply for a job—as a doll-creator, perhaps, maybe of “ordinary Barbie.”

Nope. She’s going to transform things more subversively:

So I’m seeing a lot of criticism here on substack in which people say that they won’t even see the movie “Barbie” because Barbie the doll is responsible for eating disorders. I’ve even had someone cancel her subscription to my substack, WITHOUT READING EITHER OF MY PIECES ON “BARBIE” (she admitted to this), because of the damage the doll has done to little girls’ sense of self-worth. And she included a nasty comment to @Substack as the reason she was “disabling” her subscription.

I can tell you—as someone who has written about the tyranny of beauty ideals since the 1980’s, including an influential book and many articles and encyclopedia pieces on eating disorders—that refusing to see the movie “Barbie” because of the doll Barbie is like refusing to see Spike Lee’s “Bamboozled” because of the damage racial stereotyping has done to Black people. Not to mention the fact that most girls who develop eating disorders nowadays aren’t trying to look like Barbie—they’re emulating the bodies of models and movie stars. (And often, it’s about something else entirely than trying to look a certain way.)

When I was still teaching, among the things that distressed me the most was the decline of the ability to discern tone and context, to recognize when something is being ironically or satirically referenced (or even deconstructed entirely) rather than advocated just because certain words or images appear.

“Barbie” is hilarious, offbeat, disarming—and yes, it does have a lot of beautiful women in it—but it’s not an advertisement for skinny bodies any more than any other movie with slender, gorgeous women in it is an advertisement for skinny bodies. And It’s a subversive deconstruction of gender roles at a time when none other than the Supreme Court is trying to make women revert to them.

And if you’re boycotting it because of the dolls Mattel will sell, please do the same for every boy-centered movie that’s made toy companies millions from action-figures…and by the way, toy guns.

I saw the movie and I loved it. It is everything you say Susan and more. I loved that I was in a theater full of girls and their mothers and WOMEN. I loved that those little girls could see all of the things you point out . I am of the first "Barbie" generation. When I was playing with her I wasn't thinking it was making a difference but it was. I hated baby dolls and Easy Bake ovens and kitchen sets. As long as I can remember I knew there was more and Barbie let me run wild with my imagination. For me she's not some sexist thing but represented freedom from housewifery. I have always thought that a gender that is the majority should in its quest for equality have enough room for all women...including those of us who love fashion and heels and lipstick.