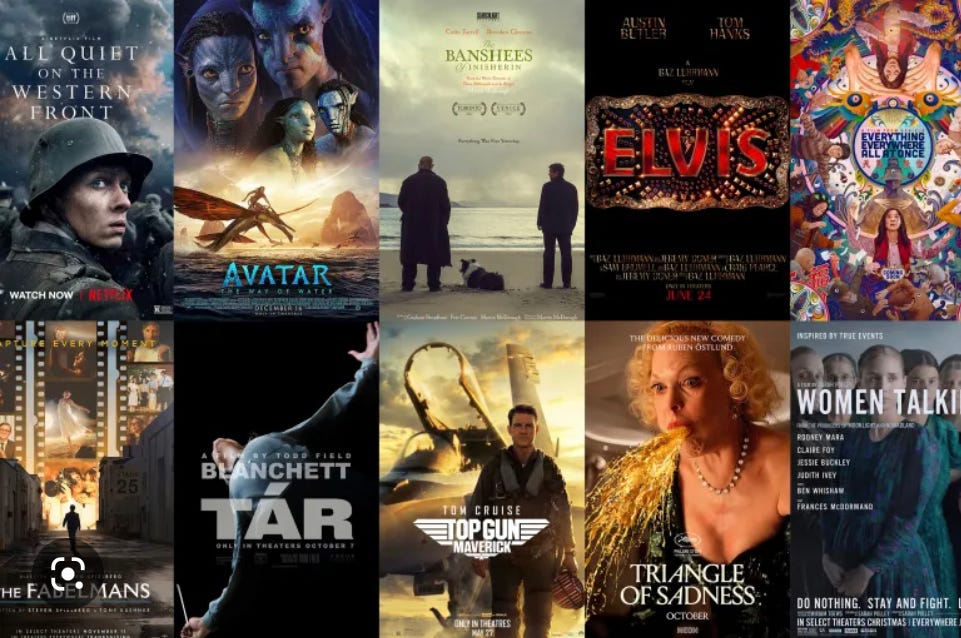

It’s the Day Before the Oscars…

…and I’ve collected some of my thoughts on the Best Picture nominees.

The Banshees of Inisherin

This is my favorite among the nominees, and I explain why in detail in my stack on the film (You’ll find a link at end of this blurb.) Today, I just want to protest the overwhelming focus on chopped fingers and donkey death in criticisms of the film. I was unnerved, even horrified by those things too (please, please, bring Jenny back to life!) but there was a reason for them, unlike the gratuitous violence that we’re so used to we’ve become inured to it. And that’s something to think about, isn’t it? These were horrors that still have the capacity to shock—as they did the characters in the movie—and wasn’t that at least part of the point? “Some things there’s no moving on from,” says Padraic at the end. That’s both a metaphor for the often pointless escalation of wars and a reality about relationships. Watch what you do and say to others, because you can go too far and create disaster. And I could add (although it may not be what McDonagh was thinking at all) the disastrous wake left by the past is also the horrible truth about the last decade of American political life. I’m not one to look for “messages” in movies, and don’t like movies that force them on us. But if you want one, this one rang truer to me than the “heart-warming,” “healing” reconciliation at the end of “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once.”

The Fabelmans

It’s not Spielberg’s best movie, and it has a happily-ever-after ending (whether or not the events actually happened, which I gather they did) that showed the way that memoirs go astray, when they allow the writer’s memories free range, even if they spoil the tone of the work. But it’s an entertaining movie that Spielberg deserved to make. I loved the details that rang true to assimilated but not quite assimilated Jewish family life (Spielberg—Sammy in the movie—graduated high school in exactly the same year as I did, and although my family never moved from New Jersey to the exotic plains of Phoenix or the coast of California, the push/pull of the “old country” ways and new “American” dreams was familiar to me.) But at the same time, the movie exploded some familiar Jewish movie stereotypes (you can see some of them even in as recent schlock as You People.) That’s the way memoir can do better than fiction. None of us grew up with stock Jewish mothers, and Spielberg especially not. Adventurous rather than anxiety-prone, serving dinner on paper plates on paper tablecloths, dancing without inhibition in front of headlines that clearly reveal her body, the mother in Fabelmans was unlike Molly Goldberg, or Philip Roth’s suffocating fantasy-figures, or the numerous yentas that have appeared in comedies, or the clueless, over-privileged mother in You People. Mitzi Fabelman, with her blonde pixie hair-cut and readiness to goof around, was refreshing. My favorite scene, though, was when Sammy runs through the footage he’s shot of a family camping trip, and discovers—through the piercing eye of the camera, which becomes the truest eye on the world for Spielberg—that something is going on between his mother and “uncle” Benny. Cutting back and forth between the images he discovers and Sammy’s changing expressions, the discovery rivetted the viewer as well as Sam. A master director at work there.

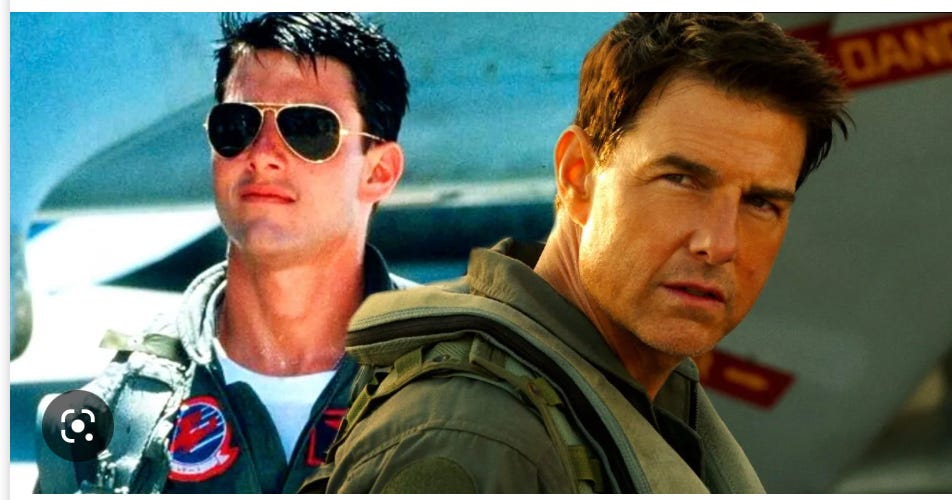

Top Gun: Maverick

Elvis

There’s something magical about the main performances in each—magical in very different ways. I have no idea whether Tom Cruise has had any “work” or not, and I don’t care. He still looks significantly older than the young Maverick, even significantly older than his last Mission Impossible, and I loved that. His neck is ropey, his eyes are tired-looking, and they haven’t used any filters to smooth away lines. To my mind—with due credit to the thrilling flying sequences—it’s what makes the movie more than just a great action flick. I also liked Daniel Craig as James Bond—I prefer male actors when the gloss has worn away--but here the actor, having played the same character earlier (as Craig did not) needs to look older, in order not to betray the sense of Maverick’s history on which so much of the narrative pivots. If Cruise had not looked as frayed at the edges, he would have been just another incarnation of the bigger-than-life hero he has so frequently played.

I generally don’t like Baz Luhrman movies, and I could complain about the things I don’t like. But I’d rather praise Austin Butler, the young actor who plays Elvis. In previous roles and in shots of him (at awards shows, etc.) he looks nothing like Elvis (As far as teen dreamboats from that era go, more like Ricky Nelson.) But Luhrman must have seen the potential in that sensuous, curled lip and sleepy eyes—and Butler apparently did a huge amount of research and worked like hell to embody Elvis—because in the movie, he not only captured the essence of Elvis’s Dionysian appeal but in some scenes looked so much like him (and sounded so much like him) it was breath-taking. I’m glad they didn’t show much of the degeneration of Elvis’s looks, too. This was a movie full of made-up fantasies (e.g. of Elvis not just being influenced—which he was—by Black performers, but being soul-brothers with some of the most famous), and Elvis himself had to be one of them. For me, especially since I wasn’t a big Elvis fan at the time (my mother was), if the movie hadn’t established (or had demolished) his sexual appeal, I probably would have been as bored by it as I was with the real Elvis. I wasn’t bored by this hot young Elvis, though, and it made all the swooning believable.

Tar

Two things the movies never get right: therapy and teaching. So much money spent getting the details of a 16th century castle exactly, and do they even visit a classroom in their research? I can’t think of a single campus-based movie that didn’t turn teachers into beloved imparters of wisdom (Dead Poets Society) or tyrants (Paper Chase) or both (Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.) Those are older movies, but it hasn’t gotten any better.

The first half-hour of Tar, in which she’s interviewed, was chillingly accurate—so accurate I thought it was a parody. I’d had dinner with those people at philosophy conferences; I’d watched them preen in seminars. When her time with an African tribe was referenced, I was ready to love this perfect send-up of the academic world I had inhabited—mostly uncomfortably—for so long.

But then they took her into a classroom. Now, I know what it’s like to have a class taken over by the culture/language/race/gender police. It’s happened to me, and it’s pretty gruesome—and not so different from what happens to Lydia in the film, except the campaign against me was waged on Facebook and it was based on virtually nothing (you’ll have to take my word on that for now; I’ll provide more detail in another post.) I wasn’t fired (this stuff was happening all across the campus) but I did have to have campus police stand outside the classroom door due to threats made against me. Tar—in contrast to the tolerant mentor that I was (chuckle)—behaves monstrously in that classroom. Again, I speak from some experience. I was a philosophy student, and a female one; I’ve been bullied by masters. But none of them would have been so stupid as to humiliate me so cruelly as Tar does that boy. Then, too, he was pretty insufferable himself, identifying himself via every letter of the alphabet and dismissing Bach because he was heterosexual. Except for that wonderful detail of his shaking leg, he was a cartoon who could have been written to specification by Ron DeSantis. (The disrupters of my classroom were much cleverer; they did most of their political maneuvering outside of class.) Maybe I’m out of touch now that I’m not teaching anymore, but during this scene I realized the pleasure of recognition—that “wow, did they nail that!”moment that I felt during the interview with Tar—wasn’t going to last.

As to what that pleasure was replaced with, some would call the movie, admiringly, a portrait of an ambiguous character, with whom we sympathize and are repelled by alternately. And judging from interviews, that’s apparently what Cate Blanchett had in mind, too. It might have worked for me if Field had just let her assert her power seductively—the soft dominance of the way she physically touches those “beneath” her, the little gifts (“that’s a marvelous handbag”) she bestows on them—and edited out the overt bullying. The film would have been more subtle and more chilling.

But, as my friend Laurel Brett noted, Cate “sure does justice to a pair of trousers.”

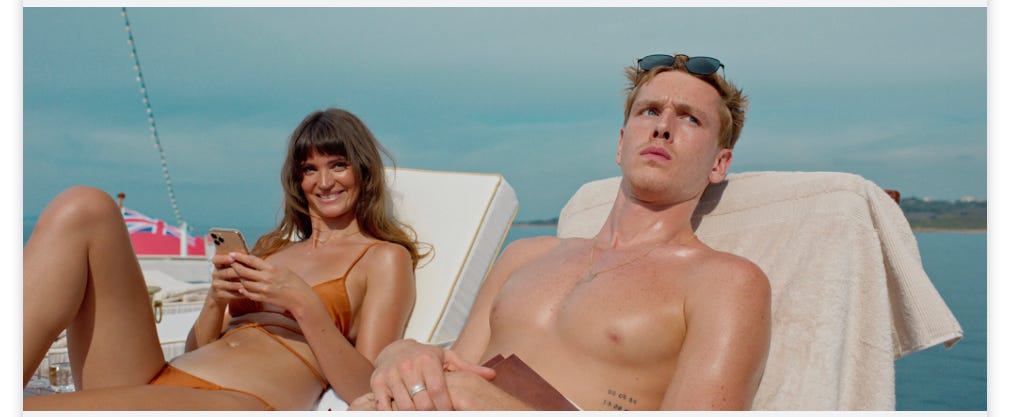

Triangle of Sadness

The first two sections of the movie—in the first, male models audition and we’re introduced to Carl, a not very successful model who just can’t relax the “triangle of sadness” in his forehead; in the second, he and YaYa, a much more successful female model--have dinner and spar over who picks up the check—brilliantly capture the weird (and for Carl, sad) , superficiality of the world of “influencers,” whose lives revolve around posing for Instagram and taking advantage of the free goodies that come with that “job.” One of those goodies is a luxury cruise, which the third section of the movie puts Carl and YaYa on, and the film shifts focus from their “culture” to the far more repellant imperiousness of the rich bourgeoisie who actually paid for their cruise. There’s an older couple who have made their fortunes “defending democracy all over the world” (he’s a manufacturer of grenades and other weaponry.) A rich Russians who literally “sells shit.” A single woman who forces the crew, who have been instructed to cater to the guests’ every whim, to go swimming. And so on. They are all so grotesque that Carl and YaYa become quite sympathetic characters. A lot of it is very funny. But then the projectile vomiting began (there’s a storm that makes everyone seasick)…and the toilets overflow with diarrhea and the woman who forced the crew to swim goes sliding across the bathroom floor in her own vomit and feces….and I had to see what was happening in some other part of my house. Yes, the whole disgusting spectacle was farce. But I didn’t appreciate being made nauseous myself by my evening entertainment. In the last section, several of them—including Yaya and Carl—are stranded on an island, and the working class gets its revenge, in the person of the toilet manager who, by virtue of her skills at catching fish and making fires, becomes the new “captain” of the island. It was pretty delicious, I will admit, to see her become the dominatrix of pretty-boy Carl. But in general, I’m not a fan of “messages” or having political ideas force-fed to me in movies. And at some point Triange of Sadness started to feel too instructive. I did unreservedly love the first two sections, though.

Avatar: The Way of Water

This one was a family affair, the first time since the pandemic that all three of us—my husband, my daughter Cassie (age 24) and me—went to a movie theatre together. So I’ll post a family review that I put up on Facebook the morning after we saw the movie:

Mom: Needed about a half hour of non-stop fighting cut. Story line and “message” corny. Visually dazzling but after awhile I felt I was being forced to be dazzled. I was also moved by various scenes and relationships, but again, felt coerced into it. Bored by first half (Cassie caught me dozing at one point) and the anti-aging serum they killed the Tulkuns for reminded me, absurdly, of the Prevagen commercial, in which they claim the “secret ingredient” comes from jellyfish. I did get swept up eventually. I’m a total sucker for an animal rescuer, and the enormous, misunderstood Payakan was especially touching.

Cassie: NO WAY SHOULD ANYTHING BE CUT, MOM! (And then she proceeded to connect every possible dot between the first Avatar and this one to show why every bit was necessary.)

Husband Edward: “I’ve never seen anything like that!” (We all had seen first Avatar, but it didn’t make as big an impression on him as this one.) But know that this is a guy who when left to his own devices with the remote watches “Columbo” and “Perry Mason” (the Raymond Burr one.) He was like a little kid with this movie.

Speaking of little kids: We all loved Tuk.

All Quiet on the Western Front

Brutal, horrifying, sad. War. That’s really all I have to say about this one.

Everything, Everywhere All At Once.

I just don’t get it. The adoration of this movie, that is. It would be one thing if it was based on the film being inventive and fun (which I didn’t find it to be) or even—as one FB friend described it—like seeing her own nervous breakdown condensed into 2 hours (not what I’m looking for in a film, but ok.) But people have come up with the most high-flying existential analyses, seen it as a feminist treatise, elevated a very, very traditional corny ending to a message about life, and knocked criticism as anti-Asian. Sorry (unsubscribe me if you must) but it feels like a cult to me. Or a runaway train. It got momentum, and then there was no stopping it.

Last night I “watched” it again, because I wanted to get my husband’s opinion. (The scare-quotes are there because I find it basically unwatchable.) It was a huge relief when our daughter came into the room with her phone, excited and oblivious to the fact that we had a movie on. She sat down in front of us, mercifully blocking my view of the tv, and for over an hour I watched one of the horses at the farm where she works give birth to a beautiful little colt.

My husband was not impressed with the film. Thank goodness. Saved again from divorce.

For more explanation of why I’m not a fan of this movie, see my stack:

Women Talking

Talking, yes. Too much talking, for my taste. For a movie, that is. (An astute observer on Facebook described it as “inert.”) As a cultural emergence, however, it’s significant that this movie was made at a time when women’s rights are being so openly assaulted. “Been there, done that,” I thought as we were walking to the car from the theatre. Not the horrific abuse those women suffered. But the awakening. For as odd as the form of the women’s speech often was, taking place among highly religious women so sheltered from the world, it had a structure and essence I remember well from the early days of Women’s Lib. For want of a better term, I’ll call it “coming into consciousness”—with all that is entailed by that: the sense of waking up to disturbing yet potentially liberating truths, the wrangling over how to “theorize” it all, the moments when that wrangling turns to holding and comforting, the recognition that one can love and also need to leave. We’re there again—or still—aren’t we, finding ourselves inside a culture that refuses to treat us as full human beings.

If you’d like to read more about how four feminist films, including “Women Talking,” remind us of this, see my substack on “Goodbye, Postfeminism.” It’s long, but you can read it in chunks. “Women Talking” is discussed in the first chunk. The other films discussed are “Alice Darling,” “Happening,” and “She Said” (which imo ought to have been nominated for an academy award.)