By and About Girls

From Little Women to Mean Girls & Margaret: Part two of my series on favorite movies adapted from other genres.

When women began to produce their biographies of famous women during the Victorian era, they were derided as “sentimental, “gossipy”, “minute,” “trifling,” “twaddling,” “amusing” and “tiddle-tattle” and disdainfully dismissed as being interested in “domestic” matters such as dress, diet, education and manners. When male historians got into such details, however, it became “social and material history.” Thomas Macaulay (1848, History of England) was enthusiastically praised for tackling “domestic and everyday life” and “the revolutions which have taken place in dress, furniture, repasts, and public amusements.”

Macaulay’s social history was viewed as a welcome “expansion” of the domain of the historian. But those that focused on women’s lives—even if that of royalty—was seen as a specialized, miniaturizing focus. Women writers were lumped together as the work of “literary ladies”—and sometimes, even the books themselves were materially linked to “women’s sphere”: Margaret Oliphant, who wrote books herself, disses the Strickland’s volumes on the lives of queens as “a shower of pretty books in red and blue, gilded and illustrated, light and dainty and personal, that fall upon us from her hands.” (From The Creation of Anne Boleyn)

“It’s just about our little life” is a line, taken from the correspondence of Louisa May Alcott, that Greta Gerwig gives to Jo March in her movie. And Alcott’s publisher agreed, finding Little Women “boring” until his niece, having found the unfinished manuscript, excitedly asked what happens to the little women (a real-life event that Gerwig tweaks and imports into the movie.)

I’m sure that J.D. Salinger didn’t regard The Catcher in the Rye as just about the “little life” of a privileged Manhatten boy in existential crisis; the critics certainly didn’t think so. But when I was growing up, books about the challenges of growing up girl didn’t even exist, except as a specialized genre that boys wouldn’t dream of reading. Nancy Drew, Cherry Ames, Little Women.

Judging from the box-office takes of both Gerwig’s Little Women and Are You Listening, God? It’s Me, Margaret, that’s how prospective viewers have seen any films that are advertised, in one way or another (Little Women in its very title) as being “about girls” or “about women.” Both films were critically applauded. But boys, guys, and fathers weren’t going—and neither were many women, finding stories of girls growing up to be too “narrow.” As Elaine Cho says of Little Women: “Even though it takes place during the Civil War, we are hardly touched by outside events other than a few scenes with Marmee.” Didn’t hear that kind of complaint about Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, not to mention the dozens of fictional film about boyhood (Stand By Me, What’s Up, Gilbert Grape, and many, many others, including acknowledged classics like The 400 Blows).

I’m not one to insist on a work passing the “Bechdel Test.” There are plenty of all-male (or virtually all-male) and male-centered novels and movies that I admire. But assign a script to a woman and/or center the lives of girls and women and I’m more than half-way there to loving the movie. Here are recommendations for a few of them.

1. Refreshing Classics: “Little Women” (2019) and “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” (2023)

Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret was written and directed by Kelly Fremon Craig, based on the 1970 novel of the same name by Judy Blume. The film stars Abby Ryder Fortson as the title character, along with Rachel McAdams, Elle Graham, Benny Safdie, and Kathy Bates.

Little Women was written and directed by Greta Gerwig. It is the seventh film adaptation of the 1868 novel of the same name by Louisa May Alcott. It stars an ensemble cast consisting of Saoirse Ronan, Emma Watson, Florence Pugh, Eliza Scanlen, Laura Dern, Timothée Chalamet, Meryl Streep, Tracy Letts, Bob Odenkirk, James Norton, Louis Garrel, and Chris Cooper.

I had never heard of “Are You there God? It’s Me Margaret” until recently. In 1970, when the book was published—with a recommended age level of 9-12–I was 23 years old and my life was more like that of author Judy Blume’s, stuck in a first marriage that wasn’t working out. I’d been through similar embarrassments to those Margaret goes through in the book. At her age, I also desperately wanted to become “a young lady now” (as the pink-and-white pamphlet inside the sanitary box napkin promised marked the blood-initiation into womanhood.) Once, in some sort of delusional state, I even scratched myself to get myself to bleed. Amazingly, it didn’t bring my period on. Then, after I did actually get my period, my best friend and I decided we wanted to be even more grown-up and try tampons. After a half-hour of frustration we gave up, shouting across separate toilets (she was a rich suburban girl with multiple bathrooms) “I don’t know which hole it’s supposed to go in!”

When I was a pre-teen, I stuffed tissue paper in my bra, so my then medium-size breasts would approximate Annette Funnicello’s impressive boobs. That was another embarrassing failure: “They’re spongy!” The boy trying to “feel me up” while dancing with me in someone’s basement shouted across the room to his friends. I never tried that enhancement again.

When I was Margaret’s age in the book—for me, that would be the very end of the fifties—we were a little more experimental and a lot less wholesome than Margaret and her friends. Maybe it had to do with being a city-kid. Maybe we were more influenced by television. Maybe our parents—many of whom were immigrants or first generation Americans and few of whom had any wealth—were less swept up in the post-war culture of scientific parenting and left us more to our own devices.

There was no Judy Blume to read. In fact, there was no such thing as “young adult” fiction. But there was “Little Women.” And then, advising an entirely different set of aspirations: Teen Magazines. And in just a few years, for those of us who wanted not to be “young ladies” any more but to be sexy cool girls, there was Joseph Heller and Alan Ginsberg and James Baldwin and Ken Kesey and Kurt Vonnegut and Norman Mailer. All men, their crises presented as serious and “deep”—while those of girls and women were regarded as “just about our little life.” “Domestic.” Sentimental. For someone like me, who had my brain and hormones (and ambitions) fired up by male writers but my heart still warmed by the March family, it was a warring mash-up of sexual and intellectual stimulation and longing to never lose the intimacy and tenderness and soft-heartedness of girl culture in my life. I wanted to cry over Beth’s death forever. The boys were scornful of that kind of thing, though.

After I saw the movie of “Are You There, God?” I read the book for the first time, and to be honest, liked the movie a lot more. The book was ground-breaking for decades but now seems stale (sorry, I know that will horrify Blume fans who see it as a “sacred text” but I’m guessing you’re mostly older than 30, and the book is a memory for you.) Written from Margaret’s point of view as a child living her life—not looking back—in the 1970’s, it logically doesn’t have much in the way of period detail (except for a few ancient rituals like “I must, I must, I must improve my bust”) or “perspective” on the period. Blume didn’t paint a picture of what the girls were wearing (other than no socks under loafers), what the furniture in their living room looked like, or what kind of dances they did in the basement. Margaret wasn’t describing her life to us, after all, but sharing how she felt with God. That unadorned quality contributed to the book’s longevity for a long while, allowing readers to fill in the particulars of their own experience.

In 2023, though, girls of Margaret’s age have Instagram accounts and know how to pose provocatively for them. Others are rejecting a feminine—or for some, any gender identity—entirely. And it’s hard to believe that gossip about letting boys “do things” “behind the A and P” makes a girl the school slut any more. Gerwig’s “Barbie,” whose heroine is a doll who is always changing her outfits and occupations to fit the times, pulled in audiences across the generations. But you couldn’t make Margaret into a contemporary preteen without losing the main narrative of childhood innocence colliding with the lure and mysteries of becoming a women. Is anything a mystery to adolescences any more?

It was smart of screenwriter Kelly Freeman Craig to not “update” the story to the present. (“It would be like updating the Bible,” producer James Brooks has said.) Paradoxically, putting Margaret’s life more squarely in its time and place is what refreshes it. Contemporary girls of Margaret’s age can laugh at the relics of “sanitary pads” and training bras while being reassured that secret anxieties—theirs even more tormenting than Margaret’s, because they aren’t supposed to have them—have always been a feature of growing up female. And those of us who did live through a less knowing time can have the pleasure of more precise recognition. My mother never took me bra-shopping, but I certainly remember saleswomen embarrassing me with recommendations for special “chubby” size clothes. And I love the ending of this scene. I take off my bra the moment I’m alone at home. Don’t you?

In the novel, too, Margaret’s mother and father have no personality. Except for the fact of their religious difference (her father is Jewish and her mom raised Catholic), which causes strife with the grandparents but is pretty abstract otherwise, they are just a generic mom and dad. In the movie, both of them are filled out with convincing detail: The father “looks” Jewish (but appealingly and non-stereotyped, not in the absurdly caricatured way in which Bradley Cooper is made to prosthetically embody Leonard Bernstein in “Maestro”) and he wears the ugly man-clothes of the era. The mother—like most of us in those days—is semi-sleepwalking through the role of wife and mom. And Craig has given her a substantial story-line that mirrors some of Blume’s own life. As Constance Grady writes:

“Blume’s Barbara is an artist who seems a little scattered in the suburbs and lightly on edge around her mother-in-law. Craig’s Barbara, in turn, is a bohemian who moves to the suburbs because she thinks it will be best for her child and then finds herself losing her own identity; who would like her mother-in-law to stop trying to raise her daughter for her now, please. In the film, Barbara becomes a stand-in of sorts for all the women who grew up on Judy Blume and are watching Craig’s film now as adults….All of it is consistent with the characterization Blume gave us, back when she wrote Margaret as a newly suburban housewife herself, writing books in between caring for her children. It’s just the stuff that Margaret, with the complacent solipsism of childhood, never bothers to lay out for us. She’s too busy trying to figure out how to be the version of herself Nancy and her parents and her grandparents want her to be — until she figures out how to be a version of herself that she likes instead.”

Judy Bloom approved: “It’s one of the ways I think the movie is better than the book. The book is internal, and if you’re a kid reading it, this is what you want to read about. You don’t want to read about your mother’s life. But when you’re watching a film, you need to know who Barbara Simon is. You never learn that in the book because it’s just Margaret’s point of view; she’s Mom. But she’s a real person, and Kelly made that happen.”

Although it’s impossible to credit a social or cultural movement in the conception and making of a film, Barbara’s new storyline was not only made to happen by Kelly Freeman Craig but by a feminist perspective on motherhood and female identity that was only on the verge of becoming in 1970. I don’t mean that the story has become “political” (it’s non-preachy and doesn’t look down on Barbara’s desire to be a good suburban wife and mom.) It’s rather that the mom has become more fully (as Blume puts its) “real.” We know things we didn’t know them, things that, were they avoided, would turn this charming film into an updated version of a fifties family sitcom.

Segue to Little Women, a film whose writer and director Greta Gerwig freely admits was inspired by feminist insight. She pitched her conception of the film as about “the ambition and the dreams that you have as a girl" and how they "get stomped out of you as you grow up"—a theme of Mary Pipher’s 1994 Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Lives of Adolescent Girls:

“Something dramatic happens to girls in early adolescence. Just as planes and ships disappear mysteriously into the Bermuda Triangle, so do the selves of girls go down in droves. They crash and burn in a social and developmental Bermuda Triangle. ..They lose their resiliency and optimism and become less curious and inclined to take risks. They lose their assertive, energetic and ‘tomboyish’ personalities and become more deferential, self-critical and depressed.”

You might think this is a modern insight that Louisa May Alcott couldn’t have intended as a theme of her novel. But in fact, it’s exactly what Jo March struggles with. Louisa May Alcott did too: at the age of thirteen, she wrote in her journal: "I have made a plan for my life, as I am in my teens and no more a child. I am old for my age, and don't care much for girls' things. People think I'm wild and queer, but Mother understands and helps me.”

Actually, all the sisters—with the exception of fragile, doomed Beth—have an abundance of vitality. There’s a lot of jumping, playing, hugging, and loud, unrepressed voices in the movie, and having not read the book in years, I wondered if Gerwig had gone too far with that. So I reread the book—and was reminded that I loved it not only for the heartbreak of Beth’s death or my identification with Jo the would-be-writer who wonders if its her fate to be lonely all her life, but the warmth and exuberance of family life depicted in it. And the irreplaceable intimacy of having sisters who you can joke with, fight with, put on plays with (I remember one with my sisters involving a “virgin sacrifice”), be furious with, resent, envy, love desperately and completely.

Alcott wrote that she meant her stories to be “jolly.” And I don’t think any other version of Little Women has captured that as well as Gerwig’s—so much so that none other than Chris Miller (director of “21 Jump Street” and “Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse”, and “The Lego Movie”) has said, “This is the most fun and most funny version of Little Women that I’ve ever seen…I remember just thinking about Little Women as a thing that is cold and dark, about sickness and people being shivering in a hole. And this movie is joyous and full of playfulness and dancing and running around on a beach and happiness. There’s obviously lots of drama in it, but it feels like a much more enjoyable experience than my vague recollections of the previous version.”

(I unfortunately couldn’t find a way to embed Gerwig’s fascinating narration of the “anatomy” of a scene that illustrates this, but click on this link and you’ll see how she did it.)

Gerwig ‘s Little Women (like Emma Thompson’s script for Sense and Sensibility) also foregrounds the economic context of her heroine’s lives. Most of the dialogue in the movie, while chronologically rearranged (the film goes back and forth in time, which the book does not) comes straight from the book. But one striking addition is a scene with Jo’s publisher, who (having been convinced by his daughters) has agreed to publish Little Women. In the scene, Jo haggles with him about advances, copyright, and royalty percentages. Some viewers might object that Gerwig is going too far outside the text here, but I saw it as an economical way of illustrating what Alcott has Jo saying many times in the book: writing (for both Jo and for Alcott) was not just about self-expression, it had to provide a living for any woman writer not born into or married to wealth.

For more of my thoughts on Little Women (and also Gerwig’s Barbie), see my earlier posts: Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Girl Culture and “Biggest Grossing Movie Directed By a Man.”

2.Tina Fey Turns Sociology of Girlhood Into “Mean Girls” (2004)

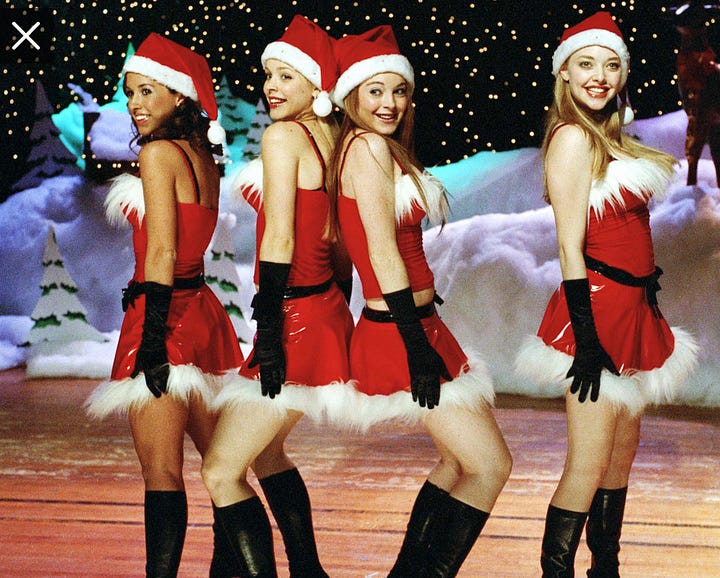

Mean Girls was directed by Mark Waters, written by Tina Fey, and starring Lindsay Lohan, Rachel McAdams, Lacey Chabert, Amanda Seyfried (in her film acting debut), Tim Meadows, Ana Gasteyer, Amy Poehler and Fey. The supporting cast includes Lizzy Caplan, Jonathan Bennett, Daniel Franzese and Neil Flynn. The screenplay is based in part on Rosalind Wiseman's 2002 book Queen Bees and Wannabes.

In 2002, a Newsweek cover article was called: “In Defense of Teen Girls.” “They’re not all ‘mean girls’ and ‘Ophelias’” was the subtitle. “Ophelia” referred to Mary Pipher’s thesis, which had such an impact on young Greta Gerwig. “Mean Girls” referred to a then-popular backlash against Pipher, protesting what was seen as “victim feminism.” Girls were not meek and mopey, persecuted and repressed Ophelias, sweet little souls with no defenses against a culture bent on domesticating them. No, they were as aggressive as boys, just in a different way. Girl-aggression, a spate of books argued, was “relational aggression.” With a greater value on intimacy, girls were experts at friendship. But because they knew so much about each other, they had viciously potent ammunition when they turned against each other. Which, as the new crop of books emphasized, they often do, through gossip, exclusions, and forming cliques.

“Margaret” illustrates this when boss-girl Nancy dictates the “no socks” rule for the “exclusive” club she invites Margaret to join, and encourages her three supplicants to gossip about Laura Danker, who is branded the class slut because her body is more sexually developed. (In fact, Laura is a good Catholic girl who goes to confession regularly.) But the no-socks rule is pretty benign compared to the behavior Rosalind Weisman chronicles in her 2002 book, Queen Bees and Wannabees. Girls are banished from lunch tables if they wear jeans on a Monday or ponytails more than once a week. They blackmail each other with shared secrets. They establish rigid hierarchies: “If you’re gonna be in high school, you have to stay in your place. A freshman girl cannot show up at a junior party; disgusting 14-year-old girls with their boobs in the air cannot show up at your party going ‘uh, hi, where’s the beer?” When Weisman, interviewing this girl, suggests a little compassion, the girl answers that she has absolutely no use for freshman girls; she doesn’t even know their names and why should she be expected to: “There are certain rules of the school system that have been set forth from time immemorial or whatever.”

Tina Fey is a genuine genius. She saw—in the spirit of “Heathers,” “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” and “Clueless”—that there was comedy gold to be mined here. She optioned Wiseman’s book, which was non-fiction sociology, and crafted a hilarious fiction, drawing on her own high-school experiences and her impressions of Evanston Township High School, on which the film's fictional "North Shore High School" is based.

As in “Margaret,” the film’s main character Cady starts out as innocent about the ways of girl world until she is recruited by Queen Bee Regina George (Rachel McAdams, whose character here is as imperious as her mom-role in “Margaret” is sweet) into her clique, known as “the plastics.” Cady’s seduction by the clique is less conflicted and more destructive than Margaret’s, but the narrative line is basically the same: she abandons old friends, acts like a twit, and after a revelation that she doesn’t like herself very much any more, comes around. But while Margaret’s clique is composed of 11-year-old, basically clueless little girls (even Queen Bee Nancy elicits our sympathy for lying about her period) “the plastics” are at the zenith of high-school popularity and know it.

Tina Fey (who also has a part in the movie) wrote the script, so it’s not surprising that it’s pee-in-your-pants hilarious. And full of actors (like Amanda Seyfried, in her film debut) that will go on to become familiar faces.

My favorite scene is below. Don’t stop after “Jingle Bell Rock” deconstructs. Go on to watch the rest of the clip, which includes the iconic slap-down of “fetch.”

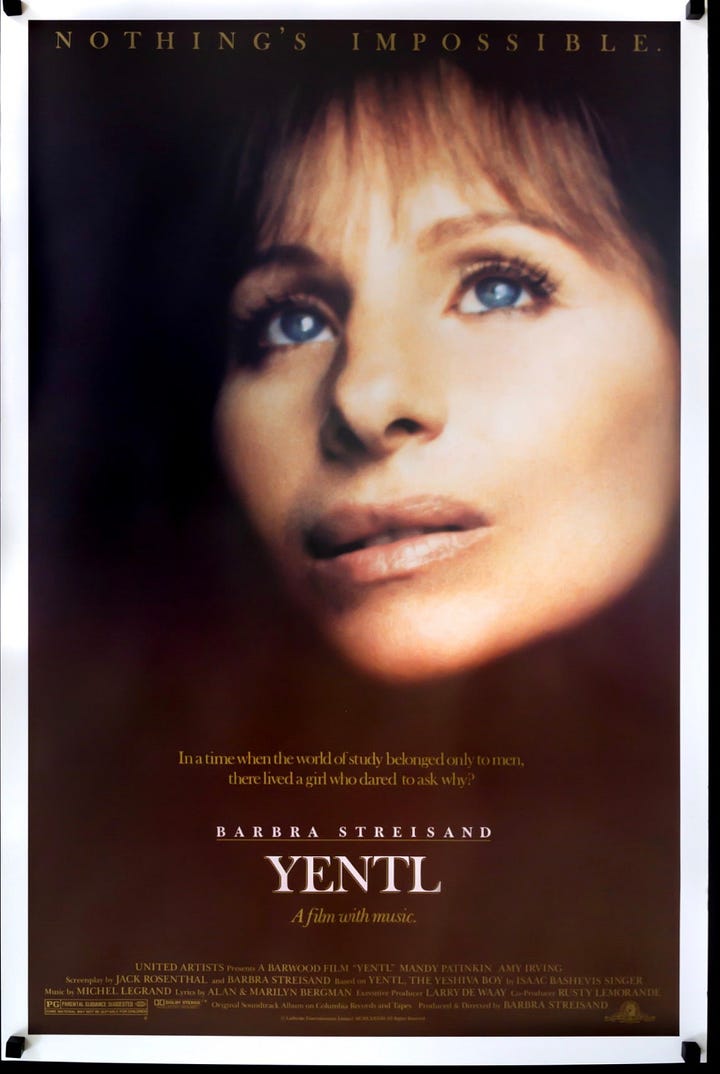

3.Under-rated and Ahead of Its Time: Yentl (1983)

Yentl was directed, co-written, co-produced by, and starring Barbra Streisand. It is based on Isaac Bashevis Singer's short story "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy". Stars Streisand, Mandy Patinkin, and Amy Irving.

“Yentl” was a passion-project for Streisand, and one she worked tirelessly to get made despite objections—from her then boyfriend and partner Jon Peters, from studios reluctant to back “an ethnic period piece with transvestite undertones,” and from Isaac Bashevis Singer himself, who wrote the first screenplay, but then backed out, believing that “Streisand’s age and celebrity would detract from the film.”

Peters also argued that Barbra was too “feminine” to play the role. He changed his mind after Barbra disguised herself and scared him into thinking the house had been broken into by a man. Age was still an issue, so Yentl/Anshul’s age was changed from 16 to 26, and with Singer no longer a part of the project, the script went through numerous rewrites by others, including Elaine May, Jack Rosenthal, and Streisand herself. The script would go through 20 variations before production began.

There was also pressure to make it a musical. But the last thing Streisand wanted was a “Sound of Music” spectacle in which characters ostentatiously break into song. People don’t stop their lives to sing, she argued. And keeping the narrative of a young woman who disguises herself as a man in order to study Torah was her central goal. The songs should not be “musical numbers” but integrated seamlessly in that narrative, and for the most part, the film succeeds at that (except for a jarring ending sequence in which Yentl, on board a ship to the United States, breaks into song like Fanny Brice singing “Don’t Rain on My Parade.”)

But watch instead what Streisand does in this scene:

It’s my favorite scene in the movie, and not only because the song is lovely. It’s one thing to masquerade as a man; it’s another thing to begin to inhabit the experience of a man, and through that change of location, to appreciate the loveliness of a woman—and one so unlike oneself, whose life is precisely the one Yentl has rejected for herself. Streisand could have made Hadass (Amy Irving) into a caricature of everything it is assumed (incorrectly, as are many notions about feminists) that a feminist would detest: the woman who lives to please a man. But in Streisand’s view here, the problem is not Hadass. (Who wouldn’t fall in love with her?) It’s a social order in which the loveliness of a Hadass is reserved exclusively for men’s pleasure. Which is also a social order in which Yentl doesn’t fit.

Later on in the film, after they are married, Yentl and Hadass do fall in love with each other. And while Hadass believes she has fallen in love with Anshel—a man—Yentl knows very well that the person she has come to love is a woman. “Where is it written?”—a refrain of a song and a theme of the movie—doesn’t just apply to the rules against a woman becoming a scholar. It also applies to a woman loving another woman. Avigdor (Mandy Patinkin), too, is drawn to Anshel beyond friendship even though he believes Anshel to be a boy. It confuses him (“Why do you keep grabbing me?” Yentl/Anshul asks him) and he had known the truth, it would have horrified him. But it’s there: the heart goes where it goes, it doesn’t obey “what is written.”

For a personal piece related to “Yentl,” see:

_________________

It’s Saturday morning and I’ve gone beyond the length that emails can accommodate and that I can expect you to enjoy (I often do.) I’m going to have to save “The Hours” and “Heartburn” for another time.

Have a lovely week-end! Susan.

Thanks for being here! If you like what you read on BordoLines, please subscribe! While I’m delighted to have you sign up for a paid subscription (and it’s a bargain), I cherish all my readers. A free subscription is fine!

Thanks for your thorough and well-thought-out assessments of these films... and the time travel through both life and movies.

I am 75, grew up in Silicon Valley. I have photos of myself in middle school, with teased flip hairdo. I carried hairspray to school. The first bra episode is very familiar. So, I was Gung ho to try.

However, what kind of parent takes their gradeschool girls to see the 1959 anti- nuke drama "On the Beach." Before that, they took us shopping for a bomb shelter, leaving with a car of bawling kiddies.

That movie stuck with me, underneath the flip dippity-do wannabe life...until I found an outlet. When I was freshman, dad and I saw a bearded guy near Cal Berkeley...with a sign. I asked about him. "He's a beatnik. And he's holding a peace sign. The symbol is from the signal Corp, spelling N D ... nuclear disarmament."

So I had a new identity. Had myself a pair of custom sandals made in North Beach. Bought a guitar and sang folk songs. Let my hair grow, not cutting it until after college.

Lucky for me, my parents let me volunteer nightly at the Palo Alto Community Theatre, where I enjoyed the company of Stanford intellects. Reading of plays...sarte, Beckett, brecht, Miller, Shakespeare. And I never drank until I was 21. And never became a hippie.

I really appreciate your series about these movies. I am enjoying filling in gaps I skipped over in my own life, the context. be it the more traditional "Little Women" or...how did I miss reading Virginia Wolfe? Well...all my authors were men.

Wonderful, insightful analyses, as usual, Susan. I still haven't seen Gerwig's 'Little Women'. I'd forgotten about it and now I'll have to look for it.

Two others about girls/women that might fit in here:

Dickinson (https://tv.apple.com/us/show/dickinson/umc.cmc.1ogyy5s2agasxa5qztabrlykn)

And 'Anne with an E'. It's a thoroughly modernized version of 'Anne of Green Gables', with more angst than the original, sexual ambiguity ,and all that entails. https://www.whats-on-netflix.com/news/introducing-netflix-original-series-anne-with-an-e/