“Maestro” Variations, Part 1: Bernstein’s Jewish Masculinity

Where’s the earthy, sexy mensch that both men and women fell in love with?

Prefatory Note: If you have the time, please watch the PBS “American Masters” Documentary “Leonard Bernstein: Reaching for the Note.” It’s on MAX, and you can also click here for a free copy.

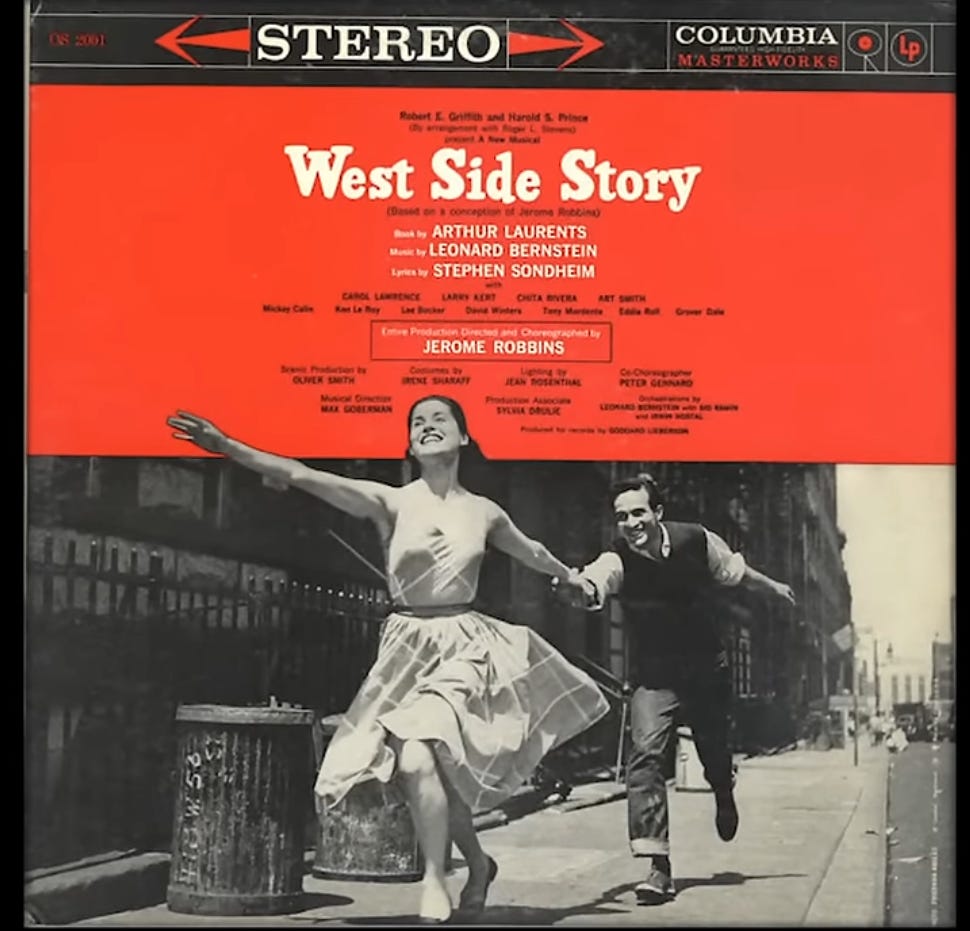

“West Side Story” lit something up inside me.

I was eleven, and Broadway tickets were cheap. When my salesman father wasn’t on the road and home on the weekend we’d often head out of Newark, through the tunnel, my sisters and I excitedly watching for the line that designates entry into New York. We’d see a show and have some Chinese food. I think that’s how I got to see the original broadway showing of “West Side Story,” but I can’t be sure, as I often also took the 107 bus into the city alone or with friends (we didn’t exactly have helicopter parents in those days.)

While I can’t be sure of those brain details, it’s not hard to bring back the feeling. I wasn’t a happy kid (too chubby, too sensitive, too ostentatiously liked by the teachers for my artwork and poetry) but I was determined that Susie Klein, at some point would be transformed and welcomed and my inner self and my life in the world would be in synch. Waiting, I got solace and the shape of my fantasies from movies, music, and Broadway shows. I saw a lot of them, and often stole the 45 boxed sets (easy to slip under my winter coat, and my parents were oblivious) of the ones I loved from the record store (remember when there were those?) so I could play the scores over and over. I got “My Fair Lady,” Harry Belafonte’s “Calypso” and “West Side Story” that way—and still can sing the lyrics to all of the songs.

There were a lot more stolen albums in my room, but those three were the ones that ignited my fantasies about men, women, and sex. Harry, because he was so dreamy, “My Fair Lady” because even then I was hooked on the challenge of achieving the love of a resistant man who had to be conquered. (The damage that particular fantasy did to generations of girls and women!) But it was “West Side Story” that got my body kicked into gear. The kinetic energy! The way those dancing bodies moved! The fact that Anita and Bernardo were unmistakenly having sex (“He’ll come in hot and tired. So what! Who cares if he’s tired, as long as he’s hot…”) And even Tony and Maria, after singing themselves into bed, woke up the next morning clearly having “done it.” Believe it or not, the whole audience gasped when the curtains opened on that scene—you just didn’t see that kind of thing in those days. (“The Music Man” won the Tony over “West Side Story”—enough said?)

And the bad boys! I had no interest in Tony; it was ‘Nardo that I wanted. For years, it was the bad boys in movies and in my classes that I fantasized about:

“February 22, 1962:

All in all, I’m not happy but am in a sort of unthinking existentialistic [sic] state and am pretty content. Especially since tonight is “Dr. Kildare” which really is pretty damn lousy and I think he looks like a girl, but I get some kind of sadistic pleasure out of seeing things being operated on. Give me “Ben Casey” anytime! He’s really a bitch, but he’s real rough and resembles a man at least! My taste in men (in the entertainment field) is really weird. I go from Marlon to Yves Montand to George Chakiris to Warren Beatty in two minutes. I hate Victor Mature, Bert Parks, Rory Calhoun, The Everly Brothers, Pat Boone, Eddie Fisher, etc.

The “etc.” contains the essence of what I was repelled by: referencing Claude Levi-Strauss, call it the “cooked” rather than the “raw.” (Marlon Brando: raw, especially in Streetcar Named Desire; Pat Boone: very, very “cooked.” Lassie: cooked; Rin-Tin-Tin: raw. Beatle John: raw; Beatle Paul: cooked.) My description of Joel (my real-life crush) bears out my preference for the raw: “He’s fast and moody, and he mumbles instead of talking and everyone thinks he’s ugly but I think he is adorable.” I liked boys whose gristle hadn’t yet been marinated by “gentlemanly” ideals. I liked boys who broke the rules.

I was 15 when I wrote that diary entry, and the “sixties” (culturally speaking) was just about to happen, but not quite yet. So in my early adolescence—it was to change when we all got rough and radicalized and sexually experimental about a year later—that eliminated most Jewish boys. They played the violin! They were hyper-literary (like me—and who wanted anyone who was like me!) And they were….um…Jewish! I wouldn’t say I was antisemitic, exactly. But I had internalized something about Jewish men that was akin to what many Jewish men then (think Philip Roth, who actually had gone to my high school a generation earlier) had internalized about blonde, blue-eyed, goyische women. The shiksa goddess had her male counterpart in my erotic imagination.

It was a form of self-hate, of course—taught to us by a culture that didn’t see Jews as worthy of being objects of desire.

By now you probably know where I’m going: Even before the counter-culture roughed up the Jewish boys I knew, Leonard Bernstein was changing my ideas about Jewish men. Bernstein, whose work and persona I began to follow after “West Side Story,” was my first Jewish crush (I may have had others that I didn’t know about; romantic icons didn’t advertise their Jewishness in those days, just the comics.)

He was gorgeous, of course—as beautiful as Harry Belafonte. But also, like Belafonte, with an earthy life-force that was, in Bernstein—wow!—very Jewish! So, so smart! So expressive! So sensitive! So much a hugger! And at the same time so masculine! (This has nothing to do with heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality, or transsexuality, as I hope readers already recognize, but I feel obliged to note.) I recognized in him the erudite, violin-playing boys I knew from school, but in Leonard Bernstein, forcefully, vibrantly divested of every (stupid! stupid!) stereotype I’d absorbed about Jewish men. (I’m not going to describe them here. They are antisemitic.)

Pauline Kael, who never obeyed the rules herself, describes what the Israeli actor Topol brings to the role of Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof” that Zero Mostel, on Broadway, did not:

“[Topol] is masculine, with burly, raw strength, but also sensual and warm, the way that other kinds of acting never are…..His brute vitality makes Tevye a force of nature-living proof of the power to endure…

…Perhaps because Topol is an Israeli, not an American Jew, he plays with a strength that is closer to peasant strength than to an American urban Jewish image…handsome, which is a blessing in movies, and, though bigger than life, he's still in the normal human range—his bigness is an intensification of normal emotions.”

Leonard Bernstein, of course, was as urban a Jew as one can get. And far more handsome than the “normal human range.” But there’s something in what Kael says about Topol that applies to Bernstein. Phrases resonate: “raw strength, but sensual and warm,” “force of nature,” “bigger than life” with a “bigness [that is] an intensification of normal emotions.”

If you watch the PBS documentary on Bernstein or listen to Stephen Sondheim’s recollections, or read his daughter Jamie’s autobiography or Jonathan Cott’s final interview with him (and loads of other resources), it’s very clear how profoundly Jewish culture—and identification with his own Jewishness, which sometimes embarrassed his more secular-minded children—was a part of who Bernstein was. His conversations were peppered with Yiddishisms and Jewish jokes and anecdotes, told with exactly the right accent and inflection—and uninhibited use of his hands. He didn’t need to learn how to do that; he grew up in a Jewish household. His musical compositions, according to professional musicians who know about such things, are full of Jewish musical strains and themes. When he played concerts in Israel—a nation that had his heart and that felt like home to him—he spoke fluently in both Hebrew and Yiddish to the Israelis, and they adored him.

He also taught the Vienna Philharmonic quite a bit about being Jewish:

“You know, in 1988 I took the orchestra to Israel—think of it: the Vienna Philharmonic!—and one of the works we played in Jerusalem was, in fact, Mahler’s Sixth. That was an experience! Imagine … this all-Catholic orchestra whose players, before I conducted them, didn’t know what a Jew was—musicians growing up in the birthplace of Freud, Schönberg, Wittgenstein, Karl Kraus … not to mention Mahler—a Vienna that had become a city with almost no Jews that was at one time the Jewish center of the world! “

When they asked him what “Kaddish” means:

“I said that it was related to the word sanctus, that what they said in church every week—sanctus, sanctus, sanctus—is the same word as kadosh, kadosh, kadosh. And they were turning white … and then one of the musicians stood up and said, Was meinen Sie, Meister? War der Christ Jüdische? ‘Are you telling us that Jesus was Jewish?’ Like innocent babies!… They didn’t know that Jesus was Jewish or that Jesus spoke a language called Aramaic or that in his time he was referred to as Rabbi Yeshua ben Yosef or that benedictus meant Baruch Haba B’Shem Adonai or that there was a connection between the Old and New Testaments. They were all churchgoing kids, well brought up in the traditions of their Nazi grandfathers. And yet I think of them as my dear children and brothers. People sometimes ask me how I can go to Vienna—Kurt Waldheim is the president of Austria!—and conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. Simply, it’s because I love the way they love music. And love does a lot of things.”

(From Dinner with Lenny: The Last Long Interview with Leonard Bernstein by Jonathan Cott)

Leonard was a scholar who knew almost as much about Judaism as his Talmudic ancestors, who were Hasidic rabbis. But as a mixed-religion family, the Bernstein’s “way of being Jewish” was more like that of my own. Jamie Bernstein:

“We loved our raucous Passover seder—closely followed by Mummy’s ingeniously devised Easter egg hunt. In December, we lit the Hanukkah candles for a few nights—but our attentions were soon diverted to decorating the Christmas tree. On Yom Kippur, Daddy and Alexander would go “shul-hopping” together, catching various cantors in assorted synagogues around Manhattan. One time, I was invited along on the shul-hopping. When we arrived at an Orthodox synagogue, the usher informed me that I had to go upstairs and sit with the other women. What? But—but I was with my father and my brother! Sorry: rules were rules. As I trudged up to the balcony, I thought to myself: That’s it. Count me out. Culturally, however, we were very Jewish: the Yiddish expressions, the music, the literature, the theater people—and the Life Jokes. That was the part of being Jewish that spoke to us; the religion part spoke to us less and less.”

None of that is even hinted at in “Maestro.” And while the movie isn’t a documentary—Bradley Cooper, in his interview with Stephen Spielberg, felt that would be a redundancy, given how much information about Bernstein’s life is already out there—there’s some amiss when a prosthetic “Jewish” nose (that wasn’t even needed, in my opinion, and only served to accentuate how much weaker Cooper’s jawline is from Bernstein’s strong profile) is seen as essential—but including a few Jewish-isms in his speech isn’t. I don’t object to the prosthesis by itself (his children didn’t, so why should I?) But I do wonder why a nose is made to stand alone for the Jewishness of a man who was so very Jewish. And it does make me wonder, too, if a Jewish actor—Jake Gyllenhaal, for example—might not have done better.

The ethnic vacuum is especially noticeable in the scenes of the younger Bernstein. Cooper simply doesn’t endow him with the solidity that Bernstein, even at 25, exhibited. Instead, he comes across as a giddy little boy of indeterminate ethnicity, who doesn’t even look very much like the breathtakingly handsome Bernstein of that era. (Funny, Cooper was once named “Sexiest Man of the Year” by People magazine, and I’ve found him very appealing in other movies. But I didn’t find him at all sexy in this movie—in which he was playing a famously sexy man!) It wasn’t until the aging Bernstein emerged, that make-up and a brilliant impersonation of Bernstein’s increasingly strangled, nasal sound (he had emphysema and a deviated septum) brought a feeling of the man’s actual physicality to the screen.

Some viewers have complained that Bernstein’s homosexuality wasn’t given enough attention in “Maestro”—and that may be true as well. But if that’s also true, it’s not because the length and depth of his relationship with Tommy was minimized—the film takes a lot of liberties with facts, which I’ll discuss in another “variation” on the movie, in a forthcoming substack—it’s because, as with the case with Bernstein’s Jewishness, it’s something that’s conveyed only through tropes: a slap on his lover’s butt, a wiggle when he’s dancing “On The Town” for Felicia (I did enjoy that one), a brushing away of Tommy’s hair from his forehead.

In real life, Leonard was deeply in love with Tommy, who brought out a part of his personality that was integral to him. Felicia (who I’ll write about more in my next stack), seeing that she wasn’t just “sharing” but replaced, told Leonard not to come back when he proposed that he spend a month of the summer with Tommy. Leonard did leave, and tried living an openly gay life. This was a period in Bernstein’s life not represented in the film except for a scarf around Lenny’s neck and a speech about living the rest of his life freely. Is that scarf as much as trope for this period in his life as the nose is for his Jewishness? In reality, he became much more “flamboyant” (as it was seen then) in his dress and behavior than just a scarf. From his daughter Jamie’s autobiography:

“My father came back from California sporting, of all things, a beard. I told Alexander I thought Daddy looked “like a Hasidic koala bear.” He moved into a suite in the Hotel Navarro on Central Park South, and Tommy Cothran was there with him much of the time. LB was madly in love, starting a new life—so he was cheerful, acting exuberantly gay and calling everyone “darling.” He’d even adopted my mother’s elegant white Aqua Filters, which elongated his every gesture into campy extravagance”

He couldn’t sustain it, not because he was ashamed of his sexuality or because Felicia’s cancer had recurred (that happened awhile after he returned home.) As his daughter Jamie saw it:

“But after spending several months in Palm Springs with Tommy Cothran that winter, LB apparently concluded that he couldn't make a life with him after all. They squabbled constantly; they had completely different living habits. They remained affectionately in touch, but they parted ways. I suspected that my father wasn't quite ready to adapt to life as an openly gay man. He was still considerably tethered to his middle-class immigrant upbringing, which prized assimilation above all; being openly gay sure didn't figure into that time-honored trajectory.”

Bernstein’s struggle, not about his sexuality (which I believe he embraced) but about how to create a life within which his sexuality could exist, without breaking his family, his Jewishness and his longing for the stability that assimilation into “American”, heterosexual norms afforded— these weren’t just biographical details left out in the interests of avoiding the replication of already documented facts. They were integral features of Leonard Bernstein’s personality, extraordinary appeal to other people (including Felicia) and, I believe, his ability to do the magical things for others that he was able to do with music.

A nose and a scarf don’t begin to do justice to it.

Coming up in my next stack: Lenny and Felicia.

Cited in this piece:

“

I saw Maestro. It was an okay movie. I found, as a writer, that it had the same major flaw that movies about writers have: Maestro didn't show the process of creating the music, of creating the art, the struggle and joy. I think of a story that Glenn Fry told about Jackson Browne. Years before they hit it big, Fry lived in an apartment above Browne. And he'd hear Browne working on songs. The piano, the experimentation with words in trying to find the right lyrics, and the humming of the melody when the words weren't there yet. And then Fry would hear Browne making tea. The rattle of the cup and spoon. The steaming kettle. And then the long silences, an hour or two, before Browne started working on the song again. Maestro captures none of Bernstein's process.

Bradley lacks the magical elixir that is chutzpah. I grew to disliked him as an actor after watching this.