This was a breakthrough piece for me. Trained as a philosopher, I’d learned to leave my personal life out of my writing. It’s astounding to me now that I wrote a book about women’s bodies and only mentioned my own struggles with weight once—and obliquely. But by the time I wrote my next book—on the male body—I was ready to break that rule.

My father had died in 1994, just as I was settling in to a new job at the University of Kentucky. My own body kept erupting in grief. Every hangnail or stuffed nose would turn into an infection, and driving the curvy country roads to school every day (we lived about 25 minutes away) I cried all the way, listening to Mandy Patinkin singing “I Dreamed a Dream.” I’d never seen “Les Miserables” (it wasn’t yet a movie) and had no idea what the song meant in the context of the play, but on its own it summed up my father’s life for me.

I was teaching a graduate course on the male body at the time. I liked to teach what I was working on in my writing (my students show up in nearly all my books) and one night, without any prior thought about it, I sat down and found myself writing “My Father’s Body.” Nothing that I’d written before had ever flowed so effortlessly; it just poured onto the page along with my tears.

I hadn’t imagined that I would put it in my book but after I shared it with my students I knew that I would. It became the book’s prologue, and The New York Times printed it along with the two reviews (one in the daily; one on Sunday) they published. They were wonderful reviews, both of them by men, something I’d wanted more than anything while writing the book—for men to respond warmly to a feminist book about them the way women had responded to Unbearable Weight. My agent emailed me “You’re a real writer now!” I felt like it, too.

Every Father’s Day, I repost it on Facebook. It’s not Father’s Day, but I want to share it with the people who have supported this new venture of mine. You’ve pulled me out of the writing-numbness of another, more recent grief and I’m so, so grateful.

My father was extremely private about his body. I never saw him naked, not once. To this day, I have no idea what his unclothed buttocks looked like, or his penis. I rarely saw him with his shirt off. Nor was he emotionally revealing, except when he was angry. His hugs, although expansive and affectionate, did not linger, seemed perfunctory. While he was still working, he was constantly on the move; after he retired, he was usually sunk in a private space, too depressed to connect. That shared malady, our dry skin, felt like intimacy.

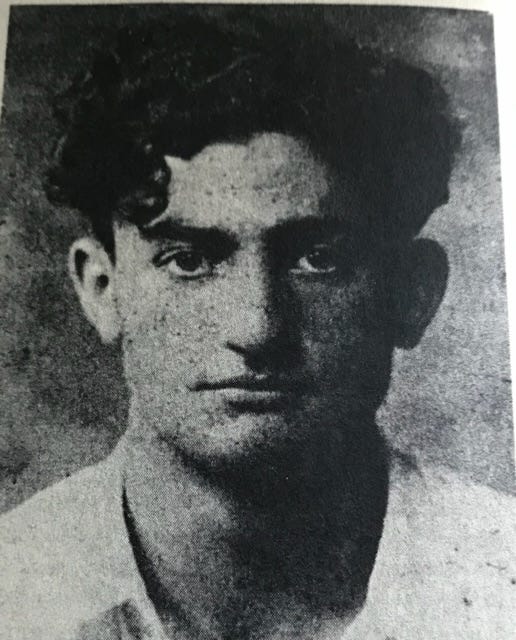

My father's body had three incarnations for me. The first belongs entirely to old photographs and stories of adventures that preceded my birth, photos which show my gather well built and dashing, as handsome as John Garfield, the tough Jewish street kid who became a Hollywood star. A trim and dashing young man stands beside a propeller plane; the strong eros he projects—his windswept pose, his jaunty sweater—is startling to me, even now that I know (as I did not as a child) that people can have several lives. In another photo, a sensual young man stares at me, his thick black hair and sultry, ethnic looks of the kind that are undeniably in vogue today. The girls of his Brooklyn neighborhood, lacking those cultural models, called him "the Jewish John Barrymore.”

During his Brooklyn youth, my father had been popular and successful. He was a track star and a straight-A student, but somehow managed—through his keen iconoclastic wit, feisty spirit, and willingness to take a dare—to win the respect and affection of members of the Jewish Mafia and their "dolls," with whom he hung out on occasion. I grew up hearing stories of his romantic exploits and brushes with danger.

Many years later, when my father retired, he committed some of those stories to poetry. "He lived in Brooklyn," he wrote, "but in spirit he dwelt in King Arthur's Court." "He dreamed when knighthood was in flower, And he would rescue every hour on the hour, The fair maiden from the dark and evil tower." My father's romanticism, however, was of the Damon Runyon variety. One of the maidens with whom he fell in love and whom he tried to rescue was gangster moll Alice:

A bobbed hair brunette, with bright violet eyes,

Alice looked out at the world with seeming surprise.

She was no ways naive, when you realize,

She was a child of the gutter, sharp, and streetwise

They sent her twice to the juvenile hall,

She escaped a second time, over the wall.

At eighteen, she was contracted by the Brooklyn mob,

Along with an accomplice, some underworld slob.

She would sit in a parked car, on the passenger's side,

While in the back, her partner would hide.

She would wink and flirt, with a male passerby,

Who would stop to inquire, with high hopes in his fly.

He succumbed to temptation and poked in his head,

And was promptly kayoed, by a pipe made of lead.

They rolled him expertly, and where he sought romance,

He was lucky indeed, if they left him his pants....

One day, Alice unfortunately tried her charms on a plainclothes policeman, and "got three to five." On release from jail, she met my father. The two "made love everywhere, despite the summer heat, always avoiding the cop on the beat." But the mob wanted Alice back in their ranks. Informed that they're coming for Alice at eight, my father orders a gun from "Ike, the Toad" and prepares for confrontation (just a bluff, he assured me, as I listened to the tale in childhood, rapt). When the "limo pulled up at the appointed time, inside it two hoodlums well-known to crime," the Toad still has not arrived. My father is beside himself, but determined to do the manly thing. "She stays where she is!" he declares. Suddenly, the Toad arrives, out of breath, and thrusts a crumpled kerchief into my father's hands. Inside it is the gun, in pieces, unassembled. The gangsters in the car, "laughing as if their sides would split, you'd think they were watching a vaudeville skit" (which my father was by now doing too, as he got to this part of the story), decide to leave my father and Alice alone. My father and Alice finally split up after one night when my father, who had taken Alice up on the tenement roof ("to rendezvous with blankets and whiskey, 100 proof"), falls asleep, then wakes up to see her walking along the edge of the roof stark naked. That's too much excitement, even for him.

Did these incidents actually happen? Told to me by a plump, balding forty-five-year-old, they belonged to a time and place as distant as Camelot, and as unavailable for factual confirmation. (My mother never disputed my father's accounts, but she never confirmed them either.) When men did "wrong" by his wife and daughters, however, my father's boyhood skills could resurface, offering their own kind of proof. An abusive gym teacher was told in no uncertain terms that if he called me "fatty" one more time he was going to have the shit kicked out of him. The summer after my first year at college—a year in which my main accomplishment was that I had "gone all the way" on my eighteenth birthday—I dared to close my bedroom door with a boy inside the room. He was the boy with whom I had celebrated my birthday, and my father had suspicions (which I subtly encouraged) that I had come home changed; he pounded on the door, threatening to break it down if we did not come out. These scenes left me confused about what I admired and wanted in a man. It was embarrassing for a modern girl to have her father behave like a caveman. But these were the proofs of love my father offered, and they had an archetypal resonance that I couldn't deny.

My father, who had thrived in his dual role of promising scholar and street-smart adventurer, was let down by the more sober, unromantic requirements of "good provider" manliness. The Depression forced him to abandon his dreams of college and a career in journalism; after the war, he returned from the South Pacific to a wife and small daughter (my older sister) and a job as a poorly paid employee of wealthier relatives, selling candy on the road for the family business. The job was not entirely unrewarding. He enjoyed making sales and loved traveling to exotic places like New Orleans, where he ate and drank in fancy restaurants, swapping stories with the pleasure-loving southern brokers who reveled in "Yosh's" warmth and wit. He'd send me postcards from the "Fabulous White Way" of the Las Vegas Strip; "Greetings from the land of lost wages, daughter!" he wrote on one in his distinctive, jaunty handwriting. But coming home from these trips was always to return to his subordinate status in the company, and what he increasingly came to experience as a failed life. He identified with Willy Loman.

This is the father that I knew through most of my growing-up life: the balding, large-bellied salesman with his sample cases and love of Chinese food, his generosity and intelligence like sunlight and his sudden dark furies. We three girls (and my mother) basked in the sunlight—the jokes, the stories, the trips away from Newark, into New York City—and cringed when the clouds came out. My mother seemed always to be waiting, smoking or dozing in my father's armchair, putting canned goods away, feeding the cat, until called upon to spring into action on his return. There would be tiny hotel soaps, plastic dolls dressed in buckskin, pecan pralines, restaurant matchbooks to add to my collection. The thrill of suitcases opening. Whisking away for Chinese food, to an air-conditioned restaurant. We were all in a good mood for perhaps a few hours; then, inevitably, came the crash. Usually, it began with a petty squabble, among the kids. Always, it escalated to something global, between our parents, and then metaphysical, between my father and God. "Why can't you ever ...?" "Why do I have to put up with ...?" "What did I do to deserve...?"

A photograph from this period in my father's life shows him at a table with three other men in business suits, presumably at a candy convention. There are ashtrays and a Heineken bottle on the white tablecloth. Someone must have been making a presentation; the three other men are smiling, one laughing. My father has his eyes closed, cigar in mouth, hands resting on the table, five fingertips of one hand touching the five fingertips of the other, almost as if he were in prayer. It looks like a composite photograph (although it isn't); my father's presence among the other salesmen is like a finger dislocated from the rest of a hand. I'd often seen him the same way at family gatherings, slightly apart, absorbed in some inner musings. My father of lost dreams, of the secret unlived life.

As the years passed, he became more brooding. He sought proofs of respect. Once, at age twenty-nine, I made the mistake of requesting that my father smoke his cigar outside the airless basement apartment I was living in as a graduate student. He blew up at me with a fury that surpassed the (considerable) furies I had witnessed throughout my childhood. Love me, love my cigar. My father sometimes said this jokingly, but we all knew he meant business. Rarely physically abusive, he could nonetheless be verbally vicious and frighteningly expressive. His eyes would darken and his mouth would set, almost in a snarl; often, he would leave rooms and houses, slamming the door behind him and managing to convey, with impressive believability, the possibility that he might never return. (He always did, later the same day or evening.)

As my father became progressively more frail and dependent on others, he became a "different man." At least, that was the way his second family—the children and grandchildren of my stepmother—experienced him. After he died, they were shocked and unbelieving to hear our stories of his petty tyrannies and temper tantrums. The man they knew was gentle "Grandpa Yosh," who loved children and didn't have a mean bone in his body. I think they believed that we, his feminist daughters, were remembering the past falsely through the screen of our own unresolved resentments and angers. But my father always had been sweet, there was never any question of that. He had been sweet, and he had also been armored, ready to be betrayed and treated without respect, ready for a fight as he had learned to be from his brawling father, from the screen heroes whom he adored, and from the minor gangsters he caroused with on the streets of Brooklyn. Ready to lay down the law and walk out the door when he was hurt rather than tell you how sad he felt, how sorry.

My mother had known this, long before I did. She forbade us to criticize my father's habits in any way. I saw this, not incorrectly, as an aspect of his dominance of our lives. When he sat down at the television to watch a baseball game, volume blaring, cigar smoke wafting across the room (or a wet, extinguished butt in the ashtray, sending off its acrid fumes), it seemed that he owned our collective space absolutely—unconsciously, yet absolutely. He owned the sights, and sounds, and (this was the worst, as far as my sisters and I were concerned, covertly grimacing at each other, our noses pinched between our fingers) the smells. Even today, I can't listen to the sounds of a televised sports event without feeling irritated, and vaguely queasy.

I wasn't wrong about my father's privilege in our household. But apart from the stories he told me, I knew very little, in those days, about the rest of my father's life. My mother did. She had known the streetwise, book-smart dazzler with bedroom eyes. She had known the young husband who sent long, romantic letters home from his ship, quoting Keats, Shelley, and Byron. She knew that my father's cigars were like pacifiers to him, portable reassurances that despite its many griefs and disappointments life could still be sweet and satisfying. She knew that when he yelled at us for complaining about the smoke, he was actually horrified at the thought that something he needed so badly might be disgusting to those around him. She knew that his seeming callous obliviousness in the face of our gagging throats and burning eyes was a defiant defense against his own deep shame.

My father's body as I knew it in my childhood was, on the surface, the very opposite of what was to reveal itself as my romantic ideal. Continually drawn later in life to tall, slender, aristocratic Protestants, I seemed to be fleeing, with a suspect desperation, everything my father was. But the surface of the body can mislead. The poise and politeness of my WASPs often kept them just as impenetrable and remote from me as my father's armor of Jewish affability and public largesse. And then, too, dotting my sexual landscape, there were always the other boys, the reckless, volatile ones with dark hair and sturdy legs. The first time I slept with a man whose body was solid, it was like discovering some deeply repressed but incontrovertible bodily need. I found his hands—the hands of a worker, a peasant (although he himself was a student of philosophy)—extremely moving. I savored looking at them the way I imagine men look at the cultural emblems of femininity, magnetized by meanings over which they have little control.

My father's last body is the one I was most intimate with. In his last weeks, his face became very thin, with sunken cheeks that brought out the Russian-Jewish structure of his face. He looked very little like the father I had known most of my life, more like an ancestral photo of a frail, aged relative from "the old country." I felt that his body was joining his mother's and father's, as my own body had been changing, joining his through resemblances that had been muted by a temporary and fragile individuation.

My relatives had warned me, as I got ready to drive down for what I knew would be a final visit, that his appearance might be shocking and upsetting to me. What I was not prepared for was the deep comfort—perhaps it could even be called pleasure—that I got from simply being alone with him, close to his body, from holding his hand or touching his shoulder as long as I wanted to, from looking at him with such an unobstructed intimacy of gaze, from lingering with him and over him. Exhausted, cocooned in a state of consciousness that was neither sleep nor waking, he mostly merely lay there, accepting my physical closeness, my caresses. Just once, he spoke to me. He told me he was cold, and he asked me to cover him. When I did, he thanked me with the grace of a courtier, in the affectionate male lingo of his RunyonesqueBrooklyn: "Thank you, doll. Thank you, doll." As wretched as he looked, I feasted on the sight of him as if he were my infant boy, and it was very hard to leave his side.

This piece originally appeared in The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private

Wow!! You are such a damn good writer, first off. Second: Have you read Winter Journal, the second-person memoir coming from the perspective of the body through decades, by Paul Auster? My guess is you have. I love your raw honesty in describing your father, what you have and haven’t seen. Beautiful. It makes me think of my own father, loving but clinically distant all my life. I remember seeing him naked smoking a Marlboro in the bathroom once when I was a boy, how it shocked me. We need more writers like you.

Michael Mohr

‘Sincere American Writing’

https://michaelmohr.substack.com/