My Favorite Fictional Killers and the Genius of the Actors Who Played Them

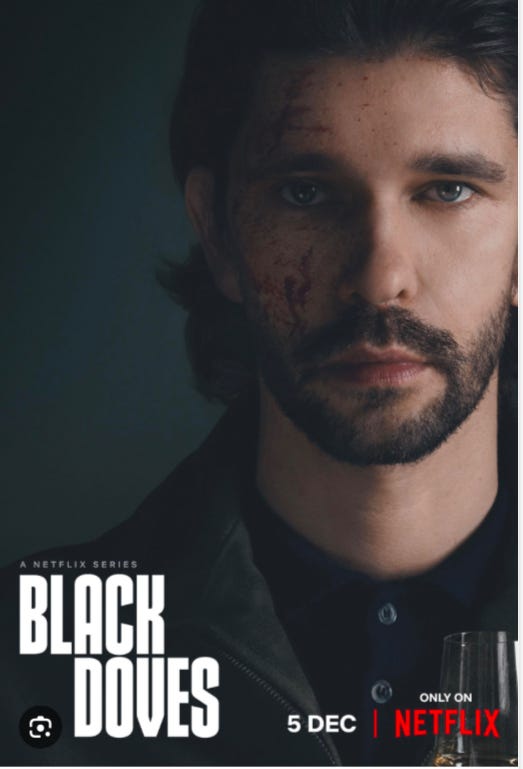

I’ve always been fascinated by compelling portrayals of killers in movies & tv. Too many to stuff into one stack. So in this stack I talk about 3 of my favs. Next week: “Black Doves,” darling!!

Villanelle (Jody Comer, “Killing Eve”)

Lovable serial killers are a rare breed. What we typically enjoy about these characters is the chill of pure evil, like Hannibal Lector, who savors a fine chianti and fava beans along with human body parts. Supposedly, actual (non-fictional) psychopaths can be quite charming when they want to be—it’s how they ensnare their victims—but it’s hard to think of a fictional psychopath who charms the viewer. Dexter, doesn’t count, as he has the redeeming feature of having been taught by his father to channel his psychopathy into killing only bad guys. The show never goes beyond good and evil; it’s about the struggle between good and evil.

Killing Eve did go beyond—everything: genre, recognizable politics, sexual stereotypes, conventional notions about love and sex, and even what counts as a fashionable outfit. Villanelle, the female assassin, may be evil—but she’s also whimsical, undefinable, and irresistible, and much of the pleasure of the show came simply from watching her: her ever-changing facial expressions (giggling or pouting like a five-year-old one moment, coldly eyeing her next victim in another), her clothing (sometimes fashionably butch, sometimes as pink and poufy as a little girl at a beauty pageant, other times like a little boy who couldn’t care less, sometimes simply bizarre), her unpredictable moves and moods.

It’s impossible to figure her out. Did she kill the boy in the hospital bed next to hers on impulse, possibly as an act of euthanasia, or simply to steal his stickers? Does she herself even know? Whatever; she looks far more fetching loping down the street, her tummy bulging out of his stolen Target boy sleepwear, than Ally McBeal did prancing around in her oversized pajamas with the little sheep on them. We can almost forgive the fact that she is a sadistic murderer because she gives us so much pleasure with her fashion choices, and they give her so much pleasure, too. (She is barely able to force herself to wear a nurse’s dowdy slippers, in order to escape from the hospital.)

Eve isn’t a natural-born killer, but she’s weird, too. It’s fairly easy to understand the magnetic pull Villanelle exerts over her; she discovers that she needs doses of danger to keep her heart going. But what’s the nature of Villanelle’s attraction to Eve? It’s sexual but not primarily, it’s not about Eve’s great, big hair (which Villanelle does love), and it’s not just admiration—although it’s clear Villanelle does admire something in Eve that other people lack. But what is it? Villanelle may be a trickster, but Eve is just . . . unfathomable. She seems normal in many ways, but it’s a foggy sort of normal, a walking sleep that only Villanelle is able to wake her out of. And even when awake, she seems not to know what she’s doing with herself half the time, even as she has an instinctive brilliance for investigation. Eve and Villanelle seem to be in love with each other (which causes them to “do crazy things”—as Villanelle says—like try to kill each other) but to make those words “in love” apply, they need to be reinvested with something that isn’t within my vocabulary—and certainly isn’t found in the conventions of romantic/sexual relationships, depicted in movies and TV, even the kinkier ones.

Some reviewers have tried to slot Killing Eve within recognizable, if transgressive, categories: Melanie McFarland, in Salon, describes it as a “feminist thriller” for the era of #MeToo, that “slakes one’s desire to see piggish misogynists get what’s coming to them” by having them dispatched cold-bloodedly by the disarmingly pretty and seductive Villanelle while complicating the simplicity of sisterhood by making her as dangerous to the woman she’s irresistibly drawn to—Eve—as to the men she disdains. Along those lines, Willa Paskin in Slate writes that the show warns the viewer that underestimating women is dangerous. They may appear, as Villanelle frequently does, as hyperfeminine; but her hairpin is a deadly weapon.

But Villanelle isn’t your typical femme fatale. Her emotional life is more like that of a child. She likes to play, to goof around. She is drawn to toys, then throws them away carelessly. At one point, after murdering an infant’s mother, she picks up the baby and seems to take genuine delight in playing with it. But she soon tires of it, is annoyed by its crying, and when her old mentor Dasha (Harriet Walker) dumps the baby in a nearby trash can, indifferently walks away.

The scene is both shocking and darkly funny and reprises a similar sequence of events that takes place when we are first introduced to Villanelle, in an outdoor café, where she is staring at a little girl eating ice cream and smiling at her mother. Wanting to catch the little girl’s attention, Villanelle works at copying her smile, and it isn’t clear whether this is someone with an absence of human emotion trying to fake it or she’s just awkwardly being friendly. The little girl is wary at first—why is this stranger smiling at me?—but eventually smiles back and is rewarded by having her ice cream dumped onto her dress. The scene is a perfect introduction for a character who will always keep us off balance, and a feminist message seems forced and irrelevant to either her, Eve, or their relationship with each other. They are profoundly strange people, the show is “hilarious, bloody, [and] unclassifiable,” and it’s enough that it’s so enjoyable to watch.

Tommy Lee Royce (James Norton, “Happy Valley”)

Every superhero deserves a super-nemesis. Tommy Lee Royce (James Norton), a drug dealer/rapist/murderer whose rape of Catherine Cawood’s (Sarah Lancashire) daughter Becky left her pregnant and suicidal, is the most compelling psychopath since Villanelle. Like Villanelle, Tommy is disarmingly gorgeous. Unlike Villanelle, he has no playful side. For most of the three seasons, he doesn’t even seem to have a human side. The trail of human damage he leaves is matched only by Catherine’s righteous fury, which gripped her since season one, and which is a thread that links all the seasons together.

Catherine nurtures her hatred. She cannot—will not—forget that after Ryan (Rhys Connah) is born, Becky does kill herself, and she finds it “unfathomable” that anyone would see Royce as anything but the lowest form of scum. As far as Catherine is concerned, Royce has rescinded all claim to human understanding, and as she raises Ryan, she’s both anxious over the possibility that Ryan may have inherited some of Royce’s tendencies, and determined (without success) to keep him out of Ryan’s life.

I’m not sure why James Norton was chosen for the role of Tommy Lee Royce, but it was a brilliant choice. Audiences were getting to know him (and many falling in love with him) in Grantchester as the adorably sexy vicar everyone in the village wants to lead into sin. Tommy Lee Royce, capable of running his car back and forth over the broken body of a young policewoman, raping a gagged and terrified kidnap victim, and pouring gasoline over his own son with the deranged fantasy of setting them on fire together, is so far from Sydney Chamberlin that despite Norton’s distinctive good looks, many viewers had to ask if this was the same actor. (This season, Royce, whose hair and beard had grown long and Rasputin-like in prison, gets a haircut; when I posted a clip, one of my facebook friends exclaimed “Oh! There’s Sydney Chamberlin!”)

That’s a testament to Norton’s acting. But for those of us who recognized Sydney, our lingering affection for the vicar—not to mention how gorgeous Norton is—also makes Royce a much creepier adversary. It makes it harder not to feel a tug of attraction for him, and that’s a far more insidious effect than a villain whose exterior is as repulsive as his evil inner life. Watching him get that haircut was almost like a strip-tease—which the show unabashedly exploited, showing us the whole thing from first swath cut by the electric razor to a bare-chested Royce preening in front of the mirror.

For Catherine, though, he’s simply the incarnation of pure evil, and she can’t even stomach the possibility that her daughter might have been attracted to him at some point (which of course doesn’t preclude the fact that he raped her.) But then, in the finale, when they finally come face to face, he says some things that insert a little bit of mystery into the Tommy/Becky backstory that we’ve only been told about from Catherine’s point of view:

Tommy: I loved her. I loved her!

She made me feel normal.

And then she didn't want to know me, and that's when I got cross.

And that was you.

Catherine: Well, I don't know what you're talking about.

Did Royce love Becky? After the final episode, we’re not so sure anymore. Does he love his son Ryan? We’re not so clear on that any more either. He tells Catherine:

I had some options last night.I had a can of petrol and a box of matches,

and it did occur to me that I could burn your house down and all the shit in it,but I decided not to do that.And do you know why?

Next time you're thinking all this nasty bollocks about me, I were looking at them pictures of Becky...and Ryan. His whole life, from when he were a baby.

All them years I never even knew him.And do you know what I realised?

I realised...I realised what a nice life he's had.What a nice life YOU'VE given him.

I hated you.I hated you for not telling me I had a boy. But last night, I had a glimpse of what a nice life he's had. And I don't hate you anymore.

He then douses himself with gasoline, and warns Catherine that if she tasers him it might spark him off and she might get killed as well, and continues:

Believe it or not....I don't want you

to get done, you deaf bitch! I want you to be here...with Ryan.

So I'll do it me self.

And he sets himself ablaze, screaming.

“Happy Valley” is perhaps the greatest British procedural of the past ten years (and the seasons do roughly span that time period.) It’s Sally Wainwright’s writing, it’s Sarah Lancashire’s acting. And it’s the fact that Tommy Lee Royce is not the shadowy, impersonal presence that exists in many thrillers largely to be the object of pursuit. That last, protracted conversation between the two of them is so exactly right. Some viewers might wonder why Catherine indulged him—and herself—rather than just tasing him straight off. But that would be have been a betrayal of Catherine, and of us, too, having invested so much in getting to this final confrontation. They each needed to speak their truth to each other—and it’s not exactly as neat as a fatal bullet. Tommy doesn’t become less of a psychopath in our eyes. But he does reveal, as other characters have throughout the series, that nothing is pure, not even evil.

(In England, James Norton’s Tommy Lee Royce was voted the best villain on TV, winning the title overJodie Comer as Villanelle in Killing Eve (who will always be my favorite psychopath), JR Ewing in Dallas (Is that still airing?), Sherlock Holmes’ nemesis Moriarty and Coronation Street serial killer Richard Hillman.)

Tom Ripley (Andrew Scott, “Ripley”)

Andrew Scott is not the first actor to play Tom Ripley. But he is the first to play a Ripley who is true to Patricia Highsmith’s book.

Clemente’s 1960 Purple Noon, the only Ripley movie Highsmith lived to see, is very French “New Wave.” Starring the astonishingly pretty, young Alain Delon— who nowadays would more likely be cast as Dickie Greenleaf—both Ripley and Dickie exist in an (heterosexual) existentialist playground, pretty much doing anything they please. Except for Dickie’s wealth and macho confidence, there’s not that much “moral” difference between the two.

Anthony Minghella’s version (The Talented Mr. Ripley,) made at a time when film-makers were coming out of the “celluloid closet,” made Tom’s (Matt Damon) homoerotic attraction to Dickie (Jude Law) explicit, but also turned Tom into an incurably hopeful puppy-dog who will take anything Dickie has to dish out, no matter how hurtful, so long as he isn’t left on the side of the curb. John Malkovitch’s Ripley (based on a later Ripley book, “Ripley’s Game”) is, as you might expect, tremendously seductive and smooth. He’s also sweetly attentive to his wife, and may even have something of a moral compass.

Given these portrayals, it’s not surprising how often Ripley is described in reviews as a “charming” psychopath. “Highsmith’s most alluring sociopath” Sam Jordison wrote in The Guardian; “It is near impossible, I would say, not to root for Tom Ripley. Not to like him. Not, on some level, to want him to win.” He enumerates the reasons why:

It’s a classic story of someone who starts off down on his luck and disregarded, but who, through force of personality, hard work and sheer determination, manages to make something of himself. He’s had a hard upbringing. He lost his parents and was brought up by an aunt who called him a “sissy”. And yet, he came out the other end polite, self-effacing, hard working. He is endearingly shy in company and worried about the impression he makes on others. He is always assessing himself, always trying to improve.

He is also endearingly starry-eyed…and he never loses [a] charmingly naive appreciation of good fortune and high society.

In fact, however, there’s nothing “charming” about Highsmith’s Ripley. Yes, he can be amusing—when he wants to ingratiate himself with someone who can provide benefit to him. More often, he’s irritated by people (like Humbert Humbert, he’s especially disgusted by heavy-bottomed women, which Marge is in the book, but—of course—not in any of the films.) Yes, he is very, very clever, but his talents are those of an escape artist who does what he perceives as necessary, and often it involves dealing with a dead body in ways that are graceless and bumbling. There’s nothing “starry-eyed” about him; he’s ruthlessly pragmatic and opportunistic. He’s not “endearingly shy” so much as emotionally detached. And yes, he’s always “assessing himself”—but not in order “to improve,” in order to perfect his various “performances.” Here he is, on the ship en route to Italy:

“He began to play a role on the ship, that of a serious young man with a serious job ahead of him. He was courteous, poised, civilized, and preoccupied. He had a sudden whim for a cap and bought one in the haberdashery, a conservative bluish-gray cap of soft English wool. He could pull its visor down over nearly his whole face when he wanted to nap in his deck chair, or wanted to look as if he were napping. A cap was the most versatile of headgears, he thought, and he wondered why he had never thought of wearing one before? He could look like a country gentleman, a thug, an Englishman, a Frenchman, or a plain American eccentric, depending on how he wore it. Tom amused himself with it in his room in front of the mirror. He had always thought he had the world’s dullest face, a thoroughly forgettable face with a look of docility that he could not understand, and a look also of vague fright that he had never been able to erase. A real conformist’s face, he thought. The cap changed all that. It gave him a country air, Greenwich, Connecticut, country. Now he was a young man with a private income, not long out of Princeton, perhaps. He bought a pipe to go with the cap.”

The Ripley movies are entertaining and artful movies in their own right. They also are windows onto the different artistic cultures of 1960 and 1999 respectively—one enchanted by anti-bourgeois rebellion, but paradigmatically of a strictly white male, heterosexual variety, the other unwilling to keep homosexual love in the celluloid closet any more. But it’s only with Steven Zaillian’s Ripley and Andrew Scott’s perfect performance that, in my opinion, we finally get Ripley as Patricia Highsmith imagined him (and identified with him: she sometimes signed her letters “Tom/Pat”.) We’re more than ready for him, in this culture of ours in which performance and “optics” count for more than character, compassion, and integrity, in which half of the population and an entire political party has been bamboozled by a highly skilled con-man—who, like Ripley, also manages to maneuver his way out of accountability for every crime he commits.

There are so many ways in which the series is spectacular I could easily spend a separate stack reviewing it. But there are lots of such reviews around, and my interest, in this particular stack, is on Tom Ridley and how Zaillian/Scott have creatively revisioned him, ironically by returning to the original text and virtually enacting it—including the drawn-out, arduous post-murder struggles with the dead bodies. (My husband couldn’t take it, and mid-way through the sequence he went to bed.) Except for a few artsy inventions (e.g. the parallels with Caravaggio, who Tom is mesmerized by), the preponderance of steep stairs (which Dickie and Marge navigate with ease—a symbol of their confident physicality and unconscious privilege—while Tom huffs and puffs), and the continued (mis)representation of Dickie (Johnny Flynn) and Marge (Dakota Fanning) as lovers (in the novel, the relationship is more complicated), most of what happens comes straight from the book, and very little has been left out. It’s a luxury an eight-episode series has that a 90-minute film doesn’t have. But the courage of Andrew Scott’s performance, in which he deliberately resisted the influence of earlier versions or the critics’ assessments of them, was the crucial ingredient. “You don’t play the opinions, the previous attitudes that people might have about Tom Ripley,” he told Vanity Fair. “You have to throw all those out, try not to listen to them, and go, Okay, well, I have to have the courage to create our own vision and my own understanding of the character.”

Courage was required because the Tom Ridley of the novel is not a colorful, fascinatingly evil killer but a vacant, uncertain, inexpressive black hole of a person who psyches out and performs whatever qualities are required by the situations he finds himself in. Unlike the famously ghoulish serial killers who eat the body-parts of their victims to possess them, Tom only feels “full” when he swallows the “not-him” that he desires, not by physically digesting him but by embodying him. Most of the time he’s glum and vaguely annoyed with himself and other people. His moments of pure pleasure only come in the novel after he has “become” Dickie, and can enjoy, not only the material delights of wealth, but the social status it brings.

As Dickie, Tom smiles at the concierges at the hotels and they, as is their habit with the presumed monied, smile back and offer to serve him in any way. Of course, as soon as Tom’s back is turned, their mask of subservience falls off, just as Tom’s does when his own performance is failing. And because he is continually facing the threat of the increasingly elaborate web he’s woven coming apart, that’s pretty often. He’s thus not a very vivacious character to play. And remarkably—this is “hot” Andrew Scott, after all, and the cinematographer had some work to do—he isn’t even physically very appealing. (In the book, he describes himself as merely “ordinary.”)

Some reviewers have been put off by the “new” Ripley. One wrote Scott’s performance off as “bland and uncharming.” Another: “Previous projects have presented a more inviting experience in which the audience becomes enamored of Tom’s treacherous designs. Here, over eight tepid episodes, he never undergoes any fundamental transformation. From the beginning, he is just a grating grifter who lacks finesse.” That’s the risk Scott took in playing Highsmith’s Ripley (as opposed to the mythology of the charming psychopath.) Highsmith’s Ripley is not “charming.” That requires some ease of being, and Tom is trapped in the stiff cage of his uneasy consciousness. He’s empty rather than evil—which gives more sense to his hunger to be filled by Dickie and Marge as personalities and social beings than chunks of flesh served up with a good Chianti. And it resists categorization in any standard psychiatric diagnoses, an ultimate undecipherability that Scott deliberately went for: “The big challenge of it,” he’s said, “was that there’s a kind of unknowableness to the character that I think you have to acknowledge. Once you acknowledge that, you’re not trying to diagnose him with anything that might actually reduce the very thing that we’re interested in.”

It’s an amazingly restrained performance. He walks and talks like an actual human being and also does a lot of awful things but without much change of expression. Sometimes he smirks a bit, when he’s getting even or exercising power over someone he resents or has humiliated him. Sometimes he gets transfixed (e.g. looking at the Caravaggio of David and Goliath or watching a sinuous, seductive singer in a bar) but it’s only his eyes that register his transport—eyes that most of the time are glazed, staring, creepily photographed reflecting a dead, white center of nothingness. No window onto the soul. He only becomes fully expressive when he’s angry—as, for example, when being baited by the detective Ravini (Mauricio Lombardi). His resting face is worried, his mouth drawn. Most of the time he acts out of necessity rather than feeling; he even embraces Freddie’s dead body and kisses his lips when a passerby sees him with his arm around Freddie. It’s a dead and bloody body—and Tom isn’t a necrophiliac. It made me squirm. But Tom is used to do what he has to do to survive.

Tom’s great “talent” is not the ability to ensnare and deceive people with charm (he doesn’t often succeed at that, and frequently rouses suspicion—in Marge and Freddie, for example, not to mention the ever-watchful cat at his Rome apartment building) but (as the Malkovich Ripley describes himself) as a “gifted improviser” who is always able to maneuver his way out of trouble when his performances stumble and the lies collide with each other. He is able to do that because he has no conscience to interfere; just an unswerving priority on self-survival. He does whatever is necessary to preserve and protect himself.

It’s disturbing familiar, isn’t it? Our own soul-less grifter also has a an unswerving instinct for self-preservation at all costs. He has maneuvered (without much trouble, because their own moral centers were already fairly vacated when he entered the scene) an entire political party to follow him. He’s snookered ordinary people into believing he cares about them, when in fact they are entirely dispensable the moment they stopping serving his needs. Journalists and psychologists have tried to figure him out. But none of the theories work, because they all presume a substance (a personality, a soul, an enduring set of principles or commitments, a human constancy of any kind at all) that simply isn’t there. In its place is a series of inventions and reinventions to suit the necessities of the moment. And unlike Tom Ripley, he’s pulled the con off straight back into the White House.

[This section is based on material from an earlier stack. In it I go into more detail about the movies and the series. If you’re interested:

Next week:

My favorite Ripley is Andrew Scott, he is always so smarmingly cheeky, with a drawling, crawling, voice.

I loved watching Killing Eve. The two stellar actresses played off each other like punctuated windchimes. Sandra Oh displayed complicated emotional ties with savage intensity. Jodie Comer as Villanelle was fascinating. You hate her cruelty, you love her excessive quirkiness. And her outfits! The pink floofy dress she wore to her possible "dressing down" was perfect. I wanted one just like it. Fiona Shaw was brilliant as well. Excellent show and acting, with very strong women characters.

Always love reading your deep takes on TV and movies.