O.J. Simpson: A Few Things That Didn’t Make Yesterday’s Headlines

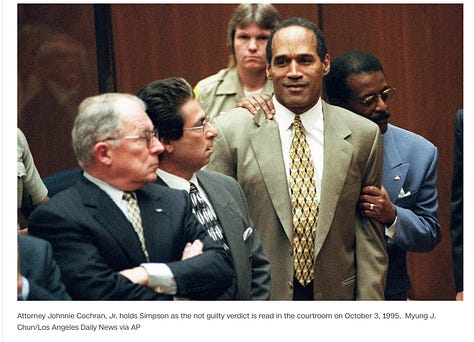

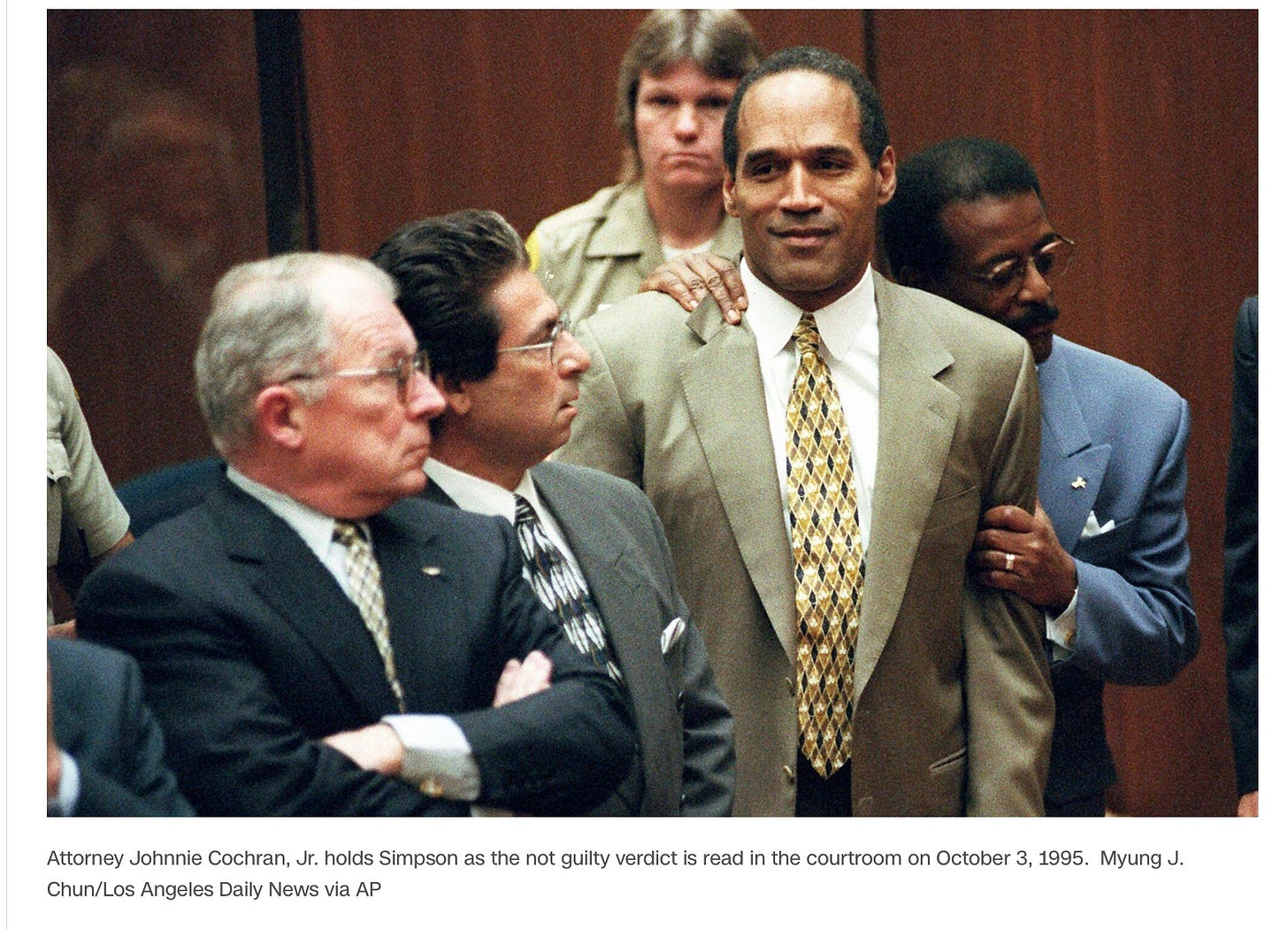

This morning I listened to the crew at “Morning Joe” reminisce about the O. J. Simpson trial. They enjoyed schmoozing about how the trial changed the media and people’s viewing habits. Elsewhere yesterday, I saw O.J.’s now-undisputed murders of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman become one event in a series of “retrospectives” on his career. Many of the headlines referred to “accusations” or “acquittal,” leaving those who weren’t grown-ups during that year with the impression of his innocence. The picture of Johnny Cochran embracing a relieved Simpson was the mainstay of imagery from the trial. The mainstream media writes history through headlines and images; now yet another chapter will get blurred.

The media only mentioned in passing the painful racial division that the verdict generated. One of my good friends, at the time, was one of the few Black female faculty members at the Jesuit college I taught at. We never talked about Simpson, but I knew how she felt. When I heard her knocking on my office door after the verdict came down, I couldn’t bring myself to open the door. I was furious and I knew she was pleased at the verdict. We had stood together on so many aspects of racism and sexism, but this was a bridge we couldn’t cross. I’m certain we’d be able to have a conversation about it today. But then, I just wanted to avoid a collision of our perspectives.

The mainstream media of course didn’t discuss how pivotal the televised trial was as a key moment in the cultural dissolution of respect for fact, and the increasing dominance of repeated “narrative” and attention-grabbing “optics.”

Daniel Boorstin, with great prescience in 1960, had coined the term “pseudo-event”: reality configured and packaged for the viewer, reality transformed into a contrived image with is “more vivid, more attractive, more impressive, and more persuasive than reality itself.” In 1960, Boorstin seemed alarmist. But by the time I taught my “TV Culture” course during the Simpson trial, the pseudo-event had become the coin of the realm—and not just on television. When computerized images first began to replace “air-brushing” we were shocked to learn how much digital alteration was seeping into the creation of magazine imagery. By 2009, Adobe photoshop had begun to market its digital software with the incitement to “Spread Lies” (remove those wrinkles, love handles, dog drool) in your photos. And today, 12-year-olds post glamour-shots on Instagram as artfully retouched and transforming as the covers of Vogue.

Before the verdict, I asked my undergraduate students what they thought about Simpson’s guilt or innocence. “Oh, he’s innocent!” said one (who happened to be a young white man). “On what basis have you come to that conclusion?” I asked. “Well . . . I don’t know . . . he’s a football hero, and handsome, and seems nice and friendly, and, well . . . I just sort of see it that way.” When I pressed him further he just kept repeating: “I just sort of see it that way.”

“I just sorta see it that way”: that argument was many of the jurists’ justifications for their verdicts, too. Detective Philip Vannater, one explained, didn’t look jurors in the eyes and thus couldn’t be trusted. But criminologist Henry Lee’s warm smile (“Henry Lee was just so likeable”) made him a thoroughly dependable witness. But the most anti-fact, pro-“just sorta seeing it” explanation of all: one of the jurors, questioned after the verdict about the DNA evidence, shrugged it off: “To me, the DNA was just a long string of numbers . . . it was just a waste of time. It was way out there and carried absolutely no weight with me.”[i] DNA as something one could accept or reject? By 2020, the dismissal of science via climate-change deniers and creationists may be familiar stuff. In 1994, however, it was shocking to me.

The Simpson trial, in my personal history of watershed moments of television’s contribution to the decline of fact, is way up there. I watched it all. My husband and I had just moved to Kentucky, our new home was in the country, and initially we only had a few channels, one of which was Court Television, which had launched in 1991. We became addicted, mesmerized by how defense lawyers, aided and abetted by the sympathies and susceptibilities of jurors, were able to construct an alternative reality to counter the massive factual evidence that Simpson killed Nicole and Ron Goldman.

Perhaps there was nothing especially new there in terms of lawyerly strategy. But televised gavel to gavel, it became available for all to see. (Court TV presented seven hundred hours; CNN six hundred. When the verdict was announced on October 3, 1995, it was covered live on every major network and drew an estimated 150 million viewers.) The lawyers themselves were open about what they were doing. Simpson defense lawyer Barry Scheck, for example: “What people really do,” he told Lawrence Schiller, “is listen to testimony and turn it into a story that makes sense to them . . . the key is to get the jurors to integrate all the information into your story line.” As the defense team planned their strategy, Scheck wrote on a blackboard the story that he believed would be most compelling: “Integrity of the Evidence: Contaminated, Compromised and Corrupted.”[ii] Once that story was made real for the jurors, it would make little difference that even if one threw out all the evidence that defense claimed was contaminated and compromised, one would still be left with more than enough evidence to convict Simpson. The narrative, repeated over and over, won the day and relieved jurors of the responsibility to actually go through the evidence, sifting and weighing the relative strengths of each piece.

I leave you to think about how a similar strategy has become the (perhaps unconscious) rule for media “story-telling.” Plaster pictures of a horribly decimated Palestine without accompanying history or context. Continue to give Donald Trump all the prominence he craves; let every fresh lie stand on equal footing with the evidence of his chronic deception. Allow repetition to take the place of responsibility to fact, history, truth.

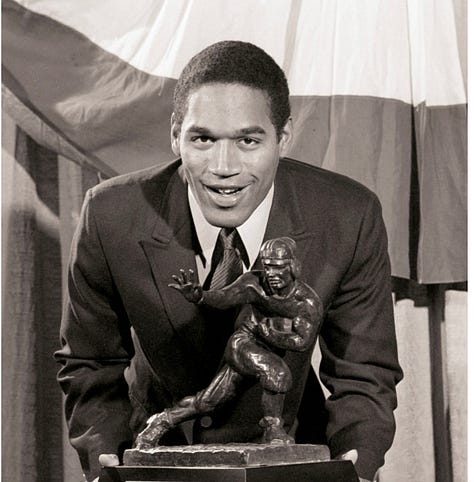

Who was O.J Simpson? What impression would you be left with from yesterday’s headlines and images?

[i] Sheila Jasanoff, “The Eye of Everyman: Witnessing DNA in the Simpson Trial,” Social Studies of Science 28, no. 5/6, (Oct.–Dec. 1998): 713–40.

[ii] Lawrence Schiller and James Willworth, American Tragedy (New York: Random House, 1996), 329–31.

“Allow repetition to take the place of responsibility to fact, history, truth.”

Boom. There it is.

Let me just say that some headlines made me smile yesterday, and this was at the top of the list. I feel the same about the story involving this guy. I was on a federal jury once (it's all it takes) and watched exactly what you are describing play out. I was the lone dissenter and made us all have to return to continue deliberations. That night I laid out all the facts on paper that we knew to be true to present to the others, and each and every one of the 11 jurors saw the light and thanked me. I do not hold juries in very high regard just from my one experience. Thank you for writing this.