The King’s Two Bodies

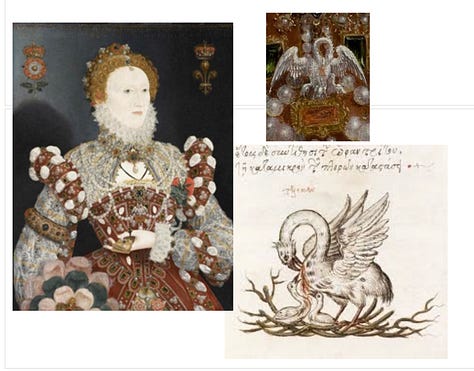

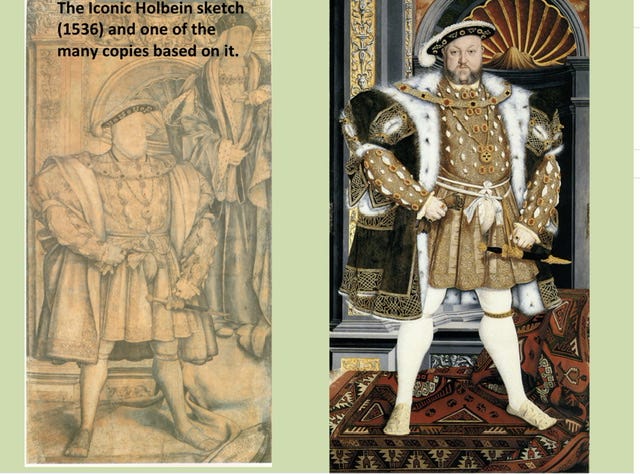

Lacey Baldwin Smith has written that “Tudor portraits bear about as much resemblance to their subjects as elephants to prunes.” A slight exaggeration, maybe. But it is true that the historical accuracy of the depictions in Tudor portraits, particularly of royalty, was often at war with “symbolic iconizing”—the use of imagery to represent the person’s character, position or role. The symbolism could include inscriptions, emblems, mottos, relationships with other people, animals, or objects, and it could also be written into the body itself. A famous example is Hans Holbein’s sketch of Henry VIII—the painting itself was destroyed in a fire—with the king posed to emphasize his power, authority, and resoluteness: legs spread and firmly planted, broad shoulders, one hand on his dagger, and a very visible codpiece (larger, art historians have noted, than portraits of other men at the time.)

Did Henry look like this? Portraits from the early years of his reign show a young man that bears little resemblance to the powerful giant, and some visitors to the court remarked that his good looks—which of course were constantly commented on—were somewhat feminine.

There are later portraits that look quite a bit like the Whitehall Henry, but beyond his height and measurements, which we can determine from his suits of armour, and his ginger hair, which ran in the family, we have little reliable knowledge of what Henry looked like, or how much later artists took from the Holbein rather than Henry himself. The Holbein is the king that we recognize as Henry VIII precisely because it has been reproduced so many times, and it has been reproduced so many times because of its perfect fusing of the body of the king and the idea of his Kingliness.

As medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz would describe it, there are actually two Henry VIII bodies depicted in the Holbein: The first is the representation of a mortal, flesh-and-blood man, who at the time of the sitting had a specific height, weight, age, and as we now know, serious problems with his leg, a gradually increasingly waistline, and possibly intermittent erectile dysfunction. The other body, which Henry himself as well as legions of viewers since him immediately recognize, is an enduring, ageless icon of masculine power and authority. His leg is as sturdy and pain-free as in his youth, his mind is uncluttered by remorse or uncertainty, he is ever potent, ever the warrior.

The notion of the King’s “two bodies,” first made prominent by Kantorowicz, is a slippery concept. Medieval legal theory distinguished between what was called the king’s “body natural”— the mortal body, which just like every other moral body is subject to physical defects, disability, aging, disease, accidents, and death--and the “body politic”, which includes his policies and forms of government and all of his subjects, an idea nicely captured in the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, depicting the monarch as the head of the state's corporate body. There are other traditions which endow the King’s second body with a more mystical cast, as something like the “soul” or “spirit” of his sovereignty, which God has bestowed on him. And there are some, like Thackeray in his 1840 caricature of Rigaud’s portrait of Louis XIV, have laughingly and literally deconstructed that idea, exposing the naked, puny “natural body” beneath the trappings of monarchy, which appear as mere fashion accessories.

In this pair of pieces on “The Royal Body,” I’m going to use the concept very loosely and unorthodoxly, as a means of conveying some of my thinking, not about England’s kings, but their queens and queens-to-be. For despite Kantorowicz’s characterization of the mystical second body as without flesh, blood, shape or, presumably, sex, one of the things that the two bodies concept exposes very neatly is just how tethered to the male body the idea of English royal authority has been historically. But no reign is permanent, and I’ll also be discussing some challenges to that partnership.

The first challenge that I’ll be looking at, in a section called “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Elizabeth,” is about Henry’s daughter, who both in her own lifetime and beyond has stirred up discomfort with the idea of royal authority being invested in a female body, but who also came up with some ingenious strategies for making that idea palatable. The second challenge I’ll be looking at, which I call “The Revenge of the Consorts”, is about Anne Boleyn, Princess Diana, and the power of popular culture to create a “third” royal body that speaks for the silenced wives. (This part will be posted tomorrow.)

2.“How Do You Solve a Problem Like Elizabeth?”

There have been many writers who have described the idea of a woman controlling a kingdom as an abomination—from Elizabeth’s own time, most famously John Knox, whose 1553 diatribe The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, argued that the woman who presumed to reign was a “monster in nature.” The argument is familiar: By nature, we are “weak, frail, impatient, feeble, and foolish” and experience has shown us to be “unconstant, variable, cruel, and lacking the spirit of counsel and regiment.” The notion that women are unfit to rule is kind of a yawn. But what the two bodies concept shows is that our liabilities have been representational as well. For, as we have seen with the Holbein, when the monarch is a man, the flesh-and-blood body and the body of monarchical power work in tandem. When the monarch is female, however, the situation is very different. The female body, being associated with inferior intelligence, emotional instability, and indeed, as Beauvoir famously wrote, with the body itself, “weighed down by everything peculiar to it” is virtually defined by it’s flesh-and-bloodiness and all its imperfections.

As a particularly clear example of the partnership between the two bodies of the male manarch, we have the codpiece. It houses a flesh-and-blood penis, which engages in (and can fail at) the biological functions of sex and reproduction. But as ostentatious armor for that flesh-and-blood organ, it transcends the biological to symbolize the phallus, invulnerable, unchangeable, always upright and at the ready—and in early modern portraits, intentionally so. As Patricia Simons puts it, in early modern portraits, the codpiece is “a surrogate political weapon.”

The phallus, as I argue in The Male Body, is not a body-part; it’s a cultural symbol, an idea—the idea of masculine authority and power. That idea, of course, can be projected onto the flesh-and-blood penis—as in Lady Chatterley’s Lover and numerous romance novels celebrating dazzlingly potent male sexuality—and it can also be symbolized in buildings, rockets, automobiles, and so forth. For Henry VIII, phallic power was tied to generative ability via the capacity to bring forth male heirs. “Am I not a man like any other?” he is said to have thundered when Chapuys dared to suggest that perhaps Henry’s union with Anne Boleyn wouldn’t produce an heir. “A man like any other” here is no lowly thing, for the ability to generate heirs to insure the continuance of the Tudor line is not just (or even primarily) biological—it’s cosmological, it secures Henry’s immortality, and preserves his kingdom. A king is never merely a reproducer. Or to put it in terms of the two bodies concept, when the king reproduces, both bodies are doing their work.

The flesh-and-blood penis, however, never quite vanishes from the mind’s eye—at one time, for example, the Victorians took Henry’s suits of armour off display because women trying to conceive would stick flowers in the codpiece—but the fact that Henry could impregnate a woman did not mitigate his kingly authority. Quite the opposite. “Am I not a man like any other?” he is know to have thundered when Chapuys dared to suggest that perhaps Henry’s union with Anne Boleyn wouldn’t produce an heir. “A man like any other” here is no lowly thing, for the ability to generate heirs to insure the continuance of the Tudor line is not just (or even primarily) biological—it’s cosmological, it secures Henry’s immortality, and preserves his kingdom. A king is never merely a reproducer. Or to put it in terms of the two bodies concept, when the king reproduces, both bodies are doing their work.

Queens, of course, are required for the king to succeed at that, and Henry is notorious for his difficulties in making that happen, difficulties that have led medical anthropologist Kyra Kramer to postulate that Henry’s blood carried an antigen—called Kell—that seriously affected his wives’ ability to carry any children after their first to term. It’s interesting, but impossible to prove, of course, without extracting Henry’s DNA. What we do know, though, is that Katherine of Aragon’s, and then Anne Boleyn’s failure to produce a male heir was taken by Henry as a sign from God that he was married to the wrong woman. It was unthinkable that it should be Henry’s fault, for as we have seen, when the monarch’s body is male, the biological body and the second, more mystical body of kingly authority operate in tandem, a supportive pair.

The biological body of the queen, in contrast, like all female bodies an undependable quagmire of female stuff, only becomes mystically aligned with God when chosen by the King, and that mystique only lasts so long as she produces heirs. So it’s no wonder that Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I, felt the need to dissociate herself from that female body, as in her famous speech at Tilbury, to the troups about to fight the Spanish Armada. Here is Glenda Jackson performing that speech from the 1971 mini-series “Elizabeth R”:

When Elizabeth uses the term “heart” here, she is speaking of “courage” (the Latin root for “heart” being “cor”) not the site of emotions or sentiment; “stomach” refers to pride (similarly, “stout” in those days meant “proud.”) But the series Elizabeth R is virtually alone in portraying a proud, courageous, commanding ElizabethBut the series Elizabeth R is virtually alone in its comfort portraying a confident, commanding, grown-up Elizabeth. Bette Davis, in the 1939 film “Elizabeth and Essex” and even more so in the 1955 “The Virgin Queen” is a lovelorn mess and a “capricious bully,” who despises ordinary women for their ordinary pleasures, and refers to herself as “an empty glittering husk.”

Jean Simmons, in 1953’s “Young Bess” is definitely her father’s daughter—the film even has her striking the same pose as Henry VIII, played by Charles Laughton, but she’s just a teenager in that film. Judi Dench is both human and regal in Shakespeare in Love—she’s probably my favorite Elizabeth--but she has a bit part in that film. The recent films that have foregrounded Elizabeth—HBO’s mini-series with Helen Mirren and Shekhar Kapur’s two movies with Cate Blanchett, seem to equate “humanizing” with humiliating.

The 1998 film in particular, written by Michael Hirst and starring Cate Blanchett, goes out of its way to present many moments of bumbling insecurity. One of the most gratuitous and annoying shows her preparing for her first confrontation with Parliament, stumbling over her lines, stopping and starting over and over, like an actor who has forgotten his cues. Now, Elizabeth may well have had her moments of wavering and insecurity—she was notoriously slow at making decisions—but, as a scholar and a wordsmith, nerves before public speaking does not seem to have been a problem for her.

As for having the “heart and stomach of a king”, Elizabeth’s chief torment throughout Kapur’s film, unlike Elizabeth R, whose first episode is called “The Lion’s Cub,” is that she is not “her father’s daughter.” The directions for the shooting script, in a scene in which Elizabeth is distraught over the dead young men that she sent to war in Scotland, are telling:

“Elizabeth strides through the corridors…emerging into a huge, long-disused room. Tear of anger and humiliation well in her eyes. She sobs aloud. She is like a wounded animal…stumbling, crying, overwhelmed…and then, abruptly, she stops. Through her tears she finds herself looking at the vast, masterful portrait of her father, Henry VIII, by Holbein. She stares at it, choking back her sobs. The portrait shows Henry in the full flush and pomp of his power: a big, powerfully built man, his eyes flashing with arrogance, his legs planted apart. The embodiment of kingly virtues, of supreme confidence and power….”

“My father would not have made such a mistake.” She tells Walsingham. “I have been proved unfit to rule.” Score one for John Knox.

Ultimately, of course, Elizabeth comes into her own, and in the sequel, “The Golden Age,” delivers her own Tylbury speech, attired in dazzlingly fashionable armour—which she may or may not have actually worn, it’s a motif in some paintings but never mentioned in accounts from the period—her long red hair unbound and whipping about her face in the wind as her apparently untrained horse shows her glamorous androgyny off to full advantage. Actually, androgyny is not quite right. She’s more like a young girl—and Elizabeth was actually 55 at the time of the defeat of the Spanish Armada--playing dress-up as a knight in armour.

But what happened to “heart and stomach of a king?” The answer is made clear in the 2006 HBO production, starring Helen Mirren and Jeremy Irons:

Blanchett’s Elizabeth apparently didn’t have the earl of Leicester to help her come up with the immortal phrase.

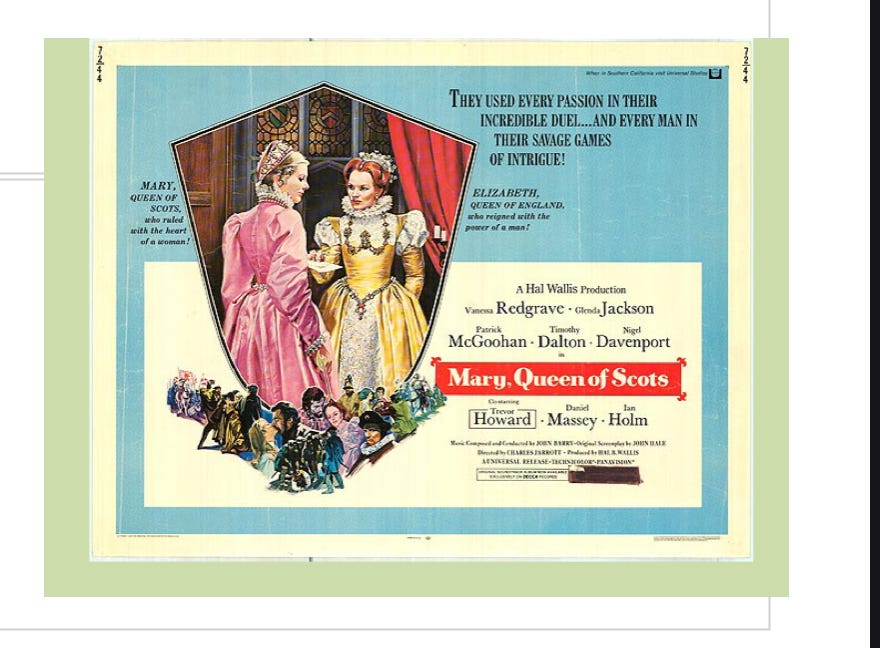

These fairly recent representations are just new tweaks on old solutions to a very old problem, which the actual Elizabeth struggled with throughout her reign. To be kingly, it was necessary to disown the “weak and feeble” female body. But at the same time, to be not female enough is to invite suspicions and accusations of being “unnatural.” In the movies, the strategy for making bossy Elizabeth at all sympathetic, from Bette Davis through Helen Mirren, has been to throw enough romantic heartbreak (via Leicester and then Essex) in the way of her happiness to make it clear that the renunciation of her female body was a hard, painful choice necessitated by her position. “The necessities of a queen transcend that of a woman.” “To be a queen one must give up all a woman finds dear.” “To be a queen is to be less than human.” These are quotes from Elizabeth and Essex which are essentially reproduced in various forms in virtually every Elizabeth film. Often, the idea forms the very basis of the plot, as in 1972 Mary Queen of Scotts, starring Glenda Jackson and Vanessa Redgrave.

In her own time and after, Mary was seen as the “true,” natural woman. But the price she paid for her love affairs, which rarely worked out very well, was to be seen as having “more heart than mind.” (“Heart” here meaning emotionality rather than courage.)Elizabeth, who from an early age had seen the kind of disasters that dependence on the heart can lead to, wasn’t going to make that mistake. But at the other end of the spectrum was the danger of being seen as a man in drag, or, as Hillary Mantel described Margaret Thatcher recently, a “psychological transvestite.” This charge was popular among Elizabeth’s detractors, both in her own lifetime and during those periods when Elizabeth’s failure to behave in a gender-normative way jangled cultural nerves especially harshly.

Victorians, for example, as Michael Dobson and Nicola Watson argue, had a big problem with Elizabeth’s seemingly willful rejection of domesticity, which stood in stark contrast to the ostentatiously wifely—and very fertile—Victoria. They made her pay for it by replacing sentimental imagery of an older but still beautiful Elizabeth, capable of sexually appealing to the much younger Essex with an aging, barren hag, whose femininity was composed of wigs and make-up. Contrast, for example, Robert Smirke’s 1806 depiction of Essex bursting unannounced into Elizabeth’s bedroom with David Wilkie Winfield’s 1875 version of the same incident.

Historian David Starkey argues that Elizabeth’s solution to the dilemma of the male/female either/or and you-can’t-win-matter-what you do was to construct herself as “royal hermaphrodite,” who seemingly ruled like her father’s son (as in the Mary Queen of Scots poster above) but who got her way by flirting and manipulating the men of her court. This is another familiar depiction of Elizabeth. “She was a masculine woman simulating, when it suited her purposes, a feminine character,” wrote Edward Spencer Beesly in 1892, “The men against whom she was matched never knew whether they were dealing with a crafty and determined politician, or a vain, flighty, amorous woman.” Beesly’s own misogyny has muddled things up here; if Elizabeth’s femininity was a simulation, why would she “simulate” the worst traits associated with women? The more plausible idea, and as suggested by the historical evidence, is that Elizabeth was both a smart politician and a woman who genuinely enjoyed and did not merely simulate courtly banter, flirtatious teasing, and the admiration of the men around her. She didn’t have to fake either side of her personality; if her father and mother are any evidence, she came by both quite “naturally.”

But whatever Elizabeth was like among the men of her court, representation for the public was a whole other arena. And so, as Roy Strong has argued, to win the admiration and love of her subjects, Elizabeth, with the help of her courtiers and officials, would develop a whole new vocabulary of public symbols, establishing a “cult of Elizabeth” (as Strong calls it) to replace the idolatory of the Virgin Mary that was banned from her officially protestant england. Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth condenses this notion in an over-the-top episode which begins with Elizabeth gazing enviously at a statue of The virgin Mary, wondering how she had “such power over men’s minds.” Walsingham, who has been watching, tells Elizabeth “They have found nothing to replace her.” Click, click goes off in Elizabeth’s brain, and next thing you know she is shaving her head, painting her face white, and declaring, “Look. I am become a virgin.”

Elizabeth’s symbolic personae, however, was only part Virgin Mary, and scholars like Susan Doran have argued that it’s wrong to over-emphasize the “virgin” part, except in terms of more pagan rather than Christian associations, not indicating an intact hymen but a woman “sufficient unto herself” rather than in need of a Leicester to write her speeches for her, to complete her. And the Virgin Mary, besides being a virgin, was also a mother, and many of the symbols in the most famous paintings of Elizabeth, employ other symbols of generativity—the phoenix—and material self-sacrifice—the pelican, often depicted in renaissance bestiaries as sucking blood from its own body to feed its young. And then, too competing alongside the Virgin and the Mother was the fairy queen, ageless and beautiful object of heterosexual adoration, radiant as the sun …the perfect and pure mistress to whom the knight owes his homage.” And after the defeat of the Armada, “Gloriana,” symbol of English conquest, military success, and ownership of the globe.

Kevin Sharp describes all this symbolism and imagery as an “effacement of the Queen’s body.” “The portraits,” he writes, “divert attention from the queen’s sexual and regenerative body…and render her the timeless, eternal mother and virgin.” I think, however, keeping the concept of the two bodies in mind—a concept of which Elizabeth was well aware—that what is happening here is a redefinition rather than effacement of Elizabeth’s biological femaleness so that it was consonant with her body as monarch, just as her father’s biological maleness was consonant, indeed virtually inseparable from, his kingliness.

The strategy was to transform the literal into the metaphorical. So, the reproductive body, which Henry had associated with the ability to bring forth male heirs—a conception that cast both her mother Anne Boleyn and her own self as lacking—was recast by Elizabeth as embracing maternal nurture of her subjects. This wasn’t a new idea—Mary Tudor had also represented herself as mother of England—but while Mary struggled, unsuccessfully, to also fulfill her more literal role as the producer of heirs, Elizabeth bumped that off the table--very early in her reign, according to her earliest biographer William Campbell.

It was 1559, and the House of Commons was pressuring her to choose a husband, arguing that “nothing could be more repugnant to the common good than to see a Princesse…lead a single life, like a vestal nun.” According to Camden, Elizabeth had replied that she was “already bound unto a Husband, which is the Kingdome of England” and went on to tell them to “reproach me no more, that I have no children: for every one of you, and as many are English, are my children.” Thus “I cannot without injury be accounted Barren.”

Scholars have questioned whether of not Elizabeth spoke these words exactly as Camden reported in 1625, but historical accuracy is not required for myth-making. Whatever exact words were used, there is an “argument” here—and it is one that recasts motherhood from a biological capacity to motherhood as symbolic of the “second” body of monarchy that female rulers had lacked. In doing so, Elizabeth not only created a female body-imagery of immortality for herself but turned her own mother’s failure to produce a male heir into a brilliant (albeit self-sacrificial) success.

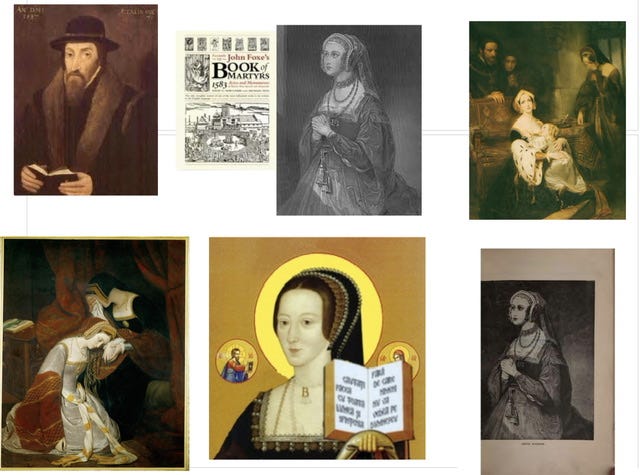

In Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, George Wyatt’s Life of Queen Anne Boleigne, and John Banks’ Vertue Betray’d, the new imagery of Anne as mother of a new age then becomes the first, emerging iconography of Anne Boleyn to compete against the Catholic representation of her as a shrewish, vindictive destroyer of Henry VIII’s virtue and the “true religion” of the realm. As the Queen who gave birth to Elizabeth and—as protestant defenders now saw her—the mother of the glorious reformation, Anne was endowed with a “second” body as well, no less divinely “elect” than Henry’s, with Anne chosen by God to be “a most eminent agent and actor “ in the “greate and remarkable convertion” of the reformation (Wyatt.) Banks, in even more hyperbolic prose, predicts Anne’s vindication once the “holy Tyrant” who “holds his feet upon the neck of Kings” is destroyed by Elizabeth; then, Anne Boleyn’s daughter will “rise like a star…and awe the Southern World.”

The imagery of Anne as the mother of the reformation has not had as long or tight a grip on the cultural imagination as has our “default Anne” (as I call it): Chapuys’ vile plotter, Sanders’ promiscuous witch, the “bad woman” of 19th century male historians, Gregory’s “mean girl,” Mantel’s cold, feral schemer. But in the end, they are all cultural creations, no less products of “symbolic iconography” than Holbein’s Henry or Elizabeth’s Gloriana. They don’t convey factual knowledge about their subjects, but they tell us a great deal about the history of myth-making.

PART TWO: THE REVENGE OF THE CONSORTS (ANNE AND DIANA) COMING TOMORROW!!

.

I am a great fan of Alison Weir’s biography of Queen Elizabeth. In it she theorizes that Elizabeth was wary of childbearing as she had seen many poor outcomes as she was growing up. Weir presents a picture of Elizabeth as strong, but womanly. She was very intelligent and translated the Bible and other books from Latin to English. She was fluent in Latin, actually. But she also liked to flirt and to dance. She loved beautiful clothes. Weir presents her as a man’s woman. She preferred the company of men. The only women in her court were her ladies in waiting. Yet when her favorite one died, she died soon after. As she got older it became more difficult for her to retain the respect of her male courtiers.

But for me she was a role model from the time I was about 12. That’s when I started reading biographies about her, starting with “Young Bess.” At a time when women had no power, I chose a queen as my role model. She was unique in her time and would be unique in ours as well.

The white makeup was worn to conceal scars from her bout with smallpox, so far as I recall. She also did see England, the realm, as her husband. And given that she knew she was a catch for any male she married, she preferred to retain control of her body and her kingdom by not marrying. Who can blame her?