May 19, 1536: Anne Boleyn, convicted of treason, adultery, and incest, became the first Queen in English history to be executed. She died with many enemies, mostly Catholic, who described her as a scheming harpy, “goggle-eyed whore” and Lutheran heretic, who ensnared Henry with her French ways. Chief among them was Eustache Chapuys, imperial ambassador to Spain, who viewed Anne as a scheming non-royal interloper who destroyed all that was good about Henry VIII, plotted to poison Katherine and Mary, and simply refused to stay “in her place.”

According to this old but amazingly enduring view, which has become what I call “our default Anne,” Anne used her sexuality to lure Henry from his devout first wife, interfered in matters of religion and politics, was demanding, bossy, and unwilling to tolerate what good wives were supposed to endure in silence—most famously, Henry’s straying. Too ambitious, too vocal, and therefore not a proper queen. Not like Katherine, who had been raised to be chaste, obedient, to speak up “only when it would be harmful to keep silent” and to “administer everything according to the will and command of her husband.” (Those are quotes from Vives, Education of a Christian Woman, written in 1523 for Katherine’s daughter Mary.)

This isn’t the place to sort out myth from reality here, or to detail the complexities of Anne’s fall. (See my book, The Creation of Anne Boleyn, for that.) Suffice to say that when her enemies finally got their way and had her mortal body silenced, it backfired on them and Henry in a big way in terms of her enduring cultural prominence. Even before her execution, Henry, determined to start life afresh with a new, more obedient consort, had been busy at work attempting to erase Anne’s life from the recorded legacy of his reign. He got rid of her portraits. He apparently destroyed her letters. He even had workmen remove the entwined H’s and A’s strewn throughout the walls and ceilings of the Great Hall at Hampton Court.

He missed several. More significantly, he failed utterly in the attempt to make Anne disappear. She is undoubtedly his most famous wife.

Here are a few highlights from her vibrant and varied cultural afterlife:

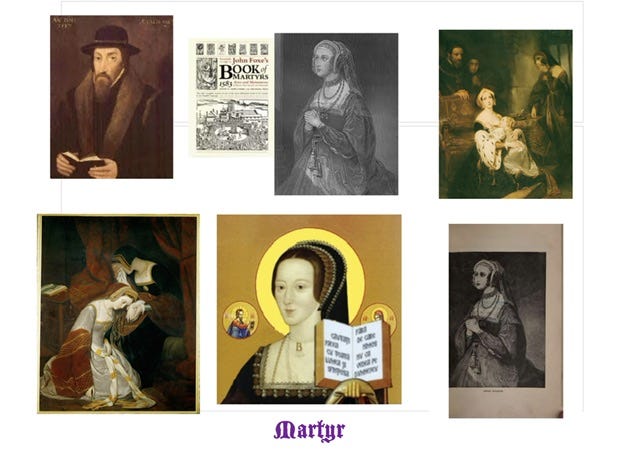

After Anne’s daughter Elizabeth ascends to the throne in 1558, Protestant defenders begin to emerge from the closet. In their eyes, Anne Boleyn is the mother of the Reformation, a “most virtuous and noble lady” who helped bring true religion to England.

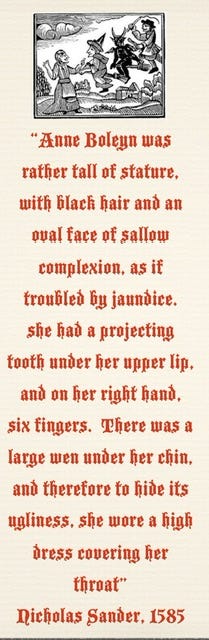

Then, in 1585, pro-Catholic Nicholas Sander, exiled by Elizabeth, writes that not only did Anne sleep with half the French court and her father’s chaplain, but she is actually Henry’s daughter, by her own mother. She is also grossly deformed, with a projecting tooth, large growth on her neck, and six fingers on one hand. It’s a myth—Anne had an extra nail, not an extra finger—but most people still believe it’s true.

In 1682, John Banks (following the “Secret History” of Madame D’Aulnoy, famous French writer of fairy-tales) and others cast a new narrative of love and betrayal and create a new dramatic persona: the “she-heroine.” Ingredients: clever, virtuous girl, wicked king, scheming “other woman,” and tragic ending. The soap opera begins.

Between 1700-1900, opinion about Anne begins to get divided along gender lines. Is she a Fallen Woman or Scheming Adventuress? The Strickland sisters see Anne as a cautionary tale, while Anthony Froude and other male historians view her as a “foolish and bad woman” who corrupted Henry. The male historians have nothing but scorn for the “sentimental” “tiddle-tattle” of the women writers—conveniently overlooking the fact that their own research relies largely on the gossipy letters of Eustace Chapuys, imperial ambassador to Spain! (And Katherine’s dear friend). While the writers battle it out, romantic painters have the last word in the popular imagination. Anne—often now depicted as blonde and rather plump—is shown swooning, weeping, and stoicly meeting an unjust end.

1912-1939: The Victorians had mangled the date of Elizabeth’s birth to avoid confronting the fact that Anne and Henry had slept together before they were married. The birth of the historical romance makes their premarital sex mandatory. And the fictional juice begins to flow…and flow…and flow. Love. Longing. Loathing. Lust. By the time she is published in paperback (Francis Hacket’s Queen Anne Boleyn) the story has become the stuff of the back-cover salespitch: “She conquered the heart of a king—and lost her life for her love.”

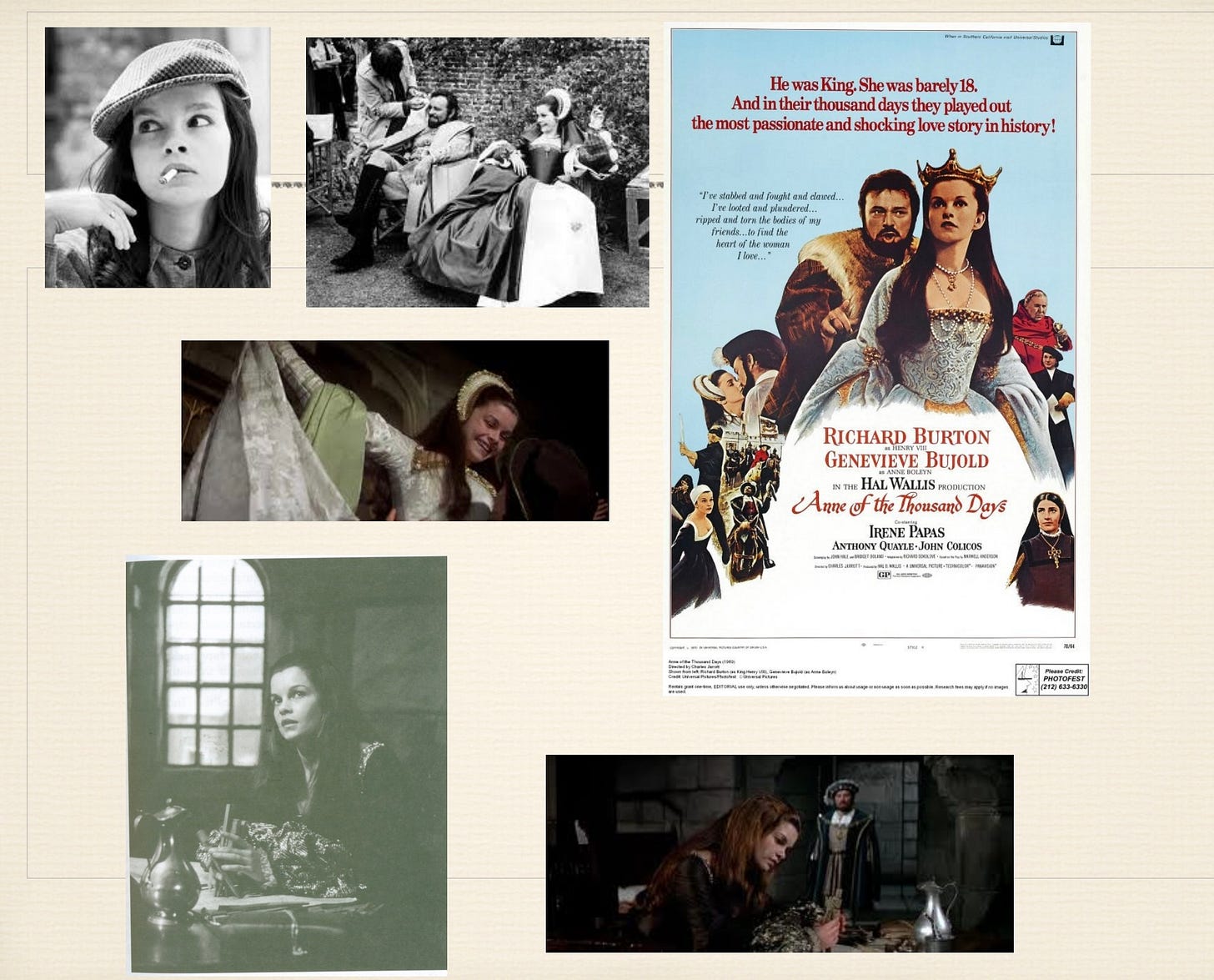

1969: Anne of the Thousand Days (film): In an interview with me, Genevieve Bujold told me “Anne is mine.” Indeed. As the first truly iconic Anne, Bujold proudly plunges off the cliff decades before “Thelma and Louise.” We were charmed by her elfin beauty, we cheered when she told Henry off in the tower (never happened, but who cares?), and yes, “Elizabeth Shall Be Queen!”

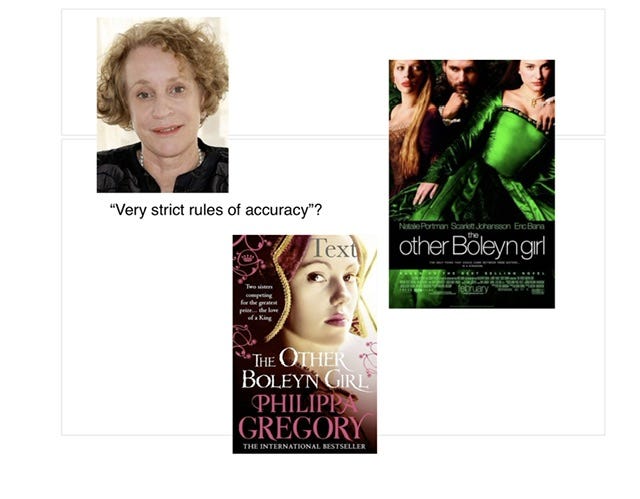

2002: Philippa Gregory’s “The Other Boleyn Girl”: Clearly in touch with the times, Gregory mangles history to produce the nastiest Anne ever, and convinces a new generation, befuddled by the postmodern blurring of fiction and fact, that she really did sleep with her brother. Sander is chortling, historians are grimacing, and Gregory is smiling all the way to the best-seller list.

2007: Showtime’s “The Tudors”: Jonathan Rhys-Meyers refused to wear a fat suit, the Showtime execs demanded hot sex in every episode, and Michael Hirst (creator and writer of the series) tried to inject a bit of the Reformation Crisis in between the scenes of Henry romping in bed. Only Natalie Dormer, barely known at the time, stood up for Anne, refusing to play her as a blonde and insisting that Hirst make her less slutty, smarter, and stronger in the second season. For historians, the changes may have seemed slight. But teenage and twenty-something viewers were enraptured. “She was a modern day girl in the wrong time period,” they declared, constructing a new, “third-wave” feminist icon out of Dormer’s portrayal: ambitious, intelligent, flirtatious and perhaps most important to her fans, “hugely complicated and not easy to dismiss.”

15 years ago, when I was talking to prospective editors about my book, one—from a major press—said skeptically “Do you really think there’s still interest in Anne Boleyn?” Luckily for me, she was a bit out of touch. With “The Tudors” came the websites…and the tee-shirts, mugs, and jewelry…and the facebook pages…and a whole new stream of bios, novels, films, and plays.1

My point: Anne, a wife whom Henry desperately wanted to erase, is in fact his most represented consort. Post-structuralist theorists would say that this makes sense: what we try to bury or make marginal, by its very suppression, keeps making itself known—and with the aid of modern media, deployed in a multiplicity of ways. Henry could destroy the symbols that HE had created, but he couldn’t prevent the unfolding of a cultural afterlife that so far shows no signs of ending. Ironically, Anne—who wasn’t born to be royal—wound up having the immortal body of royalty, as a cultural creation.

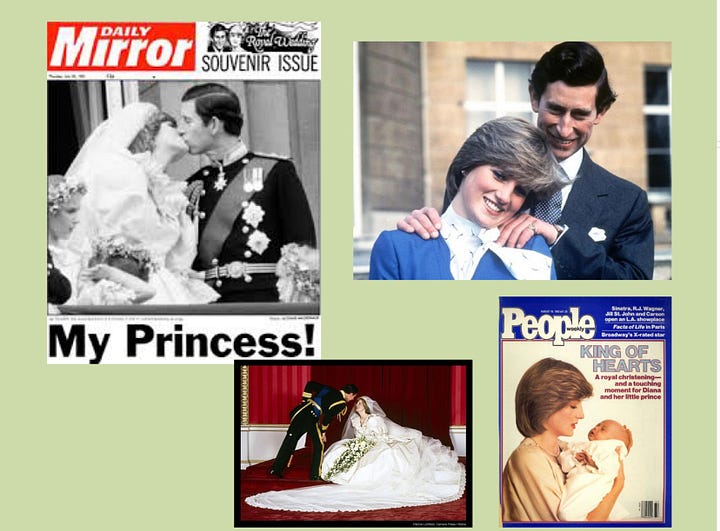

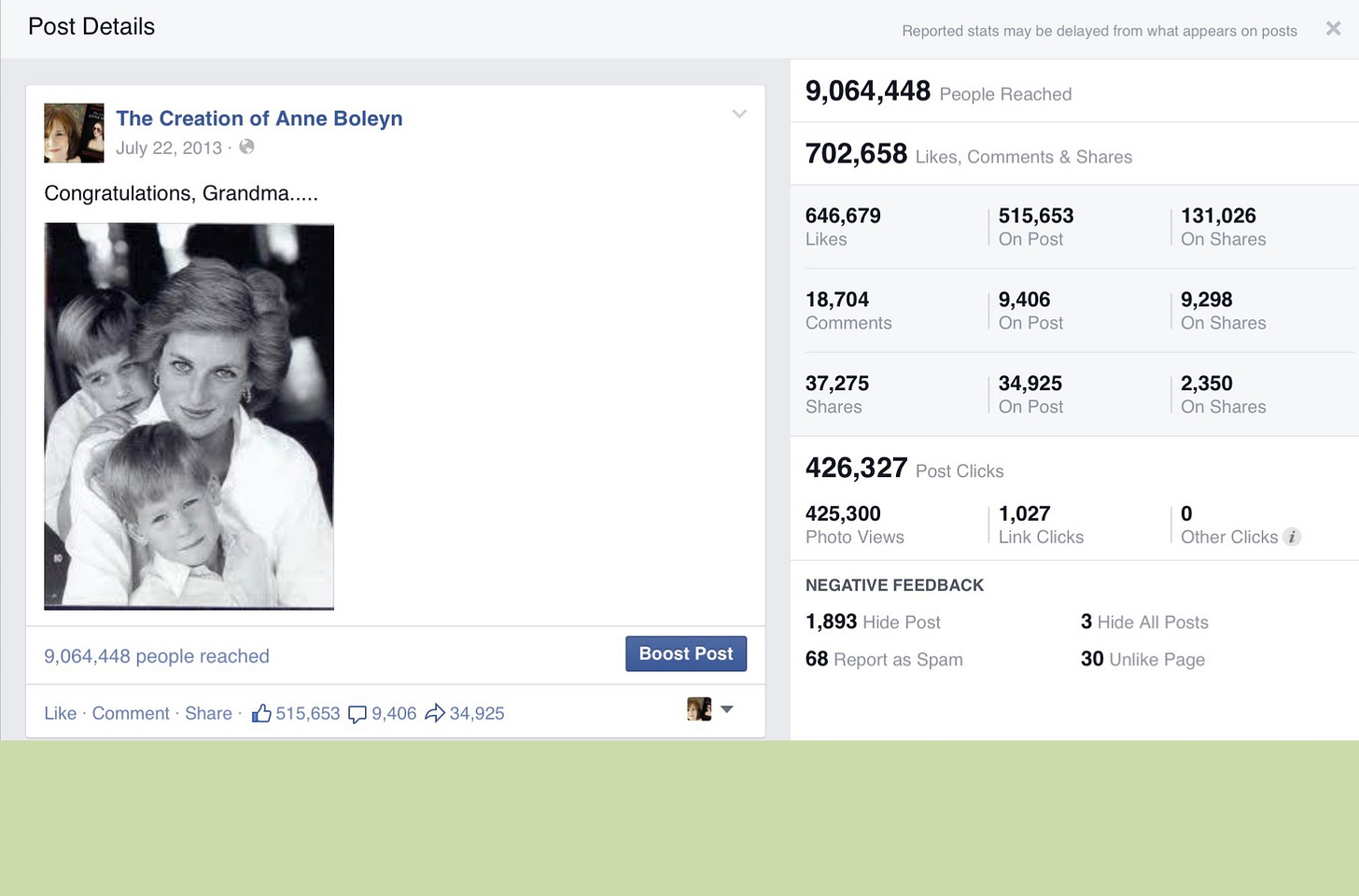

July 22, 2013. Three months earlier, The Creation of Anne Boleyn had been published, and my book’s Facebook page had been filled for weeks with postings about the upcoming birth of the royal baby. The world was entranced with the latest unfolding of the fairy tale. I was swept up, too, but also growing annoyed at what seemed to be the eclipse of that other princess—the one who wasn’t quite so skilled at behaving as Queen consorts-to-be are supposed to—and getting tired of the endless coverage of Princess Kate’s “royal bump.”

Princess Kate seemed so different from Diana “whose human awkwardness and emotional incontinence showed in her every gesture.” (Hillary Mantel) Her biographer Rosalind Coward, who does know her better than most, wrote that she presents “no immediate danger of going off like a loose canon…Unlike Diana, this is a woman well-briefed and carefully supervised.” When the queen embarked on a series of Diamond Jubilee tours of Britain’s provinces, she even “took with her the newly minted duchess as if to finally lay to rest Diana’s ghost.”

It was irritating. Didn’t anyone remember that there was another Princess for whom the fairytale didn’t end so happily? Why isn’t there any mention of the royal bump’s deceased grandmother? Have we so easily replaced one glamorous mama-goddess with another? Annoyed, on the day George was born I posted this photograph of Diana and her sons, with the caption “Congratulations, Grandma.” It was purely for my own satisfaction; I didn’t expect more than a few dozen “likes.”

Instead, the post went viral, and the comments extolling Diana poured in by the thousands.

And it struck me that this picture was every bit as much an icon as Holbein’s Henry VIII or Elizabeth I’s Gloriana. And I was put in mind, too, of the queen about whom I’d just written a book.

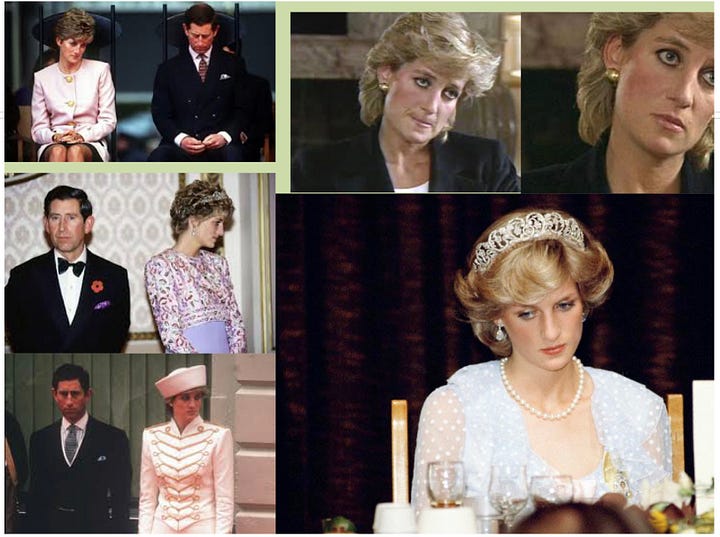

Diana and Anne seem on the surface to have little in common, with Diana now venerated and Anne constantly caricatured as a nasty, narcissistic schemer. But scratch the surface of the stereotypes and their sisterhood appears. Like Anne, Diana had challenged the power and authority of the monarchy to decide what her rightful role as the future King’s wife should be. Diana, too, had been viewed by her enemies as a bossy, overly ambitious, non-royal interloper who refused to behave as she should and was unwilling to tolerate the infidelity that good wives were supposed to endure in silence. Instead of waving and smiling while her fairy tale fell apart, Diana spoke up, drolly remarking, in her famous Panorama interview with Martin Bashir, that her marriage was “a bit crowded” as there were “three of us in it.”

The initial price she paid for her failure to be silent was to offend a powerful network of country club and court who, for a time, seemed in control of the situation: “The mantra,” wrote one of Diana’s biographers, “was that Diana was a scheming girl who had set her cap at Charles and got him…[But] she [turned out to be] impossible to live with,” ferociously possessive, and “cruel and domineering” both to her staff and Prince Charles. Sound familiar to Anne Boleyn aficionados?

But Diana, unlike Anne, had weapons to fight back with, chief among them a modern media machine capable of promoting her personal glamour and warmth, as well as her caring, maternal activities. People particularly cheered her refusal to accept that being emotional did not go along with being royal. “I lead from the heart, not the head,” she told Bashir. But that was just fine as far as Diana was concerned, for she wanted to reign not officially but as a Queen of Hearts, giving affection and helping others. Quite an interesting reversal of the age-old notion, which has often been used to contrast Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I, that rulers must choose in favor of intellect over love, male mind over female body. It all depended on what sort of throne you wished to sit upon, Diana suggested.

With her death, however, the worship of her as “Queen of Hearts” exposed that even the official throne was in need of more “heart” when the Queen, at first, stayed away from the mourning crowds and refused to fly the royal flag for Diana. “Show us there’s a heart at the house of Windsor” the headlines blasted, a painful moment for Elizabeth and one of the themes of Stephen Frears The Queen, which shows Elizabeth II as utterly baffled by the seeming change in the rules of the game. She’s done what she thought was expected of her, only to find that she was hated for her coldness and formality. She confides in Tony Blair:

“Ever since Diana people want glamour and tears…the grand performance…and I’m not very good at that. I prefer to keep my feelings to myself…foolishly I believed that’s what people wanted from their Queen. Not to make a fuss nor wear one’s heart on one’s sleeve, duty first…self second. It’s how I was brought up, it’s all I’ve ever known.”

Diana, of course—and again like Anne Boleyn—was not brought up to be a royal. She didn’t even know much royal history, and fantasized about marrying prince Charles, “the only man,” she said, “who couldn’t divorce me.” “It could be quite fun,” she said to a friend. It would be like Anne Boleyn or Guinevere.” Her apparently more educated friend replied, “I bloody hope not!” For good and for bad, Diana’s marriage did turn out to be more like Anne’s marriage than she would have wished had she known her history. Although Charles was never passionately in love with Diana as Henry (apparently) was with Anne at the beginning, Charles was no less surprised than Henry to find that his wife actually expected fidelity from him—and no less outraged when she called him out on his behavior. Like Henry, he was rattled by Diana’s unwillingness to recede into the background. Like Henry, he expected that once she was out of the picture, not in death but in divorce, it would all go back to normal.

Has it? Or has Diana, like Anne, become “more royal than the family she joined”?

“It had nothing to do with family trees. Something in her personality, her receptivity, fitted her to be the carrier of myth.” (Hillary Mantel)……2

This talk, originally titled “The Revenge of the Consorts,” preceded several significant variations on Anne—including one (the film “Spencer”) that makes the Anne/Diana connection explicit, by having the ghost of Anne haunt Diana, warning of her own fate. More significant than the continuing fictional life of Anne has been the real-life royal drama created by Prince Harry’s marriage to Meghan Markle, now Duchess of Sussex. I had originally intended to update this talk before posting it today, but a nasty reaction to a shingrix vaccine interfered.

At some later point, I would like to carry this piece through to the present. Please do contribute your ideas!!

See footnote above.

Diana knew these creatures were evil, that’s why they took her out...🙏