“The Bear” is Not a Comedy

Selections from my stacks on all three seasons of “The Bear”

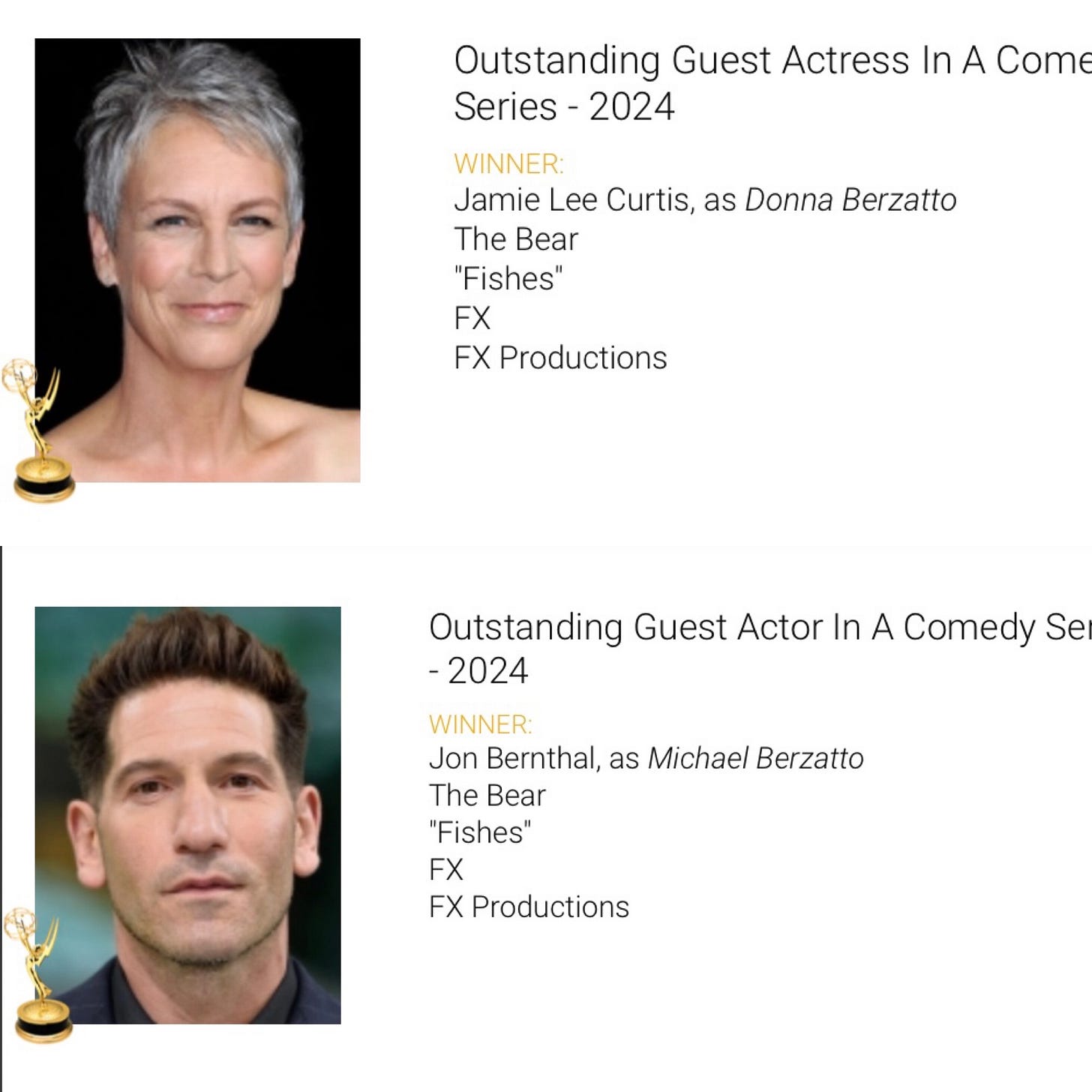

“One of the most persistent questions in television was seemingly answered last night, as the win for Outstanding Comedy Series went not to the reigning champ but to Hacks.”

And so, the Emmys 2024 voters finally decided “The Bear” Is Not a Comedy. As some of us have been arguing since the first season:

Season One (originally published June 26, 2023)

I’m not sure why more reviewers didn’t “get” how much “The Bear” is about what a long, ferocious tail grief has, particularly when that grief is over a beloved person who has hurt you and from whom you’ve become estranged. Maybe the hectic pace of the first season and the cleverness of the writing was as diverting to those reviewers who saw it as a “show about running a restaurant” as doing the running was to Carmy himself. But grief always catches up with you. Carmy left…time got away from him…and then his brother died. How to “process” that?

Season one leaves us wondering about the past, as it introduces us to the characters. We see explosive “cousin” Richie in a constant state of screaming agitation, always ready for a fight (and he almost does kill someone.) We watch irritable Line Cook Tina (Liza Colon-Zane) play nasty tricks on ambitious newcomer Sous Chef Sydney (Ayo Edibiri.) All that we know about Michael “Mikey” Berzatto, Carmen’s brother (John Bernthal) is that he was a magnetic personality who, possibly due to his addiction to painkillers, left his restaurant “The Original Beef of Chicagoland” in ruins, killed himself, and bequeathed the mess to Carmy (Jeremy Allen White.) The volatile, impossible-to-please alcoholic mother Donna Berzatto (Jamie Lee Curtis) doesn’t appear at all in the first season, but we know there’s something toxic there, because Carmy has come back from Copenhagen without getting in touch with her. When his sister Sugar, who is always trying to make it better, urges him to see her, he wordlessly communicates how impossible that feels. At this point, we don’t know what the problem is. .

Carmy himself isn’t overtly combustible like Richie, but we sense there’s a lot being tamped down, and perhaps about to boil over. In the original script by Chris Storer his sister Natalie (“Sugar”) (Abby Elliott) alludes to his punching someone at the restaurant he’d been working at, and later in the episode he throws a pot of gravy—sauce to non-Italians—against the wall. In the final version that we see, however, it’s just a can of Marzano tomatoes that he throws in the trash (without even looking at the contents, which turns out to be ironic.) Storer apparently made the (wise) decision to let Carmy’s inner struggle build up until he finally melts down in the penultimate episode of the first season. Until then, he lives on Tums and his turmoil is mostly externalized for the viewer in the drama of getting the restaurant and its diverse team cleaned up and in shape. No surprise that lots of reviewers praised The Bear as a realistic look into the stress and chaos of the restaurant business. “You may never get a more extraordinary glimpse inside a restaurant kitchen than this” is the headline of a fairly representative review.

The show always was much more than that. In flashbacks like the one below (“Mikey Tells A Story”) we saw how much Mikey’s exuberance and confidence, while overshadowing pretty much everyone else in the room, was adored by his more reserved brother and sister, who expertly put together the braciole while Mikey and Rich entertain. (Watching this scene again after learning more about the family in the second season, I imagine Mikey was also an antidote to their mother’s depression. What Carmy didn’t know at the time was that Mikey was wrestling with his own.)

At the point where season one begins, however, the pleasures of sibling get-togethers is a thing of the past. Carmy—who was hurt and angry when his brother didn’t want to include him in running The Beef or creating a new restaurant—had been without contact with Mikey for a long while, as he (Carmy) pursued a career as a chef. Inheriting the restaurant has brought him home—but no longer integrated in the family, and seemingly detached from Mikey’s death too. (He didn’t go to the funeral, and when Sydney, who applies to work at the restaurant, asks what accomplished Carmen “is doing here”—at The Beef—he tersely replies: “making sandwiches.”) That’s just on the surface, though—he’s not only grieving over his brother throughout the season, trying to keep him alive through his frenetic attempt to revamp the restaurant, but he’s still haunted by what he experienced as Mikey’s rejection; he joins Al-Anon in part in order to figure out who his brother was in those last years. (See second clip below: “Carmy’s 7-Minute Monologue”)

By the end of the season, he’s only just beginning. He has his own belated meltdown and explosion, finally reads that good-by note from Mikey—“I love you. Let it rip”—starts to make that family spaghetti recipe that he’d bumped from the menu at the beginning of the season, and…well, you know what happens then.

Season Two

I loved the first season of The Bear. But, as if in response to those critics who, while praising it lavishly, saw it only as a very smartly written show about the inner workings of a restaurant, the second season goes somewhere else. There are still the scenes of behind-the-scenes restaurant chaos, but the writers seem to have taken the advice of the book that Sydney’s father gives her and that she carries around for months: Leading With Your Heart. I had to ask my husband why Coach K (Krzyzewski), who wrote the book about his “Successful Strategies for Basketball, Business and Life,” would figure so prominently in the show. He tried not to make me feel like an idiot about sports greats. And because I’m a compulsive researcher, I actually read a few pages of the book, and about how he turned a losing team around by listening rather than bullying, getting to know every member of the team intimately, and keeping his composure when things seemed to be falling apart.

“Emotion doesn’t necessarily have to be shown with your fist pumping,” Coach K writes. There’s a “different kind of heart—a sturdy heart, an unwavering heart,” that’s for others to “grab ahold of” when a tornado is coming. But different people manifest that sturdiness in different ways, and “a true leader will give people the freedom to show the heart they possess” through the building of relationships: “Because if a team is a real family, its members will want to show you their hearts.” (pp. 31-32, Leading With Your Heart).

That’s the kind of team that gets created in season two. And, although when we leave Carmy in the last episode he hasn’t recognized it (he believes he’s failed because he lost focus, forgot to call the fridge guy, and got stuck in the walk-in during the most hectic time of “friends and family night”), he’s the one who has been most responsible for giving the others the freedom “to show the heart they possess.” It’s Carmy who sends Marcus (Lionel Boyce) to Copenhagen to study with Luca (Will Poulter) the same pastry chef who taught him, Carmy who sends Richie to “stage” for the elegant Ever restaurant, where he learns the pleasures of caring for others (and himself) through restraint and respect, and in a wonderful conversation with the owner (Chef Terry, a cameo played by Olivia Coleman ) realizes he can start over. It’s Carmy who sends Tina to culinary school (equipped with his own knife), where she shines. And ironically, it’s Carmy’s accidentally locking himself into the walk-in that forces Sydney—with Richie’s help—to take over, restoring the confidence that has been wavering all season and her own very sturdy heart. Carmy can’t see that—not yet. But—excuse the overworked cliche— he’s a work in progress.

If season one portrays the characters’ attempts to deny grief and loss (not just of people, but of confidence and hope) by shutting down, running away, keeping their bruises hidden to each other, season two is about each character’s opening up—to each other and to us. (And of course—not to strain the metaphor—they open up a new restaurant too.) There’s so much we don’t know during season one that we discover in season two, because we get to know all the main characters more intimately, and It’s all done with such tenderness! You can see it in the lovely, unhurried close-ups, which make every pore and scar seem beautiful (and these are mostly not symmetrical, conventionally beautiful faces.)

Most significantly—but also most problematically for the character—Carmy opens up too, to the possibility of personal happiness with a girlfriend. (Molly Gordon as Claire) And then, because he’s still Carmy, he torments himself over saying some bitter, self-hating words about how no amount of personal happiness is worth the misery he’s feeling, and is sure he may have ruined it all. It’s not clear whether or not he has (I tend to think he hasn’t, because Claire is such a perfect girlfriend.) But what is clear is that like his mother (Richie even calls him Donna as he berates him through the door of the walk-in) he’s addicted to self-flagellation, even as he’s created such glorious opportunities (and beautiful food) for those who love him, he can’t enjoy it. There’s still some unforgiving God waving a finger. And—oh, did I identify with this!—when he’s happy he’s always looking for that other shoe to drop. When it does, it just proves to him how fucked up he is.

Sydney realized that the best part of the day was when she made that luscious omelette ( boursin, chives, sour cream and onion potato chips, and lots of butter) for Sugar. Richie learned that the joy of making an exquisite dish comes from showing people you care enough to put the time and effort in in to peel a mushroom. Can Carmy exorcise the demons in him to allow himself to experience that joy? We don’t know; it’s a cliffhanger ending; even though we see that Carmy is getting out of the walk-in, we don’t know if he’ll remain emotionally stuck.

Best Episode: “Fishes” (originally published Jan 13, 2024)I

In flashbacks during season one, we had seen how much Mikey’s exuberance and confidence, while overshadowing pretty much everyone else in the room, was adored by his more reserved brother and sister, who expertly put together the braciole while Mikey and Rich entertain.1 At the point where season one begins, however, the pleasures of sibling get-togethers is a thing of the past. Carmy—who was hurt and angry when his brother didn’t want to include him in running The Beef or creating a new restaurant—had been without contact with Mikey for a long while, as he (Carmy) pursued a career as a chef. Inheriting the restaurant has brought him home—but no longer integrated in the family, and seemingly detached from Mikey’s death too. (He didn’t go to the funeral, and when Sydney, who applies to work at the restaurant, asks what accomplished Carmen “is doing here”—at The Beef—he tersely replies: “making sandwiches.”)

That’s just on the surface, though—he’s not only grieving over his brother throughout the season, trying to keep him alive through his frenetic attempt to revamp the restaurant, but he’s still haunted by what he experienced as Mikey’s rejection; he joins Al-Anon in part in order to figure out who his brother was in those last years. Then, in “Fishes”—the centerpiece of which is most horrendous family dinner you’ll ever see or are likely to see (even though I’m sure there will be twinges of non-fictional recognition, particularly if you’re Jewish or Italian)—we get the reality behind what Carm has brooded about.

It’s not in the famous dinner table explosion, where we see a big part of why Carmen, Natalie and Michael find it so difficult to be happy with themselves. Perhaps the worst burden a child can grow up with is being constantly reminded of your inability to save those you love and depend on the most. They all try, but their mother’s needs are a mass of contradictions and a bottomless tunnel that twists and turns out of reach nomatter what they do. Leave her alone and she feels unappreciated; ask if she’s okay and she goes into a fury (“What am I, a child?” “Are you asking anyone else if they’re ok?”)

It’s an episode that’s painful to watch. But in a moment of escape from the screaming and recriminations, Mikey and Carmy are alone together (in search of saltines for Rich’s wife, who’s pregnant and nauseous) and one wishes that somehow Carmy had been able to take into himself what is clearly his brother’s love—to take that love into his heart and keep it there.

MIKEY: Saltines? You're kinda acting like

a saltine, you know that?

Why? Why?

What's going on with you?

I know there's something.

Just tell me. Come on, Carm,

I'm right here.

What's going on?

I gotta drag it outta you?CARM:-I just...

I just, I thought,I thought when I was back,

I could work with you, alright?

At the spot.

We could talk about the shop, 'cause I've been

learning a lot of shit,

and, I don't know, I feel like I got some ideas.

MIKE: Yeah, but... (stammers)

The place is no good, Carmy.

It's-it's a fucking nightmare.

-Like, trust me, I'm doing you a favor.

And I'd love to hear your ideas.

I would. I-I-I wanna hear

about you, I do.

CARM: Also I don't need

you talking to Claire

and acting all nice if you

don't actually give a fuck.

You know?

MIKEY: Wh-what?

What are you talking about

I-I don't give a fuck?

Why would you say that to me?

Carmy, I give like a... I give like a huge fuck.

CARM-Yeah?MIKEY-Yeah. fuck, yeah. I mean, I give... I-I...

I give like the biggest fuck. Alright?

CARMY; Okay.

I um, I got you... I got, uh, it's stupid.

I got you...Actually, I got you something.

-Can I give it to you?MIKEY-What, you got me a present?

CARMY: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

I got you a present.

Just one second.

MIKEY: Alright.

Wait, before I, uh... why don't you give me, like,

like, three things about Copenhagen, man?

Anything.

CARM: It's the most beautiful place

I've ever seen.

MIKEY: Yeah.

CARM: Uh... I slept on a boat.

And, uh... I fed an invisible cat.

MIKEY: Hmm. Well, Carm...that's a home run. Out of the park.

Alright, go ahead.

Go ahead, go ahead.

What is this?

Oh, Carmy, that's a...

CARM: It's like, it's like

a little bit rough,

but I don't know, it's something--

MIKEY No, man, that's... It's beautiful. That's...

That's perfect.

CARM: Yeah, Mike, we could, um... We could do this, you know.

MIKE: Yeah.

-CARMY: Yeah.

MIKEY: Yeah, let it rip.

CARM: Yeah, let it rip.

MIKEY: Yeah, Carm.

It’s a sketch of the restaurant Carmy hopes he and Michael will run together. Later, we see it framed, hanging on the wall of The Beef.

Donna calls out and Carmy leaves the pantry with the saltines. What he doesn’t see is Mikey, alone, leaning against the wall of the pantry, crying.

Season Three (originally published July 7, 2024)

Season two ends with Carmy being released from the walk-in fridge.

In Season three we find out he’s still emotionally stuck. Like his mother (Jamie Lee Curtis) he can’t bring himself to say “I’m sorry” (to Claire) and instead retreats into an obsessive focus with the minutiae of getting the new restaurant “perfect.” Is that plate at just the right angle? Are those hand-shelled peas lined up correctly? Where should I put that sprig of parsley? Why don’t the hand-crafted bowls match each other exactly?

It’s not clear what the writers’ attitude toward this culinary OCD is. In Carmy, it seems disordered, a symptom of his anxiety and dread. But all the characters, not just Carmy, fuss and fret over just where the tweezers should put this or that herb, how artfully “components” are arranged on a plate, whether the swipes of sauce leave a trace of “smudge.” The aesthetic focus is just about as far from the slapdash yumminess of the “Original Beef” sandwiches as possible, and it kind of makes everyone a little crazy. But—particularly in the last episode, in which the iconic Ever closes down—the camerawork, the music, the reverence for the art of “fine dining,” the mourning of its possible passing (there’s a “funeral” for the restaurant)—cast a glow over the beauty of “perfection” that seems at odds with the “preparing wonderful food is about nurturing people” message that was conveyed so exquisitely by Sydney’s simple, buttery, potato-chip sprinkled omelette for Sugar.

One of the readers of the stack in which this review first appeared told me that this obsessiveness with perfection is characteristic of what drives chefs. She also told me that many chefs, like Carmy, come from dysfunctional families, have trauma in their histories. She was a chef herself at one point, so I yield to her expertise and experience.

But when I’m sick or tired or depressed, I want that omelette!

In any case, none of what went astray for me this season makes me love the show less. Maybe Christopher Storer was too identified with Carmy, whose relentless moroseness gets to be a little…extra (smile, dude! Haven’t you seen how gorgeous your body is in those Calvin Klein ads?) Maybe he needs a sloppy, dripping, beef sandwich. Or a bowl of my matzoh ball soup with which my daughter, picking out the odd bone, claims I’m trying to kill her. The show has my heart, and I want to nurture not demolish it.

And there are two episodes—both written by women—that are worth the entire season. They are my matzoh ball soups, but without a single bone:

“Napkins”

Written by Catherine Schetina and directed by Ayo Edebiri (who plays Sydney in the series.) It takes place some number of unspecified years before the events of the first series, and is Tina’s “backstory” of how, depressed and desperate after weeks looking for a new job (she’s been laid off after 15 years working the office at a candy factory) happens on the Original Beef. There she walks into the chaos that Carmy inherited after Mikey died and left the store to him—people screaming at each other, laughing, throwing wrapped sandwiches around. There’s also Richie, whose warmth with customers—an ability that Carmy never does adequately value—is evident and who gives the weary Tina coffee and a free sandwich (“an Italian French dip,” he explains to Tina.) She wanders into the back room where Mikey (John Bernthal) is trying to get Neil Fak (Matty Matheson) to stop playing video games and help putting the napkins in their holders. At the first bite, Tina—too overcome to eat and possibly melting down over the little bit of kindness the sandwich represents—can’t hold back her tears. And Mikey notices.

It’s hard for me to describe what the re-appearance of Mikey did to my feels. Both Mikey and their mother Donna haunt not only the characters but the series. They are the unseen-at-first onions whose layers are peeled back, in a minimum of appearances (three of them flashbacks) that reveal, economically and precisely, everything you need to know about them and both the dysfunction and love that war with each other in the family.

What you see in “Napkins”—Mikey’s sweetness, sadness, attentiveness, and vulnerability, as he and Tina share stories and Mikey ultimately offers Tina the job that will change her life—is heartbreaking. Heartbreaking because we know his depression, at that point still being battled by his capacity to care, love, and experience pleasure, is going to win. Heartbreaking because he shows Tina a picture that Carmy has sent him, and is so full of pride over his brother’s talent—a pride Carmy craves and never realizes he has. Heartbreaking because as for so many and despite his gifts, so obvious to us, he’s never believed the “dream” was going to happen to him, but rather that he would get “skipped.”

“Napkins” has the novelistic feel that made season 2 so great. It’s not so much an episode in a tv series as a chapter in a saga—the chapter of how Tina got to work at The Original Beef, intertwined with the unfolding revelation of who Mikey was. Virtually every episode of season 2 was like that—each devoted to a different character, each diving deeper into their past and personality, what made them who they are.

“Ice Chips”

Another superb episode is “Ice Chips” (written by Joanna Calo and directed by Storer,) in which Sugar, unable to reach any of her other relatives and friends when she unexpectedly goes into labor, reluctantly calls on her mother Donna to be at her side. Donna is still pushy and at times impossibly self-oriented, but she’s thrilled to be there with her daughter, and as the episode progresses, we see the psychological clutter and barriers that have grown between mother and daughter dissolved—for the moment at least—by the simplicity and absolute priority of Sugar’s needs and (to the amazement of both of them) Donna’s ability to actually take care of her. In that hospital bed, returned to a much early form of their relationship (baby needs; mama feeds) the moments when Sugar wants Donna to just go away please!!! dance with and ultimately give way to the moments when she only wants to rest her head against mommy (who, as it turns out, does have a few good tips on how to deal with labor pain.)

This brilliantly written episode not only takes us deeper into the complexity of Donna, but also illustrates how much the failure or success of relationships hangs, not on what the other gives us, but on what we feel we’re able to give the other. And how much the two feed off each other. Carmy can’t tell Claire he’s sorry because he feels like he’s failed her so badly. Donna can’t go inside “the Bear” restaurant on “Family and Friends” night for the same reason; she’s failed her kids and can’t trust herself to not do it again.

So long as they are stuck in the conviction of their own failure, nothing is going to move. For other personalities, it can be simpler. “Just say ‘I’m sorry,’!” Neil Fak tells Carm. “Just come inside!” Sugar’s husband Pete tells Donna (returning to the table, he weeps over a dysfunction he can’t understand but that hurts him so much, for his wife.) But they are simpler souls than the Berzatto’s; loving comes easier to them.

Tolstoy: “All happy families are alike; Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

How anyone could call THE BEAR a comedy is unfathomable. I doubt I laughed even once. Your writing on this series is by far the most insightful I have read. My one bone to pick is with Tolstoy’s observation about families. Unhappy families are indeed all alike, and what they share is an inability to let family members be themselves instead of playing roles forced upon them.

Not yet- I'll look for it.

The Emmys have a broader range of categories than most award shows, given the range and variety of television programs, but it's still an adversarial, popularity based system as opposed to, say, the merit-based Peabodys.