The Existential and Economic Stupidity of the Dobbs Decision

Three years ago today SCOTUS obliterated Roe V. Wade. Their reasoning was cruel and oblivious to reality. Two excerpts from previously published pieces.

Dobbs: An Adoptive Mother’s Perspective

She was fifteen years old. It was just a hook-up at the local mall with the twenty- one-year-old ex-football star all the girls had a crush on. He left Megan with a venereal disease that took her to the doctor, where she found out she was pregnant. It was too late for an abortion, and Megan was still living with her mom, who was already struggling to raise Megan and her two other children. With a husband in jail and a single not-very-substantial income, Megan’s mom made it clear to Megan that bringing another child into the picture was just impossible. Megan understood, but being realistic didn’t soothe her sadness. In a daze, attending school with other pregnant teenagers in an RV converted into a makeshift classroom tucked behind the main high school, she submitted, feeling her fate was out of her hands.

My husband and I met her and her family three months before Cassie was born. I returned and stayed in Texas for three weeks before the birth. Cassie’s birthmother Megan and I had talked on the phone, and Megan and her mother seemed delighted with the fact that Edward and I were professors and that we wanted an open adoption, with ongoing communication and visits. But when we all actually met, at the restaurant on the ground floor of the Embassy Suites, everyone was strained and frightened. Megan, buttoned up to her chin in a demure blouse, seemed to be concentrating all her energies on simply enduring, saying “thank you” when required, and producing an occasional wan smile. She seemed depressed. She wouldn’t look at me.

She was also angry. But I didn’t know that at the time. Like most adoptive parents, I was fumbling along, looking for rules that didn’t exist for situations that I was completely unprepared for. So I relied on Megan’s mother and the doctor who had passed our brochure on to them to lead the way. They reassured me that appearances to the contrary, Megan wanted the adoption, that she liked us very much, and that she was just nervous about meeting us.

It was what I wanted to believe, so I did. And so when Megan’s mom invited us to accompany them to Megan’s next sonogram and her doctor handed that precious photo to me, I took it, weeping with joy. I took my cue not only from the doctor but also from cultural imagery. After all, hadn’t I seen moments just like this in “Immediate Family” and all those Lifetime adoption movies?1

Megan had been silent throughout the sonogram. But as soon as the photo of Cassie was handed to me, she jumped up from the table, dressed hurriedly, and ran angrily out of the office to the parking lot and into her mother’s car, slamming the door behind her, refusing to talk to any of us. I ran after her and begged her to open the door, but she remained stony and stormy, her mouth set in an expression that I have since come to know quite well when our daughter gets in an angry mood. The next day, I took her to the mall, bought her Chik-fil-A sandwich (her favorite pregnancy meal) and tried to melt the ice, with no success. My husband and I left Texas shortly after that, and waited.

This was no Lifetime movie.

The sonogram, as our adoption counselor soon found out, meant a great deal to Megan. It was for her a concrete symbol and reminder of the fact that, although she was going to relinquish Cassie to me after her birth, during those nine months she was still her mother. She wanted us all to acknowledge that. Instead, we were treating her like a pregnant child.

I had many sleepless nights after that, and not only because I was afraid Megan would change her mind. I was haunted by her loss—by the violence life had done to her in not giving her the resources to raise her baby—resources, both emotional and material, that I had in such shameful abundance. One morning, in fact, sobbing to my husband that I couldn’t take Megan’s baby away from her, I al- most changed my mind myself. I was horrified at my past behavior at the doctor’s office. I had stood there conducting transactions over the prone, semi-undressed body of a silent, sad, and withdrawn young woman, and let myself be lost in the illusion that it was all okay because she was so young.

I immediately sent the sonogram back to her, express mail, with a note of apology, and an admission of my own cluelessness. It was a turning point in our relationship. I had acknowledged the sadness she was feeling. And my becoming Cassie’s mother no longer depended on either of us ignoring that sadness.

“Less Abortion, More Adoption. Why is that so Controversial?”—Representative Dan Crenshaw, R, Texas.

So unimaginative, so callous, so oblivious to reality, right? But Crenshaw is only echoing the views of the so-called “conservative” members of the US Supreme Court, who argued, in the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, that “modern developments” such as “safe-haven” laws (which allow mothers to drop their babies off at fire-stations or hospitals without fear of criminal prosecution) have rendered abortion unnecessary.

Samuel Alito, from the Dobbs decision: “A woman who puts her newborn up for adoption today has little reason to fear that the baby will not find a suitable home.” And, not only that, but (praise be!!) she will also be helping solve a “supply problem,” as “the domestic supply of infants relinquished at birth or within the first month of life and available to be adopted has become virtually nonexistent.”

I’m always surprised to see pictures of Alito. He’s actually a few years young- er than I—another Boomer, but of the right-wing backlash variety—but in my mind he is ancient, a relic who quotes, in Dobbs, from a seventeenth-century ideo- logue who uses religious tracts to justify his position on abortion. Even more surprising—as she has both been pregnant and has adoptive children—is Amy Coney Barrett’s support for the Alito position, as she argued during the Dobbs hearings: “Both Roe and Casey emphasize the burdens of parenting, forced motherhood . . . [and] the consequences of parenting and the obligations of motherhood that flow from pregnancy—why don’t the safe haven laws take care of that problem?”

Barrett is lucky, as I was, to have been on the privileged, receiving end of the adoption experience. That privilege doesn’t extend, however, to the ability to make birthparents “disappear” entirely. In my case, Cassie’s birth relatives have had an actual presence in her life. But even when adoptive parents don’t know (or perhaps, as is the case with some, don’t want to know) birthparents, most adoptive children at some point become curious about the circumstances of their adoptions, often perplexed as to why they were “given up.” I wonder what Barrett might have answered if asked this question. Surely it wasn’t: “Well, thanks to safe-haven laws, your birthmother knew she couldn’t be prosecuted.”

And when Barrett was pregnant herself, did she regard her own body as little more than protective padding and nourishment for a fetus? Or did she expect those who loved her to be tolerant and caring of changing moods and anxieties? Perhaps pregnancy didn’t affect her at all, perhaps she simply embraced the experience of being a fetal incubator. Whatever Barrett experienced or didn’t, to assert that safe-haven laws “take care of the problem” is to regard pregnancy as a less than fully human experience, to imagine the pregnant body as a “thing” (as de Beauvoir would put it) rather than a profoundly transformed way of “grasping the world” and one’s situation in it. This is true whether one has an “easy time” or suffers constant morning sickness—or worse.

The denial of reproductive freedom is thus both existential as well as political. It’s political in that it turns women into less-than-equal subjects under the law. (No one else is ever forced by the courts, who historically prize autonomy and bodily consent, to give over their body to sustain the life of another.) It’s existential not only in the fact that it deprives us of “choice” but turns the pregnant body into a numb and mute fetal delivery system, without human subjectivity, a provider of baby “stock.”

The Dobbs decision made it clear that the same conception of the pregnant body undergirds both the Alito/Barrett attitude toward adoption and their positions on abortion. And it’s not just dehumanizing of women (and transgendered individuals who become pregnant). Actually, the babies that are relinquished don’t fare much better. Before birth, when they are still fetuses, they are virtually “super-subjects” who have rights that supersede not just the rights of their mothers, but are more extensive than those granted to anyone else in our society. Who else besides the fetus can make a claim on another person’s body to operate as a life-support system for them? Even those who decline to take simple blood tests to determine their compatibility with a dying relative whose life their donation of blood or marrow might sustain cannot be forced to. Yet after birth, the fetus loses all its super-privileges, and becomes part of a dwindling “supply,” diminished stock for the market in babies. Pump up the supply, get them placed, and forget about them.

”The body is not a thing, it is a situation: it is our grasp on the world and our sketch of our project.” —Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex Megan

However hard they try to deny us our personhood, we are humans, not things. And even the best decisions—which we all felt our adopting Cassie to be—do not magically banish loss and grief. When Megan came to visit months after Cassie’s birth, she held her tenderly and gave me a great gift: “I just love the way you and Edward talk to her.” But there were many times when I caught her gazing at Cassie with an expression that’s hard to describe. It was as though she was saying to her: “Beautiful Cassie, I wish I could have kept you. I’m so glad you have Susan and Edward. And I’ll always love you.”

Megan has since married and has two teenage children whom Cassie regards as her siblings—which they are. And if Megan had known about her pregnancy in time to have an abortion? This kind of “argument,” which gets implicitly trotted out on every anti-choice sign featuring a baby thanking her mother for not abort- ing her, is perverse. If Cassie had not been born, the entire course of all our lives would have been different, just as they would be if I had not had an abortion when I got pregnant in graduate after a reckless, ecstatic night with another student. I might have a forty- five-year-old son or daughter today, and I might be a grandmother. It’s insulting to me, to Megan, and to Cassie, to engage in this kind of hypothetical mind-game.

The reality is that Cassie, who it is impossible to imagine my life without, was born. And as over the years I recognize more and more of my stubbornness, my snarkiness, my iconoclasm, and my tender-heartedness in her, I also see Megan’s shyness, and the physical power and presence of her birthfather (who disappeared from the scene, as many birthfathers do, shortly after Cassie’s birth). She is my daughter, but they live in her body and through her body will forever shape her grasp of the world, her situation in it, and the “project” of her being.

We make choices, and our lives issue forward from them. That’s the right— and the burden—that comes with being human.

****************************************************************

A longer version of this was originally published in a special edition of Adoption and Culture: “We All Grieved: Abortion, Adoption and the Callous Indifference of Dobbs”

“Economics”and the Gender Gap on Abortion

(An excerpt from a stack that I published on September 24, 2024 as part of my “Election Watch 2024.”)

In a recent television appearance, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer highlighted an all-too-often unrecognized reality: reproductive rights are an economic issue – and not only for women. “The most important, profound decision a person will make, especially a woman, or family, is whether and when to bear a child,” she noted. “So, this is about our personal economy. This is about our collective economy. How can women get into the workforce if they cannot make their own decisions about whether or when to bear a child or access health care?”

Whitmer is absolutely right. Too often, the press and voters treat abortion, and reproductive rights more broadly, as well as other “family” issues – like child tax credits, paid family leave policies and affordable childcare – as somehow different from economic issues. But they are not. All of these issues have significant long-term economic consequences for women, for their families, and for the economy.

(Laura Tyson, “Abortion and Reproductive Rights are Economic Issues,” in Project Syndicate, September 20, 2024)1

For years among feminists I was fairly alone in pushing reproductive freedom as a social and economic equality issue. The dominant feminist arguments generally stopped short after the word “choice.” So I was delighted when Stacey Abrams, in her 2022 run for governor, declared that reproductive rights “is an economic issue.” Responding on Morning Joe to Mike Barnacle, who conceded that abortion is “an issue,” but “nowhere reaches” the importance as the price of food, gas, or housing, she insisted that caring for children is why we worry about food, gas, and housing. And since women are the ones who bear children, for women, “this is not a reductive issue. You can’t divorce being forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy from the economic realities of having a child.”

Unfortunately, the message didn’t get through. Among other explanations for Abrams’ loss is that her “platform tended to highlight issues of concern to women voters.” Whether true or not, it was the perception among men, including Black men. that she was focused on “women’s issues” like abortion. Not on “the economy.”

Unplanned pregnancy, it’s true, has the most proximate economic consequences for women, who may be forced to quit jobs, halt progress toward higher education, or eschew jobs that offer greater possibilities for promotion and higher pay but require “grueling, unpredictable schedules” But every limitation on a woman’s ability to bring income into the family also places a greater economic burden on husbands and partners. The burden may be mitigated if one can afford child care or has it provided at work, but it rarely is. So it’s no surprise, as Tyson outlines in blistering detail, that “there are strong links between poverty and abortion – denying access to abortion places the greatest economic burden and significant health risks on low-income, often minority women, increasing both poverty and inequality.”

Alito and the others who decided Dobbs were well aware of studies that showed the economic consequences of their decision. They simply chose to ignore them, pretending to be “pro-family” while in reality they were only “pro-fetus.” The same has been true of the elected leaders who have introduced and promoted the cruelest, most draconian abortion bans: “They wrap themselves in pro-family rhetoric. But the reality is starkly different. In the states with the strictest abortion restrictions, children are more likely to be poor, and babies are more likely to die in their first month. Additionally, women in these states experience higher maternal mortality rates and are less likely to complete their education”.

All of this means reproductive “issues” are issues for men as well as women—and not just because of their emotional ties with women and girls, which have tended to be emphasized in men’s “pro-choice” movements, but because insofar as the economic well-being of families is not dependent on their earnings alone, what happens to their female wives and partners matters to their economic well-being too.

I wish more men saw it this way. If they did, we might not have the huge gender gap that has been widening (with a few ups and downs) since 1980 and that currently is, as Steve Kornacki put it, “off the charts,” with Harris leading among women by 21 points and Trump leading among men by 12. That’s a 33-point gender gap, the biggest in electoral history. And while the enthusiasm of women for Harris—which may, for the first time, cut across party affiliations and bring white Republican women into the Democratic camp—is enhancing her chances of a huge popular victory, the male pro-Trump factor may be a problem in clinching an electoral victory—the one that counts, unfortunately—for her.

The men that prefer Trump do so for a variety of reasons, including garden-variety sexism, and the fact that “Republicans have stolen the reputational space of strength and masculinity while Democrats own the existence as the party that is more sympathetic to those who need help and their nurturers.” Racial factors enter in, too; In describing where the Democrats consistently “overlooked” Black men’s issues, Phil Agnew, director of “Black Men Build,” points to the Democrats failure to address the disproportionate incarceration of Black men, the lack of “working-class” jobs, and the special importance that Black men, vilified by stereotypes, attach to being able to support a family. Some continue to see Harris as The Prosecutor.

But: There’s also that perception that dragged Stacey Abrams down, that Harris’ policies are “geared to women and children”—while Trump is more focused on “the economy.” As though they are competing priorities rather than thoroughly intertwined, as Abrams argued.

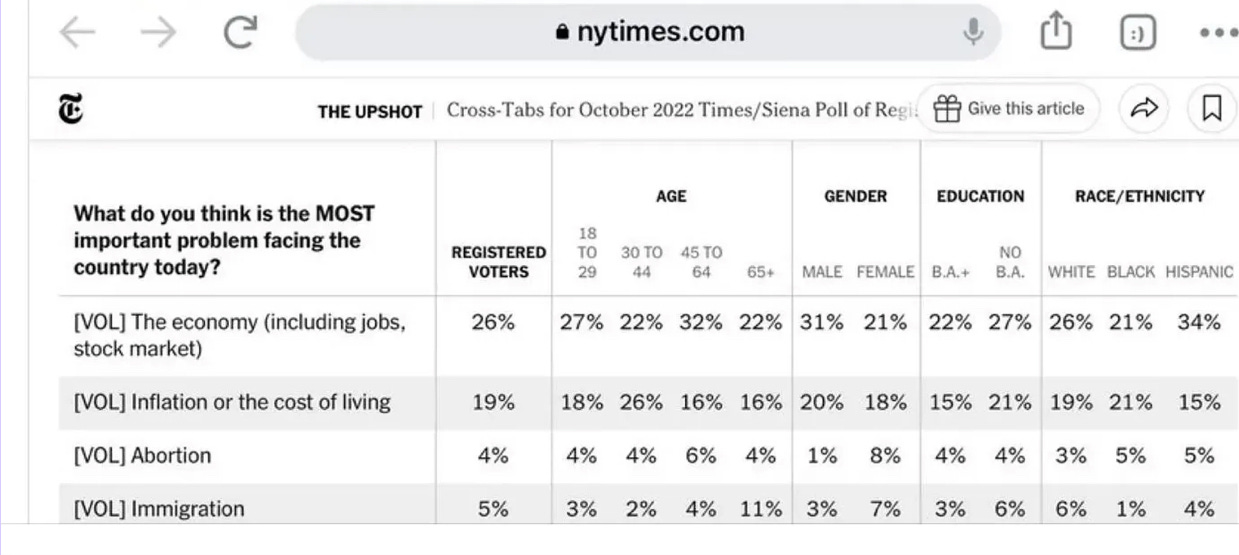

Let’s note first of all that choosing ONE “problem” (out of about 25 listed; I’ve only screenshot the top four) forces people to prioritize one issue from many that may be EQUALLY important and in fact, are intertwined rather than separate.

As I argued earlier, lack of access to abortion is an “economic problem” for the families who can’t afford another child, right?

Not according to this poll. “The economy” is specified as including “jobs” and the “stock market” and that’s it. But why is “the economy”—but none of the others—given specificity at all? And why “the stock market”—rather than, say, “health care”? Access to health care surely affects most people’s economic lives as much, if not more, than the stock market. Moreoever, specifying the "stock market" within "economy" is arguably biased toward the priorities of wealthy responders.

Note also that “the economy” and “abortion” are listed as though they are parallel types of items. They’re not. Listing them as such is what philosophers call a “category mistake.” “The Economy” is an umbrella term which can be interpreted to include virtually any aspect of life that has economic consequences. “Abortion” is one aspect of reproductive health (alongside contraception access, pregnancy care, IVF, medical assistance during miscarriages, etc.) and abstracting it in this way encourages people to think of it (unlike the all-embracing “economy’s”) as a “single issue” problem. This construct is biased toward choice of "the economy" as "most important,” even among respondents who care very much about reproductive freedom.

I’ve always found “the economy” a problem term. So vague, yet so loaded—as so many aspects of people’s lives can fall within that rubric, and commentators in the media tend to glom them all together under that one category.

Inflation/recession trends. Growth of jobs. Price of eggs, Deficit. Whether you can afford to buy a house? How much poverty there is? Whether families can afford childcare? Whether they can afford the meds they need? Just a feeling that it’s something a “businessman” is best able to handle? Something you remember was once “better” but can’t really say in what way?

Seems like there’s a whole bunch of different points of reference floating around out there. Yet the polls and pundits and the people they query keep insisting “the economy” is “the most important thing” without any precision as to what they’re talking about. And since the Republicans have managed to convince so many people that they are the most trusted keepers of “the economy” it of course gives the GOP a special edge—even when, as has been the case over the last 4 years, the Democrats have actually done a far better job in any and all of the “sub”-categories.

Why is the poll construction important? Polls don’t just ask for your responses; through the way the questions are phrased and constructed, they also give you instruction in how to think about the issues. Sometimes the bias of the instruction is far from subtle, as you’ll see if you have a look at the stack I referenced earlier. Other times, it’s more covert, as in the privileging of the GOP’s favorite talking point: “the economy” (defined, once again, as jobs and the stock market) over issues that are more likely to be seen as less important—because “single-issue”—priorities. Like “abortion.”

In March of 2008, Barack Obama gave a speech on race (also called his “more perfect union” speech.) Although it’s since become part of Obama’s legacy of great oratory, the then-senator’s speech was actually a campaign event, written to explain to the nation why he couldn’t simply disown his long-standing relationship with pastor Jeremiah Wright, Jr., whose antisemitism and inflammatory rhetoric (blaming the U.S. for 9/11: “God damn America”) almost derailed Obama’s candidacy. Meeting the crisis head-on, Obama delivered a 40-minute, nationally televised speech that situated the controversy both in his personal history and Black history and community.

It was spectacular. And it alchemized a potential disaster into a deeply educational, inspirational moment.

Kamala Harris’ speech on Saturday in Georgia was as brilliantly argued, artfully delivered, and emotionally rousing as any speech I’d ever heard. Yet it was presented by the media as just “another stop” on her “reproductive freedom” tour. There was no commentary on her skill at weaving together personal experience, the heart-shattering case of Amber Nicole Thurman and the history, contradictions and outrages of the Trump abortion bans.

I’d like the corporate media to give Kamala her 40 minutes of nationally televised brilliance of heart and mind to widen voters’ perspective on reproductive issues. To situated them not only in the broader, more diverse context of “women’s health”—which she is already doing in speeches like the one she gave in Georgia. But also: As having consequences for the well-being of children The ability of families to thrive. Our progress toward racial, legal and economic equality.

And because of all that, they are men’s issues too.

For more from me on reproductive issues see:

“Right Up To The Moment of Birth” Really??

I watched the GOP debate last night. I didn’t expect anything different from what I got. But I did expect better from post-debate commentators. I’m perplexed that although there has been plenty of outrage over the raising of hands raised in support of voting for a convicted felon, I’ve yet to hear any corrections of the lie—repeated over and over by ev…

Works Cited

Alito, Samuel, et al. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. US Supreme Court, no. 19-1392, October Term 2021, 24 June 2022. www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pd- f/19-1392_6j37.pdf.

Bordo, Susan. “All of Us Are Real: Old Images in a New World of Adoption.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 21, no. 2, 2022, pp. 319–31.

Crenshaw, Dan. “Less Abortion, More Adoption.” Twitter, 2 May 2022, 11:34PM. twitter. com/dancrenshawtx/status/1521332386184769541.

de Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. 1949. Vintage, 2011.

O’Dwyer, Jessica. “Amy Coney Barrett’s View: Adoption, Not Abortion.” Opinion: Letters.

The New York Times, 18 Dec. 2022. www.nytimes.com/2021/12/18/opinion/letters/ amy-coney-barrett-abortion-adoption.html

Thanks for this, the personal and the political. Economics, after all, is fundamentally a political discipline: who pays, and who receives. "All the rest is commentary."

At this moment, Trump has just bombed Iran and the military is reveling in its gargantuan success. We think of other nations is bullying, but in fact, we’re the bullies, and have been bullies for a long time. In addition to our huge military with gargantuan, buster bombs and tanks…made obsolete byUkraine’s drone attack on Russian aircraft. We have 800 military basis around the world. The last I looked, we were not at war with anybody, but if you have a military that size you’re gonna be flexing your muscles and going for it. In addition , at this moment, we have a president who thinks everything he does is right. He’s an immoral, irresponsible, uneducated sociopath, and we are letting him run the nation. But mainly he’s being run by the men of this nation. Men who haven’t the courage to see what he’s doing, is destructive to everything moral, responsible, or desirable about this country.

Even the abortion issue is a ploy to get people to vote Republican. Evangelicals were fine with Roe for seven years until the IRS reverse the tax exempt status of Bob Jones University for not admitting blacks. Then evangelicals looked for an issue to get people to vote Republican. They found that abortion would do the trick. Nobody cares about the unborn. It’s about getting people to vote Republican.

Thanks for your thoughtful remarks,Sumter Carmichael Coleman