This Week on “Perry Mason”: Della’s Perry Mason Moment

Ms. Street shows her stuff, Paul continues to stew, and Perry messes up with Ginny

While watching “Perry Mason” this week, and especially during the scene with the seagulls and the oil-covered fruit, I kept thinking about that great 1974 neo-noir movie “Chinatown”—also set in Los Angeles in the 1930’s. In 2023, we think of California as a sunny haven of progressive politics, but movies like “Chinatown” and “Mulholland Drive”—and now, the “Perry Mason” series—remind us that it once was a kind of coastal “wild west”: no cowboys or cattle round-ups but plenty of political scheming, shady land deals, and unsettled social structures. Besides the plot involving the corruption beneath the facade of establishment politicians and business people, there are wonderfully sinister motifs in every episode: a pair of converse sneakers, the laces drenched in blood, hanging off a telephone line, voracious seagulls pecking at each other while tearing at rotting fruit, close-ups of the birds’ nervously darting eyes, a little girl’s Sunday-best white shoes, smoldering and then consumed by fire. The series even manages to make close-ups of a one-hundred-dollar bill, rolling though the ending credits, appear creepy and dangerous. Each one of these images is unprecedented and surprising, transforming the ordinary into the unnerving and foreboding. I love it.

I also love the brooding Paul Drake, who is rightly haunted by his having beaten up another Black man who was, like him, only doing what he needed to do in a society that doesn’t make legitimate jobs easy to come by if you’re Black or Mexican. He’s the most “interior” character in the show—that is to say, his face is never in repose, his inner struggle (“Am I good?”) is always written on it. The strain of it makes him raw and quick to anger at wife Clara and her brother. Perry is a hot-head; his outbursts are in character. But Paul is a steady, controlled man, and the suppressed turbulence in him—the cause of which he is ashamed to admit to his wife—explodes in startling ways. When he snaps at Clara—“Just mind your own business right now!”—it’s such a break from the thoughtful, if distracted, husband we’ve seen up until then that it’s almost as though he’s become a different person. He knows it too. “Let’s just get back in line,” he says, seeing her face, trying to forget the guy in the line who’s wearing converse sneakers.

In past posts about “Perry Mason” I’ve talked abut the pleasures of how the show “breaks the mold” of various film and tv cliches. It continues to do that—for this most part. But this past week, for the first time, the series had a (hopefully brief) regression into a familiar trope. Someone has leaked the information about the murder weapon that Perry has hidden in his office wall safe—and after questioning Della and Paul about whether they’ve shared info with Anita and Clara (they are appalled that he would go there, and they are right to be) he remembers that his new girlfriend Ginny had come to the office when he and Della were discussing the case. Ignoring their shared intimacy and everything he believes about Ginny up till then, he bursts into her apartment and accuses her. Convinced she’s the traitor, he won’t even give her a chance to defend herself, and leaves her in tears. For all I know, he may turn out to be right. (We know Strickland had tried to get into the office, but he failed, and someone else—we only see the shadow of a—perhaps—feminine-looking arm—succeeded later.) But I strongly suspect Perry is going to regret it—and that seems to be confirmed by by something Matthew Rhys says in the post-show mini-documentary. (You’ll find it—called “Eyewitness Account”—further down in this post.) Whether or not Perry is right, for the first time this season, I felt as though I’d seen all this many times before: the rush to judgment, the hot-headed accusations, the mistake that breaks a promising relationship. (Think Sally Field and Paul Newman in Absence of Malice as one example.) I know Perry is impulsive, and has little trust in people in general. But his stony refusal to even listen to Ginny just didn’t jibe with his character, at least not for me. The scene felt contrived—and too-movie familiar. Let me know what you think!

The star of this weeks show was Della, Della, Della!! You did us proud, grrrl. And made those who’ve been longing for more courtroom drama in the series very happy. Last week, Perry had his moment when he showed that Rafael’s fingerprint on Brooks McCutcheon’s steering wheel had to have been planted. This week, Della, in a scene that had even the extras in the courtroom spellbound, proved that it was not a car accident that had caused the brain injury that reduced Councilman Taylor’s sister Noreen to a “shell of a woman,” but Brooks’ belt, tightened around her neck during sex. In so doing, Della gave us the first big confession scene that the older series was famous for. She doesn’t shy from being explicit in an interrogation that Perry could never have handled as a man, without turning the jury against him.

“Brooks McCutcheon liked to surprise women during coitus. He would put his belt around the woman’s neck, like so, and then he would begin to tighten it. And he would not let up until he wanted to. Even if the woman was desperately gasping for air. Which was your sister’s case, wasn’t it?”

As Della says all this she enacts being on the receiving end of the tightening belt.

“So…what honestly happened to your sister? And I’d like to remind you, you’re under oath.”

Taylor (low voice): “She was strangled.”

Della: “Pardon?”

Taylor (louder this time, and visibly upset): “She was strangled.”

Della: “You must have hated Brooks for what he did. Turning your vivacious sister into a shell of a woman.”

Della then goes on to remind Taylor of something he’d said at a party: “I’ll kill the perverted bastard.” When he says he never said that, she asks him what he did say. Taylor: “I don’t remember.” Della: “Like you didn’t remember Brooks strangled your sister?”

It looks like they may have the reasonable doubt that they need to point a finger at someone other than the Gallardos. But then there’s the gun discovery, and as Juliet Rylance has put it, the roller-coaster is back in operation, plunging downward at the end of the show.

In an earlier post on this series I said that you can always tell when women have had a hand in the production of a movie or tv series. The post-show “Eyewitness Account” feature, besides providing fascinating information about the rigorous historical research that went into the plot-line (and revealing what Juliet Rylance and Matthew Rhys actually sound like!) showed us just how large a role women (producer, researchers, writers) have played in the series. Not that the show preaches a feminist message. It doesn’t have to. The care and sophistication that have gone into the female characters does that work for it.

This got me thinking about other portrayals of female lawyers, and how Della departs from them.

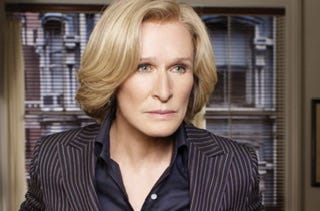

One familiar archetype is the “fierce” female lawyer, exemplified by Glen Close in “Damages” and Viola Davis in “How to Get Away With Murder.”

These shows are tremendously entertaining; it’s fun to see women wielding power and feeling no shame about it. It’s also a genuflection to the iconography of masculinity, as do the portrayals of many fictional policewomen and investigators. And these bold women are often made to pay for their fearlessness with sexist colleagues, ungrateful children, romantic problems, and other obstacles to happiness. Carrie Matheison (Claire Danes) of “Homeland” is bipolar and so driven by her work that by the final season she seems to have totally forgotten she has a child. Jane Tennyson (Helen Mirren) of “Prime Suspect” is an alcoholic with a crappy love-life. And so on.

At the other end of the spectrum, “The Closer” and its spin-off “Major Crimes” are careful to feminize their female leads: Brenda Leigh Johnson (Kyra Sedgwick) has a honeyed Southern accent and quells her anxiety with candy that she keeps hidden in her top drawer; her successor, Sharon Raydor (Mary McDonnell), is soft-spoken and serene to the point of other-worldliness. At the height of “third-wave” feminism, we also got Ally McBeal, which ran from 1997-2002 and made a point of rejecting the notion that a woman lawyer has to be aggressive and forceful in the courtroom—and identified that kind of thinking, derisively, with an “old-fashioned” and defunct feminism. The show had nothing but scorn for what it presents as “second-wave” issues and attitudes. Ally (Calista Flockhart) flirts with male clients without any thought to sexual harassment laws, and watercooler talk with the men about penis size is not only ok, it’s practically obligatory to demonstrate that the heroines are not those kind of feminists. You know, the kind who don’t wear make-up and can’t take a joke.

As a “career girl,” Ally was a mess, who can’t even hold her shit together at the sight of an attractive male. In fact, any kind of excitement makes Ally lose her cool. When she gets angry, she screeches like a little child having a temper-tantrum. When she’s upset, she sputters, stammers, and (as she so adorably admits) generally lose control over the English language. Of course, we’re talking about a comedy show here. Still, for some critics, Ally’s dishevelment (and her immature Lolita-body) was a “slap in the face of the real-life working girl” who makes “male power and female powerlessness seem harmless, cuddly, sexy, safe, and sellable.” For others, the show hits a cultural “nerve” in depicting the confusion and self-doubt that many women feel has been air-brushed out of the advertisements of the hyper-competent, ambitious working woman. For myself, I watched and enjoyed Ally, even when I wanted to smash her face. But she belongs to another era. It’s difficult to imagine anyone selling a show today in which male power and female powerlessness and/or incompetence are seen as “cuddly” or harmless.

There’s a whole other kind of fictional female lawyer, though. She’s feminist, but non-ideologically. She neither tries to be like men nor does she play off her femininity. She’s composed in court and won’t back down, but after work can get a drink with her adversaries. She recognizes the inequities of gender, but the show doesn’t punish her (with a lousy love-life, for example) for her ambition. “The Good Fight” is a prime example. A spin-off from the successful “The Good Wife,” the show neither disowns “second-wave” feminist politics (as in Ally McBeal) or takes marching orders from it, but shows just how much more complex professional women are than as painted by the stereotypes—whether they come from the Right or the Left. Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski) is glamorously long-legged in her absurdly glittery power-suits—hard to believe a real lawyer would dress as if going to a Broadway opening—but good-natured and tolerant in her relationships. Neither “shrill” nor silent, she likes to laugh—but she’s also often the “adult in the room,” quietly thoughtful when discussion deteriorates into squabbling. She despises Trump and for a while, disgusted by the fragmented, ideological chaos of Democrats, participates in an all-female radical resistance group. She’s unwilling to follow them, however, when they propose mucking around with voting machines. She’s open about her own feminist politics but married to a Republican ballistics expert (Gary Cole.)

The other women are complicated, too. They all have romantic lives, But it’s the characters’ brains rather than their relationships that are highlighted. From named partners Lockhart and Liz Reddick (Audra McDonald) to associates Lucca Quinn (Cush Jumbo) and Maia Rindell (Rose Leslie), to aspiring investigator Melissa Gold (Sarah Steele) are really, really smart. None of them neatly satisfies any gendered or racial stereotypes either, which is in keeping with the show’s refusal to partake in white liberal self-congratulation even as it relentlessly skewers Trumpism. “People who make history and do good are complicated,” Diane says in one episode, not so much in defense of the behavior of the firm’s founder, who had sexually exploited his secretary and stenographer for years, as against the politics of purity, whether evangelical or left-leaning. In another episode, when a “progressive” young woman who runs a website called “Assholes to Avoid” berates her (and her entire generation of feminists) for being too soft on men, she replies, “You know what your trouble is? You think women can only be one thing.”

“The Good Fight” wasn’t the first, though, to smash our archetypal expectations.I don’t know how many of you—unless you are film buffs—have seen “Adam’s Rib.” Written by Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin and starring Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracey, the movie is a great reminder of the fact that before we entered the post-war infatuation with a “return” to traditional gender roles Hollywood gave us some amazing, stereotype-busting portrayals of women. (This 1949 film is just on the cusp; it came out the same year as “Father of the Bride,” a film that exemplifies the idealization of the suburban family.) When I taught film, I always began with a couple of films that disrupted my students’ notions about gender and the not-always progressive “arc” of history. “Adam’s Rib” was at the top of that list:

In closing, hope you enjoy this clip (below the “share” and “subscribe” buttons) from “Adam’s Rib” and may be inspired to see the whole movie. (if you haven’t already.) And I’ll see you next week!!

Great!