Three Lolitas

First was Nabokov's Lolita, then Kubrick's, then Lyne's. Is it possible to imagine a remake today? Would I even be allowed to teach my course without the MAGA cops storming my classroom? Let’s talk!!

To my delight (and amazement), I was elected in 2023 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Being elected was the biggest surprise, but second to that was the category I was elected to: “Literature and Literary Studies.” I actually don’t fall neatly within any disciplinary category but I’ve never been a professional literary scholar. My degree is in Philosophy, but most of my published work has been in what could be called (for want of something crisper) interdisciplinary cultural studies. Within that rubric, I have done some literary criticism—but always within a broader cultural context. I particularly love looking at how movies and tv have interpreted and reinterpreted famous novels. And I especially loved teaching courses organized around those texts.

One of my favorite courses was on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, the two movies based on the book, and cultural archetypes (in fashion, for example) of “the nymphet.” I’ve rarely had such engaged students as in that course—which I taught both as an undergrad and a graduate seminar.

My teaching, as was often the case, generated some writing. I wrote a piece about “The Moral Content of Nabokov’s Lolita” for an academic collection, and a chapter on “Humbert and Lolita” for my book, The Male Body. But my first publication on Lolita was a 1998 Opinion Piece for The Chronicle of Higher Education, and it was largely about Adrian Lyne’s movie, which was just then coming out.

Looking at the piece now, I’m wondering what a new movie of Lolita would look like. Or could look like! And would I run into problems even teaching the course? On the one hand, since #MeToo, we’re much more aware of and sensitized to sexual abuse (sometimes to a fault, as I’ve argued elsewhere, seeing any kind of uninvited touching as a species of abuse.) But also, in 1996 the armies of the Right had not yet begun to wield the power over the classroom and curriculum that they are attempting to now.

Below is the original essay. Let me know what you think about the above issues or any other questions, comments, or experiences that the piece brings up for you. Share! Talk! Let’s have a “classroom” discussion.

True Obsessions: Being Unfaithful to ‘Lolita’

Originally published JULY 24, 1998

On August 2, the Showtime cable network will broadcast Adrian Lyne’s film Lolita, and in late September, the movie will be officially released in theaters. Like the publication of the novel on which it is based, the public premiere of the movie is a long-awaited, controversial event. The film was spurned by U.S. distributors for nearly a year while it played in various cities in Europe, and Lyne complained of the tyrannies of political correctness in America. He proudly pointed out that Nabokov’s novel, published in Paris in 1955, also had to wait for acceptance in the United States.

When Nabokov’s Lolita was finally published here, in 1958, many reviewers were baffled by the reputation for prurience that had preceded this story about a middle-aged man’s sexual infatuation with a 12-year-old girl. Elizabeth Janeway, in her 1958 review of the novel for The New York Times,described it as “one of the funniest and one of the saddest books” she had ever read. “Humbert is all of us,” Janeway declared -- meaning that we all have the capacity to become lost in our fantasies and to forget the real person in front of us.

Forty years later, the proclamation that “Humbert is all of us” is even more apt than it was in the late ‘50s. Nabokov was an artist, not a sociologist. But with his keen eye and ear for detail, he now seems uncannily prescient in giving Humbert a taste for undeveloped, coltish beauty, which is hardly an eccentricity anymore. For many people today, the very word “Lolita” denotes not a character in a novel but a familiar female archetype. “Precociously seductive girl” is Webster’s definition -- and images from the fashion world have given the archetype a visual form. Humbert/Lolita relationships are the topic of talk shows, memoirs, and debates among scholars and therapists.

With all of these cultural layers, it’s a challenging time for Lyne to have made a new film of Nabokov’s story (an earlier movie was made by Stanley Kubrick in 1962), and an important moment for us to reassess the novel’s relevance to our lives.

Lyne, whose past credits include Flashdance, Fatal Attraction, and Indecent Proposal, has said that he was haunted by the novel and wanted only to be “honest” to it. But he seems to have had some difficulty separating the cultural archetype from Nabokov’s creation. In one scene in his film, Lolita (Dominique Swain) creeps across the floor, murmuring sexual enticements (“You like that. You want more, don’t you?”), then lasciviously strokes Humbert’s (Jeremy Irons) inner thigh. When Humbert rapes her, inflamed by the sight of her sitting on the motel bed, her lips smeared with scarlet, apparently having returned from a date with another lover, she alternately cackles wildly and swoons with pleasure at his rough treatment.

Viewers unfamiliar with Nabokov’s masterpiece (or whose memory of the book has been dimmed by time) are unlikely to recognize that Nabokov’s Lolita never behaves like this. I was shocked, however, to find that movie reviewers, who’ve presumably read the novel, have without exception remarked on Lyne’s fidelity to it: a “lavishly faithful production” (The New York Times), “almost debilitatingly loyal to Nabokov’s novel” (The New York Review of Books), “careful, even loving, loyalty to the book” (The New Yorker).

I have to wonder what novel these highly literate journalists have read -- Nabokov’s brilliant, precise, non-demonizing but unsqueamish dissection of pedophilic desire, or a newly discovered collection of Humbert Humbert’s untrammeled fantasies?

This isn’t to say that Nabokov’s Lolita is an angel. She taunts and sulks and flirts; she has a smutty mouth. She’s careless, experimental with her body. Humbert was “not even her first lover.” But sex with adolescent Charlie (at summer camp) had “hardly roused” her; she thought it was a kid’s game, “part of a youngster’s furtive world, unknown to adults.” Lolita had done the deed, but her sexual consciousness was still that of a child. And so it largely remained with Humbert, a detail that Steven Schiff’s “faithful” screenplay manages to avoid. In the novel, Lolita was Humbert’s “frigid princess,” who invariably preferred a hamburger to “a Humburger” and at best would tolerate his caresses when promised money or presents. “Never did she vibrate under my touch,” he recalls.

For Humbert, who is revolted by the “pitifully ardent” passion of mature women, Lolita’s sexual diffidence is a large part of her appeal. “There she would be,” he recalls fondly, “a typical kid picking her nose while engrossed in the lighter sections of a newspaper, as indifferent to my ecstasy as if it were something she had sat upon, a shoe, a doll, the handle of a tennis racket, and was too indolent to remove.” Lyne and Schiff take this image of Lolita reading the funny papers, oblivious to Humbert’s mounting passion, and convert it into an atmospheric, hazy, sun-streaked romantic idyll in which Lolita, sitting on Humbert’s lap, is overcome with sexual excitement and appears to have an orgasm.

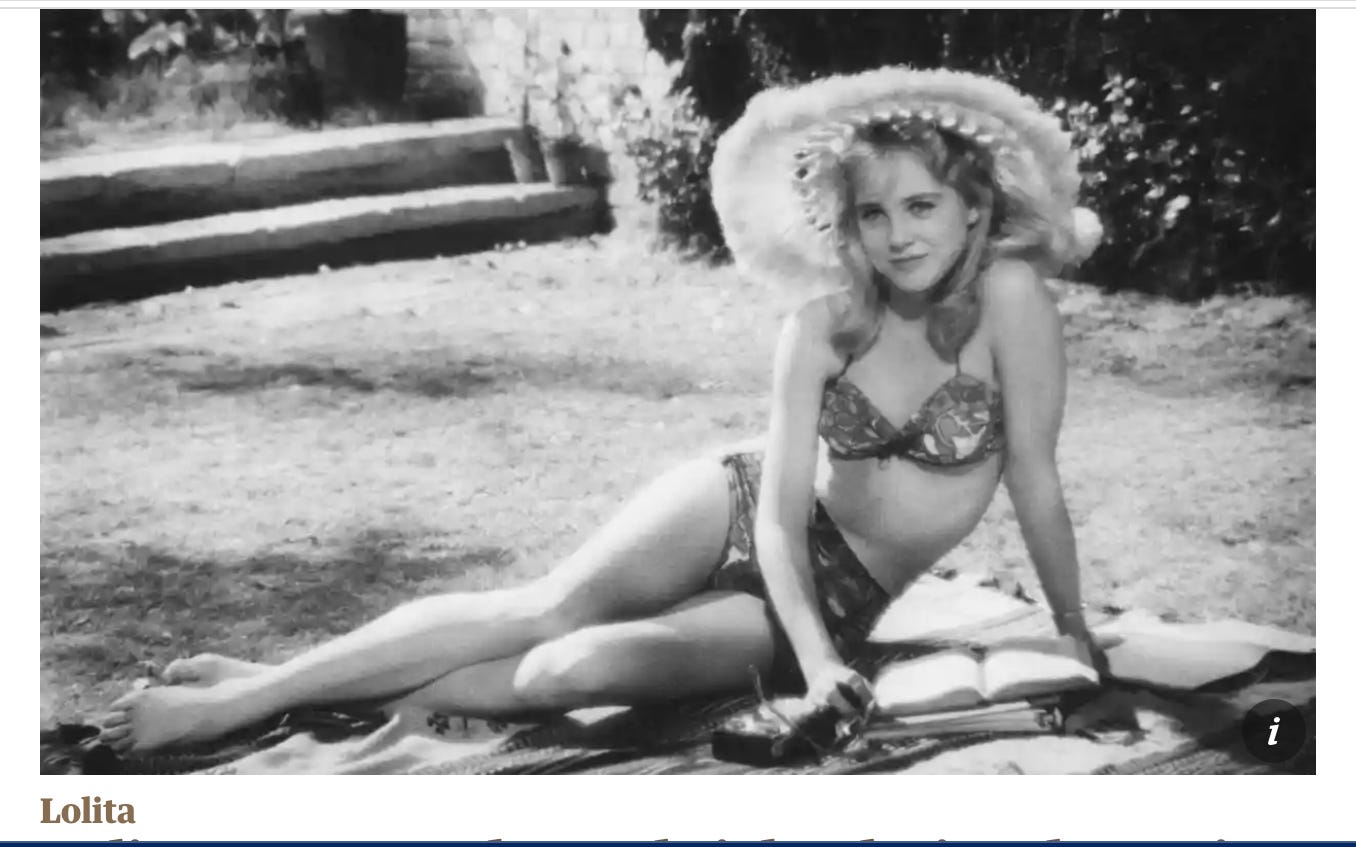

The sexual maturation of the character Lolita began with Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film, and the strategic choice of the curvaceous teenager Sue Lyon for the title role.

In the book, Humbert is drawn to Lolita’s 12-year-old body, with its “narrow white buttocks” and “puerile hips,” its “thin, knobby wrists” and “beautiful boy-knees,” precisely for its immaturity. He’s repelled by “that sorry and dull thing, a handsome woman,” and views even the “average coed” (with her “heavy low-slung pelvis” and “thick calves”) as a “coffin of coarse female flesh.” Employing a 12-year-old actress was out of the question, but so too was using an actress who even looked like a 12-year-old. We were still pre-Twiggy in 1962, and an undeveloped female body, Kubrick feared, would scream to the Production Code Administration: “This is a child having sex with a 45-year-old man.”

So Lolita’s cinematic history began with a major distortion of the title character. Sue Lyon’s Lolita -- her “literary” age upped to 14 -- had a body that looked like it had been enhanced by estrogen for some time. Take the gum out of her mouth and she and James Mason are a pretty attractive couple. (The Humbert of the novel, however, would probably have found Lyon too feminine to be desirable.)

On the face of it, Lyne’s film seems to have broken the ground that Kubrick feared to tread. Fourteen-year-old Dominique Swain was a controversial choice for the title role. She doesn’t look as young as 12 (and Lyne, following Kubrick, has aged the character to 14), but she does have a leggy, lithe body that is more faithful to the Lolita of the novel. In 1998, her willowy shape is also more conventionally feminine -- for females of all ages -- than it was when Sue Lyon played the role. So, presumably to make her look more like a child, Lyne has loaded her with accessories ostentatiously advertising her girlhood: old-fashioned plaits wrapped around her head, retainers on her teeth, milk mustache, oversized pajamas.

Ladies and gentleman of the jury, don’t be seduced by this artfulness. Lyne’s Lolita is a child only when she’s guzzling milk in front of an open refrigerator, or crying into her pillow at night. When she’s after sex, she’s all woman. Humbert rapes Lolita in an act of fury, but there is not a single scene in Lyne’s movie in which Humbert is portrayed as the initiator of erotic relations with her.

In the book, quite the opposite is true. At the beginning of their relationship, Humbert -- terrified of “impairing the morals of a minor” -- is constantly scheming ways to surreptitiously fondle Lolita without her knowing what’s going on. The night they begin their cross-country journey, he drugs her so he can pleasure himself while she’s unconscious (a seamy little detail omitted from both the Kubrick and Lyne films). Later in the relationship, he badgers, terrorizes, and bribes her into dispensing her sexual favors. In Lyne’s film, Lolita is made to be the instigator of all that sexual bargaining.

The Schiff/Lyne film makes Lolita more sexually aggressive as a deliberate interpretive choice, not -- as with Kubrick’s maturation of Lolita’s body -- as a sop to censors. Lyne has said he wanted to portray an “evenly weighted battle of the sexes,” Schiff that he viewed Hum and Lo as “a couple -- a very odd couple, to be sure, but a couple nonetheless ... testing each other, confounding each other, and, yes, loving each other.” He certainly succeeded in confounding Michael Wood, who wrote in The New York Review of Books that the orgasm scene in the movie “seems relatively healthy, since it’s only sex, and both are enjoying themselves. I know it isn’t healthy, and I don’t think it is once I remember her age. But I have to make myself remember this.”

He wouldn’t have the same reaction if he went back to read the book. The idea of Hum and Lo mutually pleasuring each other (The Joy of Sex, perhaps, on the bookshelf behind them) is utterly at odds with Nabokov’s depiction of the relationship, which never lets us forget that Lolita is a child, and that it is Humbert’s fantasy-nymphetology, entangled with memories of a childhood love, that endows her with sexual power.

Humbert sees Lolita as an “elusive, shifty, soul-shattering” charmer around whom no man can be safe, a “deadly little demon” of “fantastic power.” So, it would seem, does Lyne. But Nabokov, while sympathetic to Humbert’s memory-driven obsession, doesn’t fall for Humbert’s engorged view of Lolita’s power. Instead, Nabokov continually draws attention to the disjunction between Humbert’s hot fantasies and the banal mentality of the real child, who’d rather be (and should be) eating a hot-fudge sundae. Nabokov’s Lolita,unlike Lyne’s, is not the story of a May-December romance. His portrait of Humbert, my therapist friends tell me, is a chillingly accurate depiction both of the solipsism of the child abuser and the pathos of the abused child.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that Adrian Lyne, Geiger counter of the sexual Zeitgeist, has created such a sexually knowing, at times predatory, Lolita. It’s fashionable today to be disdainful of the language of “child abuse,” and to trumpet -- as Katie Roiphe does in a memoir of her own affair, when she was 16, with her 36-year-old teacher -- the “power” that younger women hold over their older lovers. But this is actually an old, old story, revived by Roiphe and other members of the “sex as female weaponry” school of feminism.

Using a 14-year-old actress in graphic sex scenes may cross the line with censors (hence, the love scenes have far less skin than we are used to), but images of seductive female temptresses -- of all ages -- have an ancient and enduring lineage in our culture. After all, it wasn’t so long ago that some lawyers were still defending child molesters on the grounds that the little girls had seduced them.

Far harder for us to digest are images that do not erase the difference in power between adult and child. Recall, in 1995, when Calvin Klein was forced, submitting to public protest, to yank a series of CK perfume ads from television and magazines. In these ads, the waif-like bodies of young boys and girls were arranged awkwardly, underwear exposed, as though they weren’t posing for a picture, but caught unawares. In the television version of the ads, the voice of the adult photographer could be heard telling the child to take off her jacket, turn this way or that, while she performed for him guilelessly, awkwardly. People were unnerved by the presence of the adult, intruding into the world of the child, manipulating and arranging her body -- exposing her -- while she remained apparently oblivious.

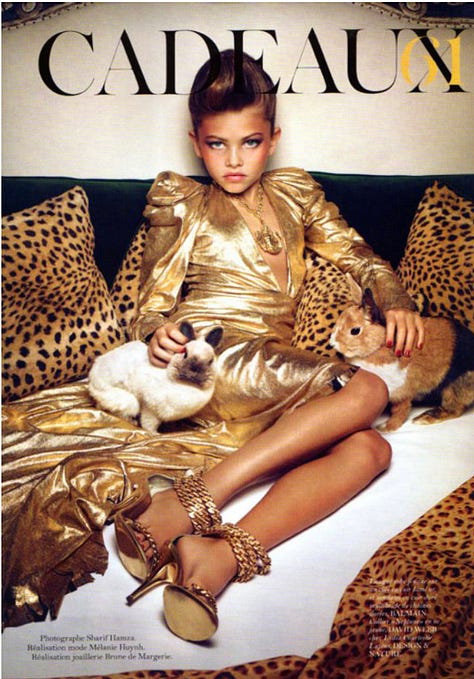

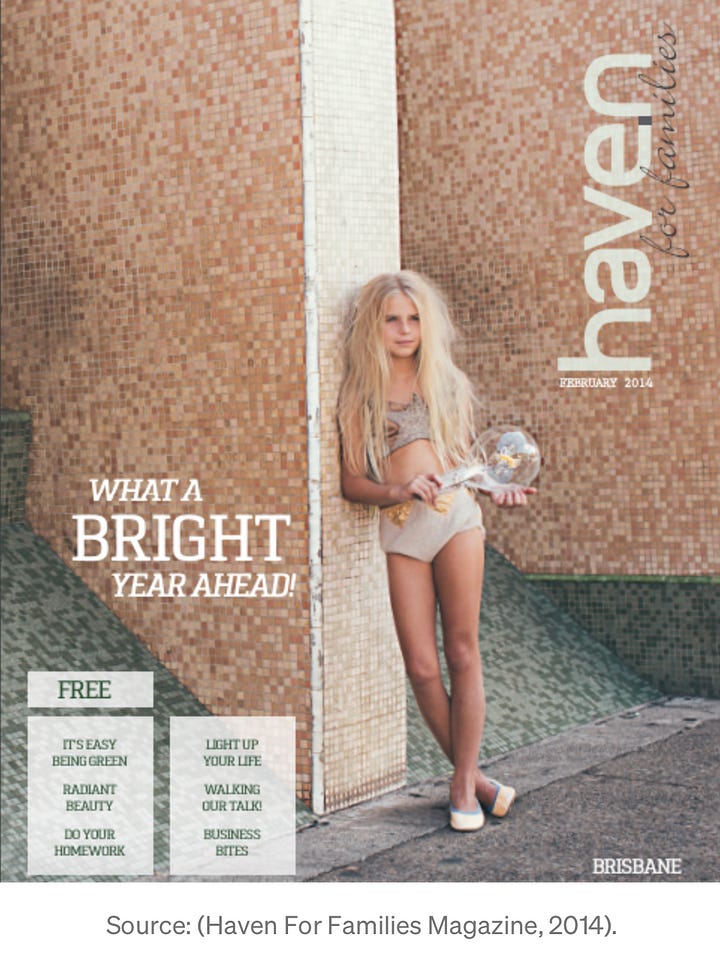

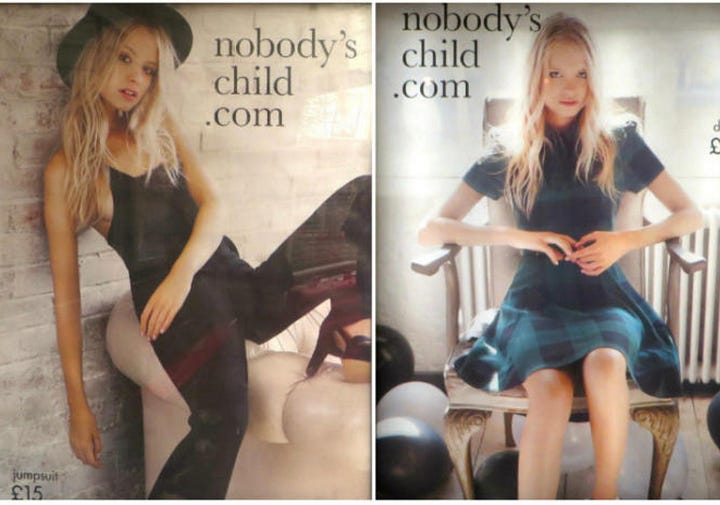

Some people, perhaps, were titillated by these ads despite themselves. The unconfronted secret of our culture is surely not childhood sexuality (didn’t Freud take care of that one?) but the adult eroticization of children (the secret he may have covered up). Today, soul-shattering charmers are all over the fashion pages. The models themselves may not be minors (as the fashion designers retort to those who claim they are marketing soft-core kiddie porn). But many of the images could be illustrations for a coffee-table edition of Lolita. Why are these ads okay, while Klein’s were not? Because in these ads -- unlike Klein’s and unlike Nabokov’s Lolita -- the adult’s lascivious, intrusive gaze is obscured rather than acknowledged. We thus don’t have to confront the fact that we have become a culture of soft-core Humberts.

What Nabokov could not foresee, before the empire of mass images had colonized our imaginations, was that the undeveloped female body that he presented as emblematic of the nymphet would become a dangerous obsession for young girls, too. Many young girls today are as disgusted as Humbert by the spectacle of their bodies plumping out into womanhood, are as disturbed by their own hungers and desires (for sex, for comfort, for food) as Humbert was of the adult woman’s needs. They find the skinny bodies of the models compelling for the same casual, desireless sex appeal that Humbert found entrancing in Lolita.

As one of my students said about Kate Moss: “She looks so cool. Not so needy, like me.” This student had been struggling with bulimia all semester, and had a history of sexual abuse. She was an ex-Lolita trying to find salvation -- paradoxically but also logically -- by becoming the diffident waif that our cultural imagery has endowed with not only sexual appeal, but also immunity from hurt.

Unlike Nabokov, we are not inclined to tunnel deep into the content and meaning of the images that obsess us, whether as sexual fantasies or as blueprints for girls’ bodies (and souls). Instead, we focus on the ethics of the images’ production -- the age of the actresses and models employed, whether they have been made to diet for their jobs, and so on.

Taken to task for their role in promoting eating disorders, designers scoff and claim that the look is “just fashion,” pointing out -- often lying to us -- that the models eat like horses. The parents of children who participate in kiddie beauty pageants think they’ve covered themselves ethically if their little girls claim to enjoy the pageants (while seductive photos of JonBenet Ramsey continue to be plastered everywhere, even by commentators -- like Geraldo Rivera -- who have declared them “obscene”). Adrian Lyne boasts to Premiere magazine about how well he protected Dominique Swain, by putting a pillow between her body and Jeremy Irons’s; then he turns to the interviewer, his face alight with excitement over the scene: “It’s sexy, isn’t it?”

Well, it is sexy. But when was sexual titillation ever the point of Lolita? True, Nabokov was not a moralist: At many points in the novel, we are encouraged to empathize with, identify with Humbert. But, at the same time, we are called on to look squarely, clearly, consciously at his created dream world and its disjunction from reality. Therein lies the morality of Nabokov’s Lolita, and the mistake of Lyne’s. His movie -- once again a barometer of the cultural Zeitgeist-- hasn’t awoken from Humbert’s dream.

Excellent article. I see "Lolita" a little differently. Nabokov wanted his books to be made into movies, and as if courting this goal, there are a good 30+ pages of "filler" in Lolita that don't belong there, imo, and, notwithstanding Nabokov's ambitions, this story cannot properly/legally/ethically be made into a movie. I'd like also to note that the main character in this book, as in many fiction stories, is the narrative voice. Nobody could out "voice" Nabokov. So, here is a "pedo" who is smarter, better read, better educated, cleverer, etc, than the "dear reader", who might be apt to condemn Humbert in a huff of moral superiority. Pale Fire perhaps takes this voice aspect of voice even further.

There is no substitute for the book!. Although he Kubrick version ia pretty good with HH, Calre Quilty, and the elder Haze.