To my subscribers and friends:

Thank you!

When I started BordoLines a year ago, I was a wreck.

I had been looking forward to retirement, but instead got whacked with a nervous breakdown, the unexpected death of a beloved sister, a back that decided to mount a wicked protest against my decades of sitting and writing, and—along with everyone else—the pandemic. The fantasy I’d had—that some mainstream media outlet would grab me for a weekly column—was not only not coming true, but a new, younger generation of feminist mavens seemed to have taken over. And, for some still unknown reason, my agent, after many successful years working with me, disappeared on me. I mean really disappeared. Didn’t answer emails, didn’t answer phone messages. Disappeared.

I don’t know what gave me the idea to start a substack “space” (what I do isn’t really a newsletter) but it had something to do with a new stage of grief over my sister. I could call it a stage of “recovery”—except that’s a myth, isn’t it? We don’t recover from some losses; we just learn to live in the unfamiliar, diminished world of the “after.”

For a long time I couldn’t write, not just because apparently no one was clamoring for my words, but because I needed not to lose myself in my writing. It felt wrong—not as a betrayal (I knew my sister would want me to keep writing) but viscerally. My mind still swarmed with ideas. But my body simply would not sit down at the desk and put words to them.

For a long time, I fought it. I struggled through the final stages of a little book on television that I’d signed a contract for. I tried to write some pieces for “Medium.” But I came to realize that my body, slowed down and reluctant to “move on,” was wiser than my always bubbling-with-stuff mind. It knew it was necessary for me to integrate the changed world—the “after” world—into the ideas and feelings that I give expression to when I write.

At some stage, that happened. And substack was there. In one of my first pieces, I wrote about the change this represented in my writing life (If the script below is too hard to read, you can read it here:)

At first, I was compulsive about it. “I need a schedule,” I thought, and planned to do two posts a week, one on politics/media criticism and one on movies/television. And for a while I kept that up, somewhat frantically. Used to working on contract and with editors, I had to remind myself that there was no real deadline except what I imposed on myself. And I had to exorcise myself of the absurd (and absurdly self-important) idea that if I didn’t produce what I’d promised my subscribers “on time,” they’d abandon me.

What slowed me down, eventually, to every 5-7 days was remembering that this was supposed to give me pleasure, not create a new version of the stress that I’d felt all my life, trying to be a writer and a teacher at the same time. I loved both, but as many of you who are living that kind of life know, it’s exhausting. And for me—not for every writer—one of the things that gives me huge pleasure is the incubation period, when doing “research” for my pieces would bring the insights and connections to the surface. I loved days spent reading interviews with directors and culling quotes from screenplays. I loved seeing the same show or movie over and over, as many as necessary until I felt that when I’d sit down to write it would all be “there,” ready for me. Sometimes I’d be pulled into genres of shows—which amounted to a multi-day film festival. And for every political analysis or piece of media criticism, there were transcripts, broadcast and print “texts” to dive deep into.

For me, all this isn’t subordinating writing to “research.” For me, it’s by being precise about what we think that we avoid in our writing what Orwell called “surrendering to words”—that is: “throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you — even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent — and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.”

What we should be doing instead, according to Orwell, is “let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around.” But to do that, you need to figure out what you mean to say—not what others expect you to say, or what’s easy to say. And that—at least if you’re doing the kind of writing I do (I recognize that certain kinds of creative writing are different)—is what research gives you: the clicks, the sparks, the unexpected links that lead you to what you need, what you mean, what you have to say. And that’s always thrilling.

Substack gave that back to me. What I didn’t expect, though, was that I’d find a community as well. And over the past twelve months, that has become as important to me as the writing itself. The conversations! The generous, attentiveness! The encouragement and warmth. The empathy. So much intelligence. Such inspiring writing. The emerging possibilities for working together with others! I truly didn’t expect any of that; I was just looking for a way to keep going as a writer. And you’ve given me so much more. (I would list names, but I know from past experience that you can get into trouble doing that. You all know who you are.) Thank you.

If you’re a new subscriber, welcome!! I hope you’ll treat BordoLines as a place for conversation. You’re going to “meet” some wonderful people here. And if you’re so inclined, browse through the past year’s posts and let me know what you’d like to see more of. (There are categories on the home page.) And thanks again!

Hugs, Susan.

All dolled up for “Barbie” party:

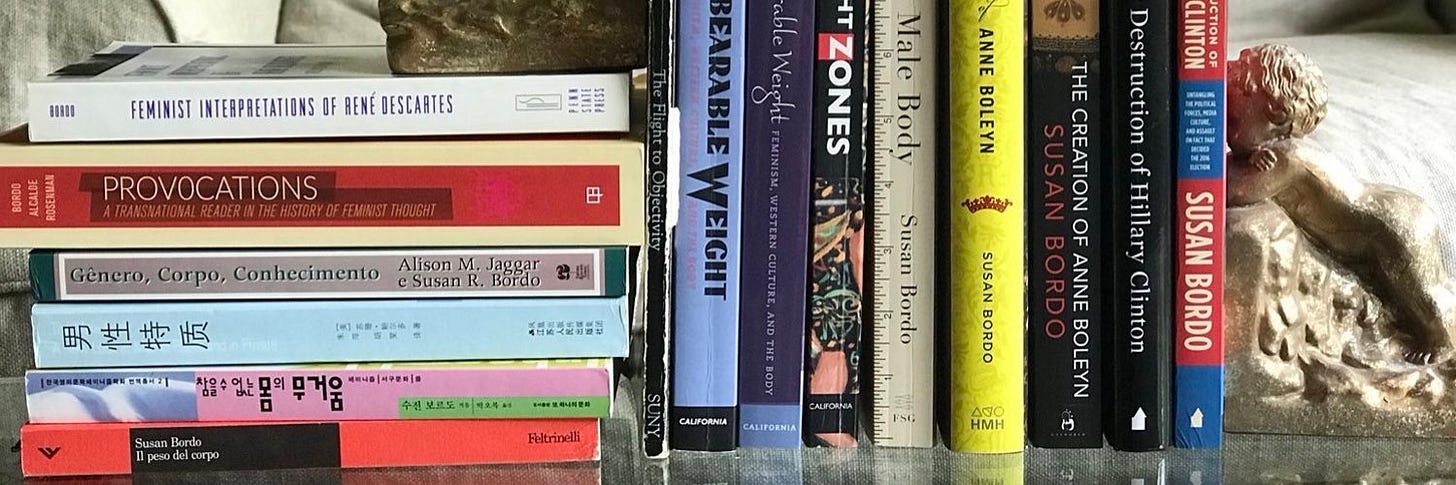

(If you’re interested in learning more about my books, see my website: Bordocrossings.)

Congratulations on your second year! I'm so glad you're here--and gladder still that I found you! ❤️

Susan! Thank you for lighting the way despite a plague of troubles. You were my first Substack mentor. We never know what our mentors carry.