Where the Girls Aren’t (Sort of a Review of “Brats”)

They aren’t mentioned in the article that sent Andrew McCarthy into an existential crisis. But they are what’s most memorable about 1980’s youth movies.

On June 10, 1985 a snide, haphazardly written article by a 29-year-old contract journalist hoping to make his mark as a witty pop chronicler threw 22-year-old actor Andrew McCarthy into an existential crisis from which, by his own admission in his documentary “Brats,” he never recovered. “My recollection,” he tells David Blum, author of the New York magazine piece, “is that it was instantaneous, and burned deep, and…I just remember seeing that cover and being like, “What just happened?’ Really, it hit like that-like a car wreck. And I felt instantly—and it proved to be the experience—that I’d lost control of the narrative of my career.”

Although McCarthy’s entire documentary is devoted to it, the nature of the “car wreck” is never quite made clear. Was it being branded a “brat”? Being lumped together as a group of “young movie stars you can’t quite keep straight?” Was it not being taken seriously enough as an actor? Was it the fact (never noted in the documentary) that McCarthy himself is barely mentioned in the article? Whatever, it’s haunted McCarthy for nearly four decades and he goes on a healing journey to interview a bunch of those he regards as other members of the pack. None of them seem as traumatized as McCarthy, but they humor him, and discourse on the watershed nature of that historical moment when Hollywood, apparently, discovered the teen movie-going consumer. “In the history of Hollywood it had never been like this,” says Rob Lowe, glowing with excitement. McCarthy is so earnest and dedicated to his quest that he even gets cultural maven Malcolm Gladwell to agree that the 80’s teen-and-twenty-something movies were a “tipping point.”

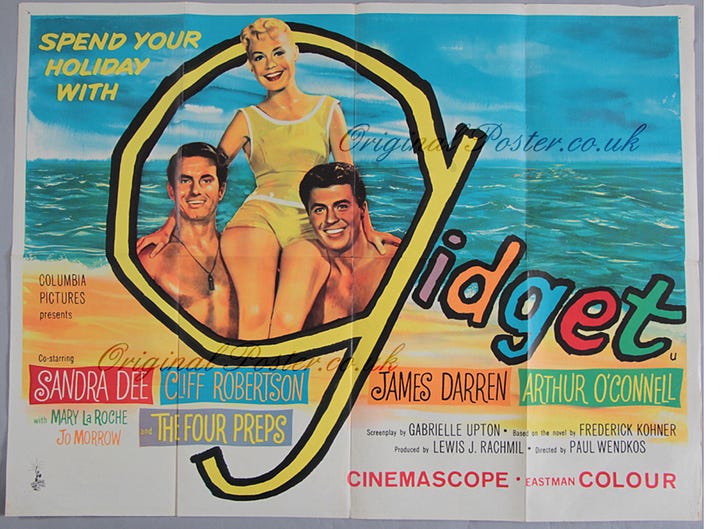

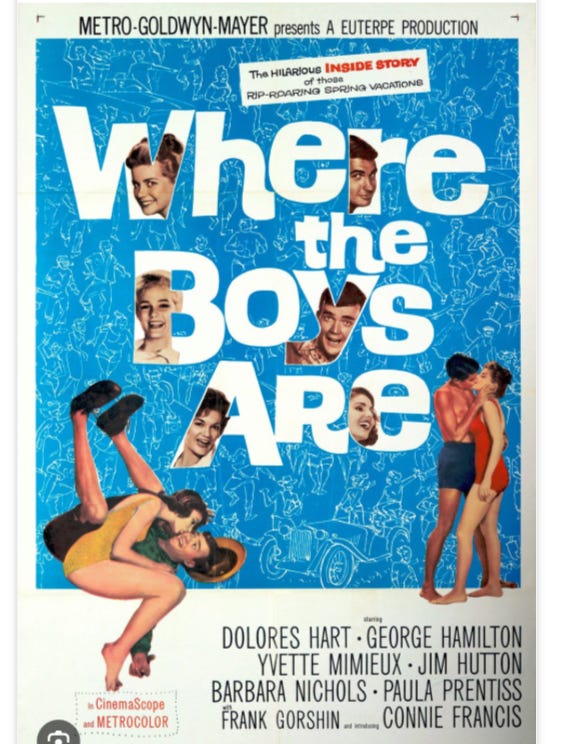

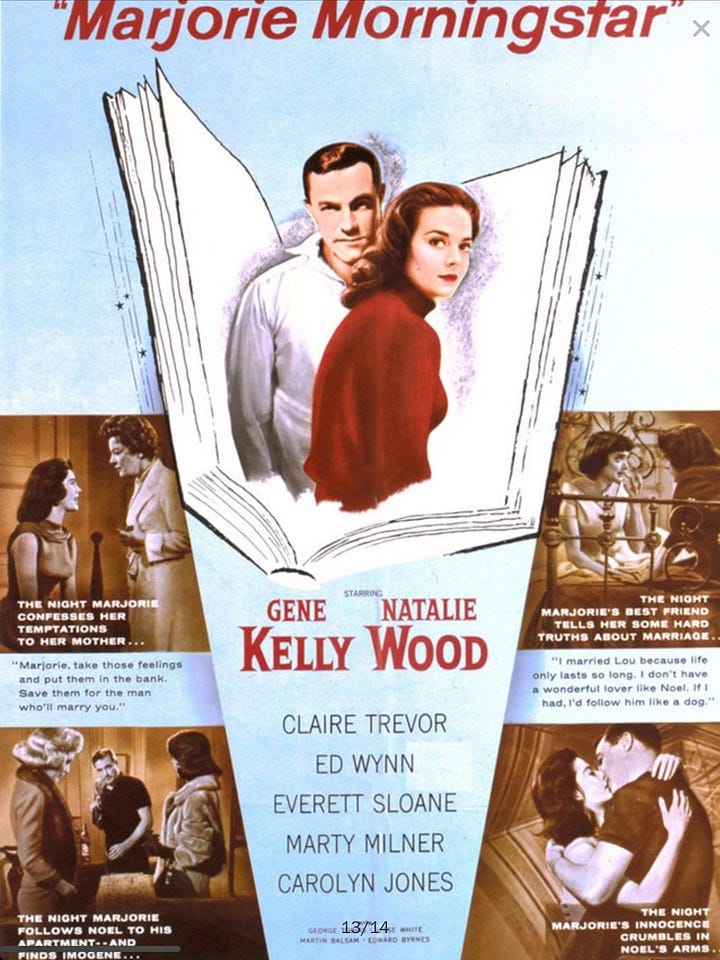

I don’t know. Until my mother threw them out (along—sigh—with the original copy of “Mad” magazine) my piles of “Photoplay,” “Screen Stories,” and “Movie World” from the late 1950’s—early 1960’s suggest my boomer generation had already “tipped” movie culture in the direction of the teen consumer. Do the names Frankie Avalon, Fabian, Sandra Dee, Sally Field, Connie Francis, Troy Donahue, Ed “Kookie” Byrnes, “Tammy” or “Gidget” mean anything to you? Don’t gag—there were also some very serious dramas, many of them dealing with the then-crucial decision of whether to “do it” or not, and what happens to girls that do: “A Summer Place,” “Where the Boys Are,” “Majorie Morningstar.”

My own fantasies can still be awakened into adolescent yearning by a clip of the young Warren Beatty in “Splendor in the Grass.”

I could go back even a little earlier, to the mid-50’s panic over “juvenile delinquents”—which gave us Marlon Brando (“The Wild One”) James Dean (“Rebel without a Cause”), Sal Mineo (same) and a gorgeous young Sidney Poitier (“Blackboard Jungle”) But “Brats“ isn’t about the origins of youth consumer culture. That’s just McCarthy et al turning their personal nostalgia (or disappointment) into a major cultural moment. Which I suppose it was, for a later generation than mine.

Despite McCarthy’s leading probing (he refers to the “New York” article in terms like “triggering,” “stigma,” “branded,” “reprehensible” throughout his questions) it’s pretty clear that all of them aren’t equally haunted by their youthful glory or the day the music stopped. Emilio Estevez, unlike McCarthy, is “not interested in, you know, dredging up the past because I think if you’re too busy looking in your rearview mirror and looking at what’s behind you, you’re going to stumble trying to move forward.” Rob Lowe, whose chiseled face is still as shiny and smiley as ever, is happily philosophical about the temporary nature of “that moment” and Demi Moore, warmly dispensing a lot of of psychobabble, actually seems kind of at peace. (McCarthy, determined to project his own crisis onto the entire pack, doesn’t note that Demi’s career went skyward in a way that the others’ did not. Her house is huge. She’s famous, dude.) Ally Sheedy is lovely and patient with Andrew’s morose musings, but her memories are much happier than his. For her, as for Demi, she’s grateful for the chance she was given to play a character (as Jules in “St. Elmo’s Fire”; for Ally it was Allison in “The Breakfast Club”) that she identified with. “There’s a lot of me in Allison,” Ally says, “the feelings, and the fears and things that she’s going through, I know that they were coming right straight from me.” Demi, while filming St. Elmo, had to have a coach with her monitoring her drinking.

Puzzled and irritated by McCarthy’s kvetching, I decided I should read the original article—and was amazed to find the he wasn’t even mentioned in it until near the end, when he is referred to merely as “one of the New York–based actors in St. Elmo’s Fire,” and quotes a co-star as saying, of McCarthy, “He isn’t going to make it.” No wonder he’s so pissed off. The piece is basically an account of a night Blum spent carousing at bars with Judd Nelson, Emilio Estevez, and Rob Lowe, high on new-found fame and the attention of girls (not exactly a context in which to talk seriously about acting, the movies, or the meaning of life.) It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that McCarthy was more insulted at being left out of the glamorous group than being branded as one of the “brats.”

It’s not just McCarthy, though, who isn’t granted admission to the club. None of the girls who starred in the movies associated with Hughes’ movies and/or the youth-wave of the 1980’s—Ally Sheedy, Demi Moore, Molly Ringwald—made it into the article either. What? No Molly Ringwald? John Hughes’s muse? The girl who—bless her—brought red hair back in style? Nope. The Brat Pack, it turns out—at least as it existed in the mind of David Blum—is an exclusively male frat. Here’s the rest of the group as described by Blum:

The Hottest of Them All—Tom Cruise, 23.

The Most Beautiful Face—Rob Lowe, 21.

The Overrated One—Judd Nelson, 25.

The Only One With an Oscar—Timothy Hutton, 24.

The One Least Likely to Replace Marlon Brando—Matt Dillon, 21.

The Ethnic Chair—Nicolas Cage, 21.

The Most Gifted of Them All—Sean Penn, 24.

Not Quite There: the Two Matthews—Broderick, 23, and Modine, 24.

I agree with Blum’s assessment of Sean Penn. But where are the girls? Not bratty enough? Didn’t happen to show up at the bar that night? The irony of Blum’s excluding Ally and Molly (Demi was only in one of those movies, so her absence can be excused) is that it’s arguably their characters that have made the most lasting impression on viewers. (That would mostly be female viewers, so I guess not as definitive of “the culture” and where it was “tipping” than Emilio, Rob, and Judd.)

Blum’s article aside, eventually, the girls did get included in homages to the movies of that era. I asked my Facebook friends which of “Sixteen Candles,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Pretty in Pink” and “St. Elmo’s Fire” was their favorite and pretty consistently, it was “Breakfast Club” (1985) and “Pretty in Pink” (1986) —with special notice given to Ally Sheedy’s withdrawn, quirky pre-Goth Allison, all in black, hair in her eyes (“The Breakfast Club”) and Molly Ringwald’s working-class Andie (“Pretty in Pink”) with whom they most identified. The outsiders, the non-belongers, patching together their own style out of what little is available to them, not the preppies of “St. Elmo’s Fire.” One comment:

“My favorite at the time was Pretty in Pink. I was 17 and a high school senior when it came out in early 1986, so I was definitely the target audience and the age of the characters. Pretty in Pink especially spoke to me because of the class issues - I really identified with the Molly Ringwald character being poorer or working class & liking the popular rich boy, but also her loyal friend group & musical tastes being quirky & important to her. Hughes really captured that economic class angst & divide at that time. For the characters caught in the narrow social world of high school it seemed like an impassable & permanent obstacle.”

These yearning girls, in the two films in which “insider/outsider” defined the teenage experience (that, and being misunderstood/abused by adults—the principle in “The Breakfast Club” would surely lose his job today) had the most near-universal appeal, in part because in Hughe’s all-white world, “working class” was as close as you could come to the real-world divisions that the films largely ignored. So, McCarthy’s one Black interviewee—pop culture critic Ira Madison III—was able to “empathize and connect with” the outsider characters in “Pretty in Pink” and “The Breakfast Club.” And Molly Ringwald, in 2018, recalls how a gay, Black “friend of a friend” told her that “The Breakfast Club” saved his life by showing him “that there were other people like me who were struggling with their identities, feeling out of place in the social constructs of high school, and dealing with the challenges of family ideals and pressures….finding themselves and being ‘other’ in a very traditional, white, heteronormative environment.”

We’d need to do a broader survey to find out just how common such a sense of connection with the movie was. I’d also like to know how young girls, in 2024, would react to the scene in “The Breakfast Club” in which Bender [Judd Nelson], hiding under the table where Claire [Molly Ringwald] is sitting, does something (we don’t know what, but it makes Claire gasp.) The viewer is also given a shot of what Bender sees under there: Claire’s slightly spread legs, exposing her panties. It didn’t bother Ringwald (or most viewers, including me) at the time, but in 2018, watching “The Breakfast Club” with her daughter, she was surprised and disturbed at how “Bender sexually harasses Claire throughout the film. When he’s not sexualizing her, he takes out his rage on her with vicious contempt, calling her “pathetic,” mocking her as “Queenie.”… He never apologizes for any of it, but, nevertheless, he gets the girl in the end.”

In 1985 the terms Ringwald uses—“sexual harassment,” “sexualizing”—would have brought a scornful (or perhaps uncomprehending) “wah?”from most viewers, male and female. But Ringwald still puzzles over how Hughes, so attuned and sensitive in so many respects, could have included the episode in “Sixteen Candles” (1984) in which “dreamboat, Jake, essentially trades his drunk girlfriend, Caroline, to the Geek…who. takes Polaroids with [an unconscious] Caroline to have proof of his conquest; when she wakes up in the morning with someone she doesn’t know, he asks her if she “enjoyed it.”…Caroline shakes her head in wonderment and says, “You know, I have this weird feeling I did.”

Jokes about sex with unconscious women probably wouldn’t play as well in 2024.

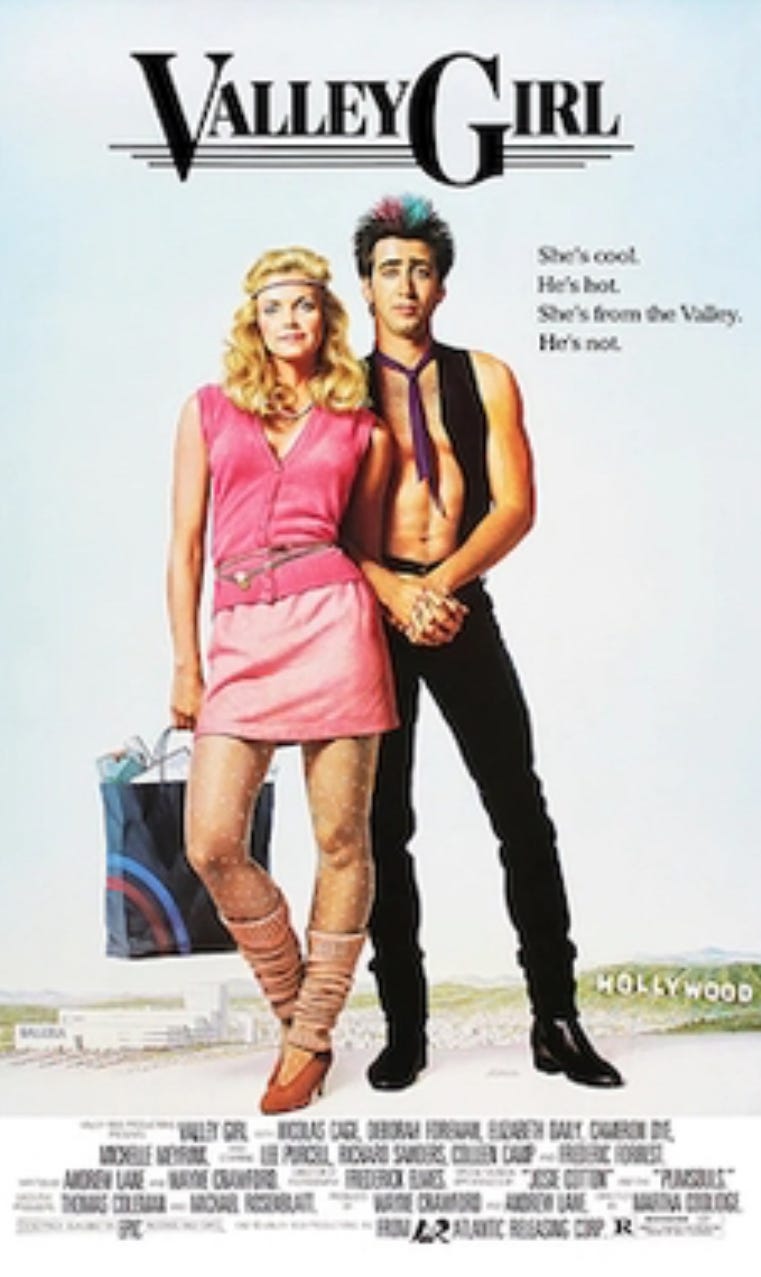

Despite that, Ringwald—to whom I will always be grateful for the hair thing—credits Hughes as the first Hollywood director to make movies “about the minutiae of high school…from a female point of view.” But that’s not exactly correct, and not just because it’s the male gaze peeking at Claire’s panties. There’s Martha Coolidge’s quirky “Valley Girl” (1983) and Cameron Crowe/Amy Heckerling’s “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (1982), both girl-centered movies—a genre that somehow always gets shoved to the margins, never gets to constitute a “tipping point.” (Simone deBeauvoir had something to say about that.)

Amy Heckerling, a first-time director who later went on to make “Clueless” (imo, the best screen adaptation of Jane Austen’s “Emma”) was less self-consciously focused than Hughes was on major teen “issues” (e.g. with parents and teachers, cliques, labeling and bullying) than on the everyday culture of teen life, and she deliberately chose a cast that still had baby-faces and had them behaving cluelessly in virtually every situation. The movie is funnier, sweeter, and, especially if you’re a teenage girl, more “like real life” than any of the Hughes movies. Everyone (not just those from the “wrong side of the tracks”) works after school. At the mall. Stacey (Jennifer Jason-Leigh, so adorable) decides to lose her virginity pretty much the way I did—time to get it done with. She tries with a nice boy who runs scared, leaving her baffled. (Don’t all guys want to do it? What’s wrong with me?) Sex with the more “experienced” guy is split-seconds long and then he runs away too. It’s all so recognizably, miserably awkward. (The studio heads, disappointed, called the movie “sexual but not sexy”—which of course is what teen sex often is. Or at least, used to be before teenagers learned how to do it from the internet.) But one-time crappy sex is enough to get Stacey pregnant. She has an abortion—and yet (gasp!) manages to go on with her life.

And there’s even a few Black teenagers at their high school (Forest Whitaker’s first role)!

I feel compelled to end roundly, now that I’ve tried to put a few cracks in the iconic status of the “Brat Pack” boys, by returning to Andrew McCarthy’s documentary.

Near the end of “Brats” Andrew McCarthy interviews David Blum, who does turn out to be a self-satisfied, unapologetic jerk. When pressed by McCarthy, his response is basically “what’s the big deal?” (I was a journalist, it was a good story, I did my job. And hey, by the way, I should get some credit for making you all household names, don’t you think?) When McCarthy, near the end of their talk, asks “But do you think you could have been nicer?” I thought he was having a rare, jokey moment, poking at his own neediness. But no, he was being serious. It was so painful to “lose control of the narrative of [his] career” McCarthy says; couldn’t Blum (who McCarthy doesn’t seem to realize was more concerned with his own career) have been a little gentler about it? But Blum isn’t giving him anything: “I guess I feel like, you know, sticks and stones.” He’s an ass, but he has a point.

If you haven’t seen it, watch “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”

Yes a little sad McCarthy positioning himself as resenting the group’s label whilst reviving his membership of the group.

I remember that original “brat pack” article and thought it was both silly and sexist at the time - no Molly Ringwald or Ally Sheedy?! You nailed it here, Susan, and I love your take on poor, morose Andrew McCarthy - you’ve also convinced me to watch “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” again, long a favorite 😉