Anora, Anora, Anora!!

For me, It was a moment of pure delight when Anora swept the Oscars last night. I’ll tell you why, but WARNING: Contains “spoilers”

Sean Baker’s “Anora” invites our capacities for feelings, not judgment, to accompany one young, female sex worker through a few roller-coaster, genre-defying weeks in her life. Like all of Sean Baker’s films, it refuses an ending that tells us what to think. It doesn’t tie things up and lead us to a morally unambiguous conclusion but to the perfect, emotionally right one. And the magic of it is that it does it without much being said. While the comic parts of the movie, like classic screwball comedies, are full of characters whose talk bumps into each other, jostling for our attention and laughter, the last movement has hardly any dialogue at all. And it will stay with you for a long time.

Last night, this “small,” independent film swept the Oscars, winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Editing, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress, and I’m sure that you’ll be reading and hearing lots about it.

It’s been disappointing to see that my two stacks on “Anora” have gotten far, far less attention than my movie stacks have in the past. Perhaps the horrifying political events of the week are partly responsible for that. I know they made it hard for me to write about movies—even this movie that I’ve loved from first viewing. But I also suspect that many of you hadn’t seen the movie yet. (A movie editor friend of mine said, before the Oscars, that if it won Best Picture it would be the lowest-grossing picture in Oscar history to do so.) I hope that will change now that the Oscars have celebrated it in the way I’d hardly dared to hope. I’m pretty cynical (or call it realistic) about the Oscars and how and why they reward what they reward.

Let me share with you, this time in one condensed stack, some of the writing I’ve done on this film. Including my interpretation of that ending.

1. Sean Baker Deconstructs the Rom Com

It makes for some good review headlines:

“Sean Baker’s ‘Pretty woman’ is a triumph,” “Mikey Madison’s Modern-Day Take on Pretty Woman is Dazzling,” “Mikey Madison Blazes in this very modern Pretty Woman tale,” etc.

But writer/director Sean Baker wasn’t inspired by “Pretty Woman”—at least not consciously:

In September Baker told IndieWire : “Honestly, I didn’t even pick up on that until halfway through production and somebody called it out and I was like, ‘Oh, okay. Yeah, I see that.’ But I didn’t want it in any way to affect me. I didn’t want to be influenced by it. So I decided to not revisit it and to tell you the truth, I still haven’t revisited it, so I haven’t seen it since 1990.”

If you’re familiar with Baker’s films “Tangerine” and “The Florida Project,” you’ll find a much clearer line from his own earlier work to “Anora” than from “Pretty Woman” to “Anora.” The central characters of “Tangerine” are two transgender sex workers: Sin-Dee (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez) is prowling the streets of West LA looking for her cheating boyfriend while her friend Alexandra (Mya Taylor) is picking up a little money while distributing flyers for her appearance that night at a local bar (she sings “Toyland”—and made me cry.) “The Florida Project” follows the adventures of Moonee (Brooklyn Prince), an imaginative, streetwise six-year-old whose laissez-faire mother Halley (Bria Vinaite), improvising ways to make her rent money, steals and sells tickets to Disneyland and has sex with men in her motel room. Both films, like “Anora,” are no-limits raunchy, funny, warm, and have segments of everyone-talking-loud-at-once chaos and physical slapstick, then unexpected turns that will haunt you forever. Running through the psyche of all three films are fantasy-worlds imagined as escapes from the hierarchical, crushing realities of hardluck adult life “on the margins.”

So: Sean Baker didn’t wake up one day thinking “Hey, what about a film about a sex worker with fairy-tale dreams!” But Baker, who was 19 when “Pretty Woman” was released and a movie buff from an early age, didn’t have to have seen it again for it to be stored somewhere in his memories. The film, and particularly its breakout star Julia Roberts, became (much to the surprise of the cast and director Garry Marshall) both a film and cultural sensation. Audiences were dazzled by Roberts’ mega-watt smile and natural instinct for seemingly unselfconscious charm. The chemistry between her and Richard Gere was right. And in the 1980’s and early 90’s, Hollywood often tried to incorporate some version of feminism—often by featuring working women struggling with classism, sexism, and (less frequently until we were well into the 90’s) racism—into traditionally entertaining formats.

You might be thinking: Feminist? “Pretty Woman”?? And for sure, there’s a lot that’s cringe-worthy in 2025.1 But whatever we think in 2025 the question of how to inject a little feminism into the fairy-tale plot was a subject of concern among the makers of the film. Most notably, Laura Ziskin, the executive producer of the film, wanted the knight-on-horseback finale to end on a note of “equality”—and suggested a line to take care of it:

It’s not untrue to the plot, in which Vivian’s warmth and spontaneity does “rescue” Edward from his life as a work-obsessed head of a company that buys floundering businesses and sells them for parts. But face it, in 2025, it does feel tacked on to make the schmaltzy but entertaining scene more politically correct. The deliberateness seems borne out by the insistence by various members of the creative team (in a 2020 documentary on the movie): “She’s the one making decisions now,” “She’s evolved,” “It’s princess culture coming together with feminist culture.”

Hmmm. Maybe a tad more princess culture than feminist culture. (Or maybe more precisely Julia Roberts culture; every woman wanted her tousled hairstyle, long legs, and gorgeous outfits in the film.)

But interestingly, the original screenplay didn’t even have a happy fairy tale ending in need of feminist tweaking. In the original version, written by J.F. Lawson, “The idea was to draw a parallel between Edward’s greed and Vivian’s complicated and disjointed life, which represented American society….[And in the original, called $3,000, the price for Vivian to spend the week with Edward] in the end, the businessman left the young woman on the pavement where they had met a few days earlier, throwing the promised cash out the window in exchange for her company. With the money, Vivian and her friend Kit went on a trip to Disneyland. 2The film ended tragically: on the way, Vivian, originally written as a drug addict, died of an overdose.”

Funding, unsurprisingly, was hard to get for this dark version. Then Disney bought the rights and Garry Marshall was appointed director. Marshall was noted mostly for his work on popular television sitcoms like “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” “The Odd Couple,” “Happy Days,” and “Laverne and Shirley.” The script went through several revisions, and “the quintessential romantic comedy couple gradually took shape.”3

So: When Peter Debruge, in Vanity Fair, describes “Anora” as “a subversively romantic, free-wheeling sex farce [that] makes ‘Pretty Woman’ look like a Disney movie,” it’s truer than he seems to be aware. “Pretty Woman” is—literally, not just metaphorically—a Disney movie. “Anora” is neither. In fact, you could say that “Anora” is a deconstruction—not an update—of “Pretty Woman,” which returns us to Lawson’s original intention to draw a contrast between the cold obliviousness of the privileged and those who scramble to survive in the world that the Edwards (whether American or Russian)—not the Vivians and Anoras—own.

Insofar as it’s a comedy, “Anora” is a screwball comedy

Rom Coms like “Pretty Woman” follow the formula of classic (e.g. Shakespearean) comedies: There’s a first “act” of falling love, a second act in which misunderstandings, mistaken identities, personality or class differences, the interference of others, etc lead to obstacles to the relationship(s) and a lot of comic chaos. And a third act in which all obstacles are overcome and love (and usually, marriage) wins the day.

The classical comedy/Rom Com are thus celebrations of forever-after love and marriage. The screwball comedy, on the other hand, satirizes, spoofs and in various ways “screws with” that ideal.4And often, they feature feisty, feminist, female leads.

So, for example, in a screwball comedy like Preston Sturges’ 1941 The Lady Eve, the female protagonist Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) is a confident, bold, and manipulative con artist while the rich man she ensnares, Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), although from a superior class, is bewitched, bewildered, and bumbling (many pratfalls for Fonda.) And although Jean genuinely falls for him, she never loses her edge over him, in knowledge or world-wisdom. In a sexually scandalous ending (it remains suggestive only, to avoid the Hayes Office), the two nuzzle and declare their love for each other, even though he still thinks that he’s already married to another woman. Jean, however, knows that “other woman” is, in reality, herself, disguised as “Eve.”

A more contemporary take on the screwball comedy, P.J. Hogan’s 1997 “My Best Friend’s Wedding” has a rambunctious and super-confident (“she’s toast”) Jules (Julia Roberts) scheming in every way imaginable to recapture the love of ex-boyfriend Michael (Dermot Mulroney) from sweet and submissive Kimmy (Cameron Diaz, another actress with a mega-watt smile.) She’s not successful. The movie ends with a wedding, but it’s Michael and Kimmy’s, and Jules is dejected, sitting alone, toying with her cake. But there’s compensation: her “sleek, stylish, and radiant with charisma” editor George (Rupert Everett) shows up at the wedding, pulls her to him, and leads her to the dance floor, where he dips and twirls her. George is gay (and at his gorgeous prime in this movie.) So the heroine doesn’t get the ring and the man, but—as George tells her—“by God, there will be dancing!” It’s not just the ending, however, that screws with (in this case, queers) conventions of happily-ever-after heterosexual relations. Hogan pokes at them throughout the movie.

2. It may be a comedy, but “Anora” is a comedy that’s hyper-aware of the realities of power and hierarchy. And those realities deny a conventional happy ending.

The screwball comedy celebrates the woman who sets her sights on the man, won’t give up, but never, ever gives herself—her personality, her fighting spirit, her wit, her independence—up either. Anora is, indeed (and unlike Julia Roberts’ Vivian in “Pretty Woman”), as fierce and formidable as any of those heroines. But the ending of “Anora” shifts into a completely different register than that of screwball comedy.

I love the way literature professor and writer

put it in a response to my first stack on “Anora”:“I walked out of the theatre blown away because it felt like a film made in the 1970s, that magnificent era of cinema which allowed scenes to slow down, allowed audiences to grapple with ambiguity, and left us with a multi-faceted examination of character and critique of society. For me, the movie felt like a masterful baseball game which rounds the first base of Sean Baker’s compassionate realism, then hits the 2nd base of slapstick, passes third base’s move toward tragedy, and then slides gloriously home into the tender gravitas that so many ‘70s film depict.”

Beautifully put! Almost makes me feel as though I should stop right now.

But I won’t. Let me take you through it, including my interpretation of “the tender gravitas” of that ending.

Anora—or “Ani,” as she prefers to be called (Mikey Madison, who won the Best Actress Oscar, as well as several other earlier awards) is an expert lap dancer and sometimes more at a Manhattan strip club, where she meets and captivates Ivan/Vanya, the indulged but charming son (played by the “Russian Timothee Chalamet”, Mark Eydelshteyn) of a rich Russian oligarch. The owner of the club has taken her to him because she speaks Russian. In fact, she can but doesn’t like to (her unpolished accent? A desire to assimilate? Not clear.) A Brighton Beach native of at least part-Russian background (she had a grandmother who could only speak Russian) she understands everything when it’s spoken.

Unlike Vivian in “Pretty Woman,” Anora is no newcomer to the big city. She’s been at it for awhile, and is skilled and comfortable with the work.5 While Vivian’s country-bumpkin residue (which the script constantly emphasizes) reassured 1990 viewers that she’s “not really” a seasoned pro, Ani is unashamed and completely at home with her job. Sean Baker wants that from the viewer, too. As with “Tangerine” and “The Florida Project,” he neither judges, condescends, or exoticizes.

Vanya invites Ani to his family’s oceanside mansion, first for one night, then for a New Year’s Eve party, then for a week to be his “horny girlfriend.” (15K—some major inflation since “Pretty Woman” but a virtually identical bargaining scene) before he’s due to return to Russia and buckle down to work for his father’s business.

Here’s a clip in which Sean Baker describes how he shot Anora’s introduction to Ivan’s world:

Anora, while dazzled, remains composed and professional. It’s Vanya who is awkward and shy—in a kind of privileged way—as he skates barefoot across the (marble?) floor of the mansion and eagerly bounds up the stairs to the bedroom, where Vanya throws a comment about the maid’s negligence, then behaves with Ani like a hyperactive toddler with a great new toy. Sexually (and in other ways) he’s still an adolescent: always ready but not very adept (like a “spastic rabbit” as one reviewer put it.)

After Ani teaches him to slow down, Vanya becomes so smitten that he asks her to marry him (and—bonus!—he’ll also get a green card as the husband of an American.) At first she doesn’t believe him—she doesn’t expect marriage proposals—but he seems so guileless and endearingly, inarticulately enthusiastic that it doesn’t take that much to get her to agree. During the week they’ve spent together, he’s been a terrific (if wild and crazy) boyfriend, much more like someone who has found the girl he wants to go steady with than someone who has hired her to amuse him during his last trip to America. The proposal happens in a huge penthouse in Las Vegas, he insists that he is sincere (“I said it twicely”) and for that moment, it all seems to Ani like a fairy-tale in which anything is possible. (Maybe she’s seen “Pretty Woman,” too.) Vanya promises to get her a diamond ring with many carats and they’re off to say their vows.

It’s a whirlwind in Las Vegas, but after they return with a marriage certificate in hand, Ani begins to believe more seriously in her new status in life. She’s got the license, a dazzling ring, she’s a wife!

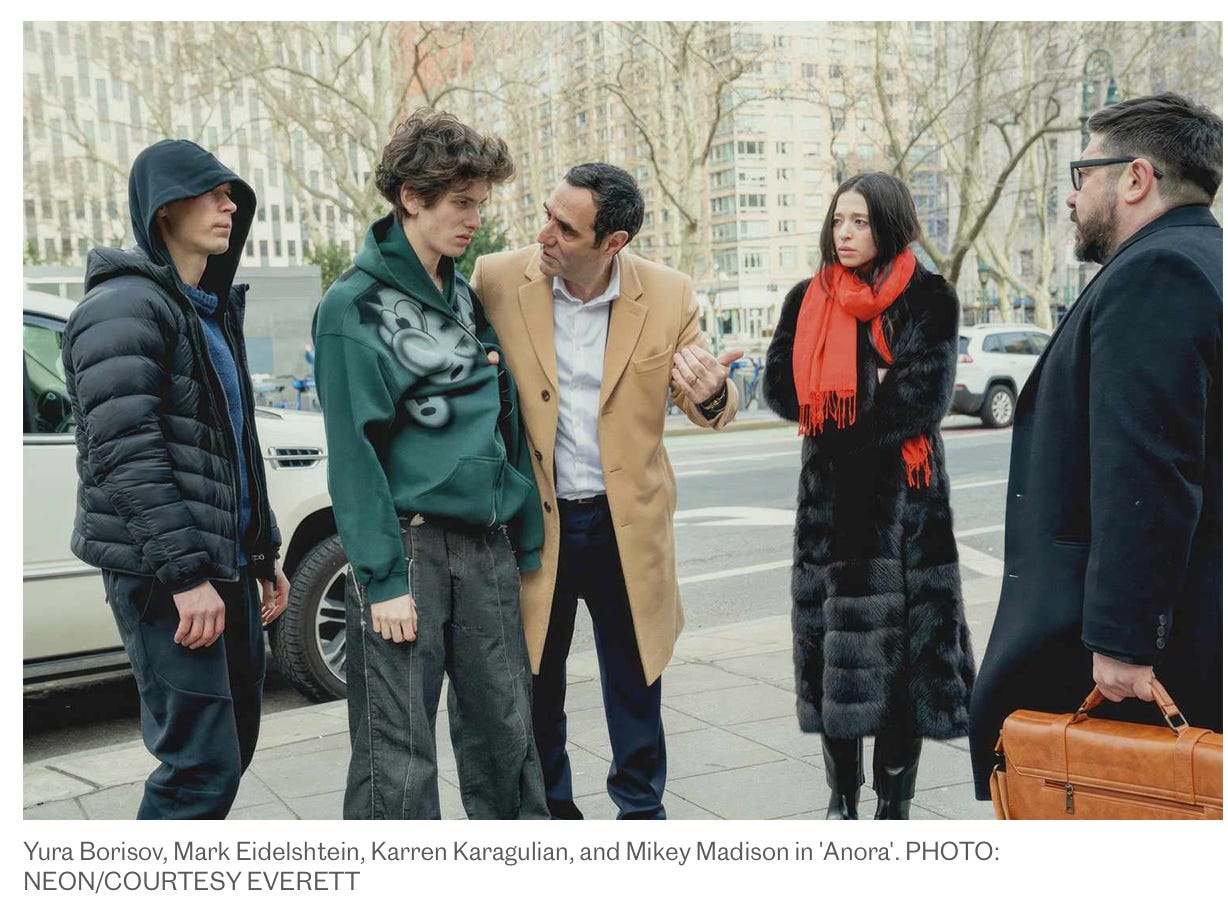

Harsh reality (and a transition to a different genre) crashes—hilariously for many viewers, not so much for others—into Ani’s possibility of an opulent life in the Zakharov’s mansion when word gets back to his rich, influential parents that their impulsive and frequently stoned son has gotten married. And—bozhe moy!—to a hooker! They dispatch Vanya’s Armenian godfather Toros (Karren Karagulian) who hands the baby over in the middle of conducting a baptism and speeds to the mansion after his brother Garnick (Vache Tovmasyan) and Russian “muscle” Igor (Yura Borisov, who was nominated but didn’t win Best Supporting Actor) let him know the rumors are true.

When Toros sends the parents a snap of the marriage certificate, they announce that they are coming to America themselves to fetch their wayward son, who they are used to rescuing from disaster, and get him an annulment. It’s at this moment that Ivan, hearing that his parents are on their way, stops being the prince in the fairytale and runs away like a guilty and scared little kid who’s caught with his hand in the cookie-jar. He doesn’t give a second thought to the fact that he’s left the cookie behind.

But this cookie is not so easily discarded. In the scenes that follow, Ani comes alive as a true screwball comedy heroine: ferocious and fighting for what she wants. (“Impressive!”says Igor, after she punches him in the face. She is—and so are the actors: Mikey and Yura did all the physical action themselves. No stunts—and many bruises.)

The fact that Ani “doesn’t fight like a little girl” and Garnick and Igor aren’t the brutal males that might be expected from henchmen (if this were a different sort of movie) is part of what makes the comic “home invasion” sequence fresh. No one wants to hurt her, just to keep her from running away (they need her to be present for the annulment.) But Ani, defiantly affronted and surprisingly strong, won’t be held down. Garnick’s nose is broken, the living room gets trashed, and Igor is forced to improvise ways to restrain Ani without hurting her. He’s huge, she’s 5 foot three, but she’s a match for him, partly because she’s so fearless, but also because Igor is so determined to keep her safe (something Ani can’t fathom, as the men she’s known at the club have other things than her protection on their minds.)

This is a section of the movie that some of my friends found jarring, gratuitous, excessive “mishegoss” (as one put it.) I guess you either find it funny or you don’t. I did. But the comedy aside, Sean Baker considered the 28-minute scene, which he arduously choreographed and later spent three months editing, to be essential:

“It was about getting them to that place where she was willing to go out with them to look for Ivan, whether or not they were on the same page.”

Cinematographer Drew Daniels adds that the scene takes us from “that feeling of exaltation, joy and happiness for [Ani] to: something is wrong and everything’s going to come to a halt.” In other words, the scene, while comic, is also a key transition into a new mode, deflating the fairy-tale that precedes it, as the beautiful wild pony that we’ve come to see is much more than an obliging sexual performer is subdued.

Subdued—but not broken. This is now a very different Ani from the customer-pleasing lap dancer we first saw at Headquarters. We’ve seen glimpses of her before, as she stands up to her boss or wrangles with Diamond, another dancer, but now she has something to really fight for, and the Brooklyn scrapper is called up. Fierce—but naively clinging to the legality of their marriage and Vanya’s affection. She’s convinced that once she gets the chance to talk to him, he’ll stand up for her and their marriage. And that hope persists, even after Toros has dragged them through all of Vanya’s Brighton Beach and Manhattan haunts and they’ve found him—in the club where he first met Anora—so inebriated that he can barely stand, much less defend Anora.

Ani isn’t about to give up, though, not even when the judge in Manhattan instructs them that they will have to go to Nevada for the annulment, not even when Vanya remains unresponsive, not even in anticipation of the arrival of the parents, In fact, Ani is sure they will see how in love she and Vanya are and bless the union. Igor watches it all and knowing the family well, thinks: Fat Chance.

When a regal, stony Galina (Daryl Ekamasova) descends from the plane, another female force of nature enters the picture. The guys don’t really have any power. Garnick is bumbling and vomiting and probably has a concussion; Toros lords it over everyone else but becomes a nervous supplicant when the parents arrive, and Vanya grabs onto his mommy’s waist and becomes the spoiled baby boy that he always had been. For him, the marriage was just a fun vacation. Igor carries the certain knowledge that Anora is about to be defeated by the heavy hand of money and status, and watches, silently. He says very little, but gradually, Baker invites us to imagine that there’s an inner life there that is different from the role he plays on the job—something that’s true of Anora too.

Touchingly (and amazingly, considering what she’s been through), Anora composes herself and deferentially approaches Galina with words about Vanya’s love for her and how delighted she is to be a part of the family. But far from warmly welcoming her, Galina coldly reminds her that she can ruin her if she wants—and Anora resigns herself to the annulment (although, good girl, she does get in a parting shot. “You are a disgusting hooker,” says Galina. Anora: “And your son hates you so much that he married one to piss you off.”)

3. That ending

“Anora” reminded me a bit of “The Bear”—not in the specifics (and “Anora” is highly specific)—but because both leave people who need to slot these things wondering. “What is this? Funny? Sad? Social commentary? Where do I put it?”

I recommend not trying to categorize it. Just go with it as it travels from the romantic fantasy of the first part through the manic, often slapstick, comedy of the second part, to the bursting of the fantasy in the next, and then, to “something completely truthful and unexpected” (as Greta Gerwig has described it.)

After the annulment, Igor is instructed to accompany Anora back home to Brighton Beach. Throughout, from the home invasion to the final moments of the film, Anora has been hurling insults at him which he, amazingly, doesn’t seem to have taken personally. It’s not because he’s a thick-headed thug, but because he seems to realize that she is in a generalized state of fury that’s justified by the treatment she’s gotten. All the subtle signs—nearly all wordless—that he’s not the “gopnick” Anora accuses him of are born out when he says, at the clerk’s office where they’ve gone for the annulment, that Ivan should apologize to Anora. Of course, Toros shuts that down, while Galina screams that her son doesn’t need to apologize to anyone. But it doesn’t come as a surprise to the viewer, and we realize that Igor the “muscle” has been the one who “sees”—the only one who “sees”—all along.

What does he see? In the world, the realities of power and privilege. And in Anora, a person of impressive spirit who has been insulted and treated like disposable trash by people who think they have every right to do so, yet still stands up for herself. A person who refuses to give any of them the satisfaction of knowing how hurt she feels. A person whose anger is the fuel that keeps her from being crushed. (Let her direct it at me, he thinks, I can take it and she needs to do it.) A person who on the plane back home, having been dragged around and bullied for two days, is finally able to close her eyes and sleep, despite the crying baby behind them.

This person needs to be warmed. He puts his coat over her.

That evening, they are sitting watching tv and smoking in the mansion. He’s relaxed and she is tense, easily irritated and prickly. There are moments when he says things that amuse her, but she can’t tolerate giving in to a real laugh. Her defenses are up, there’s a wall of fury around her, and her body resists letting it down; if she lets it down, even a little, something will crumble that she might not survive. She’s been through a lot, and although the storm is over, the destruction to her heart has yet to be repaired. Perhaps never will be.

This is not a comedy any more.

Every attempt at friendship is met with anger. “You’re better off this way, trust me,” he says. This is a fucked up family,” Igor says, thinking he’s being “nice.”

To which Anora replies “Did I ask you for your fucking opinion?”

By now, Anora knows that what Igor says is true: Vanya is a spoiled brat, his mother is a cruel bitch, and Toros has been right all along that the annulment would happen. But still, it’s humiliating to feel that she’s put so much trust and hope, that she’s allowed herself to dream, and now to be told that it was worth nothing. Igor doesn’t mean it that way but that’s the only way she can take anything now. She bruised beyond the solace of knowing she’s “better off.”

From here on, your interpretation is as good as mine. As with his other movies, Sean Baker isn’t going to give us answers but allows his characters to unfold, reveal, and touch our hearts in ways that we aren’t quite prepared for. You may see the ending very differently than I did (Mikey Madison has said she’s been amazed at the range of responses she’s heard of, some warmer—often, they come from women—toward Anora than others.) That said, here’s my take:

I see everything that follows the return home as a push/pull, “go away/come back” of emotional opening, then resistance, more opening/more resistance, and a final meeting of souls. Romantic? Maybe, maybe not. But dramatically and emotionally perfect, oh yes.

A key exchange, for me, happens when Igor protests that he was only trying to be “nice” in telling her she’s better off without the Zakharovs. In response, Anora reminds him that he assaulted her: “You attacked me, tied me up, gagged me. You’re psychotic.” And maintains, as cruelly and coldly as if she were throwing a grenade, that “If Garnick wasn’t there, you’da raped me, guaranteed.”

I’m still trying to figure out whether Ani really believes this or is just striking out again, wanting to hurt Igor for his pathetic attempt at being empathic. Either (or both, and many other motivations) are possible. Perhaps she’s come to expect that her body is all that men want, perhaps she still believes (although there’s been plenty of evidence to the contrary) that Igor is a brute, perhaps it’s one more insult flung out of anger, perhaps being held down during the home invasion was truly traumatizing despite her toughness. Anora is one of the most layered female characters I’ve seen in a movie—and playing her required of Mikey Madison not just learning Russian, mastering pole dancing, and perfecting a Brooklyn accent and attitude, but taking her believably through several huge emotional changes. By the end, she’s been used and abused—not by the men in HQ, whose sexuality she has expertise in handling and with whom she exercises choice over what is permitted and not, but by Vanya, Toros, and the Zakharovs. And she’s beginning to realize that Igor sees it that way, too.

Still in fighting mode, his “niceness” is intolerable to her. But Igor is undaunted in his own way, and is genuinely perplexed when Ani accuses him of having wanted to rape her.

“Why would I have raped you?”

Another man might have expressed outrage at an unjust accusation: “What, do you think all men are rapists?” Or “I never would have!” But Igor isn’t defensive like that, he’s confused and possibly a little hurt. And to me, the question is endearing and charming. Ani isn’t about to be disarmed, though, and tells him he has “rape eyes.”

Now that seems truly absurd to him. “I have rape eyes?”

“Yes.”

At this point he feels it’s time to clear this up. “No, I wouldn’t have raped you.”

Ani turns. “Oh yeah... why?”

Again, to Igor it seems like a very strange thing to ask, and not just because he’s unfamiliar with the nuances of English. It’s strange to us, the viewers, too.

“Why what?”

“Why wouldn't you have raped me?”

Igor thinks about it for a moment.

“Because... I'm not a rapist?”

Ani doesn’t know what to do with that one, he’s starting to chip away at her defenses, and she spits out her insult of choice with him: “Nope, because you're a faggot ass bitch.”

This conversation leaves a lot of room for viewers’ interpretations. Is she insulted that he wouldn’t have raped her? And why does Igor’s answer, said with the slight suggestion of a question mark at the end—as though he’s genuinely wondering if that’s a good enough answer for her—trigger her anger? Is she confounded at the existence of such a man?

At least one way of seeing the exchange is that despite it’s serious and disturbing “topic,” it’s really just an unusual version of the “come closer/go away” banter between two people who are drawn to each other (maybe romantically, maybe just as the stirrings of trust in another person) but don’t know what to do about it. Igor admires, sympathizes with, and is endlessly tolerant and good-natured toward Ani, but instead of that breaking Ani’s (well-earned) wall down, it makes her want to smack him up even more. And while the persistence of her anger at the whole situation is understandable, after a while it seems absurd/suspicious that so much venom is directed at Igor, who seems like the only truly nice, respectful guy of the lot that she’s been dealing with over the past weeks.

In any case, I’m pretty sure she actually no longer knows what to make of him, or what she feels about him. (You may see it differently, and I invite your interpretation.)

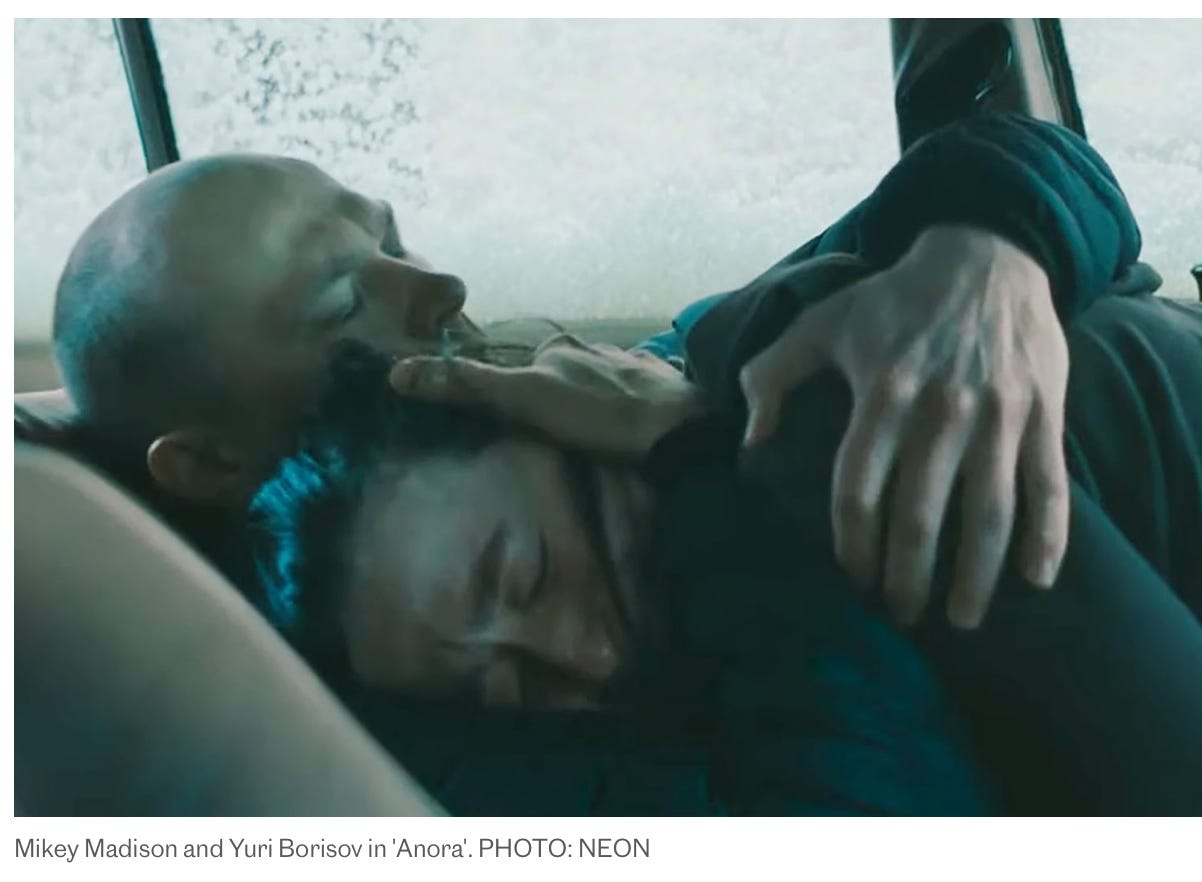

Ani’s confusion deepens the next day, when he drives her home and unexpectedly gives her the expensive wedding ring that Toros had taken from her during the home invasion scene (and which Ani, in a struggle with Igor, had cut his face with.) “Don’t tell Toros,” he says, and lugs her bags up the stairs to her apartment.

It’s snowing heavily, creating a sense of snugness and intimacy inside the car. And when Igor returns, Anora offers what seems like a compliment—the first one she’s ever given him—that is also a recognition that she “sees” him too.

“This car is very you,” she says.

“Do you like it?” He asks, hopefully.

“No.”

“It’s my grandmother’s”

It was fascinating for me to discover that the original screenplay has the “no” coming after “It’s my grandmother’s; do you like it?” Whether it happened in the process of rehearsing or filming or was revised by Baker before that, it’s a change that fundamentally alters how we read the scene. By having Anora’s “no” come before Igor telling her that it’s his grandmother’s car, we’re prompted to read Anora’s actions as she climbs on top of him, opens his pants, takes off her panties, and puts him inside her as more than a way of saying “thanks for the ring” or a reassertion of control. She was already touched by his having kept the ring for her, but she’s still fighting to conquer the emergence, in her, of an emotion that threatens to crack open her defenses against the hurt she feels. So no, dude, I don’t like your car.

But what, now you’re talking about your grandmother? Something is starting to break open, despite her efforts against it.

Initiating sex comes easily to her, while he is taken aback at first. But the intimacy she feels, looking into his face, is something new. She feels seen—and not just because face-to-face is not the usual position she takes with her customers at HQ. The feeling moves things around in her, excites her—and then frightens her. Panting, close to coming (something I believe we haven’t seen in any of her other sexual relations, except perhaps some very obvious performing with Vanya), she suddenly pulls away and begins punching and slapping him. He grabs her arms and stops her, then embraces her, her head against his chest, holding her while she sobs. And sobs. And sobs.

Where will this go? What does it mean for Anora’s future? The movie gives us no clues about that, and for Sean Baker and the actors, answering those questions wasn’t the point but finding the right “energy,” as Yura Borisov puts it, to bring to the scene. Often, words failed Sean Baker himself, and the actors, too, were not entirely sure of what Baker was looking for. “Where are we going? What are we looking for?” Borisov recalls feeling.” They knew only when they found it, not through instruction or explanation, but experimenting and improvising. Borisov goes on to say that verbal instructions are not so important, and certainly not adequate, to create a scene like that:

“We couldn’t discuss the most important part—this special language between people when we’re looking eye to eye and some magic happens. Maybe we couldn’t understand some of the details, but we could understand, ‘Do you feel some fire inside me, and do I feel some fire inside you?’ It’s like a dance together.”

That magic, that dance just took five Oscars last night: Editing, Original Screenplay, Actress, Director, Best Picture. The wins—even though I’d been rooting for “Anora” for weeks—were unexpectedly thrilling. Just a movie. But for me a validation of something. Perhaps, for me, a restoration of faith in the possibility of intelligence and feeling winning at a time when ignorance, cruelty, and brutality are so dominant. Especially after the depression and anxiety that overwhelmed me after Friday’s Oval Office meeting, it was a singular moment of pure delight.

P.S.:

For my thoughts on some other recent movies, see:

A Complete Fiction: Suze Rotolo and the Woman Problem of “A Complete Unknown”

This is not a movie review. This is about mythology. This about how the male gaze seduces us with pleasure, and hides itself behind art. This is about the eclipse of real women. This is a protest song.

And my review of “The Substance” and the under-appreciated “Babygirl”

I think, for example, the scene in which Edward’s lawyer William (Jason Alexander) tries to rape Vivian, slugs her face hard (I winced, even though I’d seen the movie many times before.) After Edward (Gere) comes to her rescue, he doesn’t seem to think a crime has been committed, even after Vivian says she feels like her eye is going to explode. Instead of calling the cops (or even the front desk) he puts ice on her cheek, tells her “not all men hit” (good for you, Edward) and engages in a conversation with William about their relationship. (William: “What is wrong with you ? Come on, Edward ! I gave you ten years ! I devoted my whole life to you !” Edward: “That's bullshit. This is such bullshit ! It's the kill you love, not me! I made you a very rich man doing exactly what you loved. Now get outta here ! Get out ! “)

Trivia: At the end of “The Florida Project,” there’s an escape to Disneyland, too.

Kate Erbland, “The True Story of Pretty Woman’s Original Dark Ending,” Vanity Fair, March 23, 2015)

The term “screwball” is often mistakenly taken as meaning “wacky”—and for sure there are wacky elements in the humor of such comedies. But the term actually comes from baseball, when in the early part of the 20th century it referred to “any pitched ball that moves in an unusual or unexpected way.”) Expected in the classic comedy: the wedding and presumption of happily-ever-after. Unexpected: a cynical, world-wise “undertow” that winks at the naïveté of conventional fantasies.

In preparation for the role of Vivian, Julia Roberts hung out for a day with two sex workers. Mikey Madison immersed herself for months in dance-club culture, lived in Brighton Beach, perfected the Brooklyn accent, and also learned how to do an expert pole dance.

ANORA! ANORA! ANORA! And BORDO! BORDO! BORDO! What a brilliant analysis of film and a gift to everyone who has seen the movie or will see it soon I hope.

On, you make me want to see this movie. I’m not getting out much these days, except with grocery bags or poop bags. But I will see it and return with pleasure to your searching analysis.