Best Episodes from the Best Shows of 2023: “Connor’s Wedding” (Succession) and “Fishes” (The Bear)

Action is fun. But you can’t beat emotion. Will that be the case at Monday night’s Emmys? It’s hard to imagine these two won’t be winners.

The Bear was my favorite series of 2023. The Emmys have put it in the category of “comedy”—which it will probably win—but hilarious as it often was, I never saw it that way. Here’s an excerpt from my review of the show:

Before I watched the second season of “The Bear,” I would have put “Succession” in my top spot among television series. But “The Bear” put into sharp focus what had been nagging me about “Succession” since the first season. Addictive as it was, with the exception of a couple of stand-out episodes—Logan’s death, Siobhan and Tom’s break-up—“Succession” didn’t have much in the way of heart. And what “Succession” lacked, “The Bear” serves up in a second season that no one can mistake as just about the chaos of opening a restaurant.

Succession” was a great show. But it lent itself to a kind of shallow nastiness among fans and reviewers, who preferred to debate about who won the power-game every week than to dive deep into the characters. I was addicted, dazzled, absorbed. But In the end, “The Bear” had my heart.

I’m not sure why more reviewers didn’t “get” how much the show is about what a long, ferocious tail grief has, particularly when that grief is over a beloved person who has hurt you and from whom you’ve become estranged. Maybe the hectic pace of the first season and the cleverness of the writing was as diverting to those reviewers who saw it as a “show about running a restaurant” as doing the running was to Carmy himself. But grief always catches up with you. Carmy left…time got away from him…and then his brother died. How to “process” that?

In season one, we saw all the characters’ attempts to deny grief and loss (not just of people, but of confidence and hope) by shutting down, running away, keeping their bruises hidden to each other. Season two, as if following coach K’s advice, is about each character’s opening up—to each other and to us. (And of course—not to strain the metaphor—they open up a new restaurant too.) The pace of the show slows way, way down, and we get to know all the main characters more intimately—and tenderly.

That includes Mikey, whose absent presence haunted the first season. In season one, all that we know about Mikey (John Bernthal) is that he was a magnetic, volatile personality who, possibly due to his addiction to painkillers, left his restaurant “The Original Beef of Chicagoland” in ruins, killed himself, and bequeathed the mess to Carmy (Jeremy Allen White.) Carmy, in contrast, is contained and controlled, but we sense there’s a lot being tamped down, and perhaps about to boil over. He lives on Tums and his turmoil is mostly externalized for the viewer in the drama of getting the restaurant and its diverse team cleaned up and in shape. No surprise that lots of reviewers praised The Bear as a realistic look into the stress and chaos of the restaurant business. “You may never get a more extraordinary glimpse inside a restaurant kitchen than this” is the headline of a fairly representative review.

The show always was much more than that. And if you didn’t see that before “Fishes,” that episode should have convinced you.

Most people would probably attribute the power of “Fishes” to Jamie Lee Curtis’s performance as Donna Berzatto, the mother of the Berzatto clan. It was an amazing performance. But I’m sure you’ve read enough about that, and I want to talk instead about what for me was the most moving scene in the episode.

In flashbacks during season one, we had seen how much Mikey’s exuberance and confidence, while overshadowing pretty much everyone else in the room, was adored by his more reserved brother and sister, who expertly put together the braciole while Mikey and Rich entertain.1 At the point where season one begins, however, the pleasures of sibling get-togethers is a thing of the past. Carmy—who was hurt and angry when his brother didn’t want to include him in running The Beef or creating a new restaurant—had been without contact with Mikey for a long while, as he (Carmy) pursued a career as a chef. Inheriting the restaurant has brought him home—but no longer integrated in the family, and seemingly detached from Mikey’s death too. (He didn’t go to the funeral, and when Sydney, who applies to work at the restaurant, asks what accomplished Carmen “is doing here”—at The Beef—he tersely replies: “making sandwiches.”)

That’s just on the surface, though—he’s not only grieving over his brother throughout the season, trying to keep him alive through his frenetic attempt to revamp the restaurant, but he’s still haunted by what he experienced as Mikey’s rejection; he joins Al-Anon in part in order to figure out who his brother was in those last years. Then, in “Fishes”—the centerpiece of which is most horrendous family dinner you’ll ever see or are likely to see (even though I’m sure there will be twinges of non-fictional recognition, particularly if you’re Jewish or Italian)—we get the reality behind what Carm has brooded about.

It’s not in the famous dinner table explosion, where we see a big part of why Carmen, Natalie and Michael find it so difficult to be happy with themselves. Perhaps the worst burden a child can grow up with is being constantly reminded of your inability to save those you love and depend on the most. They all try, but their mother’s needs are a mass of contradictions and a bottomless tunnel that twists and turns out of reach nomatter what they do. Leave her alone and she feels unappreciated; ask if she’s okay and she goes into a fury (“What am I, a child?” “Are you asking anyone else if they’re ok?”)

It’s an episode that’s painful to watch. But in a moment of escape from the screaming and recriminations, Mikey and Carmy are alone together (in search of saltines for Rich’s wife, who’s pregnant and nauseous) and one wishes that somehow Carmy had been able to take into himself what is clearly his brother’s love—to take that love into his heart and keep it there.

MIKEY: Saltines? You're kinda acting like

a saltine, you know that?

Why? Why?

What's going on with you?

I know there's something.

Just tell me. Come on, Carm,

I'm right here.

What's going on?

I gotta drag it outta you?CARM:-I just...

I just, I thought,I thought when I was back,

I could work with you, alright?

At the spot.

We could talk about the shop, 'cause I've been

learning a lot of shit,

and, I don't know, I feel like I got some ideas.

MIKE: Yeah, but... (stammers)

The place is no good, Carmy.

It's-it's a fucking nightmare.

-Like, trust me, I'm doing you a favor.

And I'd love to hear your ideas.

I would. I-I-I wanna hear

about you, I do.

CARM: Also I don't need

you talking to Claire

and acting all nice if you

don't actually give a fuck.

You know?

MIKEY: Wh-what?

What are you talking about

I-I don't give a fuck?

Why would you say that to me?

Carmy, I give like a... I give like a huge fuck.

CARM-Yeah?MIKEY-Yeah. fuck, yeah. I mean, I give... I-I...

I give like the biggest fuck. Alright?

CARMY; Okay.

I um, I got you... I got, uh, it's stupid.

I got you...Actually, I got you something.

-Can I give it to you?MIKEY-What, you got me a present?

CARMY: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

I got you a present.

Just one second.

MIKEY: Alright.

Wait, before I, uh... why don't you give me, like,

like, three things about Copenhagen, man?

Anything.

CARM: It's the most beautiful place

I've ever seen.

MIKEY: Yeah.

CARM: Uh... I slept on a boat.

And, uh... I fed an invisible cat.

MIKEY: Hmm. Well, Carm...that's a home run. Out of the park.

Alright, go ahead.

Go ahead, go ahead.

What is this?

Oh, Carmy, that's a...

CARM: It's like, it's like

a little bit rough,

but I don't know, it's something--

MIKEY No, man, that's... It's beautiful. That's...

That's perfect.

CARM: Yeah, Mike, we could, um... We could do this, you know.

MIKE: Yeah.

-CARMY: Yeah.

MIKEY: Yeah, let it rip.

CARM: Yeah, let it rip.

MIKEY: Yeah, Carm.

It’s a sketch of the restaurant Carmy hopes he and Michael will run together. Later, we see it framed, hanging on the wall of The Beef.

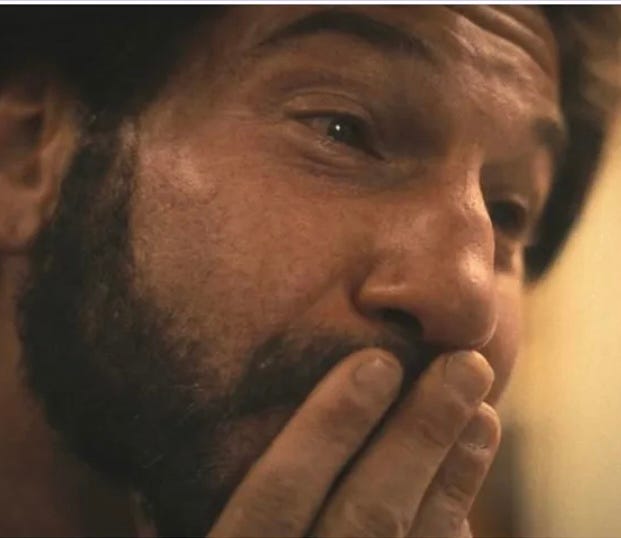

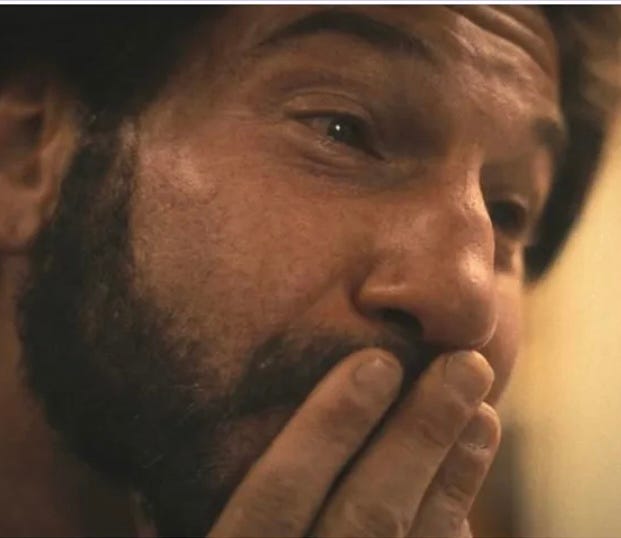

Donna calls out and Carmy leaves the pantry with the saltines. What he doesn’t see is Mikey, alone, leaning against the wall of the pantry, crying.

Adapted from:

Logan’s Death: The Genius of Tolstoy and the Brilliance of Jesse Armstrong (an excerpt from my 4/9 post):

Many people who have read “The Death of Ivan Ilych “ (and many who haven’t) believe the novella begins with the memorable words: Many people who have read “The Death of Ivan Ilych “ (and many who haven’t) believe the novella begins with the memorable words:

“Ivan Ilych’s life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.”

But actually, that famous line is at the beginning of the second chapter. The first chapter is entirely about the reactions of family and colleagues to Ivan Ilych’s death. As they “pay respects,” there are awkward moments, dealt with by conventional expressions of sympathy, followed by more awkwardness:

“Peter Ivanovich, like everyone else on such occasions, entered feeling uncertain what he would have to do. All he knew was that at such times it is always safe to cross oneself. But he was not quite sure whether one should make obeisances while doing so. He therefore adopted a middle course. On entering the room he began crossing himself and made a slight movement resembling a bow. At the same time, as far as the motion of his head and arm allowed, he surveyed the room.”

There are discussions of whether or not the event of Ivan Ilych’s death should interupt the bridge game scheduled for that evening. (It doesn’t.) There are calculations on the part of Ivan’s wife as to whether and when to weep, as she questions Peter Ivanovich about her financial situation. And there are conjectures as to who will be given Ivan’s post: “On receiving the news of Ivan Ilych’s death, the first thought of each of the gentlemen in that private room was of the changes and promotions it might occasion among themselves or their acquaintances.”

This first chapter of The Death of Ivan Ilych is, on the one hand, a blistering look at the hypocrisy and self-orientation of Ivan’s family and colleagues. But on the other hand, their reactions are so familiar, so recognizably human that what could easily be dismissed by the reader as “not me! I wouldn’t respond that way!” becomes a window onto the scared, denying, selfish, awkwardly-flailing-about corners of all our souls. A good deal of Sunday’s episode of “Succession” was like a modernization of that opening chapter. Some characters say the stupid, stumbling, conventional things (“So sorry for your loss.”) Others are distracted by thoughts of the consequences for their own futures. There is talk of whether or not to cancel Connor’s wedding (“I think it’s cancelled,” says Willa; she and Connor marry anyway, but in a low-key, sparsely attended ceremony.)

Everyone has trouble knowing what to say and do when someone has died. In the case of “Succession,” that awkwardness is compounded by three facts: One is the fact that Logan is a public figure whose death will affect the world outside the family (at one point, Roman points to the descending stock market and says, “There’s Dad’s death”.) Another is the fact that he’s not just the kids’ father (or Tom’s or Gerri’s or Kerry’s employer); Logan’s fortunes have been their fortunes, and his whims have decided their futures. Their lives, even though they are grown-ups, are as entwined with Logan’s and dependent on him as children. And last and most significant for the impact of this past week’s episode: The kids love their father, yes, but he’s also been heartlessly cruel to each one of them. And now he’s dying.

Logan Roy’s death itself is nothing like Ivan Ilych’s. Ivan had been suffering from a long, drawn-out illness (unidentified but variously diagnosed by different commentators, most often as cancer.) Logan, although he’s suffered from health issues during past seasons, has seemed as fierce and forceful as ever—perhaps, looking back at last week’s episode, suspiciously more than usual, as he mounts a pile of boxes to deliver a slightly unhinged fight call to his ATN employees. (His final words as he’s mounting the stairs of the plane: “Clean out the stalls, strategic refocus. A bit more fucking aggressive.” ) When he dies unexpectedly, perhaps of a stroke, perhaps a heart attack, on route to the meeting where he is about to close (or not) on a major deal that will decide the future of Waystar Royco, those of us watching the show are as shocked as the family (and for a good chunk of the episode, as uncertain about whether Logan has died or not.) The viewer, as director Mark Mylod has described it aptly, is “hijacked in exactly the same way as the siblings are when they hear the news, so we’re immediately parachuted into their emotional experience.”

“Hijacked” and “parachuted.” Perfect metaphors. That Logan’s death comes so early in the last season (and off-stage, in the bathroom of a plane headed to meet with tech-mogul Mattson) is, in itself, a stroke of genius on the part of the writer Jesse Armstrong—and not just because it provides the show with a surprise that upends convention about killing off stars early (much in the way that Janet Leigh’s death early in Psycho did) but because it avoids a culminating death scene after which we’d all be wondering what happens next.

Logan is no tragic hero whose death signals the end of someone flawed but noble and allows for unambivalent mourning. We never really get to know him, his motivations, or what he’s planning. And that opaqueness is integral to the character and to the responses of those around him. Like Henry VIII, who can declare his love one moment and remove a head the next, he counts on others skating carefully on the thin ice of his approval, all the better to manipulate them. His kids, on the other hand, are as transparent (and as fragile) as glass, even when they don’t know themselves what they’re feeling or doing, and it’s their story that’s the true tragedy (and comedy) of the series. And nowhere is this clearer than in this episode.

Their ambivalence toward their father is vividly described by another fan of the show, Michelle Orr, who posted this morning:

“Thank you x 1.000.000, for deeply capturing the moment a child loses a parent they both love and were abused by. The reaction was quite palatable— confused that you feel deep sorrow for someone who was so cruel yet had moments when their love shined on you like there was no other star in the sky.

Children of abuse have a hard time understanding their emotions towards abusive parents even as adults ….

And also the moment when we imagine what we will someday say to such parent is completely taken away from us.

Tom, for all his faults practiced a lot of grace in allowing the children to speak to their father (albeit in the most awkward of ways) in his last moments.

These moments are not for the dying but for the living.

No everyone has the courage to tell their abuser that they both love and hate them.

Thank you writers and actors for this episode. Probably the best television I have ever seen.”

Like the opening of Ivan Ilych, this episode is about the living, not the dying. And if anyone wondered whether Shiv and Kendall’s alienation from their father has turned their hearts to stone, this episode rejects that possibility definitively. As I discussed briefly in last week’s post on the show, we don’t know exactly what their childhoods were like. But we do know they’ve spent most of their adult lives trying to please Logan, trying to get that sun to shine on them, and only began to plot against him when they felt utterly betrayed. And fury at a still-living parent doesn’t protect against devastation when he dies. As they talk on the telephone to a father who they suspect is dying (but are not sure is dying) Shiv and Kendall are torn in both directions: They want Logan to know they love him—and we realize, perhaps with certainty for the first time, that they truly do—but they can’t suppress the “despite everything.” They want him to know they don’t forgive him, even though they love him—which is absolutely where they are at. To pretend otherwise would be a kind of self-eradication.

And besides, they aren’t sure that Logan won’t live. Neither are we; we spend a good deal of the episode suspended between the possibility that he will still come around (“What’s happening here? Where’s the Swede?”) and the growing realization that he’s gone.

Pretty fucking brilliant, Jesse Armstrong.

Excerpted from:

Siobhan Roy Reacts to Logan’s Death

In “Connor’s Wedding,” Siobhan’s reactions to Logan’s death brought out the anti-Siobhan venom that I’d been chronicling during the season, and showed (to my mind) how mistaken it was.

When Shiv was first informed of Logan’s (probable, at that point) death, she responded in a way that had the anti-Shiv bile spilling all over Facebook and Twitter:

“No! No! I can’t have that.”

What a spoiled brat, Always about her. The selfish, over-privileged princess.

Now that we know for sure that Shiv is pregnant (from that cruel last sex-game with Tom, in Italy) it’s possible—I would say likely—to understand her words in a different way.

Siobhan has, for the first time, something that she knows for sure will please her father. And she doesn’t even get the chance to tell him. “No. I can’t have that.” And a bit later, on the phone with an unconscious Logan: “Not now.” Maybe it’s just because she said vicious things to him the night before. But maybe, too, the “now” refers to her pregnancy.

The next day, on the stairs with Tom:

“I guess I'm just, uh, slowly coming to accept that... we killed him. No, we did. He died on the plane… And he wouldn't have been on the plane, except that we made him get on there…. If we had said yes to GoJo, then..... he might've been around for 20 more years. So he could rock his grandkids to sleep.”

Tom, sarcastically: “As he was evidently so keen to do. “

Shiv: “Yeah. Well, that's fսckеd now, isn't it?”

“I'm angry. My dad died. And my mom is a fսcking disaster. And my husband is... And Kerry, and Marcia, and... It... it... it feels like I'm the only one who lost something that they actually fսcking wanted here and it's not coming back, so...”

The anti-Shiv armies on Facebook and Twitter (and there are far, far more of them than for Kendall or Roman, both of whom are appreciated for their complexity and moments of vulnerability,) were quick to overlook that Shiv is the only one of the three expressing regret over their final power-play with their father—as well as the only one lamenting the loss of the sibling’s temporary unity when they begin squabbling over the COEship (“It's felt good. Us, right?” She says to Roman, “And now, does this... feel good? Like, does that feel good?) On thread after thread, she was berated and hated for thinking she was “the only one” who felt a loss—and over the fucking CEO position, the cold bitch.

Were you not listening? Shiv has just spoken of her guilt over Logan’s death, and the grandchildren he might have had. And while Tom mocks the idea that Logan cared about that, Shiv may know more than Tom does about her father. Skeptics may find the idea that Logan is interested in grandchildren unlikely, given how abusive he’s been to his sons and daughter. And then too there’s the way he orders Kendall’s son to “get in here” at Thanksgiving dinner, and accidentally hits him when they struggle (it’s not the only time a kid gets accidentally struck by Logan—Roman does, and so does Shiv.) Logan is scornful over the boy’s sensitivity. “He has trouble with transitions?” What a pussy.

But that’s when he’s disobeyed. When he’s in control, Logan can be tender, as he is with the same grandson the morning after Kendall is saved from drowning. “Are you all right, son? Your dad was okay, you know. He was okay.” They’re sitting close together and he’s reading to the boy from “Goodbye Mog,” a sentimental children’s picture book. Of course, that kind of reading matter will never do. Too babyish, not enough masculine action. But still. He’s behaving like a grandpa.

“Pinkie” knows both sides of Logan: both the shaft of light through the window and the darkness of his rages. And she knows that a new baby is the one thing she can give him that he can unambivalently love—at least for awhile. She was the baby of the family herself once, and I’m guessing that as long as she did as she was told, Logan probably pampered her as he couldn’t pamper the boys (lest they turn out to be pussies.) It couldn’t last; she soon got the message that to be respected you couldn’t be a little girl. But that’s exactly what she becomes again, leaving a message to a father that he is probably unable to hear it. All of them have trouble expressing their feelings to Logan, leaving their awkward little speeches about not forgiving him but loving him “in spite of” that. But Siobhan literally sheds decades of armor, fingers trembling, her voice pitched an octave or two higher than usual. The boys call him “dad”; she calls him “daddy.” Her hands suddenly look like those of a little girl, and she can barely operate the phone.

Excerpted from:

Watching this scene again after learning more about the family in the second season, I imagine Mikey was also an antidote to their mother’s depression. What Carmy didn’t know at the time was that Mikey was wrestling with his own.

At the risk of losing your respect for me as a culture commentator, I confess that I have not yet watched The Bear. The upside is I have a lot to look forward to.

I do consider myself a Succession aficionado. You may be right that the Wedding is better art than the Funeral. That said, with regard to the Funeral, I can't recall a TV episode that was so effective at making me forget I was watching a fictional event rather than a real one. l i was actually there mourning Logan. The Wedding was more jarring, but it didn't suspend my disbelief like the Funeral did.

Your sister, Mickey, was my clinical supervisor for years. No ambivalence at all,she was a straight up gift to humanity. ❤️