Brown Girl Magic

How Issa Lopez and Kali Reis Make “Night Country” a Compelling “Reinvention” of “True Detective”

“I believe that every storyteller has a very specific, peculiar, and unique relation to the stories they create…I wrote this with profound love for [“True Detective” Season One] and love for the people that loved it. And it is a reinvention, and it is different, and it’s done with the idea of sitting down around the fire, and [let’s] have some fun and have some feelings and have some thoughts. And anybody that wants to join is welcome.”

“As a Mexican, our survival tool in the face of horror is both beauty and laughter. That’s how we cope with it…. The most salient feature of Mexican culture is how we laugh and celebrate death and bones.”

(Issa Lopez)

You don’t have to sit down around the fire with Issa Lopez, the showrunner of “True Detective: Night Country.” It’s an invitation you can refuse. Some people would rather stay with what they know rather than open up to a “reinvention.” But if you do sit with her, you’ll need the warmth of that fire. It was the first thing that struck me about the new season: what a visceral role the cold and ice and snow played. It’s not just a backdrop, a setting. It’s a constant presence that commands how the characters live—what they wear, how they walk, the difficulties of getting from place to place, the necessity of awareness of where the ice is thick and where it’s just a dangerous glaze over the ocean. And when they go inside into bright, warm rooms, my own body remembered, from living in Canada, how the contrast between outside and inside pervaded life. You could walk from one building on campus to another, and your eyelashes would freeze, your hot coffee cool down. And then you’d go into the welcome relief of the inside. Two totally separate worlds.

I’ve never seen a movie or tv show that made the environment so intrinsic to the story, and that invited the viewer so fully into it. It told me from the beginning that this wasn’t just going to be a detective series that got my brain puzzling and guessing—which is always fun, and there’s plenty of mysteries in “Night Country” to chew over—but one that would engage my emotions, too. And probably scare the hell out of me. When Liz Danvers (Jodie Foster) jumps back from that unexpectedly alive, screaming body, she’s frozen in fright herself; it’s a tiny moment of brilliant acting, and gives us notice that we’re not just going to be weirded out (as in the first season of “True Detective”) but truly spooked.

“Horror is in the blood of Latin-Americans” says Gigi Saul Guerrero, one of the young filmakers who participated in a ComicCon@Home panel called “Latin American Horror Cinema 2: Sometimes They Come Back.” Issa Lopez was a speaker on that panel, too, and she recalls the influence of her grandmother, from whom she learned that the devil lurks in the most mundane forms and settings (“wear your cloak inside out to scare him away” her grandmother told her) and that the veil between the natural world and the world of the dead is tissue-thin. Lopez participated in the panel before HBO called her, inviting her to conceptualize a “True Detective.” But she’d already directed a much-celebrated feature film, “Tigers are Not Afraid,” that I urge everyone reading this to rent (Available on Prime and Shudder.)

Like “Night Country” (and much Latin-American “magical realist” literature) the setting of “Tigers are Not Afraid” is realistic—but continually invaded by extra-ordinary images whose nature is unclear. Hallucinations? Visitations? Metaphors? It’s not the “ontological” status of the disturbances that’s important. What’s important is the belief that “a discourse of undisturbed realism” is inadequate to convey human experience—whether intensely personal (the loss of a loved one), a historical upheaval like war, or social violence and injustice (the abuses of corporations, religious persecution, etc.) And it’s not simply an artistic choice. For Lopez’s grandmother, the lurking devil was a part of her reality. And for cultures that have undergone unimaginable horrors, “the transactions between the extraordinary and the mundane that occur in so much Latin American fiction are not merely a literary technique, but also a mirror of a reality in which the fantastic is frequently part of everyday life."1

In “Tigers Are Not Afraid,” the reality is the Mexican drug wars and its effect on the lives of a group of children running from the cartel that murdered their parents. As in “Night Country,” the shared nightmare overcomes initial hostility, as the children, like Danvers and Navarro, come to protect and rely on each other. Significantly, the hero is a young girl whose mother has been murdered. At first she is disdained by the pretend-macho leader of the all-male pack. But ultimately, she becomes the fiercest warrior of the group.. Like Navarro, she is haunted by the dead. Like Navarro, she is tough/tender with the others.

It wasn’t surprising to see a female warrior antecedent of “Night Country.” But there are more mysterious correspondences. There’s a stuffed tiger beloved by the youngest of the children and the appearance of a living counterpart, an actual tiger. In “Tigers are Not Afraid,” the pair are a reminder of loss (the toy) and the recovery of ones true identity as a warrior (the full-size tiger.) As to the one-eyed polar bear that appears twice in “Night Country,” confronting both Navarro and Danvers in their cars, I’m not sure. Maybe—unless it’s disclosed in the final episode—I’ll never figure that one out. Maybe Lopez wants to keep us intrigued; “I prefer the strange, incomplete answer,” she’s said. “I think there is a fascination with puzzles that are still missing a couple of pieces, and that obsess us, and make us angry, and make us not stop thinking about them.”

It’s of a different order, but I can’t stop thinking about Nic Pizzolatto’s mean-spirited response to “Night Country.” “I had no input. Can’t blame me,” he assured his bros on TikTok—and if you’re worried Matthew (McConaughey) might make an appearance as the ghost of Rust’s dad, no way. What’s going on here?

When Issa Lopez described the first season of “True Detective” as a “masterclass in masculinity,” it was said appreciatively. It was a good thing when male writers, artists, and film-makers finally began to explore themselves as men rather than “Man,” and the first season of “True Detective,” besides being a great thriller, was a highlight in that exploration. At least, that’s how it seemed to me—and Lopez. “It touched a nerve,” she says.

What was that nerve? Partly, it was the slight aura of the mystical injected into a genre that had been so naturalistic. But also, it was the replacement of stale, generic male archetypes with two distinctive, complicated personalities, and watching them tangle with and annoy each other, as under the surface irritations of their different personalities the relationship was evolving into a real attachment.

That’s a motif that’s developed in “Night Country,” too. In fact, Lopez sees it as central: “The forces that draw them [Danvers and Navarro] apart and those that bring them together” form the spine of the show much more than the mystery of what happened to those scientists. The latter keeps us guessing, trying to figure out what missing piece(s) will complete the puzzle/mystery. But for both shows, the relationship between the two detectives is the nerve center:

“When I talked to HBO about the first draft, I was like, deep down, this is a rom-com.These are two characters that love each other, found each other and fell in love, and then fell out of love terribly. Now they’re enemies. And that’s when we meet them. And the show is the story of how they fall back in love. This is friendship. But in the end, it’s the same thing.”

The comment makes me hopeful that “Night Country,” like the first season of “True Detective,” will give us the pleasure of re-uniting that is classic comedy. Surely that’s what Lopez has in mind (not a Tom Hanks/Meg Ryan vehicle) when she refers to a show like “Night Country” as a “rom-com.” The series doesn’t have a whole lot of laughs, but that’s not the essence of classic comedy (as in Greek and Shakespeare.) In classic comedy, things fall apart and then, in the end, come together (often through a wedding, but not necessarily.) It’s about the restoration of union, not about jokes—although there some very funny moments in both seasons. Prior asking “Who’s Mrs. Robinson?” Made me laugh out loud. So did Danver’s attempt to say “Chupacabra,” which had the added delight of making Navarro laugh. And in episode 5, Danvers trying to disguise her spontaneous reaction at hearing Prior’s wife has kicked him out was a great piece of comic acting on Jodie Foster’s part. “That’s hard,” she finally manages to squeeze out, barely containing a twisted smile. Really, she’s sort of gleeful about it; at best, she’s just not very interested. “It’s not a divorce,” he calls out as she’s walking down the hall. Danvers: “Whatever.” That was funny.

I loved the first season of “True Detective,” despite the surplus of naked women and Rust’s pretentious, metaphysical speeches. But after Pizzolato's scornful remarks about how “stupid” Issa Lopez’s “Night Country” is (“I didn’t have any input. Can’t blame me”) I started to wonder. Maybe Pizzolatto had put on a good show, but just how deep did his deconstruction of masculine mythology go? Apparently, not deep enough to be curious about what a detective show that centered female experience had to offer.

I’m pretty sure he’d recoil from Lopez’s description of the relationship between the detectives in both seasons as love stories. I know he found elements of the plot “stupid” (whatever that means.) But Pizzolatto’s reaction was not just masculinist or pompous, it was also very “white.” Or putting it academically for Nic (Pizzolatto was a literature professor before developing “True Detective,” and I suspect that may have something to do with Rust’s flights into high theory) it’s an “ethnocentric” response. Because “Night Country” is not only woman-centric (A woman gives birth in one episode—yuck!) but it was developed and written by a Mexican woman, and far from being an irrelevant bit of biographical information, that arguably explains a lot about what might have put Pizzolatto off. I don’t mean anti-Mexican prejudice. I mean resistance to entering a totally different cultural world.

Ritual totems and staged murder scenes with antlers are just playing with the supernatural. Like “The Yellow King,” they all turn out to teasers, and are actually the work of live human beings. But ghosts pointing the way to a cluster of frozen dead bodies? One-eyed polar bears that may or may not be real? You can see Nic’s eyeballs go skyward. Maybe he imagines himself too much the realist, like Danvers (he’s certainly as curmudgeonly in his comments about “Night Country”) to take such visitations seriously. If so, that’s a big difference between him and Lopez, raised in a culture in which the devil is not just a fiction of guilt-inducing sermons and and death is paid homage to in a special day every year. In the panel I mentioned earlier, Lopez said that she’s always been interested in the “clash between the real world and the dream world.” But by the time she did “Tigers are Not Afraid,” she no longer believed in the firmness of the dichotomy. For many cultures under siege, the “real world” is not a benign place that is occasionally invaded by nightmares. Horror is an everyday thing. And even if you solve the crime, the dead will visit.

Whatever we believe when we have our realist hats on, we all have moments when we feel invaded by the strange, the uncanny, the inexplicable by ordinary means. Hard-headed Liz has those moments too; she just mistaken believes that throwing her son’s toy bear out of the window will make them go away.

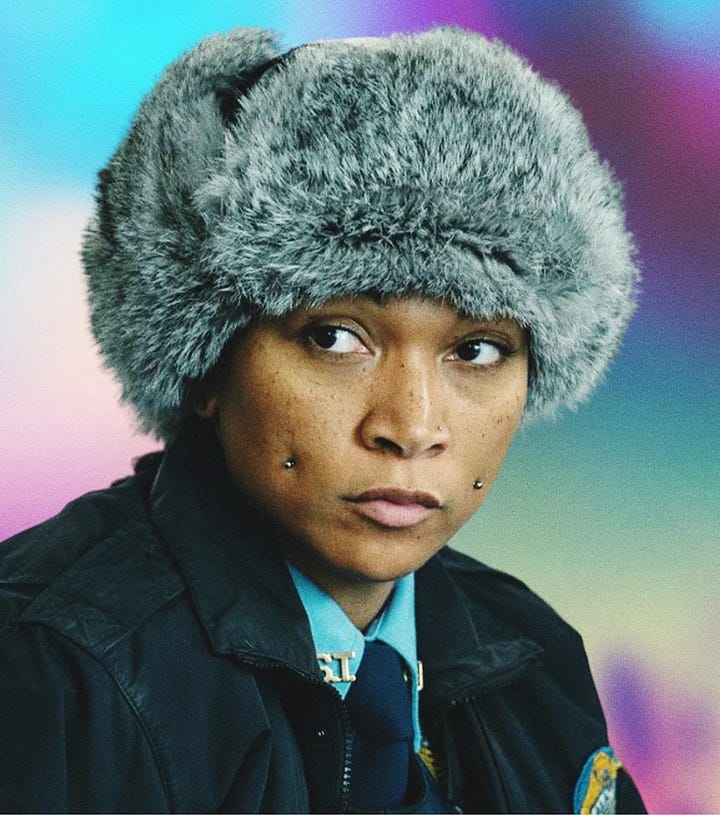

Asking what’s real and what’s not real isn’t the “right question” anyway. “Night Country” isn’t about what’s “real” but about what haunts us: a game played with a dead child, an unsolved murder, questions about who one is and what one stands for. Which brings me to the character of Angeline Navarro, played by Kali Reis, who is possibly the most haunted character of the season—and gives the performance that is most touched by magic. Jodie Foster is a genius actor, and she’s particularly wonderful in the role of Liz Danvers. But Kali Reis’s Navarro is the most compelling presence in “Night Country.”

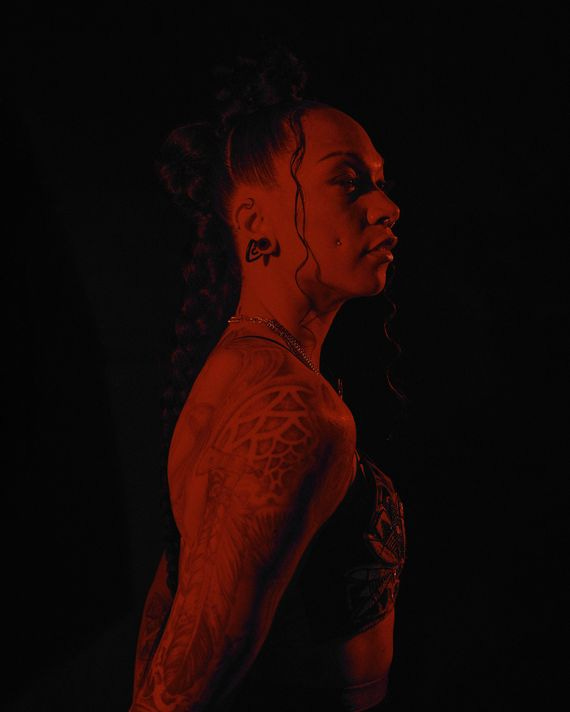

Reis was a boxing champion in two different weight classes and she’s covered in tattoos inspired by her Seaconke Wampanoag and Cape Verdean ancestry. One is her native name. “Mequinonoag,” meaning “many feathers” or “many talents.” (Very apt.) Another is “merciless Indian savage”, pulled from the Declaration of Independence, and meant both ironically and defiantly: “All right, I’ll be your merciless Indian savage,” Reis says of the tattoo. “Be careful what you label me.”

Reis really is beyond labels. I could look at that face all day. As Navarro, who is part Dominican and part Inupiaq, she’s the most divided soul in the show, torn between her duties as a cop—which can require her to subdue protests she believes in—and her deep identification with the people she is sent to arrest. The ambivalence trails her in every call she makes, and Reis is able to convey it virtually wordlessly. In a flashback in episode three, she’s sent to Annie Kowtok’s place to arrest her for destroying local mine property. A new cop at the time, she starts out official and no-nonsense—until she discovers that what she thought would be a resistance hide-out is actually a birthing center, where Annie and four other doulas are guiding a woman through a water birth. “It’s one of the last,” Annie tells her, as Navarro stands there, in a state of uncertainty. What is she supposed to do about this? She’s frozen, caught both by surprise and by something deeper. And when the woman giving birth asks “what’s that bitch doing here?”and Annie replies, “She’s helping,” it’s a pivotal moment. Without hesitating and without a saying anything Navarro joins the doulas, bringing hot water and chanting with them.

We don’t know much about Navarro’s personal life up until this point, only that she’s had sexual relationships with both men and women, and—more significantly—that her mother never told her her Inupiaq name. It’s a fragile piece of her identity that’s eventually going to become much stronger, and Annie’s death will be instrumental in that happening. But in this scene, it’s as though she’s introduced to the Inupiaq community of women for the first time. Slightly dazed, she discards her cop-ness and melds with the others like a little girl being welcomed into the secrets of a warm new world, and when the baby is born, we see a a shy smile, then anxiety when the baby doesn’t cry. There have been numerous stillbirths in Ennis, and they are all primed for another. But this one does live, and Navarro is as joyous as the rest. Annie, ready now to be arrested, holds her wrists out.

We aren’t shown what Navarro does in response to Annie’s offered wrists, and it’s exactly right that Lopez doesn’t reveal it—because it’s a moment when Navarro herself doesn’t know who she is. But we do know, from the preceding episodes, that she must have grown close with Annie, because she says at one point that she believed she “knew everything about her.” And is determined to find out who killed her.

As Navarro, Reis is the embodiment of what “butch” used to mean (I don’t know if it means anything anymore): a fierce undaunted protector, but in the service of the tenderest of feelings. Both the tough protector and what Reis calls the “vulnerable mush” side of Navarro came naturally to her: She’s “always known, as an Indigenous woman and a woman of color, that we have to protect our women.” (She’s advocated for years for missing and murdered Indigenous women and worked with Native girls in group homes “for as long as I can remember.”) But she also identifies as two-spirit, which she describes as feeling “completely comfortable being my feminine and completely comfortable being my masculine.” So the contrasts in Navarro—the big-shouldered, stoic cop who looks perpetually worried and suspicious and the empathic, tender-hearted, vulnerable softness are there in Reis.

Part of what makes Reis’s performance compelling is how focused and still she is when Navarro is being watchful, or just listening.2 She makes you realize how much of what passes as acting in other actors is often just excessive expression. That doesn’t give the viewer a chance to ponder what the character is thinking. At one point, Jodie Foster said to her, “‘You have this way of looking at people in their eyes in scenes, and you like, suck their soul.” And so much of what Navarro experiences is interior, in private soul-space. When she does open up—in laughter, her two studs deepening the dimples that make you want to pinch her cheeks—or in anger, when she confronts Danvers about abandoning the case (“You’re carrying Annie now”)—or in the simple gesture of climbing into bed with Qavvik, putting her arm around him and touching his beard—it gets to you, because of the taut guardedness she normally embodies. Her hair, usually pulled tight against her scalp in a pony-tail, is let loose in episode 5, and the “feminine”/spiritual/emotional release it represents takes your breath away.

That’s all for now. For more on “Night Country,” see last week’s stack (link below) And of course I’ll be commenting on the finale!

Ghosts

The dead are dead,” Liz Danvers (Jodi Foster) insists. “There’s nothing except us. We’re here, Navarro—alone. The dead are fucking gone.” Except at that moment, Danvers is proving herself wrong, as she throws Holden’s toy polar-bear out the door, trying to convince Navarro—and herself—that she means what she says. But it isn’t that easy to banish the de…

Kakutani, Michiko (February 24, 1989). "Critic's Notebook: Telling Truth Through Fantasy: Rushdie's Magic Realism". The New York Times.

“Asking what’s real and what’s not real isn’t the ‘right question’ anyway. ‘Night Country’ isn’t about what’s ‘real’ but about what haunts us: a game played with a dead child, an unsolved murder, questions about who one is and what one stands for. ”

This. All of this. It's a different kind of storytelling -- a kind of visceral narrative -- which doesn't fit the usual master narratives in which we've been raised. And when we don't have the right discourse for it, we defer to words like "atmospheric" and "moody." But we know how it feels, at least.

I appreciate your perspective on Night Country. I've watched every episode but find it slow, ponderous, and depressing, yet I keep watching because of the acting by Foster and Reis, and because I'm hoping there will be an answer to the various mysteries that are interwoven into the series. I'll watch the finale with greater appreciation than before.