Deconstructing Elizabeth Zott, Part 2: How to Make a Woman Scientist Disappear

“Lessons in Chemistry” is both more accurate—and more of a fantasy—than you might think.

“By choice she did not emphasize her feminine qualities. Though her features were strong, she was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes. This she did not. There was never lipstick to contrast with her straight black hair, while at the age of thirty-one her dresses showed all the imagination of English blue-stocking adolescents. So it was quite easy to imagine her the product of an unsatisfied mother who unduly stressed the desirability of professional careers that could save bright girls from marriages to dull men. But this was not the case. Her dedicated, austere life could not be thus explained—she was the daughter of a solidly comfortable, erudite banking family. Clearly Rosy had to go or be put in her place. The former was obviously preferable because, given her belligerent moods, it would be very difficult for Maurice to maintain a dominant position that would allow him to think unhindered about DNA.

Unfortunately, Maurice could not see any decent way to give Rosy the boot. To start with, she had been given to think that she had a position for several years. Also, there was no denying she had a good brain. If she could only keep her emotions under control, there would be a good chance that she could really help him. But merely wishing for relations to improve was taking something of a gamble, for Cal Tech’s fabulous chemist Linus Pauling was not subject to the confines of British fair play. Sooner or later Linus, who had just turned fifty, was bound to try for the most important of all scientific prizes….

But at least Pauling was six thousand miles away…The real problem, then, was Rosy. The thought could not be avoided that the best home for a feminist was in another person’s lab.”

— The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA by James D. Watson

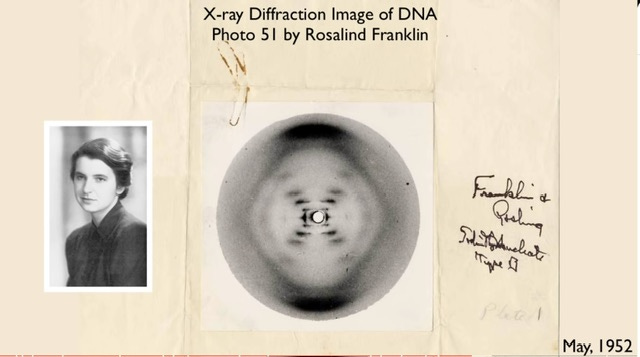

“She had been getting remarkable results. The only researcher working at high humidity, determined to get the best possible photographs before embarking on interpretation, she took sharp clear pictures that revealed something no one had noticed before. There were two forms of DNA. When hydrated, the fibre became longer and thinner. When placed over a drying agent, it changed back. This transformation explained why Astbury’s patterns had been difficult to interpret further. All earlier attempts to understand DNA’s structure had been looking at a blur of the two forms. Rosalind and Gosling were tremendously excited by this finding. They called the new, longer, thinner, heavily hydrated DNA, ‘wet’, or ‘paracrystalline’ or, more simply, the ‘B’ form. The other, shorter, drier alternative, which they could reproduce at will, was ‘dry’, ‘crystalline’ or the ‘A’ form. This achievement was essential to the great discovery that lay in wait. Rosalind’s skill in chemical preparation and X-ray analysis that Bernal later called ‘among the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken’ had given the first clear picture of DNA in the form in which the molecule opens up to replicate itself.”

— Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA by Brenda Maddox

““Nothing earth-shattering.” That’s how Donatti had described his article a few months back. But the work was earth-shattering, and she should know. Because it was hers. She read the article twice just to make sure. The first time, slowly. But the second time she dashed through it until her blood pressure skipped through her veins like an unsecured fire hose. This article was a direct theft from her files. “I’m sorry,” he pleaded. “I really am. I had no idea Donatti would go this far. He photocopied all your files the first day you were back, but I assumed it was to familiarize himself with our work.” “Our work?” She managed not to reach out and snap his neck in two. “

— Lessons in Chemistry: A Novel by Bonnie Garmus

Early in this past week’s episode of “Lessons in Chemistry” Elizabeth Zott, who was selling tupperware from her hybrid kitchen/laboratory, dumps a magazine in the wastebasket. It’s a copy of “Scientific American,” and it features a picture of several of her former colleages at Hastings Research, with the headline: “Do These Men Know How Life Began?” Abiogenesis—the study of how complex life arose from simple, non-living forms—has been the focus of her research with Calvin Evans, her lover and soulmate, whose unexpected death provided an unexpected opportunity to freeze Elizabeth out of the research and make it their own. They saw nothing wrong with that. Elizabeth was just a lab tech, not a “real” scientist. And she was a woman. What was she even doing in a laboratory?

Actually, they all knew how brilliant she was, as they’d gone to her whenever they were stuck in their own research. Later in the episode, she’s offered her job back, with the promotion to “junior chemist” and a promise of being listed as “second author” in future publication. After thinking for approximately a nano-second, she leaves the room.

The cover of the magazine Elizabeth throws away is remarkably like the cover of the issue of “Nature” that announced to the world that Cambridge scientists James Watson and Francis Crick, relative newcomers to the world of chemistry, has discovered the structure of the “secret of life”: DNA.

Rosalind Franklin

“ The double helix collusion scheme was nothing short of a plot among men of mutual interests, cultural beliefs, and entitlements. A long trail of conspiratorial dominoes was carefully put in place by the participants long before the Watson and Crick paper was published in Nature. How those dominoes toppled one after another with such precision, and the machinations by Watson, Crick, Wilkins, Randall, Perutz, Kendrew, and Bragg to conceal the fact that the W-C model was predicated on Rosalind Franklin’s data, fits the definition of conspiracy all too well."

― from "The Secret of Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA's Double Helix"“ by Howard Markel

“You’ve got to read this,” my husband said, pushing a copy of James Watson’s 1968 “personal account of the discovery and structure of DNA”—The Double Helix— in my face. I wasn’t very interested. It was the mid-1980’s and besides a 4-5 teaching assignment, I was trying to turn my PhD dissertation into a book. I had quit smoking, was tired and grumpy a lot of the time, and I didn’t want to have DNA explained to me. Numbers terrified me.1

But Edward was persistent, and it turned out it wasn’t the science he was pressing me to read, but Watson’s descriptions of a female colleague, Rosalind Franklin, who had also worked on the structure of DNA, but through x-ray crystallography rather than the theoretical model-building that Watson and Crick were focused on. He’d found Watson’s comments about Franklin outrageous, and he knew I would, too. One of our strongest bonds is that we almost always get worked up about the same things. Edward wanted to share.

I may actually have been even a little less appalled than Edward. Comments on Rosalind’s hair and make-up didn’t surprise me. Even in 1982, when I was writing my doctoral dissertation (in philosophy) and “on the job market” for the first time, my tiny cohort of female graduate students had been given guidance by on how to dress and to make sure, if married, that we took our wedding rings off. I was careful to keep my hair long until the job interviews were over (one was conducted in a hotel room, where I sat in a chair in front of seven or eight men sprawled on the beds, interrogating me about whether my dissertation—on Descartes, gender, and the rise of enlightenment thinking—was “really philosophy.”) I didn’t get that job, but I did get another, at a small Jesuit college in central New York. It was only after I’d accepted the offer that I had my hair cut into the very short, spikey style I’d been wanting for years. A few years later, I was told in secret that when I went up for early tenure, there had been an extended discussion of my tattered “Flashdance” style skirt, then in fashion, which the committee worried signalled a lack of what? modesty? flagrant sexuality? too unconventional? I’m not sure.

The personality qualities Watson attributed to “Rosy” (as they called her, behind her back) weren’t a complete shock either—”belligerant,” “not a trace of warmth,” “rigid,” “sharp,” “emotionally out of control,” and in one scene, apparently (from Watson’s point of view) about to “assault” him. They added up to a discomfort with “unfeminine” behavior that was familiar to me. When I’d applied to graduate school in 1976 the chair of the department had asked “Do you consider yourself an aggressive woman?” (I honestly don’t remember what I answered.) After I passed my comps, a faculty member told me “Your comprehensive exams were so good, I was amazed to see they were written by a woman.” (He was surprised I didn’t go all gooey with gratitude.) When the same faculty member pressed me to date him, and when I refused, humiliated me in front of a room full of male students, the chair “permitted” me to drop out of his class, but insisted I cite the reason as “personality differences.” Later on, after I’d become a faculty member myself, I sat on tenure and promotion meetings in which students frequently described, in their evaluations, how “cold,” “stern,” and “harsh” their female professors were—words never used to describe male faculty, who weren’t expected to be warm and caring, and whose “rigor” was applauded.

James Watson’s casual sexism was nothing new to me. But still, there was something about his sneers that went beyond garden-variety—so much so that one of his editors at Harvard University Press, Joyce Leibowitz (who Watson referred to as “this smart Jewish woman”) insisted that “you have to say something nicer about Rosalind”—which he did, in a few sentences of praise that he tacked onto an epilogue to the book, where they sat uncomfortably, sounding as though written by an entirely different person.

Even more startling than his venom for Franklin was Watson’s openly expressed craving to get her out of the way, put her in her place, “give her the boot.” She wasn’t just irritatingly unfeminine; nor were her “dark” Jewish looks, although not his preference (he went for tall, blue-eyed blondes) completely unappealing to him. The big problem was that she was interfering. Unless she was neutralized “It would be very difficult for Maurice to maintain a dominant position that would allow him to think unhindered about DNA.”

And they succeeded. The neutralization succeeded so well, in fact, that when, in 1967, James Watson gave PhD biology student Nancy Hopkins a draft of the manuscript of The Double Helix to read, it was the first time she’d even heard of Rosalind Franklin. This was, to be clear, 4 years after Watson, Crick and Wilkins had been awarded the Nobel Prize, having set the scientific world buzzing about the possibilities that their discovery of the structure of DNA had opened up. It was lauded as a “flash” discovery: “Scientists had barely agreed that DNA was the stuff of heredity, and they did not understand how it passed along traits,” Kate Zernike writes, “The double helix explained these mechanics-it was in the sequence of the always matching base pairs, and in the ability of DNA to make an exact copy of itself. Having understood this, the infant science of molecular biology was on its way to identifying the code that gave form and function to all of nature.”2

The “flash” couldn’t have happened if Watson and Crick hadn’t been shown, without Rosalind Franklin’s knowledge, an x-ray of hers that has since come to be known as “photo 51.”

The x-ray was empirical evidence for what turned out to be the helical form of DNA, and the instant Watson saw it “my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race. The pattern was unbelievably simpler than those obtained previously (“ A” form). Moreover, the black cross of reflections which dominated the picture could arise only from a helical structure. With the A form, the argument for a helix was never straightforward, and considerable ambiguity existed as to exactly which type of helical symmetry was present. With the B form, however, mere inspection of its X-ray picture gave several of the vital helical parameters. Conceivably, after only a few minutes’ calculations, the number of chains in the molecule could be fixed.”3

Photo 51 was the result of Franklin’s many long, laborious months obtaining clear x-rays (a difficult task in itself) and interpreting the results. But by the time Watson had returned to Cambridge, he had made it his own:

“Before boarding the train, he bought a copy of the next day’s Times to read on the journey home. As the train “jerked toward Cambridge,” he pulled out a pencil from the breast pocket of his woolen jacket. On the edge of the page where the crossword puzzle was printed, he drew from memory the remarkable X-ray photograph that Rosalind Franklin had acquired with skill, sweat, too much radiation exposure, and the shrouded bruises that came from being a woman playing in an all-boys’ game. By the time he finished sketching a rough version of the “B pattern,” it had become his picture.”4

Rosalind Franklin never found out that her co-worker Maurice Wilkins (after telling Watkins that it was “emotional hell” working with her) had gone into her office to pick up a print of the photo to show Watkins. When Watson and Crick showed her the model that they had theorized and constructed, she applauded their achievement and was pleased to have her crystallographic evidence supported by their model. “We all stand on each other’s shoulders,” she remarked. She died at the age of 37 of ovarian cancer (likely caused by exposure to her x-ray machinery), ineligible for the Nobel Prize awarded in 1963 to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins (it isn’t given posthumously) and unaware of the essential role that her photograph had played.

Having died before Watson’s book was published, she also wasn’t in a position to object to his portrait of her as a humorless, lipstick-less shrew who didn’t know how to fix her hair. Those who knew her outside of the laboratory, in Paris, where she often went to visit friends and cook elaborate dinners, knew a very different Rosalind, one who had a “great zest for living,” “took immense trouble over her clothes”, “always wore lipstick” and—shades of Elizabeth Zott!—was a dazzling cook, whose “French-inspired specialties included rabbit or pigeon braised in red wine, roast artichokes with crispy breadcrumbs, and new potatoes simmered in butter rather than British water. All these dishes were accented with lots of olive oil, fresh herbs, shreds of hard, aged Parmesan cheese, basil, and garlic.”5

More cruelly unfair than Watson’s casual sexism is The Double Helix’s commitment to writing Franklin out of the scientific story, by describing her, in the ongoing early debate about the structure of DNA, as fiercely “anti-helical.” His constant refrain about her “anti-helical bias,” was not just incorrect. It turned her into an opponent of the whole enterprise. In his version, not only did photo 51 become Watson’s baby; so was the very notion that DNA was a helix. In fact, as Franklin’s notes show, she was simply cautious about coming to a premature conclusion before all the data had been collected.

There was undoubtedly a gender dimension to her caution:

“Science was taught to girls in a different way than to boys: an intellectual endeavour calling for neatness, thoroughness and repetition rather than excitement and daring….Rosalind Franklin was carefully trained, from childhood on, as a student at St. Paul’s School for Girls, at Cambridge, and especially as a scientist, “never to overstate the case, never to go beyond hard evidence.”6

Watson and Crick—particularly Watson, who never took notes—were virtually the mirror-opposite. Their excitement frequently outran their evidence, and on one crucial occasion, Franklin had showed them the liability of their approach, a humiliation that I believe they never forgave her for.

It was November 21, 1962, and Watson, eager to see what Franklins’s x-ray pictures were showing, attended a lecture of hers. He was inexperienced in the methods of crystallography, and during her lecture his mind wandered, wondering how “Rosy” “would look if she took off her glasses and did something novel with her hair.” Distracted and probably bored and irritated by her lack of “warmth or frivolity,” he hadn’t understood Franklin’s emphasis on what turned out to be an essential ingredient in structure of DNA: that the phosphate groups had to be on the outside of the DNA molecule. Franklin didn’t present this as an earth-shaking “discovery,” but part of the gradual accumulation of data; she wasn’t about to declare anything definitive without further experiments. But her notebooks show clearly that she was imagining various helical structures ‘Either the structure is a big helix or a smaller helix consisting of several chains. The phosphates are on the outside so that phosphate—phosphate inter-helical bonds are disrupted by water.’

The boys were set on building a model, not patiently gathering hard facts, and based on Watson’s faulty recollections of Franklin’s talk, that’s what they did. They posited that DNA was a triple-helix—with the phosphate groups on the inside.

When they showed Franklin their model, she “wasted no time on pleasantries”:

“Where was the water? She pointed out that DNA is a thirsty molecule—soaking up water more than ten times what they had allowed. The phosphates had to be on the outside, encased in a shell of water. If the molecule were as Watson and Crick suggested, how could it hold together? The sodium ions that they had erroneously positioned on the outside would be encased in sheaths of water and thus unavailable for binding.”7

Don’t ask me to explain the science. The key here is that Franklin knew something crucial that Watson and Crick—who had been loudly bragging about their flawed model—did not.. They were humiliated, and told by Sir Lawrence Bragg, then director of the Cavendish Institute at Cambridge, to leave DNA alone (which of course, they didn’t.) And it’s my belief that this incident was the beginning of what Anne Sayre, in her 1975 biography of Franklin, calls the “slow robbery” of Franklin’s contributions to the research on DNA. Within hours, Watson began spreading the false notion that “Rosy did not give a hoot about the creation of the helical theory….since to her mind, there was not a shread of evidence that DNA was helical.” Howard Markel is even blunter than Sayre, describing how later at Choy’s (their favorite restaurant,) “over platters of chop suey, chicken curry, chips, and fried rice, all lubricated with black tea and cheap red wine, Watson and Wilkins engaged in the old-school bonding of men as they conspired to exclude Rosalind Franklin from the DNA hunt.”

For decades, the exclusion was triumphant. Museum exhibits and encyclopedia entries about DNA didn’t include Rosalind Franklin. Linus Pauling, another of the competitors in the race to understand DNA, wrote a commemorative essay giving the credit for Franklin’s photograph and analysis to Maurice Wilkins.The New York Times obituary when Franklin died in 1958 was four paragraphs and didn’t mention her study of DNA. While ironically, it was The Double Helix that gave Franklin a place in the story, it was a vastly diminished and begrudging admission, which emphasized her “anti-helical” bias, and celebrated the “inductive leap” that she was described as unable to make. (It would probably be more accurate to say she was too cautious to make at the time Watkins and Crick pounced on photo 51 and immediately overtook everyone else in the race) Kate Zernike describes its reception:

“The book was published in February 1968 and instantly triumphed, remaining on the New York Times bestseller list for seventeen consecutive weeks (in the company of a book from another Cambridge luminary, Julia Child, author of The French Chef Cookbook). The Double Helix was serialized in the Atlantic, translated into more than two dozen languages, and became a model for popular writing about science. “One has only to pick up the N.Y. Times or turn on the TV to hear of The Double Helix or see the celebrity himself,” Nancy (Hopkins) wrote to Jim’s father, now wintering in Florida. “Any criticism at this point could only be construed as sour grapes.” For all the complaints about how Watson portrayed his competitors, few objected to his sexist portrayal of Franklin as the scolding schoolmarm who refused to wear lipstick or pretty clothes. ….Franklin’s friends would later argue that Watson had stolen photograph 51 and denied her proper credit in the discovery. But at the time, the incident was accepted as a consequence of scientific competition. Franklin could no longer speak for herself; she had died of ovarian cancer in 1958, five years after the discovery and five years before the Nobel Prize went to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins. (Her death spared the Nobel Committee a debate about who most deserved the prize: while it can be won by a maximum of three people, the rules also dictate that prizes cannot be awarded posthumously.”

And it continued. In 2018, Jim Watson, evidently forgetting the admissions of his (forced) epilogue, described her as “a loser … I use the word loser not in the sense she was a lowlife or bad person. She blew it. She blew it! And that sounds like an awful thing to say but she threw it away, that it was—she had no reason to do what she did except she hated the idea that the A form was helical.”8

Watson wasn’t able to make Franklin disappear forever. In 1975, Anne Sayre had corrected the record with her biography of Franklin, and by the early 1980’s, Women’s Studies Departments were doing the same for neglected women scientists, artists, and writers throughout the disciplines. Nancy Hopkins, the graduate student who had never heard of Rosalind Franklin until she read Watson’s book and who went on after she became faculty, to lead a famous fight against gender discrimination at MIT, had come to a different conclusion than she had when she was first given the manuscript. In 1962, she had “no reason to doubt” Watson’s account. He was her mentor, and after all, only describing a common view of women scientists held at the time. In 1984, when she read Sayre’s book, Rosalind Franklin’s life “affirmed what she had begun to suspect: that because women had no legitimate status in science, men could and would continue to take from them. Nancy had bought the idea of the scientist as great thinker, the solitary genius. She was beginning to see how wrong she had been. But even if that was a fiction, the system was built around it. She wondered how many women would ever be allowed to play the role of genius.”9

Fantasyland

““Whenever you start doubting yourself,” [Elizabeth Zott] said, turning back to the audience, “whenever you feel afraid, just remember. Courage is the root of change—and change is what we’re chemically designed to do. So when you wake up tomorrow, make this pledge. No more holding yourself back. No more subscribing to others’ opinions of what you can and cannot achieve. And no more allowing anyone to pigeonhole you into useless categories of sex, race, economic status, and religion. Do not allow your talents to lie dormant, ladies. Design your own future. When you go home today, ask yourself what you will change. And then get started.”

From all over the country women leapt from their sofas and pounded on kitchen tables, calling out in a combination of excitement for her words and heartache for her departure….

“Thanks to all of you,” she said nodding at the audience. “And so for the last time, I’d like to ask your children to set the table. And then I’m going to ask each of you to take a moment and recommit. Challenge yourselves, ladies. Use the laws of chemistry and change the status quo.” Again, the audience rose to its feet, and again the clapping was thunderous. But as Elizabeth turned to go, it was obvious the audience was not going anywhere—not without one last directive. Unsure of how to proceed, she looked to Walter. He motioned with his hand as if he had an idea, then scribbled something on a cue card and held it up for her to see. She nodded, then turned back to the camera. “This concludes your introduction to chemistry,” she announced. “Class dismissed.””

— Lessons in Chemistry: A Novel by Bonnie Garmus

Elizabeth Zott’s fairytale ending (no details, for those who haven’t read the book) is about as far from Rosalind Franklin’s tragic end as can be imagined. And Garmus maintains the book isn’t based on any particular person or persons, but “a love letter to scientists and the scientific brain.” There are so many provocative details, though—Elizabeth’s (deceptively) stern demeanor, born from abuse and constant denigration, her genius at cooking, the fact that Elizabeth is working on DNA (although some years before the double-helix structure was discovered), the stealth appropriation of her research, the magazine cover that she dumps in the trash—it seems that Franklin must be hovering somewhere in Garmus’s mind.

But Garmus wanted the book to be inspiring, not depressing. And wow,it has been. (One high-school teacher is even making her students read it for a class on The American Dream.) “Zott is a catalyst,” she’s said. “She’s actively breaking and creating new bonds. And that is chemistry at its most basic.” She’s been both surprised and delighted to find that “people have quit their jobs and gone back to school or people have gotten divorced because they recognize themselves. Sometimes I want to say, ‘You know it’s fiction, right?’ But on the other hand, it was what I was trying to get across. You can really do what you need to do. You just have to dig in really hard and not expect it to be very easy.”

But. But. Rosalind Franklin “dug in really hard.” And she certainly didn’t expect it to be easy. And while this is 2023—not 1963—”the American Dream” is still as much a fantasy for most people as it ever has been, with some new (or perhaps, more accurately, revived and refurbished) obstacles in the way of the “female empowerment” that one reviewer described as “baked into every episode” of “Lessons in Chemistry.”

And maybe, in this bizarre and retrograde period in which books about sex and gender are being banned and feminist courses attacked, Rosalind Franklin’s real-life story as well as Elizabeth Zotts fictional one should have a place.

(If you enjoyed this post, please do read Part One of “Deconstructing Elizabeth Zott”. And consider subscribing to BordoLines. Free is absolutely fine and much appreciated but paid would be GREAT—and with all my earnings going to the Brigid Alliance, will help a bit in empowering girls and women to—as Garmus puts it—“do what they need to do.”)

I’m pretty terrified of science, too. Many, many thanks to

for checking this section to make sure I didn’t make any egregious errors!The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science, by Kate Zernike

The Double Helix, by James D. Watson

The Secret of Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA's Double Helix by Howard Markel :

Markel

Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, by Brenda Maddox

Maddox

Markel

Zernicke

This infuriating and deeply researched story brings back memories. I spent the summer of 1968 washing test tubes and beakers in Watson's lab. A stickler for detail, he interviewed me personally. He radiated impatience and competitive zeal. One woman scientist worked in that lab, and the men didn't have much to do with her. In the lunch room she would sit with me and the dour Swedish woman who supervised the washing protocol. The three of us talked about WAIT UNTIL DARK while the men talked science. I now wonder if this kind, lively woman was Nancy Hopkins. I can't find any photos online of Nancy Hopkins in her youth but her face in later years is vaguely familiar.

Victor K. McElheny, in his book WATSON AND DNA, quotes a wide range of Watson's colleagues to fascinating effect. One, Edward Wilson, called him "the Caligula of biology." Wilson also compared the discovery of DNA to "a lightning flash, like knowledge from the gods," and said that if not for his supposed ownership of this breakthrough, Watson "would have been treated at Harvard as one more gifted eccentric." Wilson envied Watson but also called him the most unpleasant person he'd ever met in his career. And he didn't know the half of it.

Excellent piece about a sickening story.

While any ripoff/credit grab burns one or more victims directly, this one feels far more heinous than most, because the weasels in question also burned all women by sleazily airbrushing this one out of our collective history.

Prejudice always involves lying, at its core, and it ought to be understood that in addition to the popular discussion about how prejudice makes you a bad person, it also makes you a childlike person who’s too ignorant and too scared to accept basic reality.

Thanks for doing the work here, for all of us who prefer truth to horseshit. And well-written truth-- that’s even better.