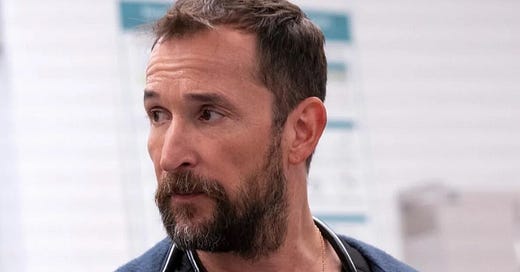

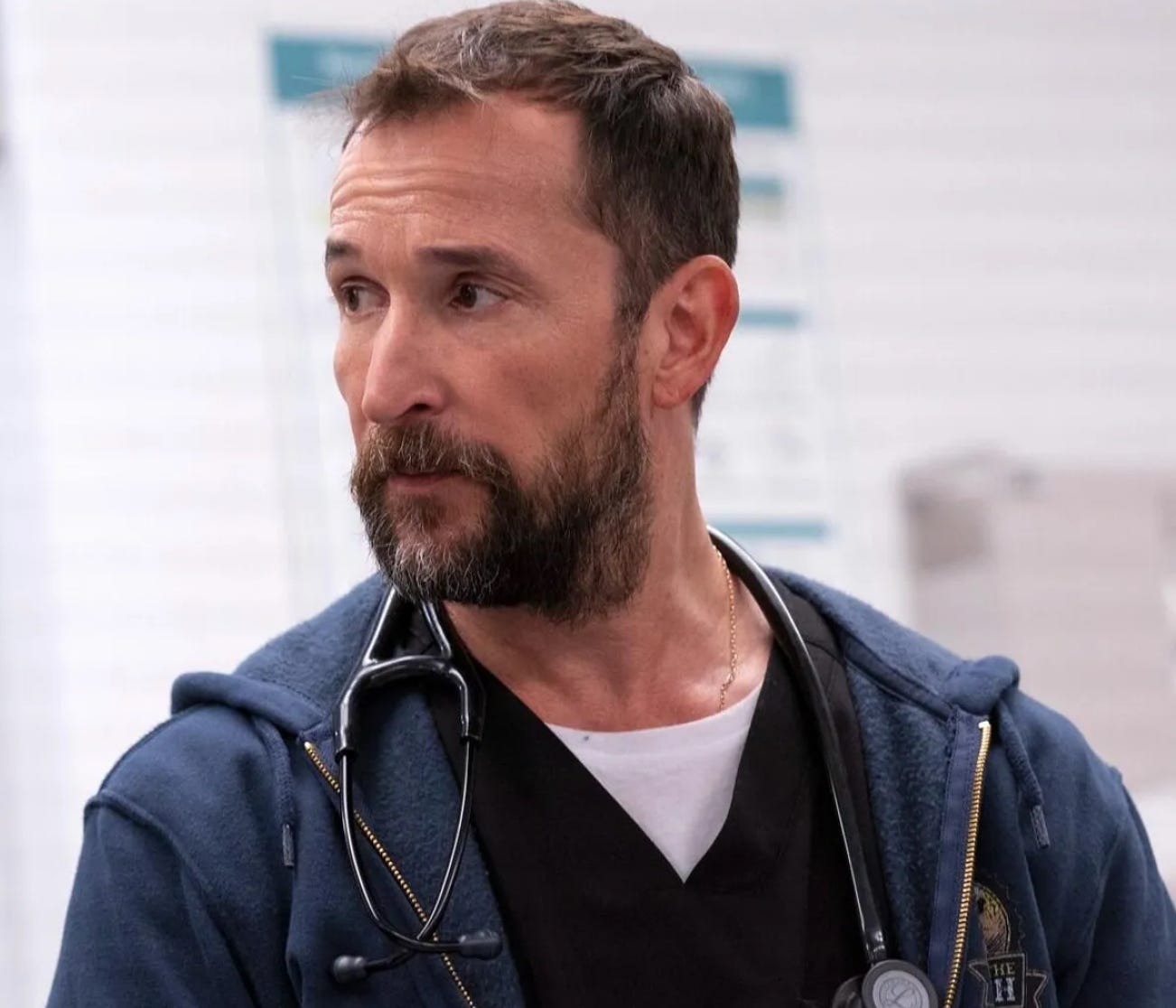

Doctor Robby

Undeniably masculine but infinitely caring with those who are suffering, his working-class ruggedness as much as part of him as his tenderness, Noah Wyle’s Doctor Robby is something else.

1.

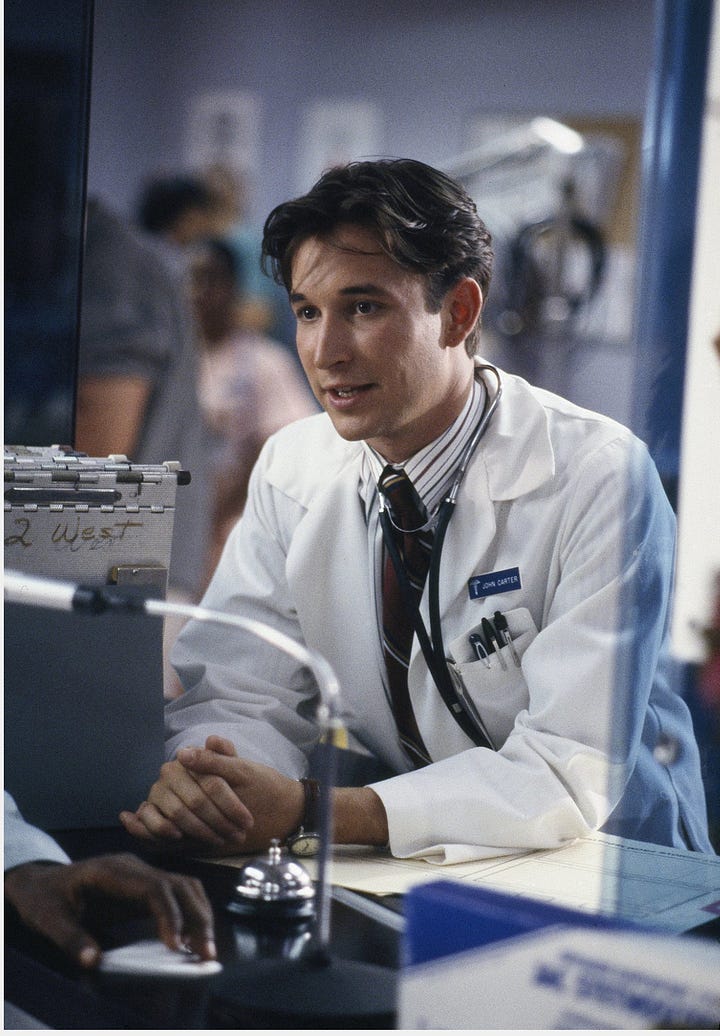

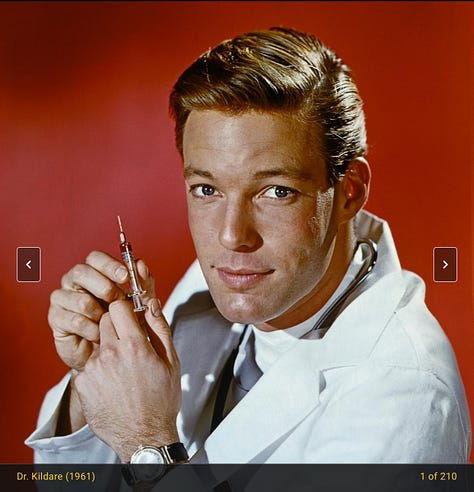

When he played John Carter in “ER,” he was not my type. He was not just too baby-faced, he was also too “cooked” (referencing Claude Levi-Strauss here): too smoothed out by civilization, good manners, rule-following. I went for the more “raw,” surly, often ethnic types. In “ER,” that would have been Eriq LeSalle. In earlier doctor shows, it would have been the brooding Ben Casey (Vince Edwards, who many of you probably haven’t even heard of) rather than everyone’s WASP dreamboat, Young Dr. Kildare (Richard Chamberlin, who recently died.)

My libido was shaped, as it is for many rebellious girls of my generation, by an attraction for the untamed, accompanied by the fantasy of taming the beast. Crazy to imagine that. But not from nowhere: Fictions like Picnic had promised us that there would be vulnerability underneath the macho bravado, and you would be the one to release it, like Stella of Streetcar, who brought out the little boy in Stanley (Marlon Brando).

I liked bad boys, boys whose gristle hadn’t yet been marinated by gentlemanly ideals.

It’s also true, unfortunately, that the raw, untamed boys were also the ones who treated me badly, and I know I’m not alone in that.

I don’t know exactly when I discovered that tenderness and caring were sexy. It may have been when I was (briefly) pregnant, and my passionate Italian lover cooked me veal scallopini and brought it to me in bed, where I was half-dozing, listening to him humming as he moved around the downstairs kitchen.

John Carter in “ER” was written to be a blue-blooded privileged WASP. I had no idea that Noah Wyle was himself Jewish. If I had known, it wouldn’t have mattered much to me then. But in 2025, it’s come to matter very much. Dr. Mark Greene (Anthony Edwards) was Jewish, too—in the “ER” role, not the actor himself—but I don’t even remember how I came to know that, as it played no part at all in the series. But Dr. Robby not only has the unassimilated name (Robinavitch) and the rabbinical beard, but (for me, anyway), he’s the first fictional Jewish doctor to embody Jewish masculinity rather than a nerdy, “feminized” stereotype (or a too-forced attempt to refute it.) And in no small part that’s because Noah Wyle is Jewish himself—and in this role, unlike the role of John Carter, he’s able to lean into his Jewishness, physically as well as spiritually. And oh my god, is it sexy.

Undeniably masculine but infinitely caring with those who are suffering, his working-class ruggedness as much as part of him as his tenderness, Dr. Robby is a gift to us Jews, especially at this time when we feel so despised, when the simmering tropes and stereotypes are hatching from the mud every day.

Some of what we’re given by the show has special meaning for us. When Robby collapses on the floor of the “family room,” overwhelmed by exhaustion, grief, and pain over not having been able to save his stepson’s girlfriend, he tries to comfort himself with the words of the Shema prayer: “Shema Yisrael, adonai eloheinu, adonai echad.” (“Hear O’ Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.”) “Baruch shem malchuto.”

I confess that I had to look that one up. But I didn’t need to consult Wikipedia when, after medical student Dennis Whitaker (Gerran Howell) finds him, Robby’s taken his Magen David (star of David) out from underneath his scrubs and is holding it like a spiritual anchor that’s keeping him from drowning (the word he uses later, describing his experience.) When Whitaker asks Robby about the prayer he was reciting, he says, “It’s a declaration of faith in God. I lived with my grandmother when I was little, and she and I used to recite it every morning.”

Co-creators John Wells and R. Scott Gemmill (also responsible for “ER”) have said that they wanted, in “The Pitt,” to “lean into Wyle’s own Jewish roots…to make Robby’s character come alive.” The reference may even be more specific than that, as members of the Pittsburgh Jewish community have pointed out. One of the victims of the 2018 Tree of Life shooting — Dr. Jerry Rabinowitz—was a Pittsburgh doctor killed when a shooter came into his synagogue, killing 11 congregants. It was the most deadly mass shooting of Jews in the U.S. As one of his patients recalled:

“In the old days for HIV patients in Pittsburgh, Dr. Rabinowitz was the one to go to. Basically before there was effective treatment for fighting HIV itself, he was known in the community for keeping us alive the longest. He often held our hands (without rubber gloves) and always always hugged us as we left his office.”

2.

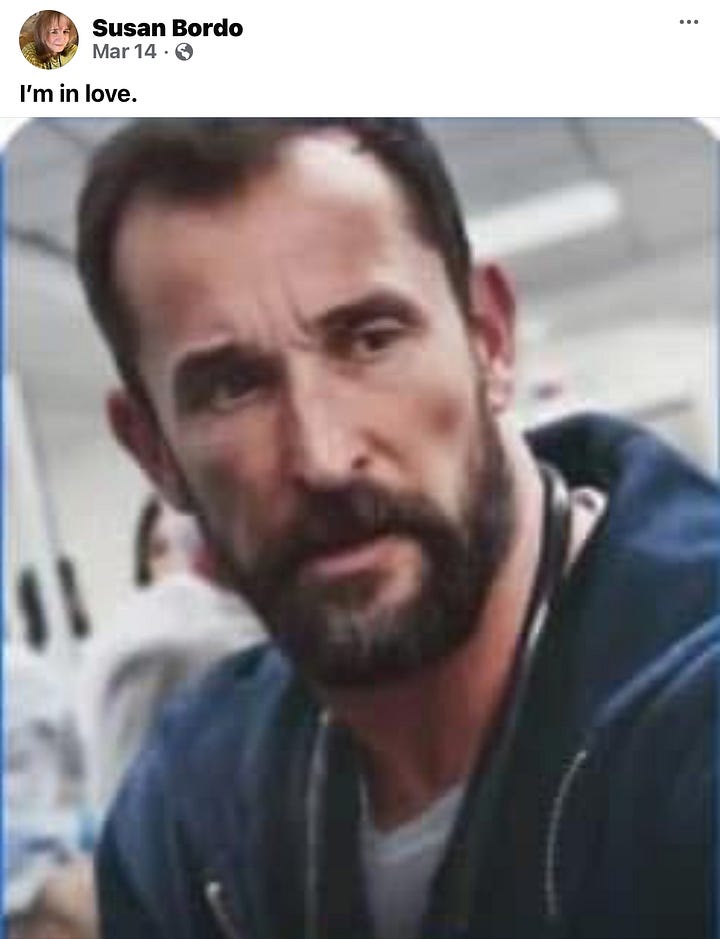

I didn’t realize until “The Pitt” ended that the show apparently has a “rabid,” “obsessed” fan base who enjoy chattering about it on line and have developed “huge crushes” on Dr. Robby: “Not since the early days of another Max show, “Succession,” has a TV program inspired such social media ardor,” reads a New York Times piece. That hasn’t been the case for me. I had a great time during “Succession” speculating about who was going to inherit the business and arguing with the Shiv-haters. But I don’t belong to any fan-groups of “The Pitt” and my online commentary has been limited to two tiny posts. One was right after I saw the first episode—a picture of Noah Wyle as Dr. Robby, with the caption “I’m in love.”

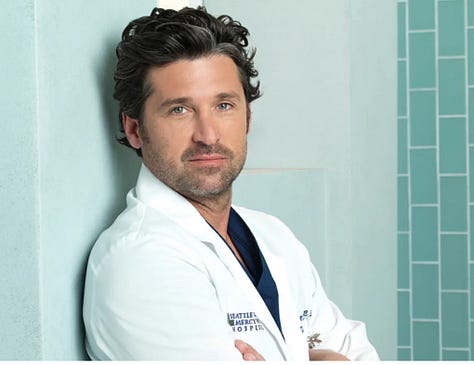

At the time, I thought my admission of love was like announcing my secret discovery of a new continent. As far back as I’ve been watching prime time “doctor shows” on television—that would be as long ago as “Doctor Kildare,” “Marcus Welby, M.D.” and “Ben Casey”— there’s always been a Doctor McDreamy who the female staff swoons over, the patients flirt with, and who sometimes breaks hearts.

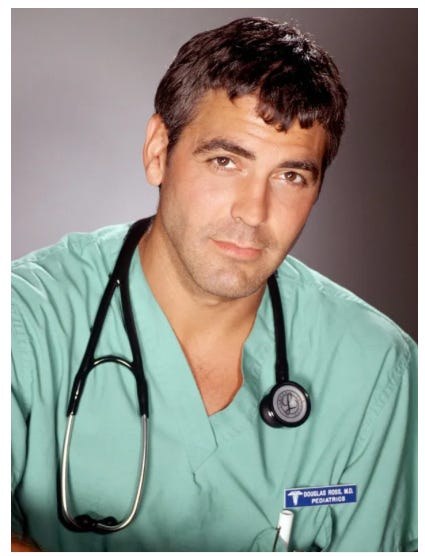

The McDreamies aren’t just good-looking. They are so glamorous that the shows have to make a special point of the fact that they also have medical skills. Unable-to-commit, classic “womanizer” Dr. Doug Ross (George Clooney), who in the pilot episode of “ER” is the cause of a suicide attempt by head nurse Carol Hathaway (Julianna Margulies) turns out to be—of all things—a pediatrician. And just in case we didn’t get the point that he’s not just a sexist dickhead, he diagnoses a battered child while a female intern looks on, surprised and impressed. And later asks if he wants to go “get coffee” with her.

Dr. Robby, with his overgrown beard and weathered skin, doesn’t fit the smooth heartthrob mode. Yet it turns out I wasn’t the only one to fall in love with him. And apparently, it spans generations. The New York Times article investigates this by calling on pop culture critic Cody Corrall, who theorizes something he calls the “babygirlification of tortured adult men,” which he describes as “a fun relationship between young women and young queer people” and “middle-aged men and their traumas and back stories.”

I’m still trying to figure out what Corrall is talking about here. Is it some kind of obscure reference to the movie “Babygirl”? Or is there something about the way Dr. Robby, who has a brief but crushing meltdown after hours of superhuman effort managing a mass-shooting crisis, calls on our protective instincts? Corrall also mentions Kendall Roy (from “Succession”) and “the dudes” from “Severance” and “Conclave” as belonging to this category. Maybe it’s an unbridgeable generation gap, but I don’t feel like cradling any of those guys in my arms and soothing their wounds. (Well, maybe Ralph Fiennes.)

But if I wanted someone to cradle and soothe me, it wouldn’t be Dr. Ross but Dr. Robby who I’d want at my bedside—or better, in my bed. And in 2025, my need for soothing is pretty great. In all the reviews I’ve read I’ve been surprised that none have mentioned how lovely it is, living under an administration that is so indifferent to human pain, to watch a show that takes human suffering so seriously, and in which those in charge lavish so much respect and care on those in need. Doctor Robby is beautiful, not because of superficialities like facial structure and good hair—although Noah Wyle is a handsome man who, in my opinion, has grown much more attractive as he’s aged—but because in every way he’s an antidote to the cruelty and carelessness of those who currently are deciding for us whose life matters, who is worth saving, who is dispensable. You might say he’s an anti-Trump (who has, in contrast to Wyle, grown uglier the older he gets.)

3.

Even in the more limited context of fictional doctors, Robby and his crew are unusually tender. I don’t know how recently any of you have re-watched episodes from other doctor shows, but if you do, you may be shocked at how perfunctorily—sometimes even coldly—those glamorous guys, as well as their colleagues, deal with their patients. Even kindly Dr. Marcus Welby (Robert Young) does a lot of stern lecturing. In one ghastly episode which unfortunately no longer feels like quite the relic it once did, he pressures a woman into having a baby, not just because abortion was illegal then—or even because he considers it immoral—but because he knows best that a baby is a “miracle” that can save her failing marriage. (He also tells her husband about her pregnancy behind her back.)

More recent shows, of course, wouldn’t dare have a doctor telling a woman what to feel about her pregnancy. (In “The Pitt,” Dr. Robby even fudges the gestational age of an 17 year-old’s fetus to keep her abortion within legal limits.) But such specifics aside, before “The Pitt,” humane behavior on the part of fictional doctors usually amounted to: break bad news gently but professionally—and remember you’re not a therapist or a rabbi. Here’s a scene from “ER” In which Dr. Susan Lewis (Sherry Springfield) delivers some news to a patient:

Someone should have taught Dr. Lewis to decide before she entered the room whether that density “could be many things” or it’s the case that “you may not even have six months.” And he thanks her for being “straight” with him! (There’s so much else that’s wrong with the way she treats the situation I could probably write a small essay deconstructing just this scene. But why spend time on the obvious? She isn’t even able to put her hand on his back when he collapses in tears over the prognosis.)

Now here’s Dr. Robby delivering some horrible news. Contrast the gentle timbre of his voice to Susan Lewis’s flat reporting of the possibilities, the empathy written on his face to Lewis’s staring uncertainty in the face of her patient’s emotional reaction. Robby’s hand on the mother’s before he leaves the room. You would think he hadn’t done this hundreds of times before—which he undoubtedly has.

Robby never delivers the news—whatever it may be—and moves on. He’s always circling back, checking in, taking the emotional pulse of people who he knows would rather be any place other than an emergency room. In a more typical hospital series, any one of these ongoing relationships would be presented as unusual, a special bond—perhaps even an over-attachment. In “The Pitt,” though, no one gets chewed out for caring too much.

Is this fantasy-land? All I can say is that every time I’ve posted about or mentioned the series, I’m told by hospital staff that they’ve never seen as realistic a show about life in a big city hospital. Maybe it’s viewers that have gotten the wrong idea—from shows like “Grey’s Anatomy,” whose ongoing story lines center not doctor/patient relationships but on romantic turmoil, heartbreak, and ambivalence. “ER” and “Grey’s Anatomy“ broke ground in all sorts of ways. But let’s face it, the real drama in them—what kept fans coming back week after week—wasn’t as much about the challenges of working in a hospital as in the hook-ups and break-ups happening among the docs.

Not so in “The Pitt.” Crushes and past affairs are alluded to. Victoria Javadi (Shabana Azeez) can’t breathe when Mateo Diaz (Jalen Thomas Brooks) is around (and who can blame her?) And Dr. Robby and senior resident Heather Collins (the mesmerizingly stunning Tracy Ifeachor) have been involved at some point. For exactly how long they were together isn’t clear, but there’s still tension there, and after Collins has a miscarriage, they have a conversation while sitting on the edge of an ambulance that suggests she’d gotten pregnant during her affair with Robby. But this information doesn’t scream loudly of future plot-lines, as is often the case with tv series. Maybe something more will happen between Collins and Robby; it’s just as likely not. It isn’t what the show is about.

You might remember that the first episode of “Grey’s Anatomy” opens with Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) waking up after a night of sex with McDreamy (Patrick Dempsey) who she doesn’t know yet is a doctor at the hospital and with whom she has just enjoyed a night of casual sex). What you probably don’t remember is that during the whole first season the opening credits featured a montage mixing shots of hospital equipment with a babe fixing her eyelashes, red high heels, champagne being poured, the back of a dress (not a hospital gown) being zipped, and legs entwined in a bed, while in the background a soft, femme-y song played. I’ll refresh your memory.

4.

I don’t want to leave the impression that “Grey’s Anatomy” was just another prime time soap opera, located in a hospital. Shonda Rhimes is a genius at making concessions to convention (which, after all, would not be reproduced so often if they weren’t satisfying to viewers) while subverting other expectations. In the case of “Grey” she gave us the first doctor show with a genuinely diverse cast, including a very short Black woman, a full-bodied Latina, and a dour-looking Asian. This may seem like a big yawn now, but Grey broke what until then was the mold: not everyone was drop-dead gorgeous and being non-white was unexceptional. The chief of surgery was a Black male (James Pickens Jr.)—and later, a Black female. The show was narrated by Meredith, whose friendship with another woman, Christina Yang (Sandra Oh, the dour Asian), developed over the course of the first season to be as central, if not more central, than her love life, as they became each other’s “person.” Drawn to each other’s cynicism and intelligence, Meredith and Christina both had romances with gorgeous doctors higher up on the food chain, but neither behaved like salivating nitwits at the sight of the (admittedly unusually good-looking) male staff. I loved it, too, that Miranda Bailey (Chandra Wilson)—the first genuinely ordinary-looking woman to have a top role on network TV—did not slide into the background, as I expected at first, but remained a central character (who got a top job and also got herself a gorgeous man, a departure from the stereotype of the chubby lovelorn woman.

By the second season of Grey I noticed that the tacky opening sequence and song were gone, and gradually, feminist issues began to creep into the plot lines. “Silent After All These Years” follows the aftermath of two rapes: one, a date rape that left Dr. Jo Karev’s (Camilla Ludington) birthmother pregnant, the other a young woman named Abby (Khalilah Joi) who had been violently attacked and raped in an alley by a stranger. Abby is so traumatized that at first she can’t even bear to undergo a rape kit, and is only finally able to do so because of the delicate care that she receives from Jo and Dr. Teddy Altman (Kim Raver.)

The show makes the bold decision to follow the procedure step-by-step, and each photo of her injuries, each swab of DNA, each contact with her bruised body, is orchestrated in the scene as the very opposite of the forced invasion that was the rape. Before each procedure in the protocol (informative in itself; I suspect few people know what a rape kit actually contains), she is asked if she is ready, and a “yes” is required before anything, no matter how minor, is done. It’s a terrific scene, unsparingly revealing her injuries to the viewer, but equally attentive to depicting the tenderness with which Jo and Addison perform each procedure.

Later, in a solution to how to get Abby to the OR for a reparative operation without having to endure any man’s gaze, the women of the hospital—doctors, nurses, orderlies, receptionists—line both sides of the hall she has to travel, so that all she sees are women—their expressions warm, sympathetic, but unstaring, as she is wheeled, slowly and gently toward the elevator.

At a certain point I stopped watching “Grey.” Shonda Rhimes had taken her genius elsewhere after a breakup with ABC (see my review of “Queen Charlotte” for an appreciation of Rhimes.) and the soap opera-in-scrubs became ascendant. That became especially irritating in its treatment of COVID. Showrunner Krista Vernoff had even considered not including the pandemic at all. But she ultimately decided that “to be the biggest medical show and ignore the biggest medical story of the century felt irresponsible to the medical community, it just felt like we had to tell this story. The conversation became: How do we tell this painful and brutal story that has hit our medical community so intensely and permanently changed medicine? And create some escapism? And create romance, comedy and joy and fun?”

They had no problem with the romance. I’m not so sure about the “joy and fun.” As for “telling the story,” the show had the doctors and nurses talking a lot about the misery of COVID, the overwork of hospital staff, about the racism of the system. But “telling,” as all writers and teachers of writing know, can’t hold a candle to “showing.” “New Amsterdam” (an excellent show that was cancelled, as some tv critics argued, because “it may have turned off some viewers looking to escape from real-world medical maladies with fictional ones”) showed more of the pain and brutality Vernoff claimed to want to capture than a whole season of doctors telling each other how awful everything was, while never even looked tired.

And then there was the ongoing plot centerpiece: the near-fatal illness of Meredith Grey. It featured weekly escapes into a dreamy, pastel fantasy of her meeting long-gone friends and lovers on a pure white beach as she struggled between life and death. The trope is gaggingly familiar—during crises she almost joined them, but it “wasn’t time yet” for her, and they helped call her back to life. (If you saw Patrick Dempsey holding her close, you knew the next scene would show her stats plummeting.) And when the other doctors, in a ”last desperate attempt” to get Meredith to wake up after her vent is removed, bring her little daughter Zola to her bedside, of course her eyes open.

How does “The Pitt” deal with COVID? In a sense, everything about the show reminds us of that time and how much we relied on the everyday heroism and fortitude—and care—of doctors, nurses, and staff. The entire first season covers just one day, but it’s a day of nonstop crises that calls on every resource— emotional intelligence as well as medical expertise—the staff can muster in themselves. And unlike “Grey’s,” there’s no getting over it and moving on, particularly for Dr. Robby, whose beloved mentor died of COVID complications on the same date of the day we follow through the 15-week (equals 15 hours of the day) season. Throughout the day, he suffers invasive flashbacks of the moment when he made the decision to withdraw life-support—something he’s haunted by, wondering if he could have done more—while those who know and love him take note of his shorter-than-usual temper and momentary driftings. And then, after his stepson lashes out at him for not saving his girlfriend, he ushers him out the door and breaks down in well-earned sobs.

“That breakdown scene was why I wanted to do the show,” Noah Wyle has said. “I wanted to make a show about a health practitioner that we invest a tremendous amount of trust and belief and admiration in. And when the shit hits the fan, we are expecting that white knight to come charging in on his horse. Then the horse comes in without its rider, and we don’t know where the hero is, and it’s because …”

His voice breaks. “He’s on the floor,” he says, dropping to a whisper. “He’s on the floor. And how do we get off the floor? How do we admit the fact that we break? How do we rebuild?”

I love that for Dr. Robby being Jewish just is part of who he is. He’s a great doctor and so very human. It’s nice to see Jews portrayed so positively for a change. I’ve noticed for quite some time most Jewish characters were either the obnoxious female you don’t want anywhere near your life or the deadly former Mossad agent turned evil pariah.

Yes Dr. Robby is sexy, too. Strong, intelligent men can and should be vulnerable too. It’s really simply called being human.

Same take for me on all counts - well expressed as usual!