From Kentucky: A Howl in Four Parts

I want every legislator in my state to be strapped onto an examination table, legs in stirrups, eyelids propped open, forced to watch “Happening.”

When did it all begin?

Perhaps a long, long time ago, in some smokey room behind a church—or the staid living room of a wealthy plantation owner—or a secret meeting of the men of the town council—or a tavern of men, drink loosening their anger—or the troubled brain of one man—or a thousand—sleeping next to their wives.

Ironic, when you think about it, that the babies we had—babies of slaves, babies of immigrants, babies of depressed middle-class housewives, babies both desired and others forced into the world—babies that God and Nature had declared were women’s role to produce—would cause so much trouble?

No matter. That word ”equality”—a calm abstraction created by fevered men whose beliefs trailed behind their eloquent words, their desire to make revolution—could always be nullified. You just had to be crafty, covert, exploiting all opportunities. You could count on the lulling deceptions of “progress.” You could count on the unwitting (and sometimes not unwitting) collusion of the sellers, the headline-makers, the too-busy-ness of ordinary people working their jobs, the niceness of your political opponents.

And when the most promising opportunity emerged—in the figure of a demonic idiot/genius who knew the magic words—“You don’t have to take this any more”—you made him your president.

How convenient that the woman he ran against was everything you despised, how delicious it was to turn her into a witch. How willingly, how eagerly the politicians and the newspapers and the social media helped you along! How useful that they all now seem to have forgotten that she predicted everything that has happened.

All it took was four years for them to finally consolidate their power.

In 2012, the mainstream media had been on high alert to threats to reproductive freedom. They hailed Georgetown law student Sandra Fluke as a heroine when she testified in congress in favor of a federal mandate requiring religiously affiliated institutions (such as universities and hospitals) to offer cover for contraceptives to employees. When Rush Limbaugh called her a “slut” and a “prostitute” who is “having so much sex she can’t afford the contraception,” his remarks set off a firestorm of support for Fluke, and he was eventually forced to apologize for his “insulting word choices.”

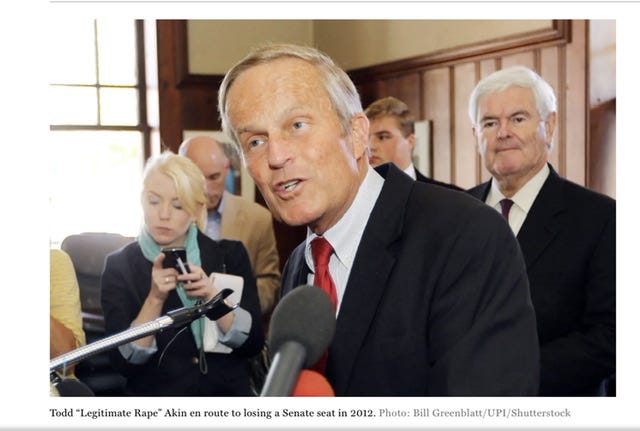

In August, Representative Tod Aikin, senate nominee from Missouri, arguing against exceptions for rape victims, said that in instances of “legitimate rape,” women rarely get pregnant: “The female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down.” He is berated in the press and defeated in the election.

In October, Senate candidate from Indiana Richard Mourdock says during a debate that “Life is a gift from God. And, I think, even in the situation of rape, that it is something that God intended to happen.” He, too, is eviscerated by the press, and defeated in the election.

The same month, Vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan gives an interview in which, defending his position that there should be no excuses for abortion, refers to rape as a “method of conception.” He is forced to explain that he wasn’t advocating rape as a fertility aid.

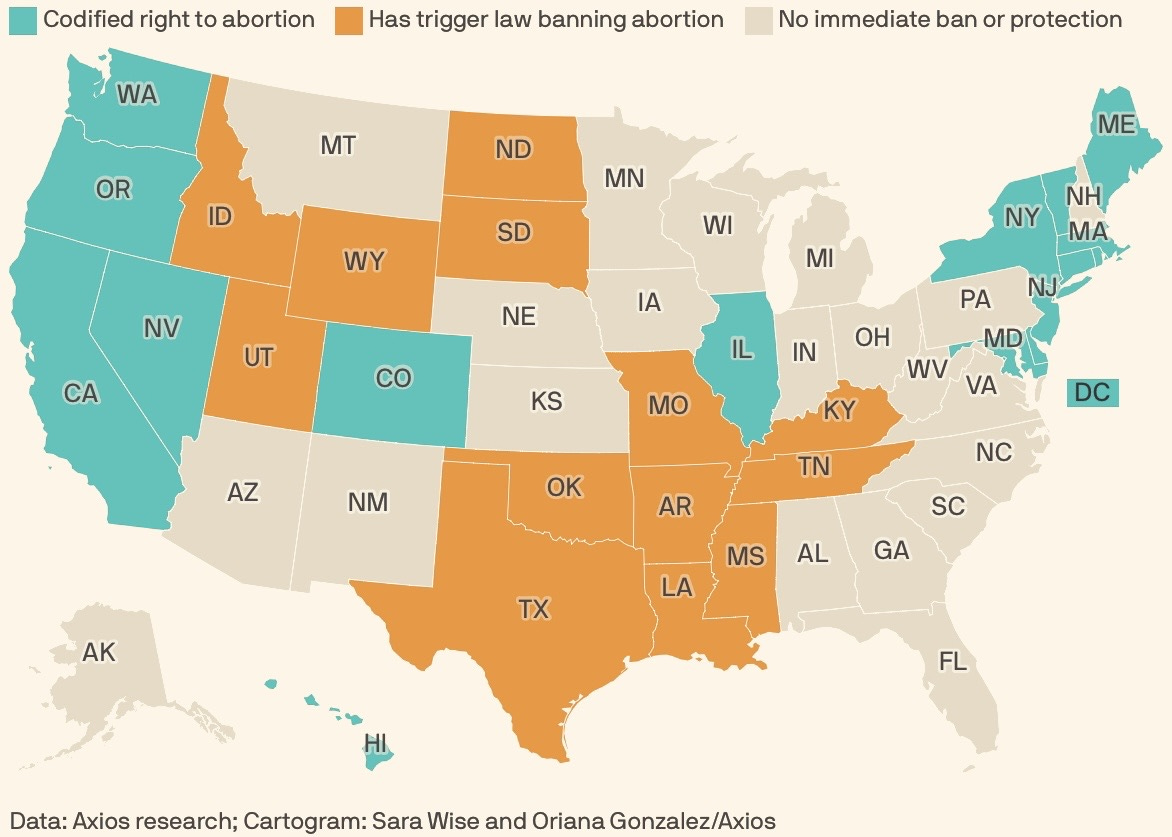

None of the media outrage or lost elections caused conservative republicans to quit their efforts to institute state control over women’s bodies. Throughout 2014, conservative legislatures in many states passed a slew of restrictions aimed at making abortion inaccessible even if still technically legal under Roe vs. Wade.

But no one seemed to be paying attention any more in 2016.

Vice-Presidential candidate Mike Pence’s career militating against Planned Parenthood and federal funding for pregnant victims of rape barely rated a mention in the papers or political news shows. Nor did his 2014 bill, requiring that all women seeking an abortion have an ultrasound 18 hours before the procedure.

As for Trump, when MSNBC host Chris Matthews pressured him to give a yes or no answer to the question of whether women who have abortions should be punished, he waffles for a bit, then replies “yes.” When, after the election, “Sixty Minutes”’ Leslie Stahl questioned him about the consequences of a repeal of Roe v. Wade, he waved aside the issue of the effects on women living in states that would outlaw legal abortions: “They’ll have to go to another state” he shrugs.

In 2012, the notion that women who get abortions should be punished or Pence’s proposal for fetal funerals would have ranked, along with Aikin’s and Mourdock’s remarks, as monumentally misogynist mistakes, politically speaking. In 2016, they slid off the candidates into a growing heap of “gaffes” which the press largely ignored, preferring to raise alarms about Hillary Clinton’s emails.

It wasn’t just the Republicans. When Bernie Sanders described Planned Parenthood and NARAL as “establishment” and abortion as a “social issue” (as though loss of control over ones reproductive life had no impact on ones economic survival), the mainstream media sounded no alarms. Sanders regarded “our” issues as peripheral disturbances to getting out the “real” message of economic inequality. In an interview with Rachel Maddow, he described the fight for reproductive rights as a distraction from “serious issues.” That hadn’t much changed by 2017 when he supported anti-choice Nebraska mayoral candidate Heath Mello, arguing that “you just can’t exclude people who disagree with us on one issue.” One issue?

On “Happening”

So now, in 2023, we have to do it all over again. Except this time, feminist generations no longer seem as divided as they were in 2016. And symbolic coat-hangers on signs demanding “choice” are no longer enough. This isn’t about choosing which pair of jeans to wear. And it isn’t “one issue,” but has impact on every aspect of women’s lives. We’re talking about justice and equality, and are unwilling to spend a whole lot of time defending ourselves against the notion that we are “pro-abortion.”

Still, what women’s lives will be like if we don’t win this war remains an abstraction for those who have yet to experience first-hand the deprivation of reproductive freedom and access. The urgency of turning the “issue” into un-euphemistic concreteness is what compelled Annie Ernaux to write about her own experience in the early sixties, when abortion was illegal in France (and the United States.) She produced a harrowing memoir, which has since been made into a gripping film which is almost as harrowing. In one scene, we watch as Annie inserts a knitting needle into her vagina, trying to induce an abortion herself, having been unable to find a doctor who would help. (Actually, “not helping” is putting it mildly; one prescribes something that she thinks will bring on her period, but turns out to have been the opposite: a preventative to miscarriage) Later, after finding a doctor who is willing to insert abortion-inducing probes, she does finally succeed in terminating her pregnancy—and almost dies afterward. She also has to endure the horror of watching the dead fetus drop from her body. A friend (called “O” in the book) cuts the chord. From the book:

We don’t know what to do with the foetus. O goes to her room to fetch an empty melba toast wrapper and I slip it inside. I walk to the bathroom with the bag. It feels like a stone inside. I turn the bag upside down above the bowl. I pull the chain….

… I was losing blood. At first I didn’t take any notice, I was certain everything was over. Blood was gushing from the severed cord in spurts. I lay motionless on the bed; O kept handing me towels that soaked up the blood in no time…. I tried to stand up and saw stars; I thought I was going to die of a hemorrhage. I screamed at O that I needed a doctor immediately. She went downstairs to wake up the janitor but there was no answer. Then I heard voices. I was convinced that I had already lost far too much blood. The arrival of the doctor on night duty heralded the second part of the night. Sheer experience of life and death gave way to exposure and judgement. He sat down on my bed and grabbed my chin: “Why did you do it? How did you do it? Answer me!” His glaring eyes bore into me. I begged him not to let me die. “Look at me! Promise me you’ll never do it again! Never!” Because of his wild expression, I believed he might actually let me die if I didn’t promise.”

The book spares us nothing. And the film is only marginally less excruciating in its details. Because it is visually enacted, the impulse to turn away, especially from the scenes I’ve described, is strong. But turning away is exactly what Ernaux does not want us to do. The act of writing about her experience is precisely to make us look:

“I realize [my] account may exasperate or repel some readers; it may also be branded as distasteful. I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled. There is no such thing as a lesser truth. Moreover, if I failed to go through with this undertaking [SB: writing the book], I would be guilty of silencing the lives of women and condoning a world governed by male supremacy.”

I want every legislator in Kentucky and every other “red” state to be strapped onto an examination table, legs in stirrups, eyelids propped open, forced to watch Happening.

Meta “choice” and “personhood”

This is not a struggle between those who value “life” and those who want to give women “choice.” “Choice” became our brand defensively, as we insisted, against those who would portray us as casually scraping embryos out of our bodies, that we were not “pro-abortion.” But those who want to deny us reproductive freedom, those who want to jail or execute us if we exercise that freedom, they are in favor of “choice,” too. They just want to make the choice themselves rather than the girls and women most affected. And with that insistence they deprive us, not only of “choice” over our reproductive lives and all that entails for our ability to care for ourselves, our families, and future generations, but of our full equality under the law.

This isn’t about whether the fetus is a “person” but whether a pregnant woman is a “person.” Fetuses are virtually “super-persons” who have rights that supersede not just the rights of their mothers, but are more extensive than those granted to anyone else in our society. Who else besides the fetus can make a claim on another person’s body to operate as a life-support system for them? Our legal system values bodily autonomy so highly that no one has ever been forced to take a simple blood test—even when the life of another hangs in the balance. Yet centuries of ideology and legal decisions have nullified bodily autonomy—and in the most invasive ways—when it comes to pregnant women, centuries that have seen our proper role as that of fetal incubator rather than human subject. No, it’s not the fetus whose “personhood” is at issue; it’s women’s.

The denial of reproductive freedom is existential as well as political. It’s political in that it turns women into less-than-equal subjects under the law. It’s existential not only in the fact that it deprives us of “choice” but turns the pregnant body into a numb and mute fetal delivery system, without human subjectivity, a provider of baby “stock.”

I’m always surprised to see pictures of Samuel Alito. He’s actually a few years younger than I—another Boomer, but of the right-wing backlash variety—but in my mind he is ancient, a relic who quotes, in Dobbs, from a seventeenth-century ideologue who uses religious tracts to justify his position on abortion. More surprising—as she has been pregnant herself—is Amy Coney Barrett. When she was pregnant, did she regard her own body as little more than protective padding and nourishment for a fetus? Or did she expect those who loved her to be tolerant and caring of changing moods and anxieties? Perhaps pregnancy didn’t affect her at all, perhaps she simply embraced the experience of being a fetal incubator.

I doubt it.