The dead are dead,” Liz Danvers (Jodi Foster) insists. “There’s nothing except us. We’re here, Navarro—alone. The dead are fucking gone.”

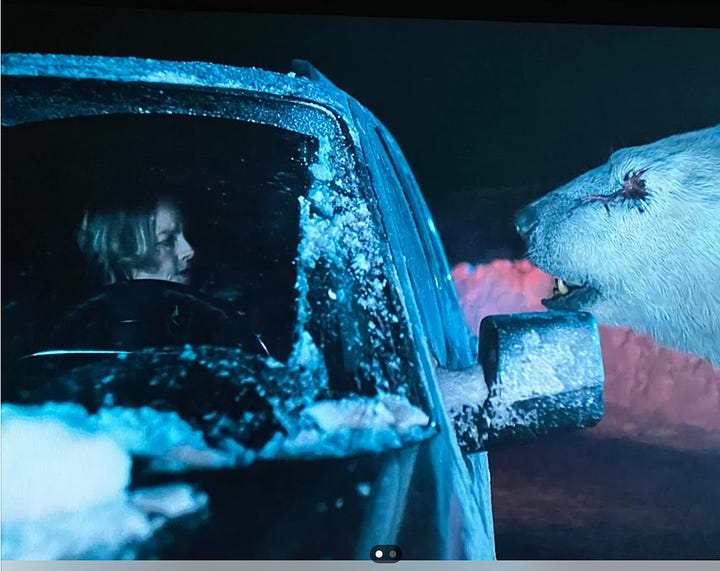

Except at that moment, Danvers is proving herself wrong, as she throws Holden’s toy polar-bear out the door, trying to convince Navarro—and herself—that she means what she says. But it isn’t that easy to banish the dead. Earlier, a drunken Liz had plowed her car into a snow drift, trying to avoid hitting a huge, white, one-eyed polar bear. The bear stares her down through the window, then lumbers off.

Is the bear real, a ghost, or a hallucination in which the peek-a-book game Danvers had played with the toy bear and her son Holden has come to haunt her?

That’s asking the wrong question.

The right question is: “Why would anyone expect to be able to simply throw grief away?” It never works. You can throw the toy away. You can incite a bunch of thugs to beat you up in an effort to make your physical pain more real than the numb absence you (don’t) feel. You can become a hard-ass who prides herself on not caring. You can plunge into your work, obsessively, recklessly. You can fuck and fuck and fuck. Everyone in town, the harder the better.

You can turn your eyes away whenever you accidentally come across a piece of paper with your sister’s handwriting on it—elegant, old-school slanted, imprinted by the training of another era. But then, you’ll find her underwear mixed with your own, left from a visit, and there she is, sitting on the couch across from you, stroking your foot. Or, for no reason at all, you decide to cook hard-boiled eggs the way she did (get the water to boil; put the eggs in, cover and turn the heat off) and all day long she follows you around.

Whatever you do, the dead will show up anyway.

When Rose Aguineau comes to the door all Christmas-Eve dazzling, in a body-hugging dress, her hair styled, it’s kind of a shock. As an actress, Fiona Shaw has been a shape-shifter. But the character of Rose, up until then, has been a reclusive weirdo, a bag-lady in a brown-hooded parka who sees dead people and has ideas about why they come to us.1 What’s with this red satin dress?

It’s for Evangeline Navarro (Kali Reis, with a face so tough/tender it can melt heart-ice.) The two are spending Christmas Eve together, and Rose tells Navarro that before she was an old, crazy lady she was “a very serious professor in a very serious school, writing very serious ideas.” Then, “one Tuesday morning after coffee, I sat down to polish some pompous, useless article. And I just had enough. I had enough. Every damned word I'd written in my entire life was meaningless. Making so much noise. So much noise. It is a little quieter here. Mostly. Except for all the fսckin’ dead.”

The episode is dark, very dark. But Showrunner Issa Lopez, on the “Night Country” podcast, can also joke about it. It’s “the most fucked up Christmas special ever made in the history of television.” Yes, that is true. (I won’t go into detail, for fear of “spoilers.”) And it’s also true that if you’re looking for narrative clarity or believability, you won’t find it in “Night Country.” Lopez has said that she wrote it with “the idea of sitting down around the fire, and [let’s] have some fun and have some feelings and have some thoughts. And anybody that wants to join is welcome.”

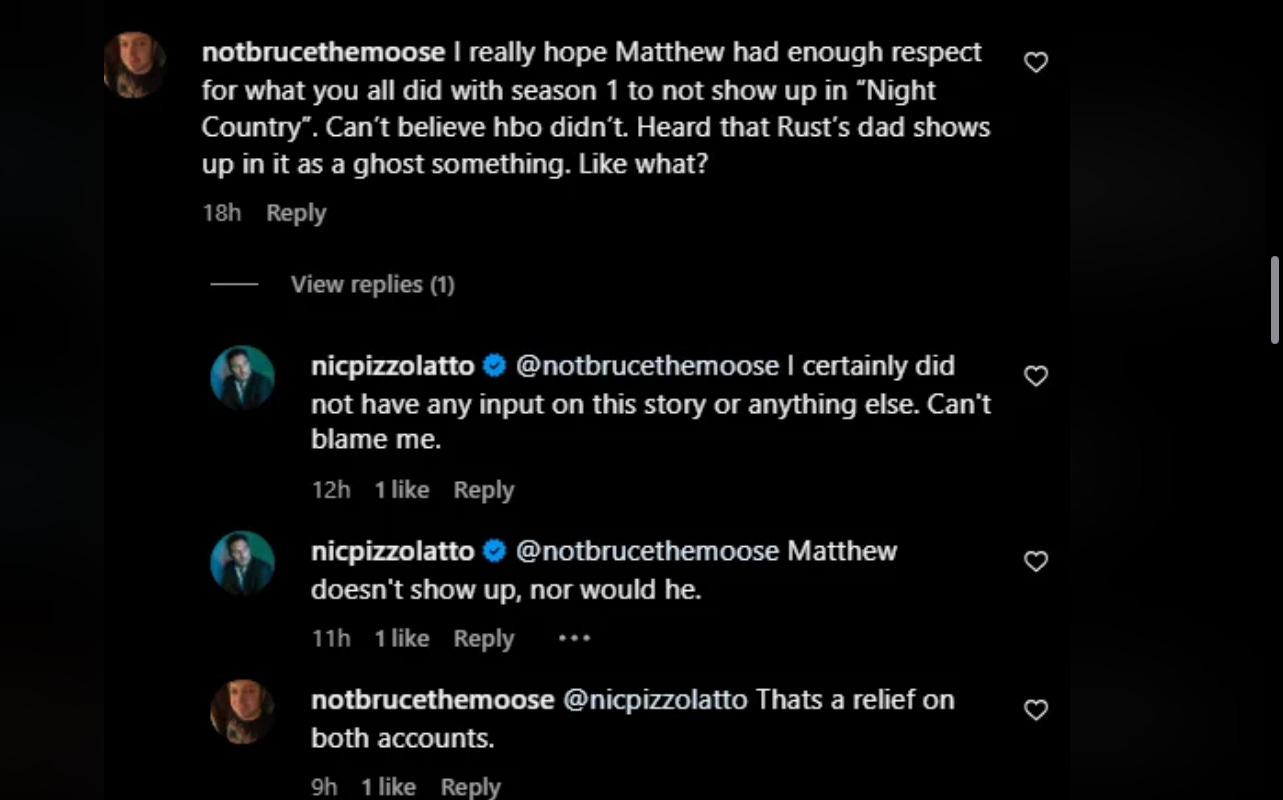

“Some thoughts and some feelings.” Around the fire. Kind of cozy, share-y, girlfriend-y, not exactly the approach of the first season of “True Detective,” and Nic Pizzolatto, who created and was show runner for the first three seasons made his scorn clear on TicToc:

“Can’t blame me.” And don’t worry, Matthew (McConaughey) would never show up. And Pizzolatto’s bro breathes a sigh of relief.

Not surprisingly, a lot of hardcore fans of the first season were happy to have Pizzolatto disown season 4. Their loss. I love the new season, and what happens when you trade (up) existential macho and naked babes for all women in hooded parkas with past lives. Now, I also loved Season one—every bit of it the first time around, irritated by all the pretentious malespeak the second time around, but ultimately loving it again after Rust and Marty (Woody Harrelson) reunite in episode 7. Call me a girl, but in the end it was the evolving relationship between Rust and Marty that made the series more than just an extremely well-made thriller. And despite Pizzolato’s attempts to detach season 1 and 4 from each other, it’s the two women detectives—not the many clever cross references and shared symbols (the not-so-hidden “easter eggs”)—that, like Rust and Marty, make the series compelling.

Like Rust and Marty, Danvers and Navarro are an oil-and-water team. They have different philosophies of life—both Marty and Liz don’t go for anything they can’t see or touch, while Rust and Navarro are tempted by the metaphysical. There’s also betrayal and deep alienation between them. But while Rust and Marty break with each other because of events that take place during the season, the hostility between Danvers and Navarro is the result of a past event (which is only just beginning to be clarified in this episode.) I’m pretty sure that, like Rust and Marty, going through the dark tunnel of the season—much darker in “Night Country,” both literally and figuratively—is going to change things. Will they become BFF’s? I’d be surprised at that. But already, the ice is melting. A shared laugh about Danvers’ attempt to pronounce an Inupiaq phrase. A touch on the shoulder here and there.

The plot and genre are all over the place, and the season is, in many ways, a hot (cold) mess. But to hell with figuring stuff out. Just savor Kali Reis and Jodie Foster. Reis, a former star boxer, walks like it, and as Navarro is the embodiment of what “butch” used to mean (I don’t know if it means anything anymore): a fierce, undaunted protector, but in the service of the tenderest of feelings. Contained, watchful, wise about when to listen and when to challenge, when she smiles, those two studs create dimples that that make you want to pinch her cheeks, and you love that she’s smiling—even better if she’s laughing—because it’s so unexpected and winning. So lovable.

But so is Danvers, even though she’s selfish and bossy, and unlike Navarro, largely oblivious to the needs of everyone around her. She’s still lovable—not just because we know she’s lost a child she adored and is afraid to feel anything that opens her up to hurt, but because she’s so clueless and unperceptive. Like a little kid in a permanent sulk who careens from one mess of trouble to another. She has no patience for her stepdaughter Leah’s (Isabella Star) exploration of her Inupiaq heritage; it’s out of fear for her, but Danvers handles it so poorly that she drives Leah out of the house. At which point, well what the fuck, she’ll just get drunk and then drive across town for rough sex with Ted Connolly (Christopher Eggleston—are you kidding me? But giving her a sexier fuck-buddy, like Navarro has, would have been all wrong. And anyway, as Navarro notes, there’s probably no one in town Danvers hasn’t slept with. She’s oblivious to the aesthetics of date-choice.)

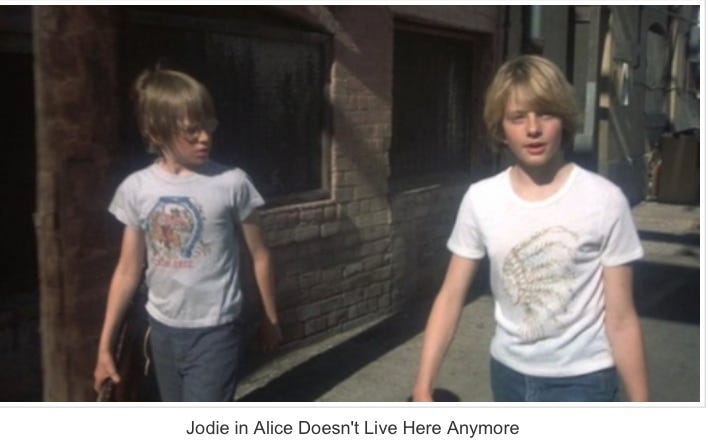

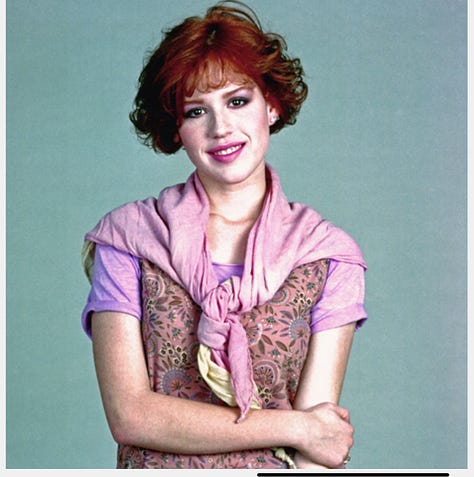

It’s a cliche, but this role was made for Jodie Foster. I guess, though, it would be more accurate to say that Jodie Foster made the role for herself. Initially, she loved the script, but felt it wasn’t written “for someone my age, and I felt like there are some changes that happen at that age that needed to be addressed.” I love that “for a woman my age.” And bless her, Jodie isn’t afraid to look it either. At the same time, she looks more than ever like she did when she played the scrappy kid in “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.”

Foster wasn’t drawn to Lopez’s original concept of Danvers, which was more familiar and conventionally sympathetic—a woman on the verge of breaking down who finds her strength. The way they “bridged their creative gap” was by making Danvers “an asshole.” Jodie loved that “mission,” and so did Lopez: “I thought about all the prestige TV and all the male antiheroes who are so iconic—the Walter Whites, the Tony Sopranos, and I was like, why don’t we have a bad bitch?”

She’s not all that bad. But bad enough to be interesting.

Despite López’s invitation to sit around the fire and have some “fun,” don’t expect much of that in “Night Country.” I think I laughed out loud once, when Hank Prior accuses Danvers of playing Mrs. Robinson with his son Pete (Finn Bennett) and Pete asks “Who’s Mrs. Robinson?” So I did appreciate Lopez’s wry comment about episode four being “the most fucked up Christmas special ever.” All week, I’d been feeling haunted by ghosts myself. My husband Edward has to have an operation on a torn tendon on Thursday, and a jumble of dark and anxious feelings had settled over me, reminding me that hospitals were places where my father, mother, older sister, had died. The deaths were all unexpected, and so was my active, sturdy husband’s leukemia eight years ago. While I gave myself over to visiting him in the hospital, then disinfecting the house, cooking in the prescribed ways to eliminate any bacterial problems, I marched on, doing what had to be done. And he recovered. But my body had learned what dread and what the abandonment of normalcy to care for the sick feels like, and back it’s all come rushing, dragging with it the feelings I had during my sister’s illness and death. It’s just a torn tendon, I tell myself. But it has brought back the ghosts.

Eventually, after listening to the podcast, I did fall asleep. And woke up with the title of this piece in my head.

It seemed right for “Feud: Capote V. The Swans,” too. For that show is also full of ghosts. The most obvious is the appearance of Truman Capote’s mother, played by Jessica Lange, who stirred my cinematic subconscious, whispering seductively to Truman about death, luring him to be with her. She was an angel of death once before, in “All That Jazz.” Then, she was luminously gorgeous, now (fine-tuned by years playing a variety of roles on “American Horror Story”) she is wonderfully witchy, unabashed about the dry desert of lines, the sharpness of her bones, purring in his ear. It’s a great “cross-textual” moment, calling up not just Truman’s dead mother, but a ghost from our movie past. And Roy Scheider also now dead. And Bob Fosse, too.

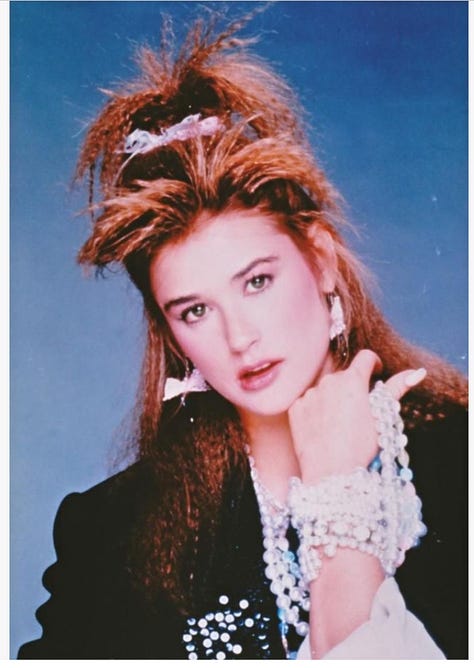

Not all ghosts are dead people, though. Lange’s unexpected appearance made me think about all the other actresses’s younger lives. We’ve known several of them as far back as their adolescence, and those past identities endow the roles they play with the reality of the passage of time.

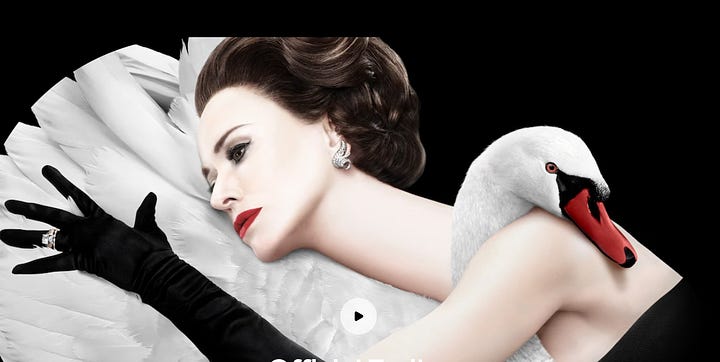

Ryan Murphy, the series creator and showrunner, wanted that resonance. “I wanted icons to play icons,” he’s said. “Women who were iconic and had some degree of fame and success would understand what it was like to be Swans. I thought they would know the gravity and also the stress of being a star.” These actresses, who made their names in the 1990’s, would understand from the inside “the scrutiny of the press and how people would write about literally how much women weighed. It was very moving to see this group of women who had survived that. Survived and thrived.”

Not all survived in the same way, though. For women, especially if they have been beautiful works of “art” (as Truman Capote believed the most perfect of his feminine swans—Babe Paley—to be) the passage of time comes with a choice. Do we try to preserve the illusion of agelessness, as some of these actresses apparently have, or do they become (as Barbie puts it, in Greta Gerwig’s film) someone who “makes meaning rather than being the thing that is made.” Jodie Foster and Jessica Lange (and Helen Mirren, Glen Close, Meryl Streep, Diane Keaton).have relished the freedom and sturdiness of that alternative. And in “Feud,” the performances that are the most haunting are those that allow the bodies to show the years. It’s not just about surgery or Botox; it’s about the willingness to project gravitas, resentment, regret. Calista Flockhart, playing Lee Radziwill, is as irritatingly pouty as she was as Ally McBeal, but Naomi Watts, with that that little downward drag on her mouth that gives away not just age but sorrow, is exquisite—and bruised. Which the real Babe, for all her wealth and prestige, was. Badly. By years of humiliating abuse by her husband, and then betrayal by Truman.

Rarely are actresses so perfectly incarnate in their roles: Besides Watts, there’s Diane Lane as the elegant Slim Keith—a “man’s woman” who takes no guff, like Howard Hawk’s (her first husband) famous screen babes. Chloe Sevigny as C.Z. Guest, the most avant-garde, accomplished, and forgiving of the swans. And Demi Moore as Ann Woodward, whose likely murder of her husband Truman turned into a dinner time amusement. (The dialogue in the film in which he describes the murder comes straight from “La Cote Basque,” the publication that “splayed” Babe, Slim, and Anne’s secrets all over Esquire.) As Anne, Demi has grown into and embraced the cut-you-with her-face coldness that was lurking behind her baby-face in earlier roles. (Being really skinny helps.) Molly Ringwald (playing Joanne Carson, ex-wife of Johnny) and Callista Flockhart have yet to come to life for me. But the narrative is fashionably time-hopping, and they will probably be around more in future episodes.

Although the season is “based on” Capote’s Women, so far, in keeping with the series, it’s focused on Truman’s “feud” with the swans, which in the book only takes up the last two chapters. In doing research for this piece, I read that book, as well as “La Cote Basque,” and was surprised to find both how lousy “La Cote Basque” is as a piece of writing—hardly worth sacrificing the trust of friends for—and how nasty Capote’s Women is. In the book, as in “Basque,” the women appear as soul-less, serial husband-hoppers and what we nowadays call “influencers.” The author, Laurence Leaner, makes comparisons between the constraints on women during the pre-feminist 1950’s and Edith Wharton’s gilded age, but his descriptions emphasize female scheming and superficiality, and no apparent recognition that beneath the pursuit of a rich husband there just might have been yearnings of another sort: “She appraised men the way a gemologist evaluated diamonds, making a close examination to determine their precise worth”; “She had pursued the life she wanted with calculation and savvy”; “Looking at Stas, Lee checked off every attribute she sought in a man.” At one point, he even seems to blame Babe for Bill Paley’s neglect of her: “By being endlessly solicitous to her husband’s every want, Babe helped to create a monster of self-regard.” There are no “receipts” given for these assessments; they are Leamer’s take-aways.

Truman Capote’s feelings about women were more complicated. He loved the world of the women he ultimately betrayed—he saw their attention to the details of their own appearance, their table-settings, their observance of detail, as a form of artistry. And he loved being with women, who cherished their intimacy with him—unlike men, whose potency was sexually compelling but for that same reason, indelicate, without art. “La Cote Basque,” in my opinion, was not written out of jealousy, revenge, or suppressed misogyny, but his own exalted and increasingly desperate, self-deluded sense that the writer is a god for whom all is permitted in the service of his art. He was genuinely shocked when his women friends didn’t get that. When they stopped answering his calls, as Joanne Carson (not a New York swan herself, but a new-age-infatuated Californian whose friendship became more important when the others rejected him) relates, “he looked like a baby who had been slapped,” and went into the guest bedroom, rereading and obsessing over the passages that had offended Babe and Slim.

Truman’s actual love of women, so apparent in “Breakfast at Tiffanys” and so cruelly squandered in “La Cote Basque,” made me think of Holly Golightly as another kind of ghost that haunts both “Basque” and “Feud.” Truman told Playboy in 1968 that “The main reason I wrote about Holly, outside of the fact that I liked her so much, was that she was such a symbol of all these girls who come to New York and spin in the sun for a moment like May flies and then disappear. I wanted to rescue one girl from that anonymity and preserve her for posterity.”2

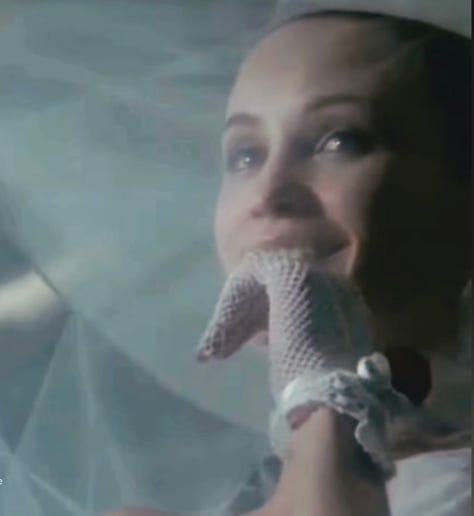

He succeeded at that, because despite the fact that at the end of the novel, Holly goes off in pursuit of a rich man (“Do me a favor, darling. Call up the Times, or whatever you call, and get a list of the fifty richest men in Brazil. I’m not kidding. The fifty richest: regardless of race or color”) but because the free-spirited life she leads throughout the novel struck a chord with us sixties girls. And then, too, there was the movie, in which Audrey Hepburn offered our identification with Holly a visual embodiment to aspire to. Neither a caged swan or a June Cleaver, but a new kind of feminine icon: non-domestic, sexually adventurous, with a body that declared the “mammary madness” of the fifties was over.

That wasn’t what Truman’s swans aspired to; they were of an age and class that still believed a woman was nothing without a man (Hollywood, apparently, still believed that too, and gave Holly a Prince Charming—played by George Peppard—at the end of the movie). But that doesn’t mean they were nothing without their marriages, their dinner-parties, the jewelry their husbands gave them in payment for their extra-marital affairs. Both “La Cote Basque” and Truman’s Women want to banish from their female characters the ghost of Holly Golightly, who taxis to Tiffany’s when she needs to get over the “mean reds”: “It calms me down right away, the quietness and the proud look of it; nothing very bad could happen to you there, not with those kind men in their nice suits, and that lovely smell of silver and alligator wallets. If I could find a real-life place that made me feel like Tiffany’s, then I’d buy some furniture and give the cat a name.”

Holly can still be glimpsed, though, in Ryan Murphy and Gus Van Sant’s more empathic, woman-centered view than either “Basque” or Capote’s Women. Of course, the swans are still depicted as dedicated to the “art” of upper-crust femininity. But Murphy and writer John Robin Baitz chooses to emphasize, as well, their warm girl-bonding and fidelity to each other. “I don’t know what I’d do without these lunches,” Babe says—and it’s not because of the exquisitely prepared souflee. Like Truman, the women need the intimacy of girlworld. When Babe is in bed, sorting her jewelry, anticipating her death from cancer, Slim crawls in beside her and they snuggle. It’s not a scene that’s in either “La Cote Basque” or Capote’s Women.

Many male reviewers didn’t get it. Mike Hale, in The New York Times: “This could be the framework for gossipy, sexy, stylish, tragic entertainment, but that does not appear to be what the show’s creators — who include the writer Jon Robin Baitz; Gus Van Sant, who directed six episodes; and the executive producer Ryan Murphy — had in mind. They have gone instead for chilly, moralistic and cautionary. ‘Capote vs. the Swans’ feels as forbidding and vindictive as the society wives who pass judgment on Capote….lacquered gorgons (for whom the show occasionally sheds crocodile tears, as in the case of Paley’s cancer diagnosis.)”

Lacquered gorgons? Crocodile tears?

Betsy Reid of The Guardian, sees it differently: “One would assume from both the set-up and marketing of the second season that things would be even cattier this time around, Feud: Capote vs the Swans sold with doctored images of glamorous actors, from Diane Lane to Demi Moore, underlined with the tagline “The Original Housewives”. And while we do get a lot of the bitchiness we expect, spewed by finely coiffed women holding coupe glasses, we also get the poignancy we don’t, the series a rather sad, and surprisingly sensitive, look at the wine-soaked misery behind the baity headlines….

….There’s grief not just for the end of a friendship but also of an era, what happens to those at the party when the lights come up….By choosing to highlight melancholy over meanness, the second Feud burns far brighter then the first.”

Poignancy, sadness, grief, melancholy over meanness. It’s not just for the swans, but the Truman Capote who was in love with Holly Golightly, who adored his women-friends, who wasn’t yet fearful (though he bragged otherwise) that he no longer had it in him for a sensational new splash of a book and instead had to turn to plundering the lives of the women he needed much more than he realized.

In episode 1, Rose tells Navarro: “The thing about the dead, some come because they miss you; some come because they need to tell you something you need to hear; some of them just want to take you with them. You need to know the difference.”

Capote’s Women, p. 199.

I've been in and out of _True Detective_ over the seasons, but this season pulled me in from episode one; and it's been a stop-whatever-we're-doing-and-focus kind of show. My spouse and I also end up unpacking it for days afterward. When Rose admitted that she had been a professor, both of us (my spouse is also a former professor) gasped ... yet neither of us was surprised. That little subplot of how she's navigating life post-academia, to me at least, acts as a kind of microcosm of the larger narrative of how all of us are handling our respective "dead" and their related (or not related) ghosts. The entire "long night" frame is perfect for this as well. As an audience, we have no frame of reference for what time it actually is in the fictional town of Ennis. It's as if the entire town is being pulled along through the underworld, rather than the underworld coming to them.

I appreciate your deep dive into both these shows. I'm loving them so much, for all the reasons you outlined. A great read, thank you.