How Courtly Love Betrayed Anne Boleyn

The anniversary of her execution is coming up, and in commemoration I’ll be posting excerpts from my book, including interviews with Genevieve Bujold, Natalie Dormer, Hilary Mantel and others.

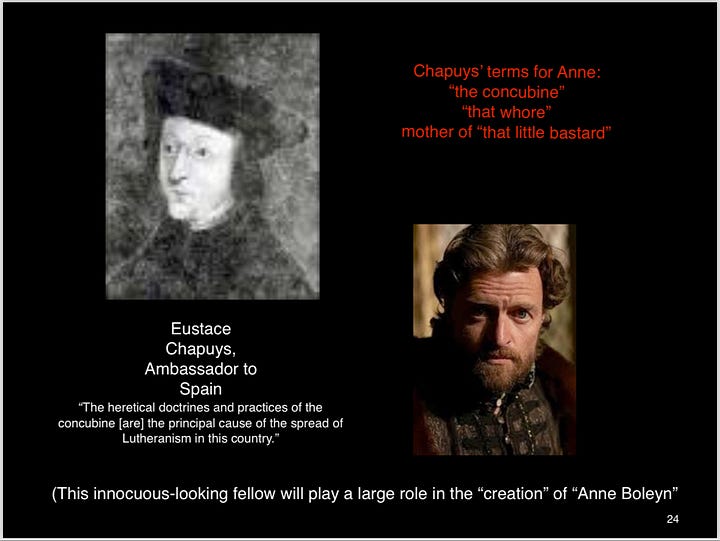

There are a number of theories as to what allowed the unthinkable—the state-ordered execution of a Queen—to happen. One theory, first advanced by Retha Warnicke and adopted by a number of novels and media depictions, is that the miscarried fetus was grossly deformed, which led to suspicions of witchcraft. But although Henry complained, at one point, that he had been bewitched by Anne, that was a notion that, as in our own time, was freely bandied about in very loose, metaphorical manner. It could mean simply “overcome beyond rationality by her charms” (as Chapuys means it when early in Anne and Henry’s relationship, he complained that the “accursed Lady has so enchanted and bewitched him that he will not dare to do anything against her will.”[1]) Moreover, none of the charges later leveled against Anne involved witchcraft, and there is no evidence that the fetus was deformed.

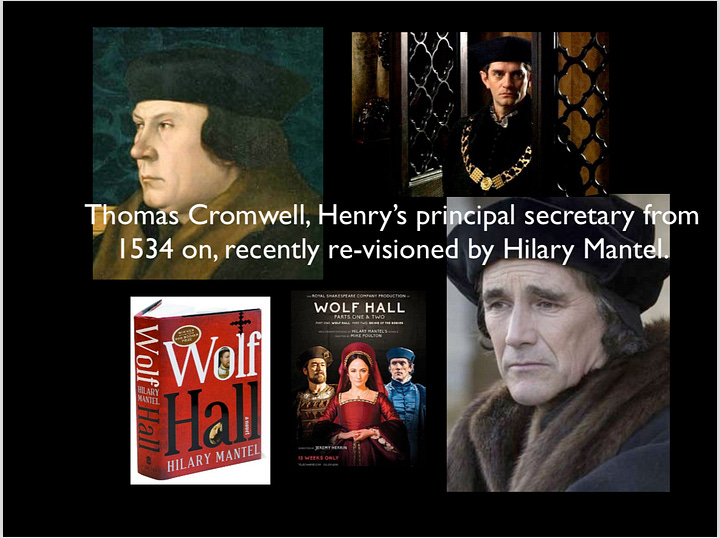

Another theory, which Alison Weir puts forward in The Six Wives of Henry VIII but revises in The Lady in the Tower, is that Henry, fed up with Anne, newly enamored of Jane, and eager “to rid himself” of his second wife but not knowing how, eagerly embraced Cromwell’s suggestion, in April, that he had information that Anne had engaged in adultery, and asked Cromwell to find evidence to support the charges.[2] But even if we accept the idea that Henry would cynically encourage a plot designed to lead to Anne’s execution, and despite his flirtation with Jane and disappointment over the latest miscarriage, Henry did not behave like someone looking to end his marriage. He knew that recognition of his supremacy was still entwined with her, and even after the miscarriage, he was still working for imperial recognition of his marriage to “his beloved wife” Anne.

With Katherine gone, it seemed a real possibility. In March, the emperor offered, in return for the legitimation of Mary, imperial support for “‘the continuance of this last matrimony or otherwise,’ as Henry wished.”[3] The deal didn’t work out, due to Henry’s refusal to acknowledge that anything about his first marriage—including Mary—was legitimate. He was utterly committed to maintaining his own absolute right to the organization of his domestic affairs, and that meant both recognition of Anne as lawful wife and Mary as bastard.

Most scholars nowadays believe, following Eric Ives, that the plot against Anne was orchestrated by Thomas Cromwell. Things had been brewing dangerously between him and Anne for some time, and by April, she probably knew that he had become friends with the Seymours and had also been sidling up to Chapuys. On April 2, Anne had dared to make public declaration of her opposition to his policies by approving of a potently coded sermon written by her almoner, John Skip, in which he (implicitly) compared Cromwell to Haman, the evil, Old Testament councilor (which would make Anne the virtuous Esther to Henry’s Xerxes.)

The specific spur for the sermon was proposed legislation to confiscate the wealth of smaller monasteries, which was awaiting Henry’s consent and against which Anne was trying to generate public sentiment. But by then, the enmity between Anne and Cromwell had become more global than one piece of legislation, and Cromwell was aware of losing favor with Henry. During a crucial meeting between the Ambassador and the King on April 18th, Henry, who had seemed to be in favor of reconciliation with Rome, now revealed his true hand, and refused any negotiation that included recognition of his first marriage and Mary’s inclusion in the line of succession. Cromwell was aghast at Henry’s stubbornness, as he had been working hard toward the rapprochement with the emperor, burned his bridges with France, and (because of his relationship with Chapuys) with Anne and her faction as well. 1

“Far from the issue of April 1536 being ‘When will Anne go and how?’” Ives writes, “Henry was exploiting his second marriage to force Europe to accept that he had been right all along.”[4] Cromwell was furious, humiliated, and fearful that he had unexpectedly found himself on the wrong side of Henry’s plans. 2 And Anne must have felt deceptively safe. On April 25, Henry wrote a letter to Richard Pate, his ambassador in Rome, and to Gardiner and Wallop, his envoys in France, referring to “the likelihood and appearance that God will send us heirs male [by] our most dear and most entirely beloved wife, the Queen.”[6]

But something had already begun to seem wrong to Anne, who sought out her chaplain, Matthew Parker on the 26th, and asked him to take care of Elizabeth, should anything happen to her. That was astute of Anne. In the days that follow, Chapuys was clearly (and gleefully) aware that plots were being hatched against Anne. He wrote to Charles that there is much covert discussion, at court, “as to whether or not the King could or could not abandon the said concubine,” and that Nicholas Carew is “daily conspiring” against Anne, “trying to convince Miss Seymour and her friends to accomplish her ruin. Indeed, only four days ago the said Carew and certain gentlemen of the King’s chamber sent word to the Princess to take courage, for very shortly her rival would be dismissed.”[7] When the bishop of London, John Stokesley, expressed skepticism, “knowing well the King’s fickleness” and fearful that should Anne be restored to favor, he would be in danger, Chapuys reassures him that the King “could certainly desert his concubine.”[8]

In fact, after the April 18th meeting, Cromwell, claiming illness, had gone underground to begin an intense “investigation” into Anne’s conduct. On April 23, he emerged, and had an audience with Henry. We have no record of what was said. But many scholars believe that the illness was a ruse, that during his retreat he carefully plotted Anne’s downfall, and that what he told the king on April 23 were the deadly rumors about Anne that eventually led to her arrest and trial. The king, however—perhaps dissembling for public consumption, or perhaps unconvinced by what Cromwell has told him—was still planning to take Anne with him to Calais on May 4th, after the May Day jousts, and was still pressing Charles to acknowledge the validity of his marriage to Anne.

Then, on April 30th, Cromwell and his colleagues laid all the charges before Henry, and court musician Mark Smeaton was arrested.

Anne had no idea that Cromwell and Henry, that day, were meeting to discuss the “evidence” that Anne had engaged in multiple adulteries and acts of treason. That evening, while Smeaton was being interrogated (and probably tortured), there was even a ball at court at which “the King treated [Anne] as normal.”[9]He may have been awaiting Smeaton’s confession, which didn’t come for 24 hours, to feel fully justified in abandoning the show of dutiful husband.

Although we don’t know for sure what message was given to Henry during the May Day tournaments, it was probably word of Smeaton’s confession, for he immediately got up and left. Anne, who had been sitting at his side, would never see him again; the very next day, as her dinner was being served to her, she was arrested and conducted to the Tower.

Anne may have unwittingly contributed to those arrests herself. “M. Kyngston,” she asked when brought to the tower, “do you know wher for I am here?” In a state of shock and disbelief, she searched her mind for the reasons for her arrest and shared her anxious musings with Kingston (who reported everything to Cromwell) and also to the ladies-in-waiting that Cromwell had chosen to spy on her.

In particular, Anne fretted about a possibly incriminating conversation she had with Norris, a long-time supporter of the Boleyns and the Groom of the Stool in the King’s Privy Council. Anne had been verbally jousting with Norris about his constant presence in her apartments, and had chided him for “looking for dead men’s shoes, for if aught should come to the King but good, you would look to have me.” This particular statement must have alarmed Norris, who replied that “if he should have any such thought, he would his head were off.”

There was good reason for his alarm: In 1534, Cromwell had engineered an extension of the legal definition of treason, which was passed by parliament, and which had made it high treason to “maliciously wish, will or desire by words or writing” bodily harm to the king. Under this new definition, Anne’s remark could be construed as referring to Norris’s desire for the King’s death. Anne apparently eventually “got it”, too, for after Norris made the comment about his head, she then told Norris that “she could undo him if she would.” What had (probably) begun as casual teasing ended with each ostentatiously declaring their horror at the thought that either entertained fantasies of Henry’s death.

But Anne worried that this wasn’t enough. Later, realizing that their remarks may have been overheard, she asked Norris to go to her almoner, John Skip, and “swear for the queen that she was a good woman.” Unfortunately, this attempt at damage control only worked to make Skip suspicious. He confided his suspicions to Sir Edward Baynton, who then went to Cromwell, who surely felt that gold from heaven had fallen into his lap. All this happened in late April. So clearly, at the point of Anne’s arrest on May 2, Norris was suspected of more than simply withholding information about her purported affair with Smeaton. However, the full details of the conversation may only have been revealed by Anne herself, in her rambling self-examination with Kingston, and this may be why Norris wasn’t arrested until May 4th.

Anne also told Kingston about how she had teased Francis Weston, then reprimanded him, for telling her that he, too, frequented her apartments out of love for her. Under other circumstances, it would undoubtedly been regarded as innocent, courtly banter. But…what was considered “courtly” and what was suspected to be something more had changed since Anne had learned the rules, and Cromwell was able to take advantage of the different climate with regard to heterosexual behavior.

The times, to anachronistically poach from Bob Dylan, were a ‘changing. Yes, Anne had failed to produce a son for Henry VIII, and yes, Thomas Cromwell had his own reasons to plot against her. Yes, she had many enemies at court, and yes, there was Jane Seymour waiting in the wings, with the promise of greater obedience than feisty Anne and fresher eggs for the incubation of a royal heir. None of these factors, however, could have sent Anne to the scaffold had the charges of adultery and treason seemed utterly preposterous to the Tudor jury, for the Tudors were great believers in “the law,” and it was important to Henry that the “appearance of justice,” at the very least, seem to have been done. What helped make that travesty possible, I believe, was a cultural change in the interpretation of courtly banter, which Anne engaged in—innocently but as it turned out, fatally.

Anne was trained in traditions of courtly love within which flirtatiousness, far from being suspect, was a requirement of the court lady. But it must never go too far; the trick was to just go to the edge and then back off (without, of course, hurting the gentleman’s feelings). Purity was required, but provocative banter was not just accepted, it was expected. Especially in the French court, where Anne had spent much of her young adulthood, a relaxed atmosphere was the norm in conversations between men and women. But as the Middle Ages segued into the Renaissance and then into the Reformation, people may have become disposed to believe things, based on the exchanges with the men Anne was charged with, that would have been dismissed as ridiculous forty years earlier.

Even in Henry’s courtship of her, Anne got caught in the net of changing romantic conventions. Henry had been raised on tales of King Arthur’s round table, virtuous knights, maidens in distress and chivalrous deeds. Nobility, generosity, mercy, justice, and the power of true love were the stuff of his boyish fantasies. However, by 1526, when Henry began to pursue Anne, Arthurian chivalry, a deeply spiritualized ideal, was well on its way to being transformed into the political “art” of courtly behavior, aimed at creating the right impression, even if deceptive, to achieve ones ends. In his letters to Anne, Henry gives her the impression that she is his Guinevere, and he her loyal servant: “I beseech you,” “if it pleases you,” “begging you,” “fear of wearying you,” “your loyal servant”, “to serve you only.” Etc. etc. Deeply felt emotion, or a pleasurable fiction, designed to woo and win?

Henry was in love, yes. But he was never the helpless swain that he makes himself out to be in his letters. And although he believed in Arthurian honor, which served and protected women as one of its highest goals, he could never have done what Arthur (in the legend) had done: stand nobly and patiently by while his best knight and his wife engaged in a long affair.

In the legend, Guinevere is condemned to death twice for treason (the second time for adultery with Lancelot) and both times is saved from the stake by Lancelot—with King Arthur’s blessings. Arthur had, in fact, suspected the queen’s infidelity for years, but because of his love for her and for Lancelot, had kept his suspicions a secret. When Modred and Aggravane, plotting their own coup d’etat, told the King about it, he had no choice but to condemn his queen, while privately hoping she would be rescued. It was a romantic fantasy—but one which Henry and Anne had grown up with, and which no doubt shaped their ideas about love. Henry had himself been an adroit and seductively tender courtier, who had pledged himself Anne’s “servant” and swore his constancy. The pledges may (or may not) have been made manipulatively, but his infatuation was real and the gestures were convincing.

Until very near the end, Anne had hopes Henry would spare her. Henry had in fact honored her like Guinevere for six years, and if things went according to the old courtly script, she had every reason to believe Henry would spare her, as Arthur did with Guinevere. But Henry lived in a time when kingly authority—not “knighthood”—was in flower. So while Guinevere, who actually had a sexual relation with another man, was saved by Arthur, Anne Boleyn—guilty of nothing more than a bit of courtly banter—was sent to the scaffold, and Henry never looked back.

Stay tuned for my next excerpt—on the famous tower scene from “Anne of the Thousand Days,” with an exclusive interview with Genevieve Bujold.

Interested in my book? For reviews, interviews, articles, photo gallery, articles, an audio excerpt and to order, see my website:

********************

1] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: December 1533, 16-25,” Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 4 Part 2: 1531-1533, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=87796&strquery=”soenchanted and bewitched him”

[2] (Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII 1991, 309)

[3] (Ives 2005, 312)

[4] (Ibid., 315)

[5] James Gairdner (editor), “Henry VIII: April 1536, 21-25,” Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 10: January-June 1536, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=75427&strquery=”kiss or speak”

[6] Weir, Lady in the Tower, p. 95.

[7] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: May 1536, 1-15,” Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 2: 1536-1538, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=87960&strquery=”couldnot abandon the said concubine”

[8] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: May 1536, 1-15,” Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 2: 1536-1538, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=87960&strquery=”deserthis concubine”

[9] (Weir, The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn 2010, 123)

Earlier in the day, it had seemed that some kind of warning between Chapuys and Anne was being orchestrated. Chapuys had been invited to visit Anne and kiss her hand—which he declined to do—then, was obliged to bow to her when she was thrust in his path during church services. Later, at dinner, Anne loudly made remarks critical of France, which were carried back to Chapuys. But when after dinner, Henry took Chapuys to a window enclosure in his own room for a private discussion, he made it clear that he wouldn’t give.

In a letter to Charles, Chapuys wrote about the April 18 meeting, and what he wrote suggests that what was already on high heat between Cromwell and Anne was about to boil over. Chapuys reports that one reason why he would not “kiss or speak to the Concubine” and “refused to visit her until I had spoken to the King,” was because he had been told by Cromwell that the “she devil” (Chapuys’ appellation, not Cromwell’s) “was not in favor with the King” and that “I should do well to wait till I had spoken to the King.”[5]

Excellent Ms. Bordo. I checked your home page. Get your book front and center! Someone told me a book should be a "two click buy" and I liked that

Excited to read your book! Thank you for the excerpt.