I’ve been writing about cultural imagery, eating disorders, our cultural horror of fat, the global spread of eating problems, and the meaning of the thin body for over thirty years. My first piece on eating disorders was published in 1985; it was among the very first discussions to go beyond medical explanations to consider the role of images, gender roles, and consumer culture, and was following by many articles and three books on the body in historical and contemporary context.

Most of that writing was not overtly personal. Meaning: I didn’t talk much about myself. I was trained as a philosopher to leave personal experience out of my work. Of course, that’s impossible; it’s either there explicitly or covertly—and eventually (after I’d proved I was “a philosopher”) I began to write very differently. But that happened after I’d published my best-known work on fat, thin, and the female body. Looking through those books and articles, I am amazed both at how “in the closet” I was—yet there on every page.

Here are some pages where I opened that door.

Walt Disney Made Me Diet (From TV, 2021)

Until my younger sister was born, I was the baby of our family. Then, when I was four, she was brought into the house and I began to eat. First, I’m told (it may be a family myth), it was her toe, which they say I tried to bite off the first night she came home. Then it was chunks of white bread, gauged from the middle of the loaf, compressed into chewy lumps and dunked in mustard. I had to do my binging when no one was home, though, as my father himself in those days was fat and I became his shame-surrogate — not only for over-eating but for failure to “stick to” anything: diets, learning to swim, finishing school assignments. “You’re just like your Aunt Etta,” he’d say scornfully, disgust twisting his mouth; she was even fatter than he was and branded as the “lazy one” among his siblings.

I got fatter and fatter, and more and more afraid and ashamed of my body. I couldn’t climb the ropes or jump over the horse in gym class, and the gym teacher shook his head scornfully and occasionally called me names. I dreaded going to school and each morning, pretending sickness, I would hold the thermometer near the radiator. Once I went too far and it burst, causing shape-shifting droplets of mercury to spray all over the linoleum floor. They were fascinating to look at as they scurried this way and that, but I’d heard mercury was poisonous, so I had to call my mother in. She let me stay home anyway; suffering from depression herself, she couldn’t deal with my sobbing when forced to go to school.

When my half-brother got married, they took me to Lane Bryant to get a dress. It was a hideous thing, with an enormous floral bloom right in the middle of my chest, I suppose to distract from the body that wore it. Although I was approaching adolescence, they made me march in the “children’s parade”; I was easily the biggest marcher, my head down and cheeks burning, and when the wedding photos were shown around, I begged my parents to throw away the ones in which I appeared. Of course, they didn’t — but when I finally got my own hands on copies, I cut myself out of all of them.

The Mickey Mouse Club, which premiered in 1955 when I was probably at the nadir of self-shame, found an especially ripe target in me. Does “target” seem excessively conspiratorial? The fact is that Walt very consciously set out to exploit the potential of baby boomers as consumers, as did all the kids’ shows. They had a powerful sales tool: “Most of the children’s-show hosts were hucksters in the guise of father figures. There was the friendly hunter (Buffalo Bill) or a friendly museum watchman (Captain Kangaroo) That combination of warmth and authority . . . was a powerhouse sales tool. If Dad says Wonder Bread is good for you, then it must be true.”

From the beginning, The Mickey Mouse Club was a bonanza for merchandisers. The show featured more ads than any other at the time—twenty-two per episode. And Disney was (and “Disney, Inc.” still is) a master at commodifying entertainment, from Davy Crockett hats and Spin and Marty books to tie-ins with Mattel toys. In 1955, when Club premiered, Mattel had annual sales of four million dollars. That Christmas, it began to advertise on Mickey Mouse Club; within a few years sales topped thirty-five million.

Shown from left: Jimmie Dodd, Annette Funicello, Tommy Cole, Doreen Tracey. Walt Disney Pictures/ABC/Photofest

A huge source of revenue came from the promotion of mini-stars whose every fashion choice and hobby, featured on the pages of teen magazines, afforded opportunities to sell, sell, sell. At the beginning of each show, the chosen ones proudly introduced themselves: “Annette!” “Darlene!” “Cubby!” “Bobby!” Mouseketeer hats? If you were born in the years between 1946 and 1952 it’s highly likely you had one. But the most enviable Mouseketeer for me—Annette Funicello—didn’t just have a hat with ears and a cute little plaid pleated skirt. She also had breasts—at first modest, but growing more prominent with every season, eliciting both adolescent lust and snickers from the boys and teaching girls, as Susan Douglas remarks, that whether desired or demeaned, they were defined by their bodies..

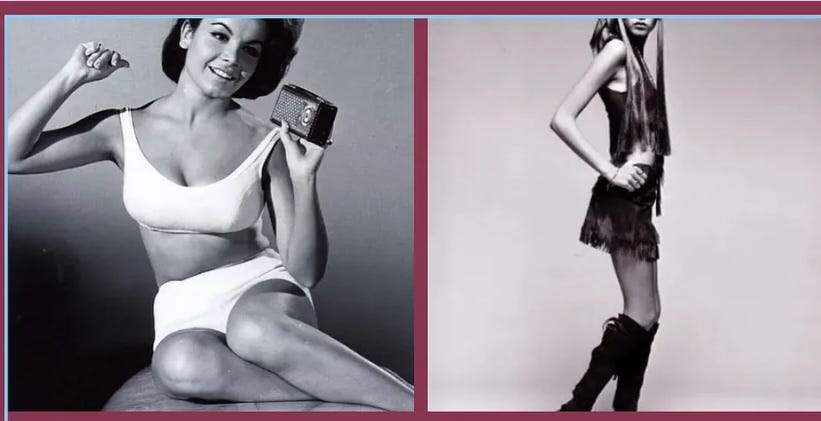

Fashion has always been a harsh dictator. But in previous twentieth-century periods, the dissemination of images was limited to high fashion magazines or, for those who couldn’t afford Chanel, sketches in Sears Roebuck catalogues. The post-war period changed all that. There was a new consumer—eventually to be called baby boomers, first generation to constitute a distinctive “youth market”—and there were new media (teenage-geared movies, magazines, television shows) to pump up our desire, our desperation to look like the teen celebrities (and a little later on, the models) that seemed so perfect to us. Photo spreads designed specifically for teens now began to dictate our fantasies and expectations more than books. Goodbye Jo March, hello Gidget.

The most desirable teenage body in the early Sixties, when a return to domesticity was still winning out over the cool, androgynous look emerging from Carnaby Street, was a version of the hourglass. Annette had a tiny waist and perky breasts, as did Sandra Dee, as did Connie Stevens and teenage Elizabeth Taylor; it was a feature that was accentuated by the belted shirtwaist[A6] dresses favored in those days. I had the potential but was about twenty pounds overweight by the standards of those times, so the summer before high school I began the endless cycle of dieting—losing weight—gaining weight—dieting—gaining weight—that had been a constant in my life. After a summer of cottage cheese and hamburger patties without the bun, I started high school on the hottest day of the year in a tightly belted form-fitting burnt-sienna-colored wool dress that I had chosen for the reveal and wasn’t going to give up no matter how scratchy it felt.

For a while, I looked “right.” Unfortunately for me, by the time I was a junior in high school, being small breasted and long limbed was in style. While I could approximate the curvy idea of the Fifties through diet and the right kind of bra, my 5-foot 2-inch, big-booty body—shaped by centuries of Eastern European genes—made it impossible for me to look anything like a Twiggy, or even a Peggy Lipton of The Mod Squad. To add insult to injury, my bust—the one feature of my body that had satisfied the “mammary madness” of the 1950s—was now not just out of fashion, but an embarrassing signifier of an out-of-date ideal of femininity. The hourglass figure had been valued as the symbolic embodiment of a domestic (male-sexualized, reproductive) destiny. The flat-chested, lanky look, in contrast, made you a cool girl who had the sexual ease and the social freedom that I craved. As for my big booty, I was too old to personally benefit, but not too old to appreciate it when hip-hop took its revenge.

.

Since then, there have been long periods — until menopause — in which I was relatively slender, and I never again let myself approach a weight which would allow me to be classified, as I had been in childhood, as fat. Men found me attractive, and — as for many women with body-shame — their sexual attention became a drug. It offered proof that fat little Susie Klein was no longer in the room, and dulled the fact that no matter how slim I was, I still hated my thick calves and ankles. When a lover held my legs up and kissed them all the way from chunky foot to hefty thighs, gratitude flooded me and I felt reborn.

Once you have been fat, however, the shame never really leaves you. When after menopause I began to slowly gain 10–20–30–40–50–60 lbs., it became a horror, once again, to look full-body in the mirror. The disgust that I felt as a child was back with me again, only this time accompanied by the uncanny body-changes that aging brings. Seeing an overweight body was familiar. This 77-year-old body is a stranger. I’d always had a defined waist; now it’s virtually gone. My skin was smooth; now it’s crinkly. My boobs were full and shapely, but never huge; now I wear a bigger size bra than I’d ever imagined. At 77, too, getting my weight down has become a necessity for the control of blood pressure and avoidance of diabetes.

Health concerns, yes. But little Susie Klein, who cut herself out of pictures, is still there as I step on the scale.

Never Just Pictures ( From Twilight Zones: The Hidden Life of Cultural Images from Plato to O.J., 1997)

Why are cultural images so powerful?

For one thing, they are never “just pictures,” as the fashion magazines continually maintain (disingenuously) in their own defense. They speak to young people not just about how to be beautiful but also about how to become what the dominant culture admires, values, rewards. They tell them how to be cool, “get it together,” overcome their shame….

To girls who have been abused the abolition of “loose” flesh, through diet or exercise, may speak of transcendence or armoring of a too vulnerable female body. For racial and ethnic groups whose morphology—large buttocks, “big” legs--have been marked as foreign, earthy, and primitive, mainstream images may cast the lure of assimilation and acceptance. Often the fear of being "too fat” will have a strong sexual association. One woman writes:

"Being fat meant that I had uncontrollable desires, that I was voracious. It was a clear danger sign to men: stay away, this woman will eat you up.... Appetite equals sexual appetite; having a sundae is letting go. Eating that cake and ice cream meant I wasn't getting sex, and look how much sex I must need if I had to eat so much to compensate. Since I couldn't control myself around food I wouldn't be able to control myself around men; since no food ever satisfied me, no man ever would. "

While looking through old diaries of mine, I came across an entry that revived disturbing memories for me. It was written during a time when I had been ill and depressed and had consequently lost a great deal of weight. I was thin to the point that I no longer felt I looked very good, and I was withdrawn and anxious most of the time. I wrote:

I've suddenly realized that deep inside me, I am convinced that men will find me more attractive in my diminished state. X's cousin this past week-end mentioned how good I looked, and I felt that he found me attractive. Here's how I was: skinny, no makeup, hair lank and dirty. I remember when I was so depressed that other time, got down to 114 pounds, and could barely do anything;Y wanted to have sex with me all the time.... Here is the way I used to be: robust and Jewish, brainy, forceful, demanding, conscious, conscious, conscious. Now I am so much less, both physically and in terms of assertiveness ... and I'm aware of how drawn men are to me.

Reading this entry was chilling. I had forgotten about those moments when I suddenly realized that some man was attracted to me because I was "less." Remembering those moments, I was reminded of a truth that is hard to face, about the personal price women may pay for increased presence and power in the world, and the personal rewards they receive for holding back, keeping themselves small and tentative.

Anxieties about women as "too much" are also layered with racial and other associations that, contrary to the old clinical cliches, set up black, Jewish, lesbian, and other women who are specially marked in this way for particular shame…We may grow up sharply aware of representing for the dominant WASP culture a certain disgusting excess-of body, fervor, intensity-which needs to be restrained, trained, and, in a word, made more "white." A quote from poet and theorist Adrienne Rich speaks to the bodily dimension of "assimilation":

"Change your name, your accent, your nose; straighten or dye your hair; stay in the closet; pretend the Pilgrims were your fathers; become baptized as a Christian; wear dangerously high heels, and starve yourself to look young, thin, and feminine; don't gesture with your hands.... To assimilate means to give up not only your history but your body, to try to adopt an alien appearance because your own is not good enough, to fear naming yourself lest name be twisted into label."

I include myself here, as a Jewish woman whose body is unlike any of the cultural ideals that have ruled in my lifetime and who has felt my physical "difference" painfully. I have been especially ashamed of the lower half of my body, of my thick peasant legs and calves (for that is indeed how I represented them to myself) and large behind, so different from the aristocratic WASP norm. Because I've somehow felt marked as Jewish by my lower body, I was at first surprised to find that some of my African-American female students felt marked as Black by the same part of their bodies. I remember one student in particular who wrote often in her journal of her "disgusting big black butt." For both of us our shame over our large behinds was associated with feelings not of being too fat but of being "too much," of overflowing with some kind of gross body principle. The distribution of weight in our bodies made us low, closer to earth; this baseness was akin to sexual excess (while at the same time not being sexy at all) and decidedly not feminine.

We didn't pull these associations out of thin air. Racist tracts continually describe Africans and Jews as dirty, animal-like, smelly, and sexually "different" from the white norm. Our body parts have been caricatured and exaggerated in racist cartoons and "scientific" demonstrations of our difference. Much has been made of the (larger or smaller) size of penises, the "odd" morphology of vaginas. In the early nineteenth century Europeans brought a woman from Africa-Saartje Baartman, who came to be known as "The Hottentot Venus"-to display at sideshows and exhibitions as an example of the greater "voluptuousness" and "lascivity" of Africans. Baartman was exhibited as a sexual monstrosity, her prominent parts an indication of the more instinctual, "animal" nature of the black woman's sexuality.

When the female "Other" is not being depicted as a sexually voracious primitive, she is represented as fat, asexual, unfeminine, and unnaturally dominant over her family and mate-for example, the Jewish Mother or Mammy. The associations are loaded even more when sexuality enters in. As one woman notes, "As a Fat Jewish Lesbian out in the world I fulfill the stereotype of the loud pushy Jewish mother just by being who I am (even without children)!" The same woman remarks that the culture of the nineties has "brought a new level of fat hatred within many lesbian communities ... [an] overwhelming plethora of personal ads which desire someone fit, slim, attractive, passable, not dykey, athletic, etc."

That "not dykey" and "slim" are bedfellows here is not surprising. An older generation of lesbians who dressed in overalls and let their hips spread in defiance of norms of femininity may be as much an embarrassment to stylish young lesbian as the traditional Jewish mother is to her more assimilated daughters….

How the Body Speaks. (2020, From a discarded prologue for a book on the body that I never wrote)

The body doesn’t let us forget what academics call “materiality”

Judy Collins was on my IPad; I was in that kind of mood. My little Havanese, finding no available lap or shoulder, was lying on my hands; his body was like a muff, warm and soft, and occasionally I rested my forehead against it. I was feeling sorry for myself. My back had been aching for a few weeks when one day the pain shot fiercely from a spot just under my waist, down my left leg, and into my foot. After advil and ice, the sharp pain had gone away, leaving a trail of tingling and numbness down my leg and foot, and when I stood up, my left leg had altered it’s previously compatible relationship with the left. “Shit,” I thought, imagining stair lifts and motoring through the supermarket, “I’m really an old person now.”

The chiropractor diagnosed several not-very-unusual problems for a person of 74, prescribed regular sessions, massage, and at-home stretches several times a day.

So—the downward dog. It apparently shifts some nasty gunk oozing from between compressed discs back where it belongs (“Think of the jelly in a jelly donut being squeezed out,” the sciatica guru on the internet had said. It was all a mystery to me, but it did feel good.)

“Alexa, play ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ and others like it.”

I’m sure Judy, dreaming with her love before the winter fire, and my dog, who adored and wanted to merge with every part of my body, had something to do with it. But my hips and bottom, made unyielding by years of sitting and writing, allowing my brain to take control, sent a stream of emotion upward, away from my numb legs toward my heart, which—amazingly—was not yet in lockdown. My elbows were on the mat, my back arched, butt high and reaching out, not to obey the instruction booklet (“exercises for back, sciatica, ec.”) but for the pure joy of it—and then suddenly I was weeping, as a secret history stored in that part of my body came unpacked.

We’d been together only a short while, and were obsessed with each other. My body yearned for his so badly that even when we weren’t together, I’d feel him physically. Sometimes at night, half-asleep, his naked chest would be against mine, and I was shocked to realize that he wasn’t actually there. It wasn’t a dream, I’m sure of that, but some kind of psychic/body conjuring I can’t explain. I can’t explain, either, how it was that during one ecstatic coming-together on my bathroom floor, my legs wrapped around this man who loved them, thick ankles and all, I knew—absolutely, definitively knew—the moment I got pregnant. A soundless “ping.” My doctor scoffed—“You can’t feel the sperm penetrating the egg”—but he was wrong, totally wrong.

A bit later after my Judy Collins moment, my back resting against a huge blue ice pack, I thought about all that my body knew, all the times it had said to me: “See, you can’t ignore me, control me, or escape me. I’ll catch up with you, for better or worse.” It was for better the night at Arthur Murray’s when I discovered that my big-bottomed, big-legged pear of a body could do Cuban motion as if born to it (where did that come from, in this shame-ridden Jewish girl?), while the slender reeds across the room struggled. For better, too—and as authoritative, in their own way as my pregnancy “ping”--were the labor pains I felt when the birth mother of my daughter-to-be, across town, was experiencing the real thing---at the exact same time.

The body also speaks metaphorically:

Years earlier, having tried to get pregnant without success, my ears got blocked, and it developed—as has happened several times in my life, though taking root in different parts of my body—into a somatic phobia so preoccupying that it necessitated taking a leave from teaching. I experienced my ears as filled with tunnel-like tubes travelling from outer to inner and back out again. And yet it came with a jolt when, explaining the sensation to my therapist, I referred to the malfunctioning working of my inner ear as fallopian tubes.

All of this, on the face of it, seems merely autobiographical. But only on its face. In fact, my body—all of our bodies—contain knowledge that although intimate and shaped by the particulars of each individual life operates, like all languages, within a larger lexicon of meanings, meanings that themselves branch out in myriad directions.

A “Jewish” body performing “Cuban motion” is not just about Susan Bordo discovering an ability she didn’t know that she had. It’s about the sexual organization of the body, biologically as well as historically, it’s about ethnic shame over body parts (not exclusive to Susan Bordo, certainly), and it’s about, as well, the unexpected forms of human connections that our racially divided culture doesn’t allow for.

I have a butt like a Black girl, and in many ways that have nothing to do with skin color, I don’t think of myself as “white.” But while In theory, we recognize that “white” is a historically shifting designation of political and social power and privilege—not a biological category—if I dared speak (on MSNBC, say) of my identifications with Black women, I’d be harshly scolded for not recognizing the privilege my skin color confers. I’d have to qualify and explain (“Of course, I’m not saying that a policeman wouldn’t treat me differently than a person with brown or black skin,” “Of course, I’m not saying that I know what it feels like to be a Black woman,” etc. etc,) I’d have to backtrack and pander, and we’d never get to explore the complexities of race together, or the possibilities for a deeper coalition than putting a “Black Lives Matter” sign in my window, and being a good—but silent—“ally.”

Poet Carolyn Williams , in the middle of heated controversies about the taking down of Southern monuments glorifying the Confederacy, published a piece called “You want a Confederate Monument? My body is a Confederate Monument.” It begins: “I have rape-colored skin. My light-brown-blackness is a living testament to the rules, the practices, the cause of the Old South. If there are those who want to remember the legacy of the Confederacy, if they want monuments, well then, my body is a monument. My skin is a monument.”(Williams, 2020) There couldn’t be a more perfect example of displacing the “objectivity” of the conventional color-palate with complexion as “written” by history—in this case, a history that is both racist and patriarchal.

Williams’ essay is powerful, and gifted readers with the jolt of what in the old days of feminism we called the “click” of recognition that the “personal is the political”--possibly the most famous slogan produced by what has been called (sometimes derisively, sometimes nostalgically, but rarely with the intellectual credit that is it’s due) the “second wave” of feminism. In those days, it referred to the “aha!” insight that encouraged women to understand their individual wounds, angers, desires, and difficulties in relationships , jobs, and school as far from unique, but systemic to the situation of being a woman in a patriarchal, sexist culture.

Your boyfriend refuses to do the dishes? Click! Such chores are an arena for “the politics of housework.” You can’t reach orgasm except through masturbation? Click!! Your privates are a colonized territory, and patriarchy has deemed penetration of the vagina the only “real” sex, the clitoris just an immature little vestige of pre-grownup femininity. You are ashamed to talk about the date who raped you (after all, you were drinking, and wearing a mini-skirt)? Click! We live in a “rape culture” in which boys are taught sex is owed them and girls learn they themselves are responsible for the sexual violence done to them. Your shoulder is on the verge of dislocation from waving to answer questions in class, as the professor’s eyes glaze over you until he lights on the half-raised arm of a boy? Click? Welcome to Sexism 101. So you get a little more pushy, and then they call you a bitch, a ball-buster, a bull-dyke. Click, click, click, click!

A lot of great feminist writing emerged from that insight, writing that firmly kept in mind the “is” yoking the individual to the systemic. And much of it was about the body—not as the dictator of biological reality but—as Carolyn Williams described it in her powerful essay--as a storehouse of historical, political and cultural meaning. Germaine Greer wrote a whole book unpacking those meanings through a tour of female body-parts. But that kind of nuanced exploration isn’t the stuff of rallies, and in 2021, it’s largely been left to memoir and sharing among close friends (or with therapists,) as “political action” turns to the generalizing language of marches and manifestoes.

Sadly (from my point of view), feminist “personal politics” has become almost entirely ideological, even about those experiences that are intensely intimate and individualized. As a result, complexity, ambiguity, context, and the “intersectionality” that we tout in theory rarely operates “in action.”

The actualities of who has power over whom are often much more complicated than the formulas allow for. When I was a 26-year-old sessional lecturer I had an affair with an 18-year-old student, and briefly referred to it on Facebook, where I was pelted with sanctimony and horror. “What kind of a feminist are you????” “I’m blocking you right now.” “You’re disgusting!” “How could you? I would have expected so much better from Susan Bordo” The fact is—and I will write more about this in the book—that 18-year-old held plenty of power in the relationship; more than I did, actually. But to understand that, you have to understand “power” not as something one either possesses (or doesn’t) but is distributed socially along a variety of axes, not just “boss/employee,” “teacher/student” or “male/female.” Power is….well….intersectional.

It’s impactful to see & read these three pieces together. Thank you for sharing them.

I have been inside of many different bodies through the years, and just when I felt able to organize all the cumulative weight of so many stored “bodies,” pain & disease showed up to teach me that all the many versions of me still add up to just one: The one I’m trying to hold onto for longer and with less pain.

Wow, so much to unravel. Many memories resurfaced when reading this piece. Memories that I'm not trying to suppress but that take a long time to work through. Your truth speaks to every woman.