Is “The Other Boleyn Girl” Based on Fact?

We’ve had a lot of fanciful versions of Anne Boleyn lately, but Philippa Gregory’s, although perhaps the most fictional of all, is still believed by many to be based on fact. Spoiler: It’s not.

Note: This is a highly condensed excerpt from my 2013 book The Creation of Anne Boleyn, which discusses historical, fictional, stage and film versions of the life and death of Anne Boleyn. Since it was published—and especially during the past several years—new versions of Anne have popped up that I will discuss in later posts. I start with this excerpt because I was surprised to see that the issue about The Other Boleyn Girl’s accuracy, which I had thought to be settled by now, is apparently still a live question, e.g. this piece, published today: “Is The Other Boleyn Girl Based on a True Story? “]

In 2002, Robin Maxwell, who had written a highly-praised novel about Anne, The Secret Diary of Anne Boleyn, was given a new manuscript to read. Arcade editor Trish Todd wanted to know, would Robin give it a blurb?

The manuscript took Maxwell by surprise. Most novels about Anne that were written in the 1980’s and 90’s had been quite sympathetic toward her. Maxwell’s own book (1997)is constructed around the delightful fiction that daughter Elizabeth discovers Anne’s diary and learns how much her mother loved her and how “cruel and outrageously unjust” her father had been; the knowledge redeems Anne in her daughter’s eyes and sets Elizabeth up for a lifetime of caution about giving the men in her life too much power. In Jean Plaidy’s beautifully wrought The Lady in the Tower (1986), we find Anne imprisoned, thinking back on her life, wondering “how I had come to pass from such adulation to bitter rejection in three short years”; her reflections are those of a mature, regretful, clear-sighted woman, capable of recognizing her own faults, but very much aware of how her own mis-steps had been cruelly exploited by others. This new book, however, seemed to Maxwell to be a modernized recreation of the old Catholic view of Anne as a scheming viper.

“I was appalled,” Robin recalled in a phone interview with me. “It was a great read, a page turner. But she had taken every rumor, every nasty thing that anyone had ever said about Anne Boleyn and turned it into the truth in her book. You can argue that she had every right because she’s a historical fiction author, but I refused the blurb on principle because of its vicious, unsupportable view of Anne.”

The book was Philippa Gregory’s The Other Boleyn Girl. In it, the character of Anne is indeed more selfish, spiteful, and vindictive than she had appeared in any previous novel, a nasty, screechy shrew who poaches Henry from her generous, tenderhearted (and very blonde) sister Mary and proceeds to tyrannize her (and everyone around her), barking out orders, plotting deaths, appropriating her sister’s child, and—when she miscarries her final pregnancy with Henry—coercing her brother George to have sex with her. Neither “Sleeping Beauty” nor “Cinderella” strike a more clean-cut division between the good and the wicked woman, with Anne playing the role of the wicked witch and Mary the long-suffering, virtuous heroine. As in any other fairy tale, however, the good are ultimately rewarded and the evil are punished. Anne, having gone to “the gates of hell” with her brother in order to get pregnant, miscarries a deformed child (an idea that Gregory picked up from Retha Warnicke’s 1989 biography), is accused of witchcraft, and goes to the scaffold (in far less dignified fashion than history records) while Mary, with Elizabeth in her arms, retires to a bucolic life with husband and children.

Gregory describes herself as a “feminist, radical historian” and Mary Boleyn as a feminist heroine—apparently because she has sex and yet isn’t portrayed as “bad.” (I thought we went past that—and then some–with Bridget Jone’s Diary, “Ally McBeal” and “Sex and the City”.) Her novel allows Mary to be both sexual and saint-like, and despite having been “used” sexually by Henry, she is rewarded with the best ending of anyone in the book (which just happens to be a life of domestic happiness). “Mary’s story is one of absolute independence and victory,” Gregory says, and a “triumph of common sense over the ambition of her sister Anne.” Huh? Sex is allowed, but ambition isn’t? What kind of feminism is this?

There’s no doubt that Gregory plays fast and loose with history in The Other Boleyn Girl.

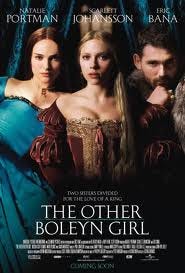

And it got far worse when the book was made into a movie. The screenplay, written by Gregory and Peter Morgan (The Queen, The Last King of Scotland, Frost/Nixon), contributed fresh inventions to the story. Michael Grandage, who directed the HBO drama Frost/Nixon, credits Morgan with the ability to weave a fictional storyline “so deeply” into a factual situation “that audiences don’t know where the boundaries of truth lie.” In the case of The Other Boleyn Girl, the “interwoven” fantasies/fictions included a gratuitous (and utterly out-of-character) rape of Anne by Henry, Mary begging Henry for a last-minute pardon for Anne, and a heroic capture of Elizabeth by Mary, who strides into court after Anne’s execution, grabs her niece, and—with the whole court watching and not lifting a finger—leaves the palace with the future queen in her arms. Oh, and another trifle—“The movies manages to virtually edit out a rather large historical fact: the Reformation”[1] As Gina Carbone puts it in her review, “Let’s just say you shouldn’t watch this and base any Jeopardy answers on it.”

The actors, apparently, did little research beyond reading the novel (Gregory commends Scarlett Johnson, who played Mary Boleyn, for having “her copy of my book in her hand practically all the time we were on set”), learning how deeply to curtsy from an etiquette coach (“It was those kinds of things’”says Johannson, “that added to the freshness and authenticity of the period”), and mastering the English accent. Natalie Portman, who played Anne, admits to not “relating” to her character, but appears to be so postmodern in her approach to history (perhaps due to her Harvard degree) that it didn’t matter much: “You have to accept that all history is fiction. All you get from history is competing views.” Eric Bana didn’t even bother with checking out the history books. “Look,” he told the director Justin Chadwick when offered the part, “I’m not someone who ever envisaged myself playing a king, or anything like that. But Henry, the guy, I think I can get to the core of him and I want to play him just as a man, that’s all I know. So I just used that. I didn’t get too bogged down in history, because I felt like at the core of it, it was kind of irrelevant.”

Not getting “bogged down” in history mattered to some, and not to others. “No matter what criticisms The Tudors may have received for its inaccuracies,” one reviewer wrote, “the Showtime series seems like a History Channel documentary compared to this movie.” But others didn’t care whether or not, for example, Anne actually propositioned her brother. “It makes for a juicy and shocking footnote,” shrugged Rex Reed, tellingly conflating the apparatus of scholarship with an “event” that has been pretty thoroughly shown by scholars to be Cromwell’s invention. And now that it has become culturally referenced by the film, a whole new generation, with little background in history but an extensive media education, has become vulnerable, once again, to the argument. “Well done and beautifully produced,” proclaims the headline of one review, “Satisfactorily explains the incest charge against Anne Boleyn.” This is what Mark Lawson has called the “Oliver Stone phenomenon’, referring to the sizeable number of Americans who believe Oliver Stone’s film “JFK” to be an accurate portrayal of an actual conspiracy to kill Kennedy.

Of course, if my book has demonstrated anything at all, it’s that neither The Tudors nor The Other Boleyn Girl has a monopoly on the creative uses of a history that, after all, has some very large holes in the record. Nell Gavin, whose ingenious and moving Threads follows Anne through several reincarnations, is based on a metaphysical premise that many readers find dubious, Anne of the Thousand Days cooks up a fictional exhange between Henry and Anne that not only did not happen but is almost unimaginable, Norah Lofts’ The Concubine has Anne engaging not just in one but multiple, anonymous acts of adultery, Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons conveniently omits Thomas More’s heretic-burnings from among his other hobbies, and Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall has Cromwell suspicious of Anne from the very beginning of their relationship, whereas in fact they were allies for much of her reign. These depictions are not just accepted without protest, but prize-winning, beloved, admired. So why should we expect different from Gregory?

What’s most disturbing are not Gregory’s distortions of fact, but her self-deceptive and self-promoting chutzpah. “Because I am a trained historian,” she wrote in 2008 (in fact, her degree is in 18th century literature), “I described the story of the Boleyn girls in the full context of the dramatic political, religious and social changes of the time. Without realizing it, in so doing I invented a new way of writing the historical novel in which the ‘history’ part of the equation is just as important as the ‘novel’ part. The fact plays as great a part in the story as the fiction, and when there is a choice of fact or fiction, I always choose the factual version. The only time that I create events for my real-life characters is to join up one factual event and another, to fill in the gaps of their story.” She describes herself as a scrupulous researcher who “applies very strict rules of accuracy” to her novels: “I read tons of primary and secondary material on a subject,” she said in a 2010 interview, “and then, using the absolute facts of a life as the bones of a story, that’s what I write.” What does she supply as a novelist? Only “the bits that we don’t know” and “feelings, because we don’t know how people felt.”

In the case of Anne Boleyn, “the bits that we don’t know” are far more plentiful than the bits that we do know, so Gregory has given herself plenty of room to maneuver—as a novelist. But Gregory wants to defend her narrative choices as history, too, although waveringly. In one interview, Gregory described the “made up bits” as speculation about what was “fairly likely.” In a Q and A appendix to The Other Boleyn Girl, however, she went further, claiming that all her choices “can be defended as historical probability” and then still further, with bold statements such as “Anne Boleyn was clearly guilty of one murder” (and probably another, she implies) and—in another interview—“Anne’s incest is powerfully suggested by the historical record” (“the historical record” here seems to be the fact that she was found guilty.)

It’s Gregory’s insistence on her meticulous adherence to history that most aggravates the scholars. David Loades: “What is important is that the author should be honest, and not claim an historical basis which does not in fact exist. It would have been safer if Philippa Gregory had claimed to be writing fiction, because that is what she was doing.” Instead, Gregory’s website repetitively intones the mantra that her work is “absolutely rooted in the historical record.” “I’m passionate about getting things right,” she says in a 2008 interview. (The example she gives: a “long investigation,” for the movie, “of precisely when riding sidesaddle first being known in England.”)

I wouldn’t be hammering away at Gregory if it were only her arrogance at issue. But the fact is that many of her readers take her at her word, and consider The Other Boleyn Girl to be a historically accurate recreation of events that actually happened. I’ve gotten plenty of direct evidence of this from audiences at my talks when I ask the opening question: “What do you know about Anne Boleyn?” “Six fingers” comes first (one myth Gregory isn’t responsible for.) Then: “She slept with her brother.” “She gave birth to a deformed child.” Sometimes, people will argue with me over the “facts” that they’ve learned from the book. Others have had the same experience:

“I think people assumed Gregory’s portrayal of the main characters had to be, in essence, more or less fair. I can remember at one point at university when the novel was brought up, someone criticised Mary Boleyn and said that in reality she had been a bedhopping slut, or something equally un-PC, and a girl in the room responded, ‘Well, Anne wasn’t exactly much better, was she?’

The novel’s portrayal of Anne as promiscuous, immoral and thoroughly nasty, I think, is what most people came away from TOBG assuming must have been more or less true….and Philippa Gregory’s assertion that she only “filled in the gaps” when the historical record couldn’t provide the info she needed, implicitly led people to believe that everything in the book was either based on fact or was supposition that occurred only when the fact was absent. Many, if not most, of Anne Boleyn’s actions in TOBG bear little or no relation to what we know about the historical Anne’s. Her personality in TOBG appears to be based on the letters of Anne’s sworn enemies. But people find it impossible or improbable that a novelist would claim historical credibility but would then make up SO much about one of the most famous women in British history.

Even members of my Anne Boleyn facebook book page—unusually well-educated in things Tudor—frequently admit that before they began to delve deeper into the history, Philippa Gregory was their authority:

“I completely took TOBG as fact when first reading it in tenth grade! I had no real background knowledge on Anne before reading it, so I took what the book said as fact, especially after reading the author’s note. Ms. Gregory is a very good and CONVINCING author, and it took me reading some other books afterwards to “Detox” Gregory’s Anne from my mind! It really taught me not to take historical fiction at face value.”

This fan became “detoxed.” Others, however, do not. Her most ardent fans do not distinguish between well-researched trivia of the sort that can give you an advantage in board games and the lively—and perhaps “humanizing” but inaccurate—“facts” about what the characters said and did. Neither, it appears, does Gregory, who seems to believe that knowledge about manners, dress, food, or the bad breath of the pre-toothpaste Tudors is enough to keep her novels “grounded in historical fact”.

The seductions of those details have become even more acute in our media-dominated, digitally enhanced era in which people are being cultural trained to have difficulty distinguishing between created “realities” and the real thing. If the created reality is vivid and convincing enough (whether it is a flawless, computer-generated complexion, or a “spin” on events) it carries authority—and that’s the way advertisers and politicians want it. The movies, which are often extremely attentive to historical details, creating a highly realistic texture for the scaffolding surrounding the actions of the characters, make it even harder for audiences to draw the line. Directors, who are after all focused on entertaining rather than educating, may not want audiences to draw that line. Thomas Sutcliffe, the director of The Other Boleyn Girl, describes Peter Morton as “brilliant at side-stepping the usual shrieking reflex of anxiety about mixing fantasy and truth.”

The novelists I interviewed would agree with Morton that too much “anxiety” about the fact/fiction divide would make the work of historical fiction impossible. Margaret George laughingly told me about overhearing someone say, about her Autobiography of Henry VIII, “This is just a lie! Henry VIII never wrote an autobiography!” But George also expressed concern that in an age when most people get their history from TV and movies, we are losing our collective sense of “what really happened.”

But for thoughtful creators of fiction (whether written or cinematic) “shrieking anxiety” and “anything goes” are not the only alternatives. There’s the responsible middle-ground of recognition that there is an unavoidable tension between the demands of history and the requirements of fiction. As Hilary Mantel put it:

You have to think what you owe to history. But you also have to think what you owe to the novel form. Your readers expect a story. And they don’t want it to be two-dimensional, barely dramatized. So (and this is queasy ground) you have to create interiority for your characters. Your chances of guessing their thoughts are slim or none; and yet there is no reality left, against which to measure your failure.

Fiction is commonly more persuasive than history texts. After Wolf Hall was published, I was constantly being asked ‘Was Thomas More really like that? We thought he was a really nice man!’ I could only answer, ‘I am trying to describe how he might have appeared if you were standing in the shoes of Thomas Cromwell: who, incidentally, did not dislike him.’ But of course what I was really up against was A Man for All Seasons: the older fiction having accreted authority, just by being around for two generations. When I say to people, ‘Do you really think More was a 1960s liberal?’ they laugh. ‘Of course not.’ But (again, for the sake of honesty) you constantly have to weaken your own case, by pointing out to people that all historical fiction is really contemporary fiction; you write out of your own time.

[This quote comes from a personal interview with Mantel that I conducted with her while she was writing Wolf Hall. As I’ve discussed in later pieces, she went on to forget—or ignore—some of her own guidelines here. But that’s for another posting!]

P.S. Let me know in my chat room (or a comment here) if you’d be interested my my posting that full interview with Mantel, which thus far has only been published on my website

THE OTHER BOLEYN GIRL: A FACT-CHECKER

[1] Jonathan Jones, in The Guardian. But this is nothing new. In the acclaimed PBS series on Henry as well as Anne of the Thousand Days movie, Anne is never seen reading a book, let alone conversing with Henry—as the actual Anne often did—about the religious debates of the day. Her role in Henry’s break from Rome is purely as the tantalizing object of his desire, his history-launching Helen, for whom he was willing to defy the pope, suffer excommunication, have old friends like More executed, and create a poisonous schism in his kingdom. One of the innovations of The Tudors is its break with this convention, largely due to the intervention of Natalie Dormer.

I was a costume assistant and set person all through high school and college. "Anne of the Thousand Days" and "a Man for All Seasons" were two I worked on while in high school. At that age, being exposed to even that level of history, and being able to compare the plots, was pretty advanced for a high schooler.

Now I am wondering how Shakespeare was able to research all those kings.