Lessons of the Pit Bull: “Breed” as Other

October is Pitbull Awareness Month. So I thought I’d take a break from my Election Watch to repost a stack I did back in April.

This morning I had a nightmare in the back-to-sleep hour between 4:30 and 5:30 when I force myself to get more time in, and when, apparently, my unconscious likes to bubble up. I’d spent the week reading about Pit Bulls, but I hadn’t realized just how much my research, done as antisemitic protests flourished across college campuses (several of which I had spoken at in the past when being Jewish was just one, and mostly unnoticed, part of my identity) had stirred up unexpected associations. I thought I was writing this piece for Piper and Scout, my two Pitties, and all those Facebook friends whose Pit Bulls are adored and adoring members of their families. My dream told me more.

I had gone to sleep hearing news of more demonstrations. In my mind as well was a line from a series I’m watching called “We Were the Lucky Ones,” based on the novel by Georgia Hunter and informed by her own ancestors’ experiences as a Polish-Jewish family during the years of Hitler’s rise, occupation, and eventual establishing of death camps. At one point, Halina (Joey King), the most resourceful of the siblings, gives sister-in-law Mila (played by Israeli actress Hadas Yaron) instructions in how to pass as gentile. It’s not so hard, she says. “They don’t even know what a Jew looks like! Why do you think they make us wear a yellow star?”

In my dream, I was with my youngest dog Scout, looking out the window waiting for pizza to arrive. I saw the car, but no delivery was at my door. Puzzled, I opened the door and saw that the delivery-man—a young, brown-skinned guy of indeterminate ethnicity—had mistakenly gone upstairs to a different apartment. (Present-day, I actually live in what we enviously used to call a “one-family” house, when my family occupied a walk-up tenement above a kosher butcher-shop in “inner-city” Newark.) When the pizza-guy saw me open the lower-floor door to my apartment with Scout at my side, he screamed and threw two large pizza boxes at me and ran. I went to some kind of outdoor porch and tried to explain what a sweet doggie Scout was but he wasn’t having any of it. My lovely little Staffordshire Terrier: nothing but a dangerously aggressive “pit bull” to the pizza guy. It was impossible to convince him otherwise.

My apartment, in the dream, was in ghetto-like neighborhood, much like the one I grew up in. The apartment itself was dark, much like the apartments in the TV series—apartments from which the family fled, dispersing in search of safety.

In non-dream life, I’d been stalling with research, stewing about actually writing the piece. I had imagined angry commenters with horrible tales of maulings and fatalities blamed on the genetics of the “breed.” I imagined personal injury lawyers with similar tales, defending their ghastly websites on which Pit Bulls appear as hounds from hell. I knew I’d be stepping into people’s personal pain and fear, and didn’t want to seem dismissive. I’m not dismissive. But I also know that when a terrible personal experience collides with embedded stereotypes, reason rarely gets very far—and unreason can lead to the most horrific of consequences.

I woke up from my dream remembering a particular photo from my research into dog “breeds.” It had so horrified me that I had to zip past it on my kindle. It was a pile of euthanized pit bulls, thrown one on top of the other, dumped like garbage into a shoveled out ditch.

That’s what happens when “breed bans” shut family dogs out of apartments or pick up “strays,” placing them in kennels that won’t or can’t adopt them out. You think they are living on some special Pit Bull farm?

And a lot of the time, they aren’t even Pit Bulls.

**********************

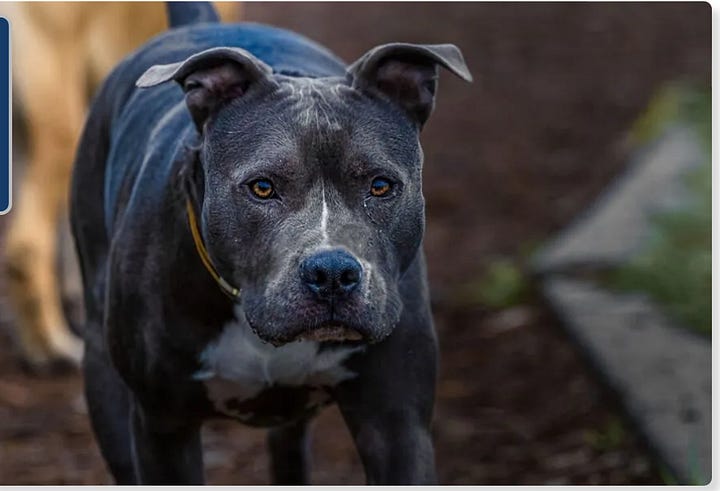

Actually, as you can see from the photos at the end of this piece, there is no one way a Pit Bull “looks.” And there’s no way of knowing, just from looks, what a doggie’s DNA consists of. They don’t wear armbands. And although four “pure” pedigree types still exist, descended from the original matings, in the 1800’s, of Bulldogs and Terriers, most “Pit Bulls” are actually genetic mixes that largely get identified (by neighbors, the police, and even most vets) by looks.

Looks can, of course be deceiving. Anyone who has had a genetic analysis done for a mixed-breed doggie knows how surprising the results can be. Bronwen Dickey, who has written the definitive work on Pit Bulls, reports on several studies that attest to the frequent dissonance between how a dog “looks” and its genetic mix. In one, short video clips of twenty mixed-breed dogs were presented to 900 subjects who worked in dog-related jobs, including veterinarians, trainers, animal control officers, shelter workers, and groomers, who were then asked to identify which breeds were present in which dog. For only seven of the twenty dogs did more than half of the respondents agree on the most prominent breed. And “Interestingly, the predominant breed they chose did not show up at all in the DNA of three of those seven animals. Subsequent research confirmed this pattern. After looking at photographs of 120 mixed-breed dogs, shelter workers mislabeled 55 as being "pit bull mixes," while missing 5 that actually were.

Yet, as one fierce advocate of PB bans put it when asked how to identify a Pit Bull: “Here’s how you do that. If someone thinks it is, it is. If you can’t prove it isn’t, then it is.”

My own first encounter with what I assumed was a Pit Bull was on a remote countryside road in North Carolina. I had won a fellowship at UNC Chapel Hill, and had the fantasy that when I wasn’t at the university, I’d be cozily typing away in a country cottage, my collie Natalia by my side. And maybe some burly gardener tending my weeds. I said fantasy. The reality: a long drive for cigarettes, strange species of menacing-looking flora that had overtaken the garden and invited many biting insects to join them, and a helpful neighbor who warned me of a “crazy man” in the vicinity who’d hid out in someone’s closet and had been seen loitering around my house. Within days I was looking for a rental in Chapel Hill.

While waiting for my rental to be available, I took my collie on walks down the road that led from my house through the “neighborhood.” On one of those walks, a woman came to her front door, letting out a dog who raced across the grass, heading straight for me and Natalia. It looked like a Pit Bull to me, and I assumed he was heading to tear Natalia—and possibly me—to pieces. “Call your dog back!!!!” I screamed to the woman, and she did so.

Was her dog actually a Pit Bull? I don’t know; I just assumed, on what basis I don’t remember. Maybe it was its looks; maybe it was its focused intent (to kill us, I figured then, but I now know my Scout runs to strangers just as fast and with as much intensity as that woman’s dog—with the goal of getting some love. It’s her main job in life—she even likes getting injections at the vet because they stroke her while doing it.) But maybe, too—no, not just maybe, for sure—it was the obvious rural poverty (urban poverty was familiar to me and didn’t frighten me) of the woman that my lizard brain immediately associated with an “uncivilized,” uneducated, brutish dog. (In fact, her dog was so well-trained he turned around at her command, something my own dogs have never learned to do.)

********************

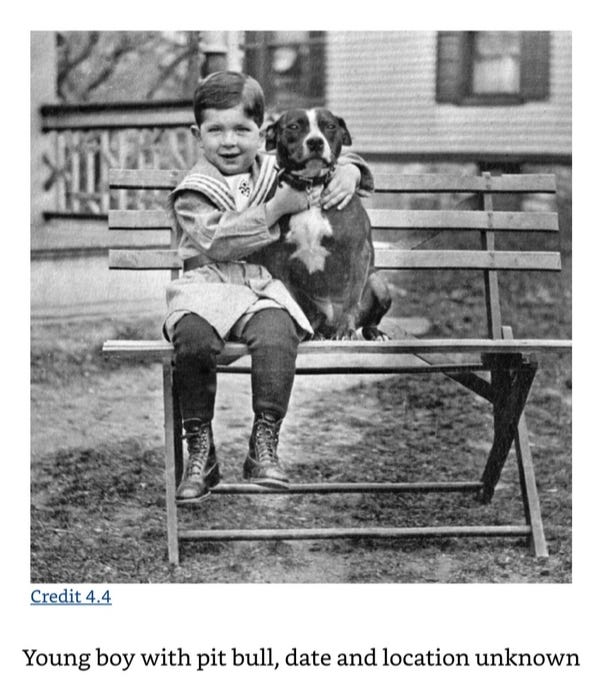

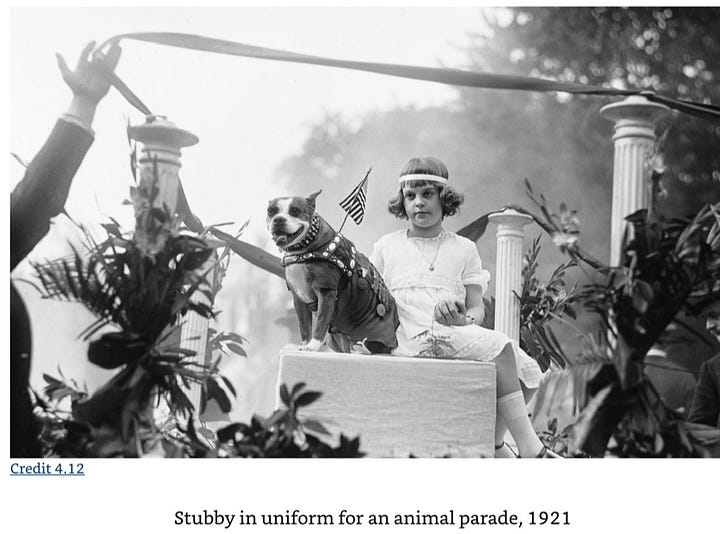

Classism has always been part of canine history. For some time in America, however, it worked in the Pit Bull’s favor, as the PB was associated, not with the undisciplined vices of the “lower” classes but the pluck, courage, and tenacity of the “average working-class Joe.” As such the PB was a frequent mascot for sports teams and soldiers—and a popular family dog: “During the 19th century, pit bulls were owned and enjoyed as house pets by people from all walks of life, but especially those in the working class. Into the 20th century, they became a symbol of the resilience of the American people - the valorized "everyman" that was centered in popular culture during that time.”

What changed?

For one thing, even as the PB remained popular among “all classes” during the first decades of the 20th century, evolutionary theory had laid the scientific groundwork both for the “elite” breeding that branded the all-purpose mixed-dog as an inferior “mutt” and at the same time, got genetic determinists specifying the qualities that characterized the “breed.” How could the PB be a “mutt” and a unitary “breed” at the same time? Don’t ask for consistency when science is pressed into the service of ideology.

Unsurprisingly, the fashion for “pure” pedigree dogs coincided with the development of theories about the genetic inferiority of “lesser” races:

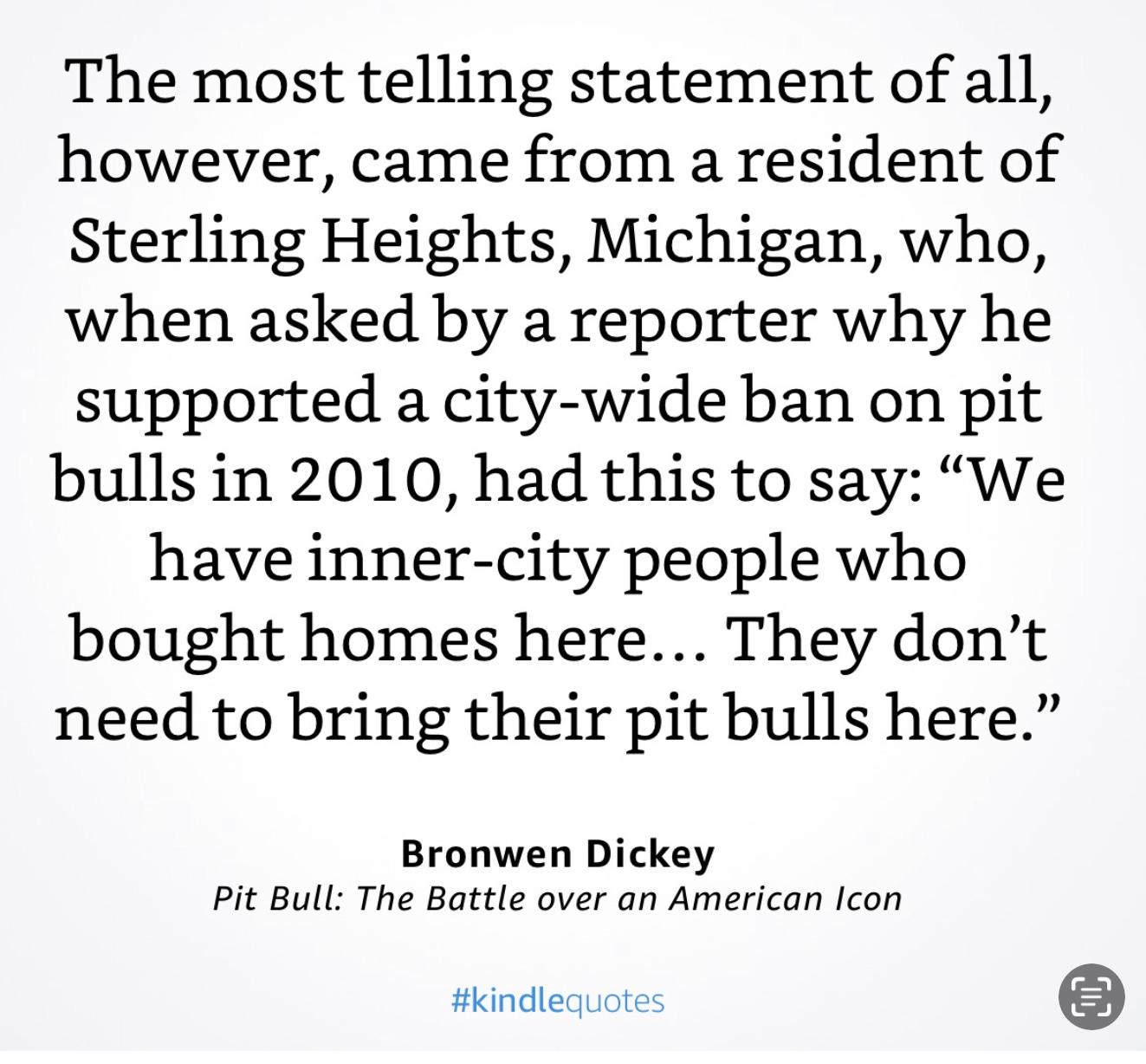

The history of eugenics and the history of animal breeding were tightly interwoven from the start. Though drastically different in scale and moral consequences, both fields were prone to the same cognitive errors—namely, a fanatical devotion to blood purity. Their language and philosophies also cross-pollinated one another heavily. The executive secretary for the American Eugenics Society (AES) during the 1920s was a prominent veterinarian and bloodhound breeder named Leon Fradley Whitney, who at one time penned a pet column for Good Housekeeping and wrote a number of dog-breeding manuals for the general public. During his tenure at the AES, Whitney heartily endorsed “Fitter Families for Future Firesides,” in which humans were physically evaluated like livestock in formal “shows” held at Midwest county fairs. His most famous work, The Case for Sterilization (1934), applauded Hitler’s efforts to establish a “master race” in Germany and was eventually used to justify mandatory sterilization laws in the United States. More than sixty-two thousand poor, sick, or mentally ill Americans were forcibly sterilized under such laws, and most of them were women from racial or ethnic minorities." (from "Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon" by Bronwen Dickey)

Add to this the growing popularity of the Pit Bull among the urban (read: Black) poor, who couldn’t afford fancy pedigreed dogs and were attracted by the PB’s historical reputation as a tough, protective fighting dog—their pets often decked out in spiked collars and other “warrior” accessories—and you have the perfect recipe for the identification of the Pit Bull with its owners, both defined by their different—and dangerous—“otherness.” In 1987, Dale Dunning, then the executive director of the Arizona Humane Society described the Pit Bull as “more dangerous than a loaded .357 magnum.” As for “those people who buy a pit bull”:

They are getting a bomb without a detonator, because you cannot predict what will trigger an “explosion.” Most dogs give adequate warning of an impending attack and then bite and retreat. A pit bull, on the other hand, typically gives no such warning of an attack… Other breeds fight to protect territory, food, or mates. A pit bull fights because it has been bred to fight. In short, it is a four-legged fighting machine and a killer. Dunning co-authored an “educational” pamphlet that pushed these statements into the realm of utter anatomical impossibility, alleging, “[ Pit bulls] chew with their back teeth while holding with their front teeth.

(Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon by Bronwen Dickey)

The broad genetic tent covering the PB’s history holds everything from dogs bred specifically to be more aggressive in the “pit” to those that have among the gentlest, most loving personalities (increasingly the case over the past century1—which in large part explains the resurgence of the PB as a family dog widely celebrated in videos on Facebook and Instagram) and everything in between (in other words, a regular dog rather than a hound from hell.) And despite years genomic analysis, “no researcher has yet located an ‘aggression gene’ or a set of aggression genes.” Yet the notion that there is a singular “breed,”characterized by extreme aggression, with a “dogfighting nature” and the appropriate equipment to serve that nature (including ill-founded myths about the Pit Bull’s locking jaws) is still exploited by personal injury law firms encouraging the victims of dog bites to seek their services.

Pictures of glaring, vicious, teeth-baring Pit Bulls are all over these websites, while other breeds are shown sweetly cozy or harmlessly side-by-side with children:

My own personal experience with dogs lent irony to the above photographs from a personal injury website as the only dogs I’ve owned that drew blood from humans or other dogs were my Jack Russell Terrier Vinnie and a Golden Retriever named Prouncer. Vinnie didn’t like male strangers or female strangers who looked or walked like men (according to his politically incorrect gender attributions), but we knew it, so we made sure to have him gated and workers warned not to try to pet him when they first met him. One, however, just wouldn’t believe the cute little fella could possibly resist him, and wound up shaking his arm, trying to detach Vinnie from his hand. Vinnie was quarantined for that one, because the man reported him. But most bites, when they come from breeds that aren’t branded as “aggressive,” don’t even get reported. That was the case with Prouncer, a sweet puppy who became unexpectedly territorial as she matured, and although they had lived together peacefully for months, damn near killed my border collie Jenny. (We tried several trainers and methods, but nothing worked, and we ultimately found her a home without other dogs.)

All dogs are capable of causing serious injury. Yet many people believe that a breed like the Golden Retriever is much safer as a pet than a Pit Bull. “Try telling that,” Bronwen Dickey writes, “to the parents of Aiden McGrew, a two-month-old baby killed by his family’s “golden retriever/ Labrador mix” in South Carolina in 2012. Or Kimberly Demaree, a woman from Chesterfield, Virginia, who was hospitalized after being severely injured by a golden retriever that jumped its five-foot-high fence in 2013. Or Kelly Lawrence, who sustained more than seventy puncture wounds and a cracked wrist when her golden retriever latched onto her arm and shook it “like a rag doll” in 2014.”

The personal injury websites will cite statistics on the greater frequency of Pit Bull dog bites, but they don’t mention the difficulties I described earlier in identifying which of the dogs they’ve included in their stats as “Pit Bulls” actually are PB’s. They also usually neglect to point out how infrequently the “nips” (and worse) of less “dangerous” breeds are reported (particularly if they are family dogs.)

Yes, an attack by a muscular Pit Bull would more likely be fatal than that of a Jack Russell Terrier. Nonetheless, “Forty-four different breeds (including the dachshund, the West Highland terrier, and the Jack Russell terrier) have been linked to human deaths since 1979, the year the CDC began tracking fatalities by breed. If ‘fighting genes’ had prompted pit bulls to kill humans, then what explained the deaths caused by German shepherds, Labrador retrievers, Chesapeake Bay retrievers, Siberian huskies, Brittany spaniels, Newfoundlands, coonhounds, collies, and sheepdogs, among others?”

Moreover, despite the stats provided by personal injury firms’ websites, there’s actually no way of determining how “dangerous” any breed is, because we don’t have numbers on how many members of each breed there are in the American dog population. Only a fraction of dogs are registered. Many are homeless. Not all dogs, particularly rural dogs, whose owners may know enough about worming and vaccinating animals themselves—are taken to vets. So there can be no way to calculate “relative risk” by breed.

“What’s more, there were far too many potentially confounding variables in each DBRF (Dog Bite Related Fatality) case that could not be controlled for. In order to determine the relative “dangerousness” of a population of dogs in a scientifically credible way, you would have to know how the dogs in that group were bred, raised, socialized, trained, fed, handled, and housed. You would also have to study the dogs’ neurological makeup, serotonin levels, hormonal balance, and general health, then take into consideration the behavior of the humans in the dogs’ immediate environment. Until the role of those variables could be determined, it wouldn’t matter if all dog bite deaths were caused by purebred APBTs or AmStaffs; the total number of incidents would simply be too small to be significant.” (Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon by Bronwen Dickey)

Happily—though you couldn’t tell from the lurid media accounts—dog attack fatalities—taken in total, including all breeds—are rare. In 2017, DogsBite.org reported a total of 392 deaths from 2005 through 2016. That’s over ten years. As horrible as the individual stories are, that means that (in 2017, at least) you were more likely to die from a fall, choking, an accidental fire arm discharge, or a hornet, wasp, or bee sting than from a dog attack by any breed. The same study reported that the American Veterinary Medical Association, after an in-depth literature review to analyze existing studies on dog bites and serious injuries, found that “there is no single breed that stands out as the most dangerous.” Rather, “studies indicate breed is not a dependable marker or predictor of dangerous behavior in dogs. Better and more reliable indicators include owner behavior, training, sex, neuter status, dog's location (urban vs. rural)”, whether the dog has spent its life chained or tied up, been abused, and/or been involved in dog fights.

********************

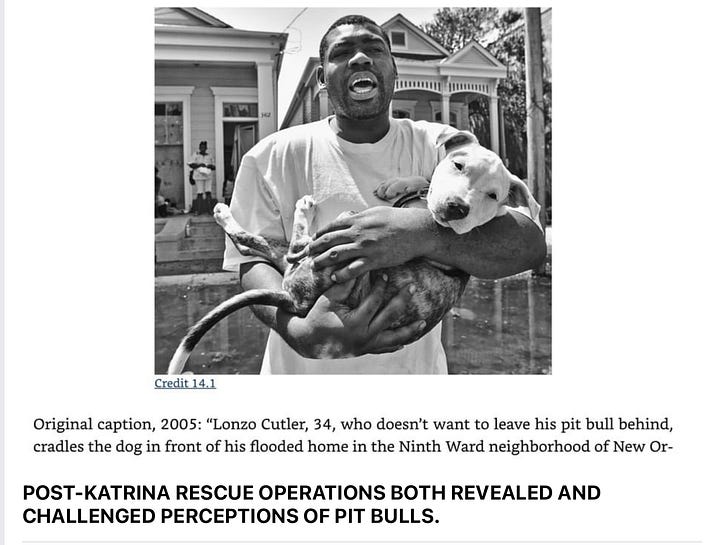

After Hurricane Katrina, the flooded streets were full of Pit Bulls, paddling through the water and stranded on rooftops with their owners, many of whom refused to be rescued without their dogs. The dogs were met with expectations that distorted perceptions and made rescuers wary. But unlike their Black owners, whose actions were misreported for weeks in newspapers, “confirming” every racist and classist assumption about the poor people forced to take refuge in the Superdome (Mayor Ray Nagin: “hooligans killing people, raping people”; Police Chief Eddie Compass: “little babies were getting raped” etc.), once the rescuers met their dogs, expectations were challenged.

I first saw a picture of our pit bull mix Piper on a website listing rescue dogs for adoption. At that time, she was called “Susie Q”—despite which my daughter immediately singled her out. “A pit bull?” I questioned. “YES,” Cassie answered emphatically. When taken to “Susie Q” at the shelter, she was huddled in one cage with another, more visibly pit-bull-looking dog. We were told they’d been there for awhile.

“Susie Q” was led from her cage to the backyard of the shelter, where Cassie, Edward and I waited to meet her. She immediately bounded over to us, tail wagging and butt wiggling, ran to Edward and sat down as if awaiting instruction (a smart choice, as he was the most skeptical about adding another dog to our lives—although he now says “She had me at her picture”.) “I know you’re thinking about taking me home,” she seemed to be saying, “just tell me what to do next, and I’m yours.” “She was such a good little soldier, sitting down like that,” Edward recalls. “I found it terribly touching.” We all felt she was fated to be a member of our family. (As we left, we were told that the dog she’d been caged with would stand a much better chance of adoption now that he was alone. And he was—within days. Relief.)

Pit Bull families are full of stories about their dog’s boundless enthusiasm for life—and capacity to love. My own favorite story is about Piper. Whenever I had my writing class over my house, all my dogs would hang around, hoping for dropped bits of pita bread and empty laps. In one such class, the students were reading aloud from their memoirs. There were several stories of abuse—actually many, far, far too many—but most of the students offered them without visible emotion. One student, however, perched on an armchair way across the room from Piper, who was semi-dozing in front of the fireplace, had started to tremble while reading her story. It was barely noticeable, but Piper’s head shot up, her attention suddenly focused. Then, seconds before my student’s tears actually started to flow, that sweet dog had galloped across several bodies sitting on the floor (leaving bruises I’m sure) and jumped up the arm of the chair to lick my student’s face. What had she sensed from way across the room? And why did she feel her services were needed? My other dogs were oblivious, their attention riveted on the food that had been jarred loose from paper plates during Piper’s run.

I’ve adored all my dogs but after we adopted Piper I began to realize that there had been something a bit remote about all of them. it’s difficult to describe, as they were all devoted darlings who would follow me around the house, and I mourned deeply when they died. But they didn’t crave closeness and kisses the way Piper did, and I never felt that their eyes looked straight into my soul, as if trying to figure out what I needed (rather than what they could do to get what they needed.) They appreciated my love, but when they twitched and yelped in their sleep I felt they were dreaming of a different, freer life. Of course they were! They were dogs! But Piper emanated the sense that in this house with these humans was exactly where she wanted to be. She lived for snuggles and kisses as avidly as for treats. Scout, our nearly 3-year old American Staffordshire Terrier is even more that way.

I’m not going to draw any breed-ish conclusions from my two pitties. (If you don’t like that diminutive, think about the connotations of “pit” and “bull” and perhaps you’ll appreciate the need for a different name.)2 Instead, I leave you with a gallery of photos posted by Facebook friends who knew I was writing this piece and shared their doggies with me. (If I’ve somehow missed your photo, please do include in the comments.)

According to the American Temperament Tests Society, many of the top breeds often thought of as dangerous often consistently perform well in their testing. Even those considered dangerous or aggressive by most people often perform incredibly well.

The Temperament Test observes and measures temperament indicators such as stability, friendliness, protectiveness, shyness, and aggressiveness.

87.4% of the 931 American Pit Bull Terriers that tested passed the test. Their results are similar to Collies (80.8% of 896 dogs), German Shepherds (85.3% of 3383), and even higher than Golden Retrievers (85.6% of 813). (14)

There are those that celebrate the “bull” part, and have bred dogs to accentuate it. It’s usually not good for the health of the dog, and hasn’t helped the Pit Bull’s reputation.

I missed this back in April. Thank you for reposting. Yay for pitties!❤️

No bad dogs. Just bad owners. And sometimes bad breeders. A wonderful essay. Thank you for this.