Not Just Barbie’s Fault

Even before the doll came on the market, girls were being bombarded—and still are—with unrealistic and punishing images of feminine “perfection.”

I’ve been writing about cultural imagery, eating disorders, our cultural horror of fat, the global spread of eating problems, and the meaning of the thin body for over thirty years. My first piece on eating disorders was published in 1985; it was among the very first discussions to go beyond medical explanations to consider the role of images, gender roles, and consumer culture, and was following by many articles and three books on the body in historical and contemporary context.

Feminists have been discussing Barbie for a long time, and the perspective of Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie” owes a great deal to those discussions, which explored both the negative and the positive place of the doll in girl culture. This piece, unlike my most recent two pieces, is not about the movie or about the doll (too many people have conflated the two, in my opinion) but draws from my published work to argue how complicated body-image problems among girls are, and why they can’t simply be attributed to Barbie (the doll)—and certainly not to the movie!

I’ll start with some memoir:

Fat Susie Klein

Until my younger sister was born, I was the baby of our family. Then, when I was four, she was brought into the house and I began to eat. First, I’m told (it may be a family myth), it was her toe, which they say I tried to bite off the first night she came home. Then it was chunks of white bread, gauged from the middle of the loaf, compressed into chewy lumps and dunked in mustard. I had to do my binging when no one was home, though, as my father himself in those days was fat and I became his shame-surrogate — not only for over-eating but for failure to “stick to” anything: diets, learning to swim, finishing school assignments. “You’re just like your Aunt Etta,” he’d say scornfully, disgust twisting his mouth; she was even fatter than he was and branded as the “lazy one” among his siblings.

I got fatter and fatter, and more and more afraid and ashamed of my body. I couldn’t climb the ropes or jump over the horse in gym class, and the gym teacher shook his head scornfully and occasionally called me names. I dreaded going to school and each morning, pretending sickness, I would hold the thermometer near the radiator. Once I went too far and it burst, causing shape-shifting droplets of mercury to spray all over the linoleum floor. They were fascinating to look at as they scurried this way and that, but I’d heard mercury was poisonous, so I had to call my mother in. She let me stay home anyway; suffering from depression herself, she couldn’t deal with my sobbing when forced to go to school.

When my half-brother got married, they took me to Lane Bryant to get a dress. It was a hideous thing, with an enormous floral bloom right in the middle of my chest, I suppose to distract from the body that wore it. Although I was approaching adolescence, they made me march in the “children’s parade”; I was easily the biggest marcher, my head down and cheeks burning, and when the wedding photos were shown around, I begged my parents to throw away the ones in which I appeared. Of course, they didn’t — but when I finally got my own hands on copies, I cut myself out of all of them.

At some point, I decided that if I was going to be at all happy in this life, I needed to remake myself. So the summer before high school, I began the endless cycle of dieting — losing weight — gaining weight — dieting — gaining weight that has been a constant in my life. After a summer of cottage cheese and hamburger patties without the bun, I started high school on the hottest day of the year in a form-fitting rust-colored wool dress that I had chosen for the reveal and wasn’t going to give up no matter how sweaty and scratchy it felt.

Since then, there have been long periods in which I was relatively slender, and I never again let myself approach a weight which would allow me to be classified, as I had been in childhood, as fat. Men found me attractive, and — as for many women with body-shame — their sexual attention became a drug. It offered proof that fat little Susie Klein was no longer in the room, and dulled the fact that no matter how slim I was, I still hated my thick calves and ankles. When a lover held my legs up and kissed them all the way from chunky foot to hefty thighs, gratitude flooded me and I felt reborn.

Once you have been fat, however, the shame never really leaves you. When after menopause I began to slowly gain 10–20–30–40–50 lbs., it became a horror, once again, to look full-body in the mirror. The disgust that I felt as a child was back with me again, only this time accompanied by the uncanny body-changes that aging brings. Seeing an overweight body was familiar. My body in my 70’s is a stranger. I’d always had a defined waist; now it’s virtually gone. My skin was smooth; now it’s crinkly. My boobs were full and shapely, but never huge; now I wear a bigger size bra than I’d ever imagined. At 76, too, getting my weight down has become a necessity for the control of blood pressure and avoidance of diabetes. But I know that little Susie Klein is still there as I step on the scale. She knows that my pleasure and pride at pounds recently lost are not just about concerns for my health and longevity.

I step off the scale and walk into the kitchen where my husband is making breakfast. “Can you tell?” I ask. “I can!” he answers. “Look,” I say, and show him how the long hoodie that once hugged my hips is now slightly loose. He smiles, and whether or not he actually notices, tells me he does.

Fat little Susie Klein, for that moment at least, seems vanquished. But Susan Bordo, 72-year-old author and teacher, who wrote an influential book about body-image with only one line in it about her own struggle with weight, knows she will forever be with me.

(Based on “I Wrote a Famous Book About Body-Hating and Never Mentioned my Own. Let me Correct That Now…” in Medium, December 2, 2020)

Walt Disney Made Me Diet

I was born too early for Barbie to have any impact on my self-image.

I blame Walt Disney.

For before we became compulsive consumers of body-perfecting products and services, we first had to learn that the body is a commodity, capable of being shaped to resemble idealized images. And in my life as a female body, the Mouseketeers were a turning point.

The Mickey Mouse Club, which premiered in 1955 when I was probably at the nadir of self-shame, found an especially ripe target in me. Does “target” seem excessively conspiratorial? The fact is that Walt very consciously set out to exploit the potential of baby boomers as consumers, as did all the kids’ shows. They had a powerful sales tool: “Most of the children’s-show hosts were hucksters in the guise of father figures. There was the friendly hunter (Buffalo Bill) or a friendly museum watchman (Captain Kangaroo) That combination of warmth and authority . . . was a powerhouse sales tool. If Dad says Wonder Bread is good for you, then it must be true.”

From the beginning, The Mickey Mouse Club was a bonanza for merchandisers.The show featured more ads than any other at the time—twenty-two per episode. And Disney was (and “Disney, Inc.” still is) a master at commodifying entertainment, from Davy Crockett hats and Spin and Marty books to tie-ins with Mattel toys. In 1955, when Club premiered, Mattel had annual sales of four million dollars. That Christmas, it began to advertise on Mickey Mouse Club; within a few years sales topped thirty-five million.

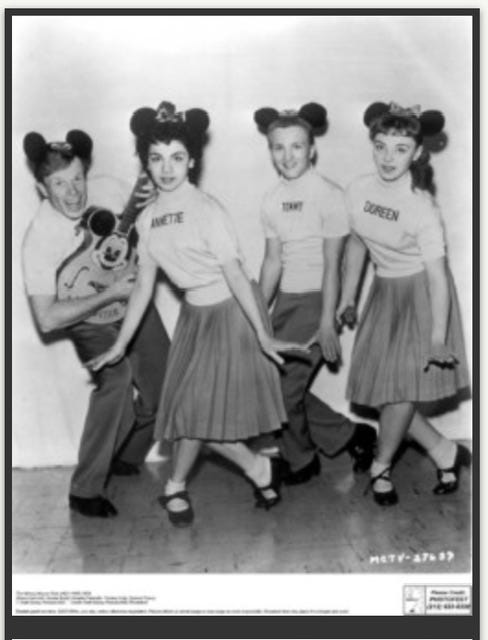

A huge source of revenue came from the promotion of mini-stars whose every fashion choice and hobby, featured on the pages of teen magazines, afforded opportunities to sell, sell, sell. At the beginning of each show, the chosen ones proudly introduced themselves: “Annette!” “Darlene!” “Cubby!” “Bobby!” Mouseketeer hats? If you were born in the years between 1946 and 1952 it’s highly likely you had one.

But the most enviable Mouseketeer for me—Annette Funicello—didn’t just have a hat with ears and a cute little plaid pleated skirt. She also had breasts—at first modest, but growing more prominent with every season, eliciting both adolescent lust and snickers from the boys and teaching girls, as Susan Douglas remarks, that whether desired or demeaned, they were defined by their bodies.

Fashion has always been a harsh dictator. But in previous twentieth-century periods, the dissemination of images was limited to high fashion magazines or, for those who couldn’t afford Chanel, sketches in Sears Roebuck catalogues. The post-war period changed all that. There was a new consumer—eventually to be called baby boomers, first generation to constitute a distinctive “youth market”—and there were new media (teenage-geared movies, magazines, television shows) to pump up our desire, our desperation to look like the teen celebrities (and a little later on, the models) that seemed so perfect to us. Photo spreads designed specifically for teens now began to dictate our fantasies and expectations more than books. Goodbye Jo March, hello Gidget.

The most desirable teenage body in the early Sixties, when a return to domesticity was still winning out over the cool, androgynous look emerging from Carnaby Street, was a version of the hourglass. Annette had a tiny waist and perky breasts, as did Sandra Dee, as did Connie Stevens and teenage Elizabeth Taylor; it was a feature that was accentuated by the belted shirtwaist dresses favored in those days. They were more zaftig real-life Barbies, and I did everything I could to get their look: stuffed my bra with tissue paper, even wore a belt under my one-piece swim suit to cinch my waist in. I’m sure it looked absurd and fooled no-one and I’m glad I have no surviving pictures.

But that was the early sixties. Within a few years, that particular feminine mystique was challenged, both politically and aesthetically, and “swinging London” had given us a new, decidedly non-domestic ideal. Skinny, leggy, and flat chested had always been a high-fashion look. But we knew there was a difference between a Vogue model and what was expected from us ordinary girls. In the mid-sixties, all that changed. Being a mini-version of ones mom was not cool; our imaginations were caught by the unencumbered, boyish, slightly awkward allure of Twiggy, Penelope Tree, Edie Sedgwick. That coltish body and all it signified caught on big time, and by the time I started teaching college in the 1980’s, my female students were writing in their journals of despising their “thunder thighs,” being afraid of food (“If I eat one cookie, I won’t be able to stop”) and measuring their worth by the numbers on their scales.

As for me, after my summer of cottage cheese before I entered high school, for a while, I looked “right.” But by the time I was a junior in high school, that changed. While I could approximate the curvy idea of the Fifties through diet and the right kind of bra, my 5-foot 2-inch, big-booty body—shaped by centuries of Eastern European genes—made it impossible for me to look anything like a Twiggy, or even a Peggy Lipton of The Mod Squad. To add insult to injury, my bust—the one feature of my body that had satisfied the “mammary madness” of the 1950s—was now not just out of fashion, but an embarrassing signifier of an out-of-date ideal of femininity. The hourglass figure had been valued as the symbolic embodiment of a domestic (male-sexualized, reproductive) destiny. The flat-chested, lanky look, in contrast, made you a cool girl who had the sexual ease and the social freedom that I craved. As for my big booty, I was too old to personally benefit, but not too old to appreciate it when hip-hop took its revenge.

(From TV, Bloomsbury Press, 2021)

Never Just Pictures (1997)

How can mere images be so powerful? For one thing, they are never “just pictures,” as the fashion magazines continually maintain (disingenuously) in their own defense. They speak to young people not just about how to be beautiful but also about how to become what the dominant culture admires, values, rewards. They tell them how to be cool, “get it together,” overcome their shame.

For the most part, designers and fashion magazine editors have been in denial about the role played by cultural images in the spread of eating and body image problems. As designer Josie Natori argued (in a Harper's Bazaar magazine article specifically "answering" feminists), anyone ought to know that "fashion is not about reality. It's about ideas and vision” (1993: 78). Nike, in an ad for its running shoes, makes a similar, self-exonerating argument:

A magazine is not a mirror. Have you ever seen anyone in a magazine who looked even vaguely like you looking back? Most magazines are made to sell us a fantasy of what we’re supposed to be. They reflect what society deems to be a standard, however unattainable or realistic that standard is. That doesn’t mean you should cancel your subscription. It means you need to remember that it’s just ink on paper. And that whatever standards you set for yourself for how much you want to weigh. For how much you work out. Or how many times you might it to the gym. Should be your standards. Not someone else’s.

In some ways, of course, Natori and Nike are right. Fashion images are not meant to be a “mirror” of reality, but are an artfully arranged manipulation of visual elements. What neither Natori or Nike acknowledge, however, is that those elements are arranged precisely in order to arouse desire and longing, to make us want to participate in the world they portray. That is their point and the source of their potency, and it's in bad faith for the industry to pretend otherwise.

Here, it is important to recognize that images are not imprinting devices, and the girls and women that respond to them are not passive “dupes”. Rather, the culturally successful image—the one that advertisers and designers reproduce endlessly--carries values and qualities that "hit a nerve” that is already exposed. As such, they are not only or primarily about the desirability or attractiveness of a certain body size and shape, but about how to become what the dominant culture admires, how to "get it together," be safe from pain and hurt.

The message and the “solution” offered by the fat-free body: be aloof rather than desirous, cool rather than hot, blase rather than passionate, and self-contained rather than needy. To girls who have been abused the abolition of “loose” flesh, through diet or exercise, may speak of transcendence or armoring of a too vulnerable female body. For racial and ethnic groups whose morphology—large buttocks, “big” legs--have been marked as foreign, earthy, and primitive, mainstream images may cast the lure of assimilation and acceptance. To girls and women who feel torn apart by the contradictory demands of being both feminine and tough, high-performing but non-threatening to men, sexy-looking but not inviting of unwanted sex, the tightly controlled body may seem a perfect resolution.

When we admire an image, a kind of recognition beyond a mere passive imprinting takes place. We recognize, consciously or unconsciously, that the image carries values and qualities that "hit a nerve" and are not easy to resist.Their power, however, derives from the culture that has generated them and resides not merely "in" the images but in the psyche of the viewer too. When I asked my students why they found Kate Moss so appealing. It took them a while to get past "She's so thin! And so beautiful!" I wanted to know what made her beautiful in their eyes and how her thinness figured into that. Once they began to talk in nonphysical terms, certain themes emerged again and again: She looks like she doesn't need anything or anyone. She's in a world of her own, untouchable. Invulnerable. One of my students, who had been struggling unsuccessfully with her bulimia all semester, nearly moved me to tears with her wistful interpretation. "She looks so cool," she whispered longingly. "Not so needy, like me."

If thinness is a visual code that speaks to young women about the power of being aloof rather than desirous, cool rather than hot, blase rather than passionate, and self-contained rather than needy, fat represents just the opposite-the shame of being too present, too hungry, too overbearing, too needy, overflowing with unsightly desire, or simply "too much." Often the fear of being "too much" will have a strong sexual dimension, an association that is present in the stories of women with anorexia and bulimia, disorders that often arise after episodes of sexual abuse, sexual taunting, or rejection by fathers who are uncomfortable with their daughter's maturation.

The associations of fat, voraciousness, and excessive sexuality are also frequent in the life experiences of fat women:

"Being fat meant that I had uncontrollable desires, that I was voracious. It was a clear danger sign to men: stay away, this woman will eat you up.... Appetite equals sexual appetite; having a sundae is letting go. Eating that cake and ice cream meant I wasn't getting sex, and look how much sex I must need if I had to eat so much to compensate. Since I couldn't control myself around food I wouldn't be able to control myself around men; since no food ever satisfied me, no man ever would. "

But being fat is not a prerequisite for experiencing these equations. While looking through old diaries of mine, I came across an entry that revived disturbing memories for me. It was written during a time when I had been ill and depressed and had consequently lost a great deal of weight. I was thin to the point that I no longer felt I looked very good, and I was withdrawn and anxious most of the time. I wrote:

I've suddenly realized that deep inside me, I am convinced that men will find me more attractive in my diminished state. X's cousin this past week-end mentioned how good I looked, and I felt that he found me attractive. Here's how I was: skinny, no makeup, hair lank and dirty. I remember when I was so depressed that other time, got down to 114 pounds, and could barely do anything;Y wanted to have sex with me all the time.... Here is the way I used to be: robust and Jewish, brainy, forceful, demanding, conscious, conscious, conscious. Now I am so much less, both physically and in terms of assertiveness ... and I'm aware of how drawn men are to me.

Reading this entry was chilling. I had forgotten about those moments when I suddenly realized that some man was attracted to me because I was "less." Remembering those moments, I was reminded of a truth that is hard to face, about the personal price women may pay for increased presence and power in the world, and the personal rewards they receive for holding back, keeping themselves small and tentative.

Anxieties about women as "too much" are also layered with racial and other associations that, contrary to the old clinical cliches, set up black, Jewish, lesbian, and other women who are specially marked in this way for particular shame.

According to the old cliches, those who come from ethnic traditions or live in subcultures that have historically held the fleshy female body in greater regard and that place great stock in the pleasures of cooking, feeding, and eating are "protected" against problems with food and body image.There is an element of truth in this understanding. Certainly, many cultural heritages and communities offer childhood memories (big, beloved female bodies, sensuous feasts), places (the old Italian neighborhood, the lesbian commune kitchen), and cultural resources (ethnic art, woman-centered literature) that seem diametrically in opposition to the idealization of thin—particularly if there’s a history of poverty in which getting food on the table was an achievement.

But each of us also lives within a dominant culture that still often recoils from what we are.We may grow up sharply aware of representing for that dominant culture a certain disgusting excess-of body, fervor, intensity-which needs to be restrained, trained, and, in a word, made more "white." A quote from poet and theorist Adrienne Rich speaks to the bodily dimension of "assimilation":

"Change your name, your accent, your nose; straighten or dye your hair; stay in the closet; pretend the Pilgrims were your fathers; become baptized as a Christian; wear dangerously high heels, and starve yourself to look young, thin, and feminine; don't gesture with your hands.... To assimilate means to give up not only your history but your body, to try to adopt an alien appearance because your own is not good enough, to fear naming yourself lest name be twisted into label."

I include myself here, as a Jewish woman whose body is unlike any of the cultural ideals that have ruled in my lifetime and who has felt my physical "difference" painfully. I have been especially ashamed of the lower half of my body, of my thick peasant legs and calves (for that is indeed how I represented them to myself) and large behind, so different from the aristocratic WASP norm. Because I've somehow felt marked as Jewish by my lower body, I was at first surprised to find that some of my African-American female students felt marked as Black by the same part of their bodies. I remember one student in particular who wrote often in her journal of her "disgusting big black butt." For both of us our shame over our large behinds was associated with feelings not of being too fat but of being "too much," of overflowing with some kind of gross body principle. The distribution of weight in our bodies made us low, closer to earth; this baseness was akin to sexual excess (while at the same time not being sexy at all) and decidedly not feminine.

We didn't pull these associations out of thin air. Racist tracts continually describe Africans and Jews as dirty, animal-like, smelly, and sexually "different" from the white norm. Our body parts have been caricatured and exaggerated in racist cartoons and "scientific" demonstrations of our difference. Much has been made of the (larger or smaller) size of penises, the "odd" morphology of vaginas. In the early nineteenth century Europeans brought a woman from Africa-Saartje Baartman, who came to be known as "The Hottentot Venus"-to display at sideshows and exhibitions as an example of the greater "voluptuousness" and "lascivity" of Africans. Baartman was exhibited as a sexual monstrosity, her prominent parts an indication of the more instinctual, "animal" nature of the black woman's sexuality.

When the female "dark Other" is not being depicted as a sexually voracious primitive, she is represented as fat, asexual, unfeminine, and unnaturally dominant over her family and mate-for example, the Jewish Mother or Mammy. The associations are loaded even more when sexuality enters in. As one woman notes, "As a Fat Jewish Lesbian out in the world I fulfill the stereotype of the loud pushy Jewish mother just by being who I am (even without children)!" The same woman remarks that the culture of the nineties has "brought a new level of fat hatred within many lesbian communities ... [an] overwhelming plethora ofpersonal ads which desire someone fit, slim, attractive, passable, not dykey, athletic, etc."

That "not dykey" and "slim" are bedfellows here is not surprising. An older generation of lesbians who dressed in overalls and let their hips spread in defiance of norms of femininity may be as much an embarrassment to stylish young lesbian as the traditional Jewish mother is to her more assimilated daughters.

A similar desire to disown the "too much" mother, I believe, motivates many young women today in their relation to feminism and to the stereotypes of my generation's feminism which they have grown up with.Young women today, more seemingly "free" and claiming greater public space than was available to us at their age, appear especially concerned to establish with their bodies that, despite the fact that they are competing alongside men, they won't be too much (like their strident, "aggressive," overpolitical feminist mothers). In conversation, they lower their heads and draw in their chests, peeking out from behind their hair, pulling their sleeves over their hands like bashful little girls. They talk in halting baby voices that seem always ready to trail off, lose their place, scatter, giggle, dissolve.They speak in "up talk," ending every sentence with an implied question mark, unable to make a declaration that plants its feet on the ground. They often seem to me to be on the edge of their nerves and on the verge of running away. They apologize profusely for whatever they present of substance, physically or intellectually. And they want desperately to be thin.

(From “Never Just Pictures,” inTwilight Zones: The Hidden Life of Cultural Images from Plato to O.J.

Disordered Consumers

In her memoir, Wasted (1998), Marya Hornbacher succinctly describes the paradox of eating disorders:

An eating disorder is not usually a phase, and it is not necessarily indicative of madness. It is quite maddening, granted, not only for the loved one of the eating disordered person, but also for the person herself. It is, at the most basic level, a bundle of contradictions: a desire for power that strips you of all power. A gesture of strength that divests you of strength. A wish to prove that you need nothing, that you have no human hungers, which turns on itself and becomes a searing need for the hunger itself. It is an attempt to find an identity, but ultimately it strips you of any sense of yourself, save the sorry identity of ‘sick.’ It is a grotesque mockery of cultural standards of beauty that ends up mocking no one more than you. It is a protest against cultural stereotypes of women that in the end makes you seem the weakest, the most needy and neurotic of all women. It is the thing you believe is keeping you safe, alive, contained—and in the end, of course, you find it is doing quite the opposite. The contradictions begin to split a person in two. Body and mind fall apart from each other, and it is in this fissure that an eating disorder may flourish, in the silence that surrounds this confusion that an eating disorder may fester and thrive.

“Curing” a culture is a difficult, if not impossible-to-fulfill order. The conditions, which have created and continue to promote widespread food and body image problems, particularly among girls and women, are multi-faceted and multiplied “deployed,” as Foucault would put it. That is, they are spread out and sustained in myriad ways, mostly with the cooperation of all of us. There is no king to depose, no government to overthrow, no conspiracy to unmask. Moreover, the very same practices that can lead to disorder are also, when not carried to extremes, the wellsprings of health and great deal of pleasure. Maintaining a healthy body weight is important to longevity. Regular exercise not only keeps us fit but makes us feel alive, empowered, strong. Leafing through glossy magazines filled with high fashion imagery is fun and fantasy- inspiring. Even greasy fast food has it (limited) place among the repertoire of pleasures available to us. The problem is that so much that we enjoy and benefit from is part of an industrial/cultural machinery that encourages excess, that doesn’t profit from us knowing when or how to stop. There are thousands of vested interests, in other words, that are enriched by our disorders.

For example: The food marketers continually excite us with images and descriptions of delicious, gratifying meals and encourage us to give in to the impulses those images inspire. But at the same time, burgeoning industries centered on diet, exercise, and body enhancement glamorize self-discipline and toned bodies. The fast food industry tempts us with bigger portions, toys with “happy meals”, and addictive amounts of sugar and fat. Then, television shows like “The Biggest Loser” idealize “last chance” exercising to the point of collapse, and present 5 pound-per-week weight losses as disappointing failure. Open most magazines and you’ll see the contradictions side-by-side. On the one hand, ads for luscious—and usually highly processed-- foods, urging to give in, let go, indulge. On the other hand, the admonitions of the diet, exercise and fitness industries to bust that fat, get ourselves in shape, and show we have the right stuff.

Nowhere among these mixed messages, do we find anything like an ideal of moderation presented. And so, it’s easy to see why so many of us experience our lives as a tug-of-war between radically conflicting messages: to binge, give in to our desires on the one hand, but to get rid of the results—at the gym, over the toilet bowl, through a crash diet—on the other. The individual road we take—avoiding all consumption entirely, for fear of sliding down the slippery slope, or succumbing to the lure of filling our emptiness, restoring our energy, numbing our emotional pain with food, or alternately “bulimically” between the two—will depend on personality, familial, cultural, economic and genetic factors that are varied and complex in their interaction. One thing seems clear: the global spread and increasing diversity of “recruits” into body image and eating problems shatters the notion that either families or biology are to blame.

It’s not surprising that it often takes sensational, revenue-threatening exposes to instigate change. After writer and film-maker Morgan Spurlock documented how he had gained 25 pounds and nearly wrecked his health after a one-month diet of MacDonald’s, the chain stopped offering to “supersize” drinks, and began to develop a line of more “healthy” alternatives. In 2006, Uruguayan model Luisel Ramos, 22, died of heart failure after starving herself in preparation for a show; the same year, 21 year old Brazilian model Ana Carolina Reson, also died from anorexia (Finnegan and Sawer, 2011). In the backlash that followed, Madrid Fashion Week banned underweight models, and various designers, like British Giles Deacon, began to speak out against the “totally unrealistic” images promoted in fashion (Finnegan and Sawer, 2011). In Denmark, after a documentary was aired in which several models told how they were forced to starve themselves before a show, politicians have called for regulations preventing underweight models from their catwalks (Ice News, 2011).

This focus on catwalk models, necessary as it is, is limited to a very specific population and its highly privileged audiences. Making sure that runway models are not anorexic does not begin to address the effects, on ordinary consumers, of the mass images in which their bodies, and the bodies of celebrities, are deployed.

As I argued in Unbearable Weight, eating and body-image problems are complex and multilayered. And the contribution of our culture includes parents, too. A study in the Journal of the American Dietetic Associations found that five-year-old girls whose mothers dieted were twice as likely to be aware of dieting and weight-loss strategies as girls whose mothers didn't diet. 'It's like trying on Mom's high heels,” says Carolyn Costin, spokeswoman for the National Eating Disorders Association, "They're trying on their diets, too.” But this is even to put it too benignly. 'Self-deprecating remarks about bulging thighs or squealing with delight over a few lost pounds can send the message that thinness is to be prized above all else,' says Alison Field (Field et al., 2001), lead author of another study, from Harvard, that found that girls with mothers who had weight concerns were more likely to develop anxieties about their own bodies.

I've been guilty of this. A lifelong dieter, I've tried to explain to my eight- year-old daughter that the word diet doesn't necessarily mean losing weight to look different, but eating foods that are good for you, to make your body more healthy. But the lectures paled beside the pleasure I radiated as I looked at my shrinking body in the mirror, or my depression when I gained it back, or my overheard conversations with my friend Althea, about the difficulties we were facing, as a Jewish and Black woman respectively, who had habitually used food for comfort. When Cassie saw me eat a bowl of ice cream and asked me ifI wrote down my points, I knew she understood exactly what was going on.

So far, Cassie has not yet entered the danger zone. A marvelous athlete, she has a muscular, strong body that can do just about anything she wants it to do; she loves it for how far she can jump with it, throw a ball with it, stop a goal with it. Looking at her and the joy she takes in her physical abilities, the uninhibited pleasure with which she does her own version of hip-hop, theinnocent, exuberant way she flaunts her little booty, it's hard to imagine her ever becoming ashamed of her body.1

Yet, as I was about to serve the cake at her last birthday party, I overheard the children at the table, laughingly discussing the topic of fat. The conversation was apparently inspired by the serving of the cake. “I want to get fat!” one of them said, laughingly. But it was clearly a goad, meant for shock and amusement value, just as my daughter will sometimes merrily tell me 'I want to get smashed by a big tank!' and then wait for my nose to wrinkle in reaction. That's what happened at the party. 'Uggh! Fat! Uggh!' 'You do not want to be fat! 'Nyuh, huh, yes, I do!' 'You do not!' And then there was general laughter and descent into gross-talk, 'Fat! Fat! Big fat butt!' and so on.

No one was pointing fingers at anyone - not yet - and no one was turning down cake - not yet. But the 'fat thing' has become a part of their consciousness, even at eight, and I know it's just a matter oftime. I know the stats - that 57 percent of girls have fasted, used food substitutes or smoked cigarettes to lose weight, that one-third of all girls in grades nine to 12 think they are overweight, and that only 56 percent of seventh graders say they like the way they look. I also know, as someone who is activeat my daughter's school - a public school, with a diverse student population - that it actually begins much, much earlier.

Of course, we can’t ban every ad, fashion spread, video, or magazine cover. But we can challenge the monopoly on beauty that’s been held—and actually, for a very short period of historical time—by the fat-free body. And that challenge has been gathering momentum. This past month, CurvyCon’s New York meeting featured panels in which so-called “plus-size” women told major retailers a thing or two. Barbie, who had become virtually a symbol of early training in body unreality, is now sold in in tall, petite, and curvy versions. Ebony magazine, in March, had African-American recording stars and actress lead a “body brigade” conversation about body image, Black women, and self-acceptance. Meghan Trainor and other curvaceous stars have protested against the digital alteration of their bodies on magazine covers and in videos. (Trainer had her single “Me Too” taken offline because "they photoshopped the crap out of me".) And perhaps most provocatively, the famous Pirelli calendar, until this (2016) year devoted to willowy super-model types, included the powerful thighs of Serena Williams and Amy Schumer’s—gasp!—stomach rolls.

Amy Schumer is hardly what I would call fat. But those soft folds of tummy flesh are a reminder that behind every manufactured image—from the kittenish hourglass of Annette Funicello to the cool, emaciated glamour of Keira Knightly--is a real, human body.

(Taken from “Not Just a White Girl’s Thing,” 2009, “Beyond the Anorexic Paradigm,” 2002), and “The Tyranny of the Fat-Free Body,” CNN Opinion, July 4, 2016)

Works quoted

Abramovitz, B. and Birch, L. (2000) ‘Five-year-old girls’ ideas about dieting arepredicted by their mothers’ dieting’, Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100 (10): 1157-1163.

Black, R. (2009) ‘Plus size model Lizzi Miller in Glamour begs question: Is it time for magazines to show real women?’, NY Daily News, HTTP: <http://www.nydailynews.com/lifestyle/2009/08/27/2000827_are_womens_magazines_ready_to_feature_real_women_.html> (accessed 27 August 2009).

Bordo, S. (1993) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Berkeley: University of California Press.

-- (1997) “Never Just Pictures,” in Twilight Zones: the Hidden Life of Cultural Images From Plato to O.J., Berkeley: University of California Press.

—-(2002)“Beyond the Anorexic Paradigm,” Routledge Handbook of Body Studies

—(2009) “Not Just “A White Girl’s Thing,” Critical Feminist Approaches to Easting Dis/Orders, ed. Helen Manson and Maree Burns, Routledge Press.

—(2016) “The Tyranny of the Fat-Free Body,” CNN Opinion, July 4, 2016.

Choi, C. (2006) ‘Mother’s dieting also affects her daughter’, Lexington Herald Leader, 11 August, B6.

Hornbacher, M. (1998) Wasted : A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia, New York: Harper Perennial.

Natori, J. (1993) ‘Beauty’s New Debate: Anorexic versus Waif”, Harper’s Bazaar, July:P. 78.

Powers, R. (1989) ‘Fat is a black woman’s issue’, Essence, October: 75-78, 134-46.

Riley, S. (2002) ‘The Black Beauty Myth’ in D. Hernandez and B. Rehman (eds), Colonize This!, Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 357-369.

Spurlock, M. (2005) Don’t Eat This Book: Fast Food and the Supersizing of America, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

----- (2004) Supersize Me (film), USA: Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Steven Stark, Glued to the Set (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997), 52–6.

Susan Douglas, Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media (New York: Random House, 1994), 32.

She ‘s now 24, and as athletic and spirited in her body as she was then.

Excellent piece! I think I am going to like it here.

Such a thoughtful and thought provoking piece. Thank you for sharing.