Perspectives on “Oppenheimer”: A Collaborative Work By Susan Bordo and Stephen Faulk

It’s winning all the awards. But perhaps not all the hearts and minds.

Susan:

She puts them both through med school. They both do brilliantly. But somehow (how does this happen?) he receives accolades for his genius as a brain surgeon, while—although she develops innovative techniques in gynecology—she becomes best-known for being beloved by her grateful patients. While he is celebrated with awards, she sits in the front row of the auditorium, clapping and gracious.

The analogy is a stretch, I know. But you do remember, don’t you, that once the studio was so worried that no one would go to see “Oppenheimer” that they desperately mounted a huge campaign joining Christopher Nolan’s film to Greta Gerwig’s. Bring the family. Make it a week-end!!

We got a first clue that “Barbie” wasn’t going to be taken seriously when the male-dominated group who decide on the nominations for the Academy Awards in writing ruled that Gerwig and Baumbach’s screenplay—which was inventive if nothing else—belonged in the “adapted” category because the movie “was based on a previously existing character.”

Then there was the Golden Globes, where “Barbie failed to win best comedy or musical but walked away with the cheesy, newly-invented award for cinematic box office achievement, a consolation prize for being popular and making money.” In this category,“Barbie” competed against “Guardians of the Galaxy,” “John Wick,” “Mission Impossible”, “Spider Man,” “SuperMario Brothers” and the Taylor Swift movie. (Oh yes, and “Oppenheimer,” which was arguably only in this category because of “Barbie’s” box-office coat-tails.) 1

Finally (so far), this past Saturday, there were the SAG awards. They are just for acting, so the most coveted award given was for a film was “Ensemble Cast in a Motion Picture.” Accepting the award for “Oppenheimer” was Emily Blunt in a red dress surrounded by 10 dark-suited men, most of whom I didn’t even recognize as having been in the movie. “Barbie’s” rather more diverse ensemble cast? You’ll find them in the shoebox on the top shelf of your daughter’s closet.

Through it all, Gerwig and Margot Robbie were good-humored about the “snubbing” (as several headlines put it) of their film. Robbie: “We set out to do something that would shift culture, affect culture, just make some sort of impact. And it’s already done that and some, way more than we ever dreamed it would. And that is truly the biggest reward that could come out of all of this.”

All true. But it sure has saddened me to see the most original film of the year consigned to invisibility at the awards shows.

But I’ve already had my say about “Barbie” in other pieces. Today, I want to talk about “Oppenheimer.” And I’m thrilled and grateful to be joined by my friend Stephen Faulk, who contributed the last section of this piece.

Susan:

I’ve seen the movie several times (once in a theatre, then a few times streaming), have read “American Prometheus,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning book that “inspired” the movie, Christopher Nolan’s screenplay, and many documentaries.

After my theatre viewing, my reactions were those of the “ordinary” viewer.

I found it: 1) way too loud; 2) too ambitious in scope: two different films pasted together (making of bomb; political persecution of Oppenheimer) in confusing and too-artsy fashion; 3) Annoying visually. Why does every idea in Oppie’s head need to be represented visually with an explosion? Is it to keep the audience awake during a very long film with a lot of science-talk in it? To prepare us for the big one (surely not necessary)? To entertain the 12-year old boys dragged to see Barbenheimer by their parents? Or are these meant to be representations of what’s going on in Oppenheimer’s brain? (If so, poor guy!) 4) my back hurt from sitting too long in multiplex “luxury” seats.

And don’t laugh (or do)—but “Oppenheimer” reminded me of “Everything, Everywhere All At Once.” Not in its themes, of course, but in its devotion to showing off cinematic ingenuity above all else. I found it an overblown, overbearing show-off of a movie. An assault on the senses and too conscious of its own profundity.

The second time I saw “Oppenheimer” I put my film and literary critic hat on and liked it even less. Christopher Nolan has two irritating habits that shouldn’t co-exist but do in this movie:

He keeps telling the viewer what to think—as in dramatically underscored and over-visualized bits of dialogue. Like:

“What is this place called?”

Pause. Pause. “Los Alamos.” (Wow, I’ve got goosebumps.)

Asked by Niels Bohr if he “feels the music” (of algebra),” Oppenheimer says “I can.” Then we get waves of fire splashing on a shore of glass, a cubist painting (and Oppenheimer transfixed), an orchestra playing Stravinsky, Oppenheimer reading “The Waste Land,” Oppenheimer writing “furiously,” smashing a glass, bouncing a ball against the wall of his room. (I can already see the analysis on a student paper.)

And then, just in case there isn’t enough foreshadowing, in another scene, his lover Jean Tatlock, mid-intercourse, gets up and somehow finds exactly the right book and points to exactly the words she wants (I guess she knows how to read Sanskrit.) She asks Oppenheimer to read out loud:

“Now I am Become Death. Destroyer of Worlds”

Chills! Then Nolan cuts away, to let the prescient profundity sink in.

But while overloading with arty signposts, Nolan also doesn’t tell us enough about what’s actually happening. I challenge you, if you haven’t read “American Prometheus” or seen some good documentaries, to piece the narrative together.

This isn’t the first time my own views are not in step with critical opinion. A welcome exception (from my point of view) was Richard Brody’s review in “The New Yorker”

A hallmark of Nolan’s method—as in such auteur-defining big-budget works as “Inception” and “Interstellar”—is to take the complexities of science, turn them into sensationalist science fiction, and then reinfuse the result with brow-furrowing seriousness. The last step is often achieved by means of chronological or visual intricacies that render objectivity as deep subjective strangeness; strip away such effects, however, and one sees characters conceived in simplistically sentimental terms that are pure melodrama….

These words—“simplistic, sentimental”—are especially apt if you’ve read “American Prometheus.” In that book (also very long, but not, like the movie, requiring one sitting, and can be done in bed) Oppenheimer is not quite such a nice, humble fellow as depicted in the movie—and he’s all the more fascinating for it. The book’s Oppenheimer constantly roused my suspicions about just how honest and self-aware a human being he was. Very, very smart (of course) but also very arrogant, and deliberately projecting humility while actually being very self-righteous. The kind of person who goes on trial and wants to be his own lawyer, thinking he can out-argue and out-charm anyone else (but not even thinking that consciously, because always being able to be the best—the smartest, the most integrity, the deepest thinking—while “just being himself” is so deep in his personality and experience.) Intriguing. I might have dated him. I might have hated him. Maybe both.

Partly, it’s Cillian Murphy’s performance that softens Oppie. We know (from “Peaky Blinders” and the movie “Red Eye”) that Murphy can play sharp-edged, even villainous characters. But there’s nothing cold or insensitive about his Oppie, who is modest and morally thoughtful throughout. Yes, he gets a little carried away, promoting himself to Groves as a candidate to direct the Manhattan project. But that’s just enthusiasm over the science. As a personality, he’s self-effacing and tentative. We never see him basking in the adulation he receives or strutting about his achievements—which apparently the real Oppenheimer was quite capable of. There’s not a scene in the movie in which he appears as Rabi describes him in this quote from “American Prometheus.” Rabi is talking about his demeanor after the successful test of the bomb:

“Afterwards, Rabi caught sight of Robert from a distance. Something about his gait, the easy bearing of a man in command of his destiny, made Rabi's skin tingle: "I'll never forget his walk; I'll never forget the way he stepped out of the car.... his walk was like High Noon ... this kind of strut. He had done it."

It’s not just Murphy’s performance that de-struts Oppenheimer. Nolan subtly edits his reported words, shaving off what’s morally questionable. For example, in the movie, Oppenheimer attempts to give some instruction about the planned bombing of Hiroshima—“If they detonate it too high in the air, the blast won’t be as powerful”—but immediately backs off when cut off by one of the officers packing the bomb into a truck: “With respect, Dr. Oppenheimer. We’ll take it from here.” Here’s how it actually went:

On the evening of July 23, 1945, he met with Gen. Thomas Farrell and his aide, Lt. Col. John F. Moynahan, two senior officers designated to supervise the bombing run over Hiroshima from the island of Tinian. It was a clear, cool, starry night. Pacing nervously in his office, chain-smoking, Oppenheimer wanted to make sure that they understood his precise instructions for delivering the weapon on target. Lieutenant Colonel Moynahan, a former newspaperman, published a vivid account of the evening in a 1946 pamphlet: “ ‘Don’t let them bomb through clouds or through an overcast,’ [Oppenheimer said.] He was emphatic, tense, his nerves talking. ‘Got to see the target. No radar bombing; it must be dropped visually.’ Long strides, feet turned out, another cigarette. ‘Of course, it doesn’t matter if they check the drop with radar, but it must be a visual drop.’ More strides. ‘If they drop it at night there should be a moon; that would be best. Of course, they must not drop it in rain or fog. . . . Don’t let them detonate it too high. The figure fixed on is just right. Don’t let it go up [higher] or the target won’t get as much damage.’ ””

(P. 314, American Prometheus, by Kai Bird, Martin and J. Sherwin)

My point is not historical accuracy. My point is meaning.

“The blast won’t be as powerful” replaces “the target won’t get as much damage.” It’s just a few words, but “the blast” doesn’t begin to convey what “the target” does. Which is, in this particular speech, a callousness, an obliviousness to the actual, living people of Japan (who would soon be so horribly “damaged”.) Nolan doesn’t want to put such callousness into the mouth of his Oppie.

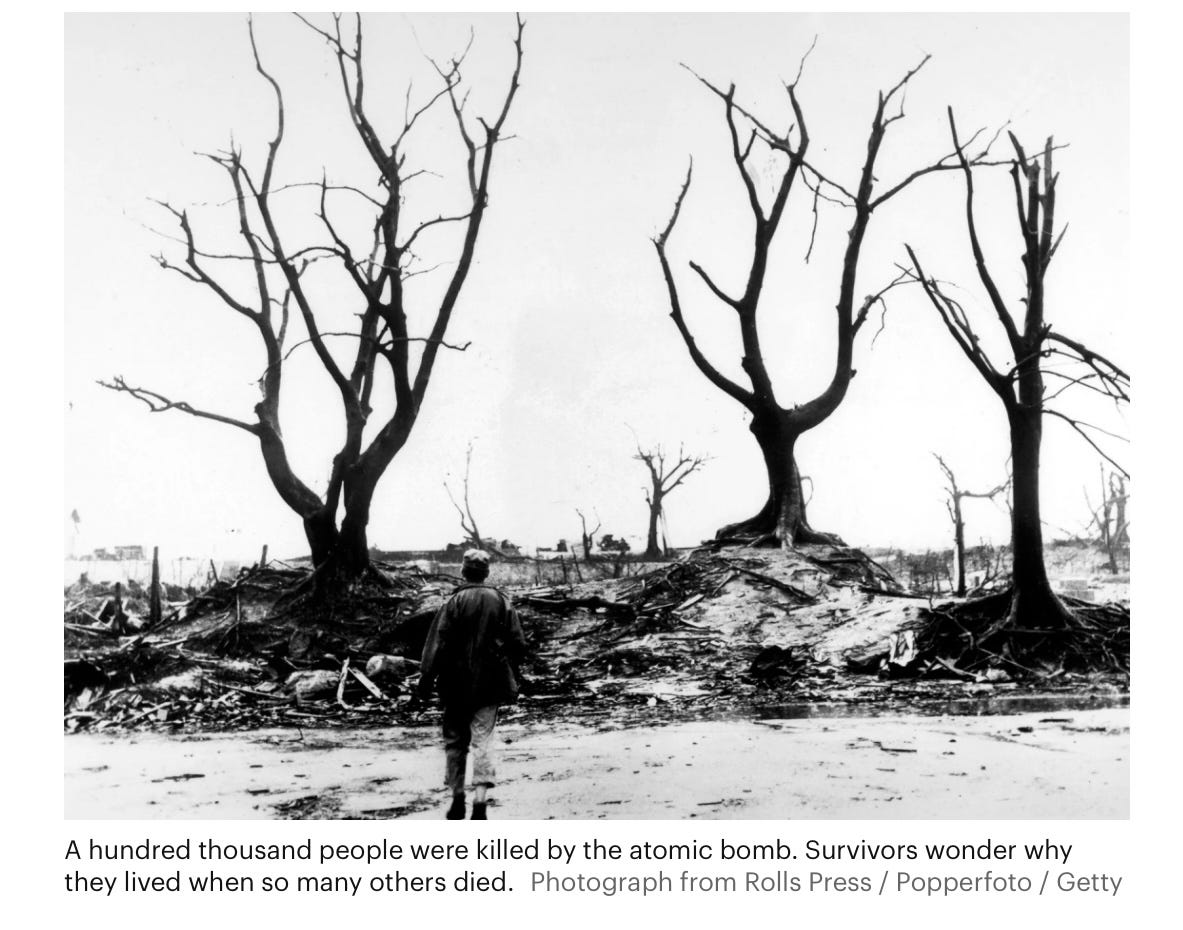

When the Japanese do make an appearance, it’s only as intrusive images—oh, so briefly, a shredded face, a charred body invade his mind as he’s giving a speech celebrating the dropping of the bomb—that signal to the viewer Oppenheimer’s deepening moral qualms. And as such, they are there to say more about Oppenheimer (such a good man, he’s already tormented by what he’s done, while the others, cheering and foot-stomping, are oblivious) than the human reality of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I found this particular scene both unbelievable and repellent. Would Oppenheimer’s rousing words really be punctuated and stalled by horrific inner images? In “American Prometheus,” the event is depicted differently. Oppenheimer “chose to make a dramatic entrance from the rear” and by all accounts, stepped without an apparent inner torment into “the role of conquering general”: “He had grabbed a metaphorical gold ring and was happily waving it aloft.” (p. 316) Bird and Sherman don’t condemn his reaction; the audience expected it, and Oppenheimer was “only human” and “must have felt the thrill of pure success.” That sounds believable.

The thrill, Bird and Sherman write, was “short-lived.” Along with many others of the Los Alamos group, Oppenheimer became increasingly depressed over the horror that he’d help make happen. So the inner torment was real enough. But it didn’t happen in the way depicted. I don’t object to the inventiveness. I don’t expect historical fidelity from “historical” movies. “Oppenheimer” isn’t a documentary; it’s a constructed fiction inspired by actual event. What repels me is the transformation of the grotesque human reality of Hiroshima into a few fleeting images “in the mind” of Oppenheimer. It doesn’t ring true. It’s reeks of a purely cinematic consciousness. It’s too clever by half.

Could the realities of the bomb been represented otherwise? The film is about Oppenheimer, defenders would say. But I’m not so sure. It seems to me to be more about Christopher Nolan, using Oppenheimer as his moral surrogate.

Susan:

Some of you may know that in the screenplay the scenes that appear in color in the movie are written in first person, while the black and white scenes—all of them centered on Lewis Strauss (his view of things, his maneuvering, his confirmation hearing)—are written in third person. So sometimes in the screenplay, Oppenheimer is referred to as “Oppenheimer” and sometimes as “I”:

Nolan has said that the point of writing in first person was to “get inside” Oppenheimer’s “point of view — you’re literally kind of looking through his eyes.”“I wanted to really go through this story with Oppenheimer; I didn’t want to sit by him and judge him. That seemed a pointless exercise. That’s more the stuff of documentary, or political theory, or history of science. This is a story that you experience with him — you don’t judge him. You are faced with these irreconcilable ethical dilemmas with him.”

Set aside for a moment the fact that “looking through Oppenheimer’s eyes” is a pretty ambitious goal, particularly with such a complex individual. It’s also pretty clear that Nolan is “judging” Oppenheimer, just very kindly, leaving out the more unpleasant features of the man.

As to “Oppenheimer’s point of view,” at best the film is inconsistent about that. But the places where it strays are illuminating. What they reveal is the dominance of the male gaze in the artistic choices of the movie.

I’ll discuss the most glaring.

During Robb’s interrogation (done in color, and thus meant to represent Oppenheimer’s perspective) when Oppenheimer is questioned about his relationship with Jean Tatlock, we first see Oppenheimer naked—which is presumably meant to represent in visual terms how exposed and humiliated he feels. Fine. That was jarring, but for that reason, fair. Naive and arrogant about his own untouchability, it was jarring for Oppenheimer to have his sexual life invaded that way.

But then: suddenly it’s not just Oppenheimer who is naked, as we watch wife Kitty silently simmer as a naked Jean Tatlock writhes on Oppenheimer’s nap and then stares straight into Kitty’s eyes. “I may be dead, but I’ve still got him,” she seems to be conveying, upsetting Kitty.

In whose imagination is that supposed to be taking place? Why is Nolan suddenly visualizing Kitty’s feelings? And why a naked Jean? Kitty was appalled at having the affair made public, but by the time of the hearing, she was long past any purely sexual jealousy over by-then-dead Jean. (Tatlock wasn’t the only one, by the way.)

There’s a first person in this scene, all right, but it’s Nolan. It’s his “I”/eye (not an imagined Oppenheimer’s) that has placed naked Jean on Oppenheimer’s lap, taunting Kitty.

Perhaps—just a thought—Nolan didn’t even notice when he switched to Kitty’s point of view. Because in his world, the male hero absorbs everything around him—including, in the case of Jean Tatlock, virtually everything that suggests she was more than Oppenheimer’s depressed, rejected, sex-buddy. Don’t take my work for it. Read “American Prometheus.” There you’ll find that it’s unlikely Jean Tatlock killed herself over Oppenheimer. That she had an MD in psychiatry with a “rewarding medical career.” That the person she tried to reach before her death was not Oppenheimer but another women, whom she likely was having an affair with:

“Some time after Jean’s death, one of her friends, Edith Arnstein Jenkins, went for a walk with Mason Roberson, an editor of People’s World. Roberson had known Jean well and he said that Jean had confided to him that she was a lesbian; she told Roberson that in an effort to overcome her attraction to women she “had slept with every ‘bull’ she could find.” This prompted Jenkins to recall one occasion when she had entered the Shasta Road house on a weekend morning and seen Mary Ellen Washburn and Jean Tatlock “sitting up and smoking over the newspaper in Mary Ellen’s double bed…Mary Ellen Washburn had a particular reason to be devastated when she heard the news of Tatlock’s death; she confided to a friend that Jean had called her the night before she died and had asked her to come over. Jean had said she was “very depressed.” Unable to come that night, Mary Ellen was understandably filled with remorse and guilt afterwards.”

Oppenheimer, although he did remain an occasional lover of Tatlock’s after his marriage to Kitty, was more a “loyal friend” and part of Tatlock’s “support structure” by the time of her death. He did grieve (after all, he’d been in love with her and asked her to marry him several times) and did feel guilt over not being available to her because of Los Alamos. But she almost certainly did not kill herself over him. That too appears to be a fantasy of Nolan’s. Or maybe Oppenheimer’s. Or maybe both. “I”/“him”—they become somewhat entangled in the film, don’t they?

Susan:

The last time I saw “Oppenheimer,” I’d just seen “The Zone of Interest.” And I couldn’t help think about how differently the two films represented the mass murders perpetrated by the Americans, on the one hand, and the Nazis, on the other. I’m not talking about controversy over whether the use of the bomb was “justified” or not, in order to end the war—that’s a topic for a whole other piece, which Stephen briefly discusses in the concluding section of this stack—but rather, the difference in the way the two films asked the viewer to imagine the human horrors taking place out of view of the main action. In “Oppenheimer”: a fleeting couple of disturbing images occurring in the mind of its hero. In “The Zone of Interest”: through virtually the entire film, the screams, the gunshots, the arriving trains, the sound (and smoke) of the crematoriums. A piece of human bone found in the water. And the obliviousness of the Höss family to it all.

“Oppenheimer” and “The Zone of Interest” are, of course, entirely different kinds of movies. But the story of the making of the bomb is in its own way also about obliviousness to human suffering (“My job is just to make the bomb. Not to make decisions about what to do with it”) and I wonder if Nolan couldn’t have/shouldn’t have put that suffering more before us than he did.

Stephen Faulk2, an expert classical guitar maker who teaches English in a Japanese public junior high school, provides some perspective on what we don’t see in “Oppenheimer.”

Stephen:

In the years before I went to art school I learned a lot of art history on my own, from my dad, who was a painter, and from our trips to the Monterey Library.

During one trip, I picked a book about artists from Japan who had survived the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It’s a book which showed a portrait photo of each artist with one of their works, most of which were about the attack or the experiences they had afterwards. I’ve lost track of the name of the book, it’s been nearly 40 years since I’ve seen it, but one photo portrait of an artist from Nagasaki is branded onto the screen of my memory.

His face was dark skinned, he squatted on a tatami. Something appeared to be disjointed about his body, twisted, but under his loose clothes you couldn’t see the adhesions and burns that caused his crouching contortions. His face was one quarter melted as if a bad stroke had burned the his mouth and jaw to droop and branch into a root system of crevices on one side. An eyelid was folded down on itself leaving his eyes placed in radical asymmetrical positions, even though the eye orbit sockets of his skull had not moved. His skull was structurally intact, but the layers of muscle and epidermis over the bone were burned into a non aligned juxtaposition over the cranial structure. Did his nerves break and snap as his skin and muscles slid over the bone ?

My dad looked over my shoulder as I turned the pages in this book and when the page with the guy I described came up he said: “Imagine being that guy and still wanting to and being able to make a painting.”

In 2013 I moved to Japan with my wife who I had had met in the U.S. when she was there working for a Japanese company. She grew up in the big city of Osaka, but was born in a very small town several hundred miles south in Kyushu. We moved to her birthplace, which was full of her older relatives she’d rarely seen, the oldest of whom were in their mid 90’s.

At the time (sadly not now), enough of the old family members were still living to have a yearly family dinner. About 20 people showed up and a few dropped in and left after a half hour. I remember getting mightily drunk on these occasions as my wife’s uncles and great uncles had such a good time seeing how much the new gaijin relative could drink. Pouring non- stop drinks under the guise of being polite old fellows.

I think it was the second year reunion that we attended that I was seated next to an older lady who had visited from out of town. It was purposefully done so we could talk. My wife translated as my Japanese wasn’t that good then, and anyway she wanted to observe the most polite language toward this lady as possible.

She told me her story of being in Hiroshima during the attack by the Enola Gay, the B-29 which delivered the weapon. Although she was ok due to being outside the city that day, she told of the destruction. She was a nurse in her early twenties when it happened, and working in a hospital far enough out from Hiroshima and in a valley or behind some mountains that she was unharmed. But in order to reach a passenger train to get transported to a safe camp or make her journey to relatives, three or four days after the blast she had to walk through the city. She told me she was with a group of people being guided through the city and that they walked for nine hours in rubble and halfway intact streets to an operating train station where they could be taken away.

She died a couple years later after we sat together. I’ll never forget or cease to be grateful for her story. Her kindness was superhuman. Here I had come from the country that built the massive four engine bombers that dropped the atomic weapons, but she was gentle and kept asking if I wanted different dishes to eat or drink. It was my privilege to meet her.

I hear a film has been made in the U.S. about the architect of the bomb, Oppenheimer. I probably will not see this film.

I probably won’t see “Oppenheimer” because first I want to see a movie about what happened to the artist from Nagasaki that I found in the book a long time ago. What went through his mind?

Oppenheimer was an important American figure, but he helped create a situation that Americans don’t want to deal with, which has resulted in the overdetermined American response to the atomic weapon attack on Japan. We perpetually rationalize why we believe it was necessary to drop the bomb, and this became a narrative of blamelessness on the part of Americans which almost shifts the blame to Japan. The state of American victory euphoria birthed a default narrative in which they were given no other choice than to rush the attack, while insiders on our side knew Japanese war cabinet members were embroiled in a dispute over when to surrender.

We’ve enshrined war memorabilia like the B-29 Super Fortress Enola Gay as a symbol of conquest and victory over Japan, which supports the narrative that our hand was forced. Was captain Tibbetts, the pilot of the mighty bomber, a hero or just a messenger sent to deliver a deathly invoice?

Sometimes I test my thesis by entering a discussion in online chats about war in the Pacific. Stealthily, I wait for the entry point in the discussion where I can laser guide my idea that the US rushed into the decision to deploy the weapon, I pick the precise opening. It takes mere minutes to get a barrage of Americans, and often World War II buffs from the UK, to fire back the typical cliche responses: ‘that’s so uneducated.” “define necessary” or the biggest racist justification: “It saved two million American lives.”

In my unpopular speculation, Truman acted in haste. I’ve never read this response to my question of whether the bomb was necessary or not. Posing the idea that America using the weapon was rushed instead of waiting for Japan surrender is met with either extreme defensive, hostility, or scoffed off as mad revisionism.

I know how the Oppenheimer movie ends. He gets shut out of the program and its follow up iterations of development of new nuclear weaponry. His voice is excluded from the unfolding of the Cold War. My speculation is that Oppenheimer was drummed out because he posed a danger of disrupting the emotionally frozen narrative that was pushed in American schools. It couldn’t have been helped, they taught. They say we had to attack Hiroshima. In the Japanese language there’s even a sentiment similar to the American mythology of rationale to have used the weapon- ‘Shikata ga arimasen” translates as It can’t be helped.

When the tempo of American thought slows and contemplates the attack from a deeper perspective and realizes it could have been helped, maybe then I’ll see the film—for its artistic merit and visual aesthetics, because I know how it ends.

The atomic bombing of the two Japanese cities is the mother of all cinema spoilers. In the meantime, I might entertain seeing Barbie for its visual, merit and artistic invention, and probably the more important object lessons it reveals. That is if movies are supposed to have lessons. If they do, the lesson learned from “Oppenheimer” certainly must be one of repeated banality.

Coming next week: Oscar round-up! Quickie takes on all the nominated films.

Oh yeah, Barbie also got “best song” for “What Was I Made For?” The answer, clearly, is “to look pretty and entertain little girls while the boys make bombs.”

Stephen describes himself as “Just a guy trying to keep his lower lip above the poop, and deep sea fishing whenever possible. I teach English in Japanese public jr. high part time. I build concert quality classical guitars professionally. I keep bees for the hell of it, and like cats and dogs. One can never eat too much sushi, or take too many naps. Occasionally I write things down.”

He hasn’t started a stack yet, but if you subscribe to him (profile link at end of this sentence) maybe he will be encouraged to!!

I’d like to share what Oppenheimer’s brilliance did to one American. My Mom is a genealogy nut and about 25 years ago she connected with a distant cousin to my father. They often met to discuss their converging family trees. During one seemingly ordinary met up, Cousin started to weep and was unable to speak. He opened up and shared with her his greatest shame. It seems his home life was filled with violence so he decided to runaway by enlisting during WWII.

During 1945, he found himself stationed in the Mariana Islands north of Guam. Late one evening he was working with a team loading a B~29 plane for a combat mission the next day. Being a young grunt he just did as he was told. Officers in the hangar seemed a bit jumpy and were frequently going out to take a smoke. They had finished up loading and securing a large bomb on board. Cousin’s last task was help secure the cargo doors on the Enola Gay.

Early the next morning the Enola Gay and it’s crew of 11 or so men glided over the target city dropping their payload. The uranium bomb known as “Little Boy” detonated over Hiroshima turning everything in sight to a waste land.

Cousin learned of the bombing when the the Enola Gay returned and the pilot was given a hero”s welcome. For decades afterwards,Cousin carried deep shame and never ending guilt because he unknowingly helped to kill tens of thousands of innocent Japanese.

Like a stone dropped into a pond, the ripples became all encompassing.

Susan - and Stephen - kudos for this terrific deconstruction (or “de-strutting,” in Susan’s words) of the movie *Oppenheimer*, which riled me enough after I saw it to get me to read the actual biography *American Prometheus*. The thing is, with all the critical hoorah about the movie, I first doubted my own response. But reading the bio confirmed for me that the movie turned a complex man into a far more simplistic hero. He was tortured certainly by the aftermath of what he and the Manhattan Project had wrought, but showing it from his perspective in no way compensates for the actual horrific destruction of those bombs and their impact on the Japanese, something Stephen addresses quite movingly.

One of my main takeaways from *American Prometheus* is that Truman and his military advisers were far too hasty in dropping those bombs - and that it was quite likely a chest-thumping show of force meant as a warning to the Soviet Union post-war. Yes, this breaks the usual “America had to do it” narrative - and what a better movie this would have been if that had been the big reveal. I have more to say, but I think this piece gets a lot of my criticisms across with excellent insights and counterpoints. Thank you both 🙏🏽