“Mrs. Astor has taken my Duke of Buckingham!”

I really needed “The Gilded Age” this week. For just an hour, no nausea-inducing political polls. No underground tunnels. No women fleeing Texas. For just an hour.

And the finale gave me just what I needed: Dresses that either ruined ones posture or preserved it (hard to tell.) Great dangling bling. Men with full beards but no “MAGA” hats. Delicious looking little cakes and no glucose monitors. A world in which Dukes are “poached.” In which virtuous, long-suffering Aunt Ada (Cynthia Nixon) is rewarded with an unexpected inheritance and her haughty sister Agnes (Christine Baranski, perfect as always) brought down a peg. A world in which—the Gods of smart, unabashedly ambitious women be praised!—every seat in Bertha Russell’s Met is filled.

“The Gilded Age” was just about the only weekly series this past season that did what HBO and Showtime used to do all the time: made Sunday night something to look forward to.

Carrie Coon single-handedly rehabilitated an archetype that (some bland version of) feminism had hounded off the tube. Bertha Russell, a crafty, imperious member of “new” New York, isn’t just trying to wend her way into the old social order, with its reigning queen, Mary Astor. She intends to conquer it, and her voice drips with her scheming aspirations. She has perfect, snobby enunciation but also a kind of contained sexiness that shows her deep, animal nature. It’s very distinctive—all the other societal ladies simply sound like society ladies. But Coon is a leopard, always holding her pounce back in the interests of decorum, but never letting you forget it’s there, in waiting.

This is a Julian Fellowes (of Downton Abbey fame) production, so you of course never see her in bed with her husband George (Morgan Spector), a wickedly sexy captain of industry with just enough humanity to not fire on children whose parents are on strike but not so much that he feels no guilt over tricking the workers into a deal that will ultimately do them no good. But the Russell’s transactional chemistry is sizzling. You get me the Duke, I’ll let you come to my chambers. And although based on the greediest instincts, they really do admire and desire each other.

Mika, let me tell you, Bertha is a woman who truly “knows her value.” She’s so furious at George for not telling her that her maid propositioned him that she cuts him off completely. (He refused the maid—who has the nerve to later marry into wealth—but his fidelity is not nearly as significant as the fact that the strumpet was allowed to continue to arrange Bertha’s hair after she tried to sleep with her husband.) No amount of “I’m so sorry darling” bling will do—and then he manages to make the Metropolitan Opera House happen, and the door to her chamber opens wide again.

George made me remember the days when my dates could be Republicans so long as they had the right look in their eyes. (Those days are gone; there are no Republicans like that any more.)

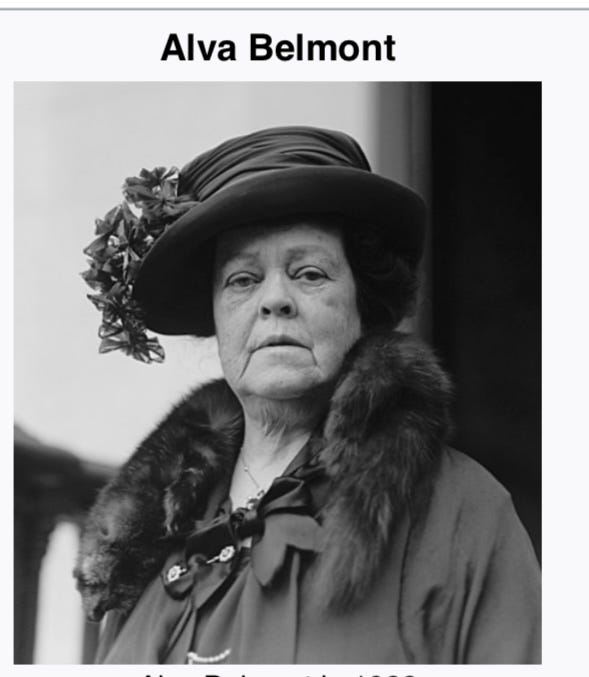

Some of you may not know that Bertha Russell is “based on” Alva Belmont (Vanderbilt,) whose life as a multi-millionaire socialite has many parallels with the character of Bertha in The Gilded Age. (Check out that link to Alva.) So far, that is. I’m not sure that in future seasons (which I hope there are) we can expect Bertha to divorce her hot capitalist husband and become a woman’s rights activist the way Alva did later in life—and I’m not sure I want her to. At least, not too soon, as the conniving, shrewd, unscrupulous pair is too delicious to mess with out of social justice concerns.

In any case, I gave up expecting factual accuracy from historically situated fictions when I toured through Anne Boleyn’s fictional “afterlife” for my book on Anne Boleyn. Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII turns Anne of Cleves into a wisecracking cardsharp who is physically disgusted by Henry rather than (as history tells it) the other way around. A Man for All Seasons neglects to mention that Thomas More, besides being a witty intellectual, also burned quite a few heretics and was apparently not quite the devoted husband he appeared to be. The BBC production of The Six Wives of Henry VIII barely notes that there was a conflict of authority between Henry and the Church, beyond the issue of the divorce. And on and on.

Sometimes if you’re trying to actually teach history it can be a problem, especially nowadays. Historical dramas didn’t used to look “real” enough to pass as quasi-documentaries. But the better film-makers got at reproducing the artifacts of an era (helped a lot by computers), the murkier it’s become. The film of The Other Boleyn Girl, for example, is so attentive to the minutiae of historical detail when it comes to costuming, furniture, hairstyles, etc., that it’s even more mis-informing than the book on which it’s based. When I was teaching courses on Anne Boleyn, students came in believing that wicked Anne “stole” Henry from her virtuous sister Mary (in fact, the Mary/Henry affair was over by the time Anne entered the picture), proposed sex with her brother George in order to conceive a child (no evidence whatsoever) was raped by Henry, and more.

WE HAD A MEME CONTEST WHEN I TAUGHT THE ANNE BOLEYN COURSE

Hillary Mantel, in an interview with me, observed astutely that “all historical fiction is really contemporary fiction; you write out of your own time.” So The Tudors (not wanting to be seen as staid and boring in a “you know, BBC sort of way”) sexed things up a lot, and in the last season of The Crown, Elizabeth doesn’t just participate in a conga-line at the entrance to the Ritz on VE Day (which is true to the facts), she jitterbugs (expertly) with a Black soldier in a cellar nightclub (which she didn’t do; and in reality, the “Pink Sink” in the Ritz’s basement was a gay male hang-out that wouldn’t have welcomed her.) I suppose that the writers didn’t think the conga-line would effectively signal “liberation” for a modern viewer. I don’t mind much that the facts of the “real” Elizabeth were tinkered with. But it makes the contrast with the later, ultra-conscientious, sober (some who knew her have said way too sober1) Elizabeth too extreme, and that creates a problem for the series “as novel.” Maybe a few more scenes of older Elizabeth being jolly—not just droll—or pulling pranks (as she was said to do) would have made the transformation seem less like a body-snatch.

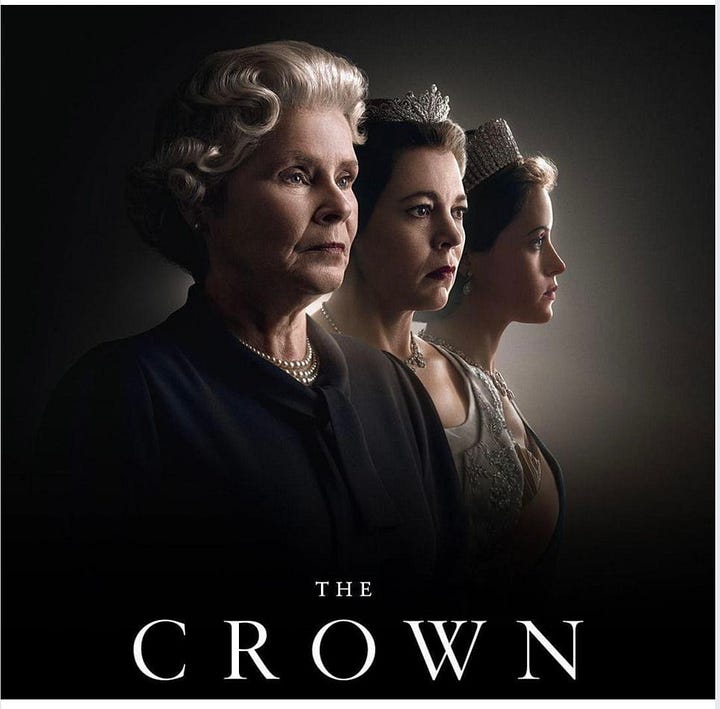

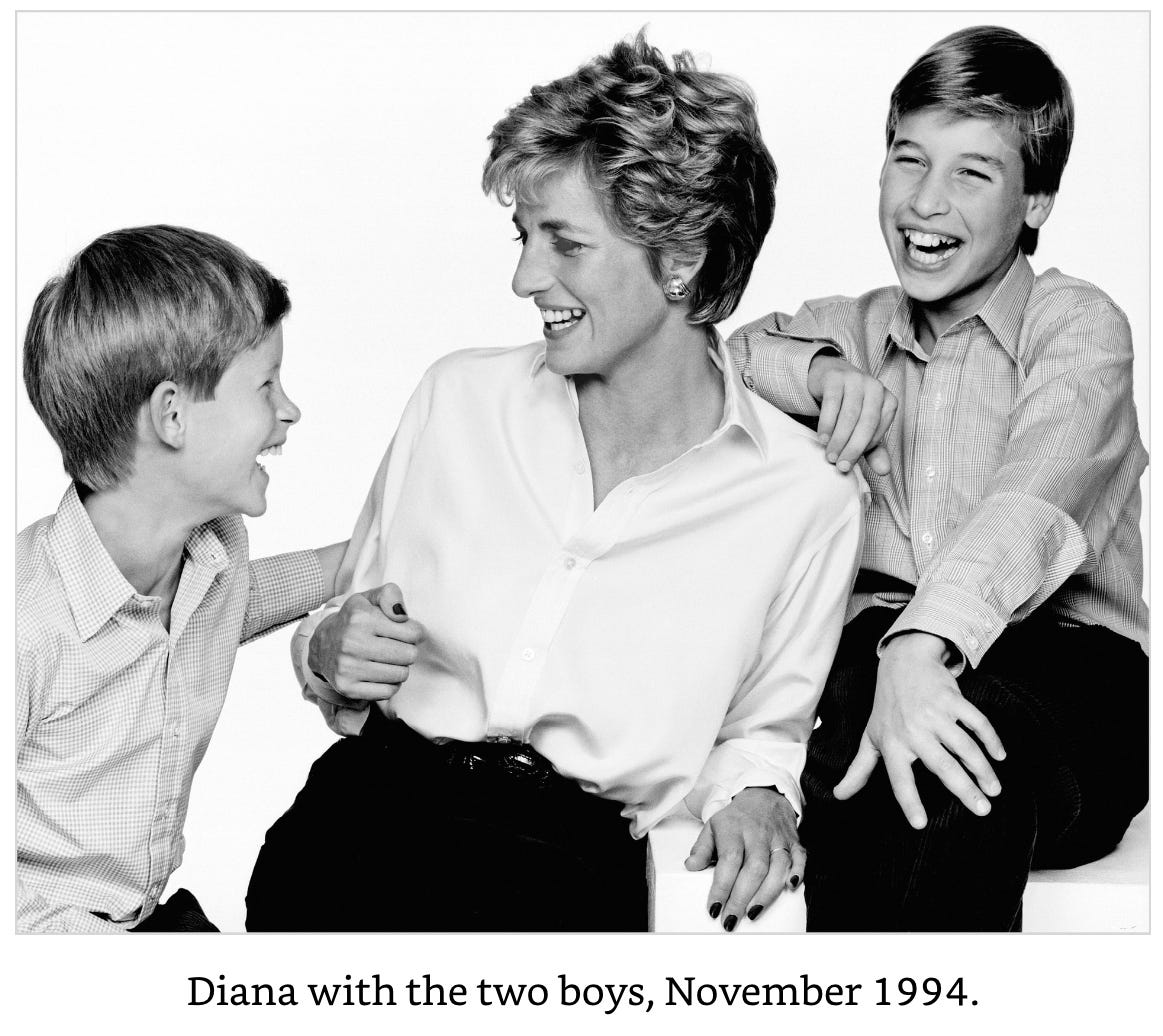

I had problems, too, with the portrayal of William (Ed McVey) and Harry (Luther Ford.) Clearly written in the light of what we know now about William and Harry’s growing alienation from each other, The Crown tends to underplay how much they depended upon each other before their respective marriages—and the weight of their different roles in the “system”—pulled them apart. And I don’t think it’s a trivial thing that Harry not only didn’t look like Harry (I kept seeing a young Eddie Redmayne—who, by the way, was in William’s class at Eton) but that the sharp lines of his face—so unlike the much softer-looking actual Harry—seemed a visual embodiment of a contrast that the writers had decided to construct between the brothers: Harry as an unforgiving, reckless, snippy brat and the so-thoughtful, reserved—and sweetly gorgeous—William.

That would be compatible with The Crown’s generally reverential attitude toward the monarchy, which was accentuated this season by having Elizabeth’s loving preservation of the Keeper of the Swans and other skilled artisans triumph over Tony Blair’s ruthless “modern” attempt to sweep the place clean of antiquated, costly tradition. (He didn’t do too well, either, with his talk at the Women’s Institute; the ladies much preferred Elizabeth’s anecdotes about rationing during World War II.)

But back to William and Harry. You think I’m making too much of the odd casting of Harry? Think about the depiction of the brothers in two incidents, then. In one, Harry harshly chews his father out when he asks his sons what they think of his proposed marriage to Camilla. William, in contrast, is ever-so supportive and encouraging.

Harry, in Spare, remembers it differently:

“So, what do you boys think? [Charles asked] We thought he should be happy. Yes, Camilla had played a pivotal role in the unraveling of our parents’ marriage, and yes, that meant she’d played a role in our mother’s disappearance, but we understood that she’d been trapped like everyone else in the riptide of events. We didn’t blame her, and in fact we’d gladly forgive her if she could make Pa happy. We could see that, like us, he wasn’t. We recognized the vacant looks, the empty sighs, the frustration always visible on his face. We couldn’t be absolutely sure, because Pa didn’t talk about his feelings, but we’d pieced together, through the years, a fairly accurate portrait of him, based on little things he’d let slip.”2

Maybe you’re thinking this is false memory syndrome, or a fantasy cooked up by Harry’s skilled, Pulitzer-prize-winning reporter and ghostwriter, J. R. Moehringer. If so, it certainly isn’t maintained throughout the book, in which neither “Pa,” Camilla, or anyone else in the family is “spared” of a thorough skewering by Harry.

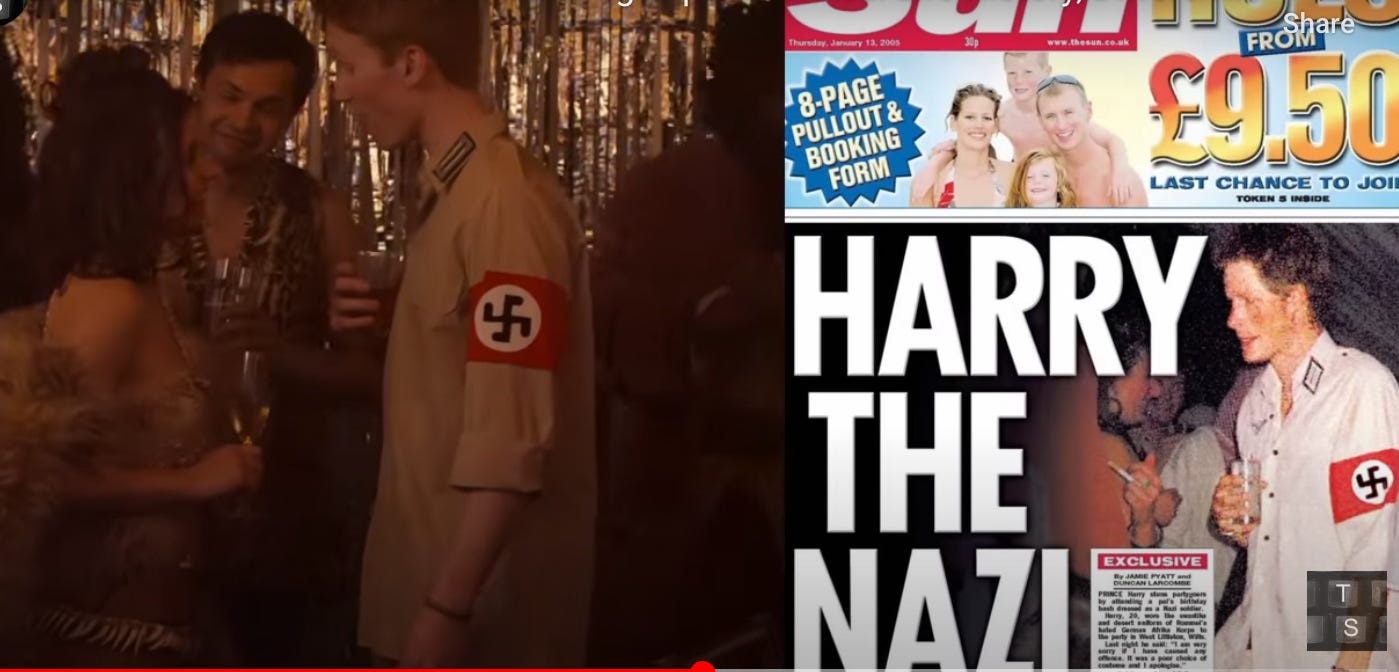

Here’s the other incident in which The Crown seems to want to construct a good/bad duality between the brothers: When Harry chooses an army uniform with a Nazi armband to wear to a “natives and colonials” costume party (a theme that, perhaps, encouraged some tasteless and politically iffy satire?) William’s then-girlfriend Kate Middleton (Meg Bellamy) suggests he covers up the armband—which Harry does with a jacket, but then carelessly removes at the party. Of course, someone at the party has a phone, and Harry gets branded a Nazi by all the tabloids.

The incident did happen, and the reaction of the tabloids was as depicted. But what “The Crown” leaves out is that before the party Harry tried the costume on for William and Kate, and—far from any virtuous suggestions of hiding the armband— they both howled with laughter. And off they all trotted happily to the party. Over-privileged (or perhaps just youthful) brainlessness appears to not be limited to Harry. (In the series, too, “Pa” Charles is so incensed at Harry for wearing the uniform that he throws a glass across a table. In actuality—at least, as Harry recalls in Spare—his father comforted him with “tenderness” and “genuine compassion.” And Harry is sent off to learn a little history from the “Chief Rabbi” of Britain.)

Why does it matter? The Crown is, after all, not a documentary, but a fiction “based on” history. It’s true, too, that the storyline about the brothers had only one season to develop. But imagine how an episode entirely devoted to William and Harry’s relationship—not just brief chunks of playfulness and continual intimations of later alienation—might have changed the feeling of the final season.

When I asked Hillary Mantel about the fact/fiction issue, she replied: “You have to think what you owe to history. But you also have to think what you owe to the novel form. Your readers expect a story. And they don’t want it to be two-dimensional, barely dramatized.” The same goes for the “novel” in movie or series form. Judged in this way—thinking about both its success as a “novel” and what it gets right about history, the relationship between Elizabeth and her sister Margaret inThe Crown was the most effective—and genuinely moving—portrayal for me. They fought. They hurt each other. They were deeply bound to each other. That’s not just the series, it’s what we know from the facts of their everyday habits. They were, even during periods of absence (or even estrangement) indispensable to each other:

“Even after the Queen was increasingly—and, for Margaret, painfully—captured by her duties as monarch, the sisters still spoke on the phone every day. Margaret was the only person on the planet who always knew Elizabeth as a peer, exchanging gossip, complaining about their mother, understanding the world through the same peculiar royal prism. When Margaret traveled abroad, she always unpacked a small, silver-framed photograph of the Queen to hang on her wall or place on her dresser. Jane Stevens, one of Margaret’s long-standing ladies-in-waiting, remembers the inevitable search on their tours for gifts for the Princess to take home to her elder sister.”3

The William/Harry relationship, in contrast, seems like the acting out of headlines: “Harry’s Nazi Scandal,” “Kate Captures William’s Heart,” etc. and it’s hard to believe that they once were each other’s protectors and constant companions and partners in grief.

Elizabeth and Margaret, in contrast, are so believably sisters (and I know something about that, as I’m one of three) that Margaret’s decline and death (the best episode of the season by far) was as heartbreaking for me as Beth’s death in Little Women was when I was younger. And apparently for other viewers too (double-click below for final scene in the episode):

Absolute accuracy can’t be the requirement of historical drama. There is a scene in the 1969 film version of Anne of the Thousand Days that has audiences cheering to this day. Henry VIII (Richard Burton) visits Anne Boleyn (Geneviève Bujold) as she awaits execution in the Tower of London and reflects on the “thousand days” of her marriage to the king. He has come to offer a bargain. If Anne will declare their marriage unlawful and their daughter Elizabeth illegitimate, freeing him to marry Jane Seymour, he will spare Anne’s life. But Anne is having none of it. Her hair disheveled, eyes burning a path straight to his masculine pride, she rejects the offer and spits out a lie: “It is true. I was unfaithful to you with all of them. With half your court. With soldiers of your guard, with grooms, with stable hands. Look for the rest of your life at every man that ever knew me and wonder if I didn’t find him a better man than you!” Rattled and enraged, Henry shouts, “You whore!” Anne has an even sharper arrow in her quiver:

“But Elizabeth is yours. Watch her as she grows; she’s yours. She’s a Tudor! Get yourself a son off of that sweet, pale girl if you can—and hope that he will live! But Elizabeth shall reign after you! Yes, Elizabeth—child of Anne the Whore and Henry the Blood-Stained Lecher—shall be Queen! And remember this: Elizabeth shall be a greater queen than any king of yours! She shall rule a greater England than you could ever have built! Yes—MY Elizabeth SHALL BE QUEEN! And my blood will have been well spent!”

The scene is without historical foundation. Henry never visited Anne in the tower, and Anne never delivered her speech; indeed, at that point, Anne would have known that the chances of Elizabeth becoming queen were slim. Two days before her execution, her marriage to Henry was declared void, and Elizabeth would soon be bastardized. In the movie (and before that, the 1948 Maxwell Anderson play on which it was based), she is given a choice that the real Anne never had.

Does the fact that the tower scene was invention matter to viewers? Not at all. Even today, among audiences who have seen enough alternative versions of Anne’s final days to wonder about the authenticity of any of them, the general consensus about the tower scene seems to be that if it didn’t happen that way, it should have. It did “justice” to Anne in a way that was more emotionally satisfying than the actual facts.

In the case of The Crown, I can’t help feeling that “justice”—fictional or factual—was far from done to Harry. I like what I know of Harry, kvetchy though he often is in his memoir, and I sympathize with his struggle, as I did with his mother’s, to lead a life that isn’t constrained by monarchical traditions. I like Meghan Markle, too, and was horrified (and even a little surprised, as the British usually hide their racism under their classism) by the disgusting onslaught when Harry announced he was engaged to her. Even though Meghan doesn’t appear in the series, which ends before she enters the picture, I bristled at the way the script lavished admiration on the quiet restraint of Kate Middleton (suggesting, for example, that she was the innocent “victim” of her mother’s romantic engineering, when it was actually more like a collusion.) An implicit contrast was hovering, and it irritated me. I don’t know any of the real people, of course. But every time the camera bathed William in princely glow, all downcast eyes in the Diana style, while Harry sat there, sharp-edged and mean-spirited, I wanted to leap up to defend the outcasts.

Maybe I just prefer the upstarts and renegades. Those who defy the rules of the club. Those who lack the appropriate reverence for how it’s done. I’m an American, after all—and from Newark, New Jersey.

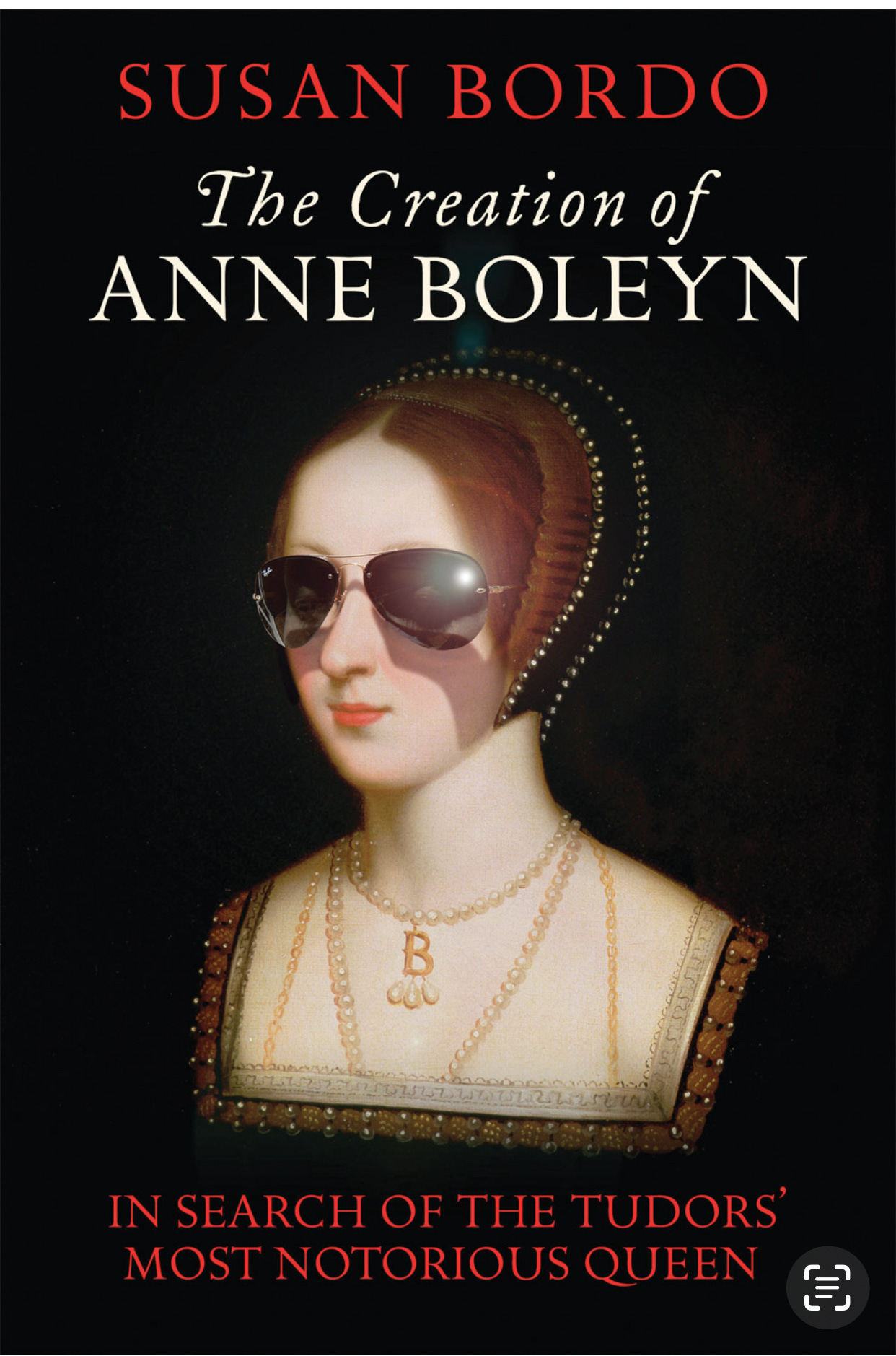

Some British historians were aghast at the cheeky cover for the UK edition of my book. A couple refused to blurb it, despite its great reviews in the US press, because it defaced a historical portrait. (One even wondered whether it was treason.) I loved its witty suggestion, both of the mystery of the “real” Anne, who over the centuries historians, relying on documents from her enemies (and their own sexism) had mangled into a nasty archetype, and the celebrity-status that she achieved, despite her husband’s attempt to erase her from history.

The paperback cover was changed to something less transgressive, and the hardback is now rare and worth a bunch of money.

Bertha Russell would be proud!

P.S. This little bookie would make a great stocking stuffer. And if order one and send me your address (Bordo@uky.edu), I’ll send you a signed bookplate to put in it.

The Queen’s press secretary Arbiter “was withering about Colman and Staunton’s portrayals of Queen Elizabeth over the past four seasons of The Crown—the period in which he worked closely with Her Majesty,” Deadline writes. Arbiter said he didn’t recognize the “drawn” woman played by Colman and added that Staunton’s portrayal was “gloomy in a way that did the Queen a disservice,” the outlet reports.

From “Spare” by Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex.

From “The Palace Papers” by Tina Brown.

Delicious piece of writing!

The season finale of The Gilded Age was very satisfying—absolutely loved it. We recently watched the American Experience on the time period and it set the scene well for the series.

I totally agree about Harry—the Brits have really disappointed me regarding their treatment of Harry and Meghan—very sad and disturbing. I guess in light of the way their politics (not unlike our own) has descended into us v. them fear mongering factions, I shouldn’t be surprised. I would suggest that it’s symptomatic of that phenomenon.

The episode about Margaret and Elizabeth was poignant and very sweet.

In the last episode, I loved the bagpiper and Sleep Dearie Sleep—I cried.

I was curious if Al Fayd did say that about the Brits living in caves and wearing skins when the Egyptians were building the pyramids. I tried to find the quote somewhere but couldn’t find it.

I was also intrigued by the apparent engineering of Kate Middleton’s mom of the relationship between Kate and William.

Do you have any information or insight into those subjects?

Thanks for writing this and for you being you. 💗

The Margaret episode left me in tears---I’ve been drawn to her character throughout the entire series for some reason. And the final episode, when each past Elizabeth appears.... oof, I was quite moved.

I have enjoyed The Gilded Age and was so glad Marion let Dashiel (?) go... that whole storyline bugged me, his presumption.

Do you think the colors/patterns of the gowns are historically accurate? I’m just curious. I sometimes find them jarring and was wondering if the costume dept was taking liberties with their designs.