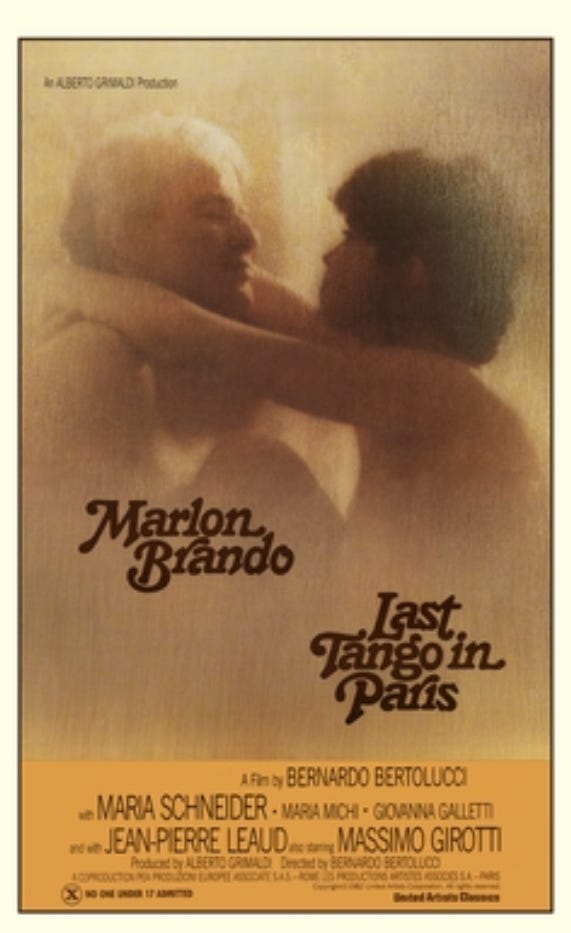

The Male Id as “Sexual Liberation”: Watching “Last Tango in Paris” in 1973 and 2025

I once loved Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris,” A memoir and new movie based on the life of Maria Schneider had me revisit the film, which I now found so upsetting as to be unbearable.

Pauline Kael was my idol when I first saw Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris” in 1973. I loved her irreverence, her disdain for the intellectual snobbishness of other critics, the zingy but literate way she put words together, and perhaps most of all her fierce and often funny anti-Puritanism.

I was into Herbert Marcuse in those days, too—that wacky, intellectually thrilling (to me) blend of Marxism and psychoanalytic theory that linked capitalism and its abuses with the repression of erotic energy and possibility. Marcuse argued, against Freud, that the genital organization of sexuality was not required for "civilization" to function, but rather to serve the interests of advanced capitalism. Freud had accepted that we are all "polymorphously perverse" by nature—we experience pleasure through every organ, every sense, every surface of the body. But unlike Freud, Marcuse believed that we could recover that holistic eroticism without returning to some anarchistic, chaotic state of nature. All that would be required was the transformation of the social and economic machinery of capitalism. No big deal, right?

In 1973, when “Last Tango” came out, I was also a feminist, but definitely of the Germaine Greer variety, critical of all the social and cultural manifestations of patriarchy and misogyny but disdainful of the more sober, ideologically single-minded, and (what we came to call) “politically correct” versions of “the women’s movement.” Greer was the first feminist I read whose work allowed me to believe that it was possible to combine political passion with literary sensibilities, sexual audaciousness, and cheeky humor—and produce work that is deliciously readable as well. I loved her for defying the media-produced stereotypes of the feminist as grim, male-bashing bluestocking, and the lefty in me was delighted to find Marcuse-turned to feminist uses.

For me, just reading Kael and Greer made me feel more polymorphous. Having narrowly escaped (via a nervous breakdown) from my first marriage to a Chicago-school (Milton Friedman, “free market”) economist, I dressed like a D.H. Lawrence heroine, was a heavy smoker (2 packs a day) and so sexually reckless that I can’t remember most of the names of all the men I had sex with.

But this makes it sound like I had a lot of fun, which would be wrong—because I was terrifically insecure and kept falling in love with guys who didn’t treat me very well, and somehow always found a reason to reject the ones who did.

It’s possible that my primary reaction to “Last Tango” was envy of Maria Schneider’s long, slim legs and great clothes. I had the breasts and the hair, but I could never wear those boots—legs too thick. It’s also possible that my enthusiasm for the movie was highly influenced both by Marcuse and by Kael’s ecstatic review, which she had rushed to publish after seeing it at the New York Film Festival on October 14. Comparing the event to the premiere in 1913 of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, she declared “Tango” “the most powerfully erotic movie” and possibly also “the most liberating movie ever made.”

“Brando and Bertolucci have altered the face of an art form,” she wrote. Neither her New Yorker editor William Shawn or her nemesis New York Times film critic Andrew Sarris agreed, shocked by the graphic sexuality—both in the dialogue and the action—and raw, vulgar aggression exhibited by Brando’s character. Neither of them used the term “masculine” to describe that aggression, but Kael—who did not consider herself a feminist—did. For those who haven’t seen the film, I include her summary, and then what amounts—surprisingly, considering Kael’s antagonism toward feminism—to a gendered reading:

When his wife commits suicide, Paul, an American living in Paris, tries to get away from his life. He goes to look at an empty flat and meets Jeanne, who is also looking at it. They have sex in an empty room, without knowing anything about each other-not even first names. He rents the flat, and for three days they meet there. She wants to know who he is, but he insists that sex is all that matters. We see both of them (as they don't see each other) in their normal lives — Paul back at the flophouse-hotel his wife owned, Jeanne with her mother, the widow of a colonel, and with her adoring fiancé (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a TV director, who is relentlessly shooting a sixteen-millimeter film about her, a film that is to end in a week with their wedding. Mostly, we see Paul and Jeanne together in the fat as they act out his fantasy of ignorant armies clashing by night, and itis warfare — sexual aggression and retreat and battles joined.

The necessity for isolation from the world is, of course, his, not hers. But his life floods in.He brings into this isolation chamber his sexual anger, his glorying in his prowess, and his need to debase her and himself. He demands total subservience to his sexual wishes; this enslavement is for him the sexual truth, the real thing, sex without phoniness. And she is so erotically sensitized by the rounds of lovemaking that she believes him. He goads her and tests her until when he asks if she's ready to eat vomit as a proof of love, she is, and gratefully. He plays out the American male tough-guy sex role — insisting on his power in bed, because that is all the “truth" he knows.

What they go through together in their pressure cooker is an intensified, speeded-up history of the sex relationships of the dominating men and the adoring women who have provided the key sex model of the past few decades—the model that is collapsing. They don't know each other; but their sex isn't "primitive" or "pure"….They bring their cultural hangups into sex, so it's the same poisoned sex Strindberg wrote about: a battle of unequally matched partners, asserting whatever dominance they can, seizing any advantage. Inside the flat, his male physical strength and the mythology he has built on it are the primary facts. He pushes his morose, romantic insanity to its limits; he burns through the sickness that his wife's suicide has brought on— the self-doubts, the need to prove himself and torment himself. After three days, his wife is laid out for burial, and he is ready to resume his identity. He gives up the flat: he wants to live normally again, and he wants to love Jeanne as a person. But Paul is forty-five, Jeanne is twenty. She lends herself to an orgiastic madness, shares it, and then tries to shake it off— as many another woman has, after a night or a twenty years' night. When they meet in the outside world, Jeanne sees Paul as a washed-up middle-aged man —a man who runs a flophouse. 1

Such insights into what Kael later describes as “a study of the aggression in masculine sexuality and how the physical strength of men lends credence to the insanity that grows out of it” were pretty much passed over, however, by both the forces of sexual morality and the liberated “left.” The forces of sexual morality were horrified, not by the violence of Paul’s sexuality, but by the nudity, the vulgarity of the language, and the “perverted” nature of the acts that are depicted—particularly the two scenes involving anal penetration: one in which Paul rapes Jeanne using butter as a lubricant, the other in which he has her clip her fingernails in preparation for stimulating him anally. The Parisian censors rated it “forbidden for anyone under eighteen,” and Catholics in both France and Italy mobilized against it—which the Left viewed as “an affront to their freedom of expression.” As described by Vanessa Schneider, Maria’s cousin:

Tango becomes the latest symbol in an ancient fight between the guardians of a certain moral order and the defenders of the artist’s right to create—the wet blankets versus the squeaky wheels. The Italian court condemns Bertolucci, Brando, and [Schneider] to two months in prison with probation. Copies of the film are destroyed. For Bertolucci, the controversy is a triumph. His film has succeeded in garnering the passionate response he desired. It’s discussed in bars and restaurants, debated by artists as well as elected officials. It’s forbidden in the dictatorships of the Soviet Union and Franco’s Spain. Democracies, on the other hand, make a point of defending it. The film is first shown in New York at only one theater, where tickets sell out a week in advance.

(from My Cousin Maria Schneider: A Memoir by Vanessa Schneider)

Repression or Liberation. Those were the two choices.

Pauline Kael chose liberation, and considered Bertolucci a genius. The astute gender analysis I quoted earlier, for her, was proof of that genius and only incidentally an indictment of masculinity. Much more significant for her than any insights into male aggression was Bertolucci’s daring to explore sexuality—both male and female—without romantic filters, to “churn up” (as she put it) and unsettle the expectations and emotions of the audience. She was exhilarated by Brando’s “willingness to run the full course” with the ravaged character of Paul, and clearly was turned on sexually by the movie, too. At times, reading her review, it’s difficult to discern where her sexual excitement ends and artistic appreciation begins. But then, that’s part of what she finds ground-breaking.

I don’t remember whether or not I was sexually aroused by the movie. I might have been. At the time, although I was capable of laying into movies that turned rape into a symphony of male freedom at its most satanic (e.g. Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange”) or portrayed women as obliging sexual handmaids to male rebel-heroes (“Getting Straight,” “Easy Rider”), I also overlooked a lot if a film or work of fiction had that Dionysian/Fuck Capitalism spirit, or broke enough 50’s conventions. In “Last Tango,” Paul rapes Jeanne anally while forcing her to repudiate the repressions of Family and Religion. From the transcript of the final version of the film:

PAUL (CONT'D)

Are you afraid?

JEANNE

No.

PAUL

No?

He YANKS HER by the legs CLOSER TO HIM.

PAUL (CONT'D)

You're always afraid.

56.

He FLIPS HER ON HER stomach, violently. She is not in the

SAME GAME.

JEANNE

No, but... maybe there is some

family secrets inside.

PAUL

Family secrets?

He RIPS HER PANTS DOWN TO HER ANKLES.

PAUL (CONT'D)

I'll tell you about family secrets.

He gets a HAND FULL OF BUTTER.

JEANNE

What are you doing?

PAUL

I'm gonna tell you about the

family.

He YANKS her pants down enough to put his HAND FULL OF BUTTER

in her ASS.

PAUL (CONT'D)

That holy institution meant to

breed virtue in savages.

He SPREADS the butter in her ASS as she STRUGGLES.

PAUL (CONT'D)

I want you to repeat it after me.

He MOUNTS HER, opening his ZIPPER. She STRUGGLES more.

JEANNE

No and no! No!

PAUL

Repeat it. Say, "Holy family."

Come on, say it.

He grabs her arms, stopping her from STRUGGLING as he

SODOMIZES HER.

PAUL (CONT'D)

Go on. Holy family. Church of good

citizens.

She is WEEPING.

57.

JEANNE

Church...

PAUL

Good citizens.

JEANNE

Good citizens...

She CRIES OUT in pain as he enters her.

He smacks her savagely on the back of her head.

PAUL

Say it. Say it! The children are

tortured until they tell their

first lie.

JEANNE

The children... are tortured...

Her MUFFLED CRIES.

PAUL

Where the will is broken by

repression.

JEANNE

Where the will... broken...

repression.

TEARS STREAM DOWN her face.

PAUL

Where freedom...

JEANNE

Free... Freedom!

PAUL

..is assassinated. Freedom is

assassinated by egotism. Family...

JEANNE

Family...

He DRIVES IT HOME TILL HE COMES...

PAUL

You... You... You... You f...

You... fucking... fucking...

family. You fucking... family! Oh,

God... Jesus. Oh, you... Oh...

58.

He COLLAPSES on her, SPENT as she continues to WEEP.It’s possible that in 1973 Paul’s anti-establishment “critique” (I write with eyebrow raised) overshadowed—maybe even disappeared—for me, a violation that now, in 2025, literally makes me want to vomit. The sight of Brando mounting Schneider, holding her down, his body heaving up and down, up and down, up and down, while she barely manages to choke out the words he’s demanded is grotesque, almost unwatchable.

In some ways reading the transcript is even worse, as Bertolucci releases the fury of his own id in his shooting directions, raping, violating, and finally coming along with Paul.

I rarely use the term “misogynist,” which gets thrown around so freely nowadays. But this scene, this writing, deserves the label. Deserves to have it slathered with butter and shoved up Bertolucci’s ass.

I cringe over my younger self when I recall that one of my “favorite” short stories was Norman Mailer’s anti-Semitic, homophobic—and yes, misogynistic— “The Time of Her Time,” the entire plot of which is Mailer stand-in Sergius O'Shaugnessy trying to “give” a young, middle-class Jewish student her first orgasm. I put “give” in scare quotes there because that’s exactly how Mailer sees it: a great gift from man to woman—which his fictional surrogate finally manages by violent anal penetration and calling her a “dirty Jew.” I reread it the other day and thought: How could I? And then I remembered the high-school English teacher who recommended Mailer to me, daring me to not be a prissy girl about it. I think that a lot of what I “liked” in those days was a response to that cultural dare. It was being issued by virtually all the “art” in those days. Be cool, don’t be such a girl.

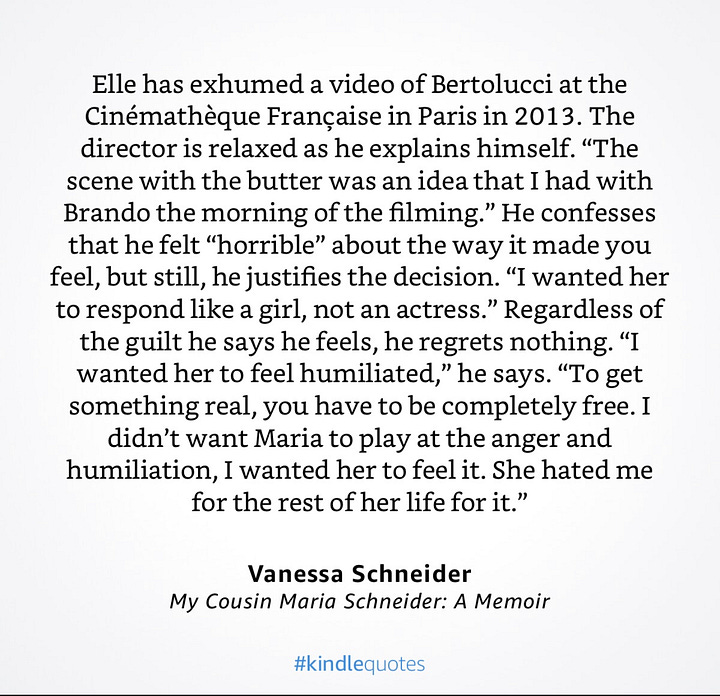

I didn’t know when I saw “Last Tango in Paris” in 1973 that Bertolucci didn’t tell Maria Schneider that they were planning on using butter as a prop in the simulation of Paul’s anal rape of Jeanne.

It wasn’t in the original script—which I couldn’t find anywhere on the internet—but a last-minute “inspiration” that he confided to Brando and deliberately withheld from Schneider so that her shock and humiliation would be real rather than “acted.”

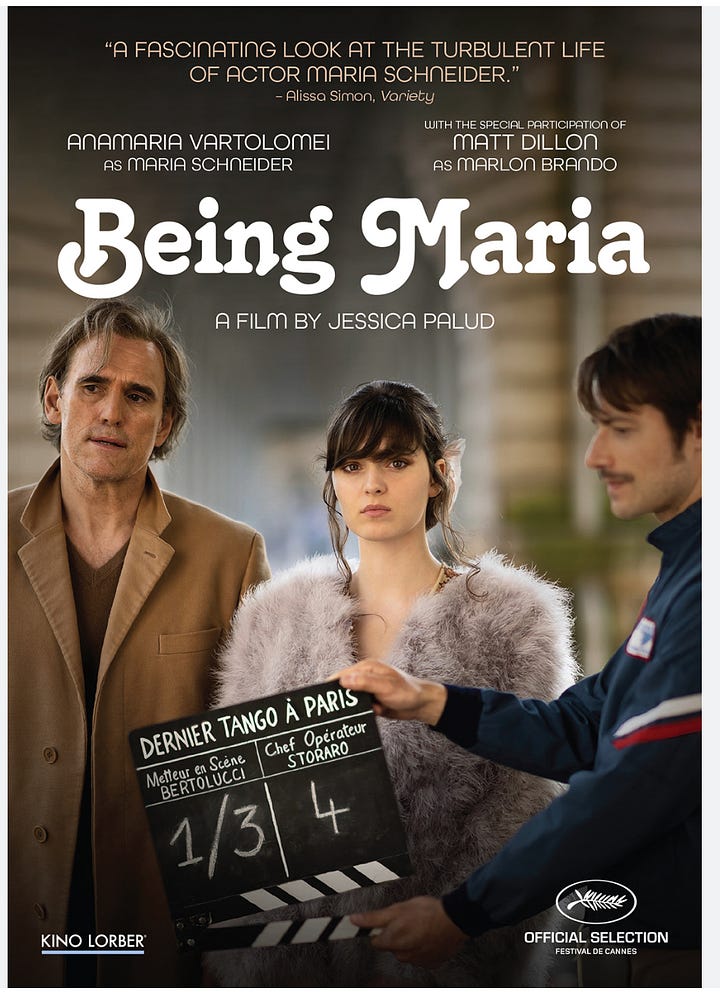

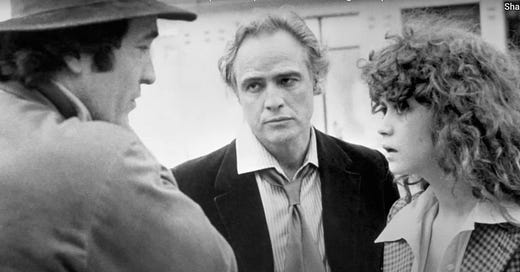

I didn’t know about this until just this past week, when I saw a new (2014) biographical drama on Netflix, “Being Maria.” Directed by Jessica Palud with a screenplay by Palud and Laurette Polmanss and loosely based on Vanessa Schneider’s 2018 memoir, it doesn’t follow either Bertolucci’s film or Schneider’s memoir in exact detail (in the scenes meant to reproduce those of the film, it tones down Paul’s language, eliminates the full frontal nudity, and in general tenderizes the Paul/Jeanne relationships) but like the memoir, it presents “Last Tango” as the turning-point in the downward spiral of Schneider’s career—and life.

As in the memoir, so in “Being Maria” Bertolucci is untroubled by the violation that Maria feels2. He’s uncomprehending as to why she’s so upset, doesn’t understand either why the unconsented-to addition of the aggressively applied butter makes the simulation into an actual rape. Up until then, they’d improvised some scenes, but with a mutuality of understanding of what they were going for. Many of them were playful, children teasing each other. But this scene was a violation not just of Jeanne but Maria. After she runs off the set, Bertolucci is unapologetic: “If I'd warned you, you'd have acted. I didn't want you to act.

On my films, there are no actors, no actresses. Only characters.

The film...and the characters.That's all. I thought you understood that.

Come on. Come, let's do the rest.” (From the script of “Being Maria”)

Of course, she does “do the rest.” She’s a lowly subject being issued the edict of a king, as she now fully recognizes. But the movie—and this scene in particular—continues to stalk her throughout her attempts to get work as an actress, give interviews, even just walk down a city street. Her cousin Vanessa addresses her, in her memoir:

“For your entire life you will have to endure unsavory jokes and cruel pranks. Once, in a restaurant, a waiter asks with an obnoxious wink if you’d like some butter. On an airplane, a flight attendant puts a pat of butter on your plate when you haven’t asked for any. Without your permission, a dairy manufacturer puts your picture on their labels. In Rome, where you are filming René Clément’s Wanted: Babysitter, you’re insulted on the street. More than once you are physically attacked. Faced with this incredible psychological violence, you hide your pain behind a forced laugh and respond with a quip: “I only cook with olive oil.” The press can’t decide what to make of you—whether to love you or to hate you. Feminists wage war over the film. According to them, it goes too far under the guise of sexual freedom. They believe that total submission to the desire of a man symbolizes the alienation of women. Pointing out your youth—the apple cheeks and the look of confusion in your eyes about what’s being asked of you—they wonder if what was captured on film was not art but abuse. They underline the nearly thirty-year age difference between you and Brando and note that in almost every scene you’re naked while he remains clothed. And then there’s the infamous sodomy scene. Some sense genuine protest and suffering in your cries.”

There is a scene in “Last Tango” in which Maria blasts her boyfriend Tom for “making her do things I’ve never done” while shooting his film about her. “You’re taking advantage of me,” she screams at him, “You make me do whatever you want! I’m tired of being raped!”

Is it possible that Bertolucci was unaware of the irony here?

I’ve decided that yes, it’s possible. I suspect that the comparison he’s drawing is not between Tom and himself but between Tom and Paul (i.e. The bourgeois guy is a rapist too.) Perhaps an unconscious recognition that he, too, has raped Maria Schneider in exactly the way she accuses Tom of is bubbling up here. But if so, he never acknowledged it in interviews.

After I re-watched “Tango,” watched “Being Maria” and read Vanessa’s book I turned to YouTube to check out what the internet reviewers were saying. I found an interview with Matt Dillon—who does a surprisingly credible Brando; at times looking and sounding just like him—and Anamaria Vartolomei (who plays Maria, and who you may remember from “Happening”.) Not being a native-speaker of English, Anamaria struggles, understandably, describing her experience making the movie. But Dillon, who is a native speaker, also struggles. He can’t seem to bring himself to condemn Bertolucci, suggesting that “he didn’t mean to exploit Maria.” He is clearly reluctant to topple the director from his revered position in the history of cinema.

That’s true, too, of the several male reviewers—most of them having seen “Last Tango” when young film students—whose videos I watched. All of them had seen “Being Maria”; all of them knew about what happened in the making of the film. But none of them felt it compromised their appreciation of Bertolucci’s “masterpiece.” They passed quickly over the revelations about the “butter scene” to segue to the beautiful cinematography, the raw authenticity of Brando’s performance, the ways in which the film “as cinema” did things that were ground-breaking.

Many of the scenes they found most remarkable—the beginning, in which Paul screams “Fuck God!” like a wounded animal (“lost in a private world of pain,” the transcript reads) and the end, in which Jeanne, having shot Paul dead and being questioned by the police, repeats the words that once was the erotic contract between them—now seem ostentatiously attention-grabbing, and in the case of the ending, irritatingly tricky:

“ I don't know who he is. He followed me in the street. He tried to rape me. He's a lunatic. I don't know what he's called. I don't know his name. I don't know who he is. He tried to rape me. I don't know. I don't know him. I don't know who he is. He's a lunatic. I don't know his name.”

Yeah, we get it, we get it. Very clever.

Tell me, though, Bernardo, did you ever—will we ever—“get” that other “it”?

From “Tango,” reprinted in The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael, Penguin books, 2011, pp.332-3.

As for Brando, in the film he makes an inept, clueless attempt at reassurance: It’s just a movie,” he tells Maria. But as I learned from the memoir, Brando later admitted he felt uncomfortable with Bertolucci’s emotional manipulation of both of them.

Dearest Everyone Who Comments:

I always take a day’s break after I finish a stack. But I will return tomorrow to respond to your comments!!

Susan.

I despised that movie right from the get-go. I didn’t see it in a theater, I know that. I’m guessing I rented it at some video store. I don’t know if I even watched the entire movie--I either missed the anal rape or I've blocked it--but I saw enough to judge it not as art but as one more attempt at exploitative shock to sell movies.

The ugliness of the sex between them seemed so theatrical, so pointedly awful, I didn't feel anything but anger. Not sadness, not disgust, not titillation--just anger. I wondered for a long time why either actor would agree to take part in such a terrible movie. Especially Brando, who was so good in his other movies, so true to his own unique talents, and yet was so utterly and obviously uncomfortable in this role. (I'm guessing Bertolucci was the draw. If it had been anyone else, he might not have done it.)

But at the same time, it didn't shock me that it made waves. I rented it, didn't I? I saw "I am Curious Yellow", I saw "Deep Throat", I saw "9 1/2 Weeks", I read "Fear of Flying", I read Nancy Friday, I read Anaïs Nin...so it wasn't as if I was sheltered. But I hated every Hollywood thing about it. (Though Bertolucci would have hated the reference.)

But I have to say, your take, as always, is fascinating. You go deep, you look at all sides, you personalize your findings, and you make it so damned interesting I wouldn't think of quitting until I'd read the entire thing. So thank you once again. And please keep it up. 😉