Thoughts on Gender and Bodies

In 2023, is the formula “men act and women appear” having a comeback?

Culture is a moving target, and those of us that talk about it have to get used to letting go of any illusions of permanence or ownership. Sometimes, we’re surprised to find our most radical ideas have become daily fare for the next generation, then stale bread to the one after.

This can be frustrating to the writer’s ego, but it’s in the nature of the game. I’ve gotten used to it (more or less.)

When I taught classes on the body, film, and fashion, we talked a lot about “the gaze”—a concept that once was limited to scholars in existentialist philosophy or film theory and that has become a commonplace short-hand for discussions about power and powerlessness involved in the act of looking/being looked at.

The concept has undergone a whole series of transformations since French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre first introduced it; he called it “the look” (le regard) and argued that the mere fact that there are other people in the world, surveying us, defining us, and judging us is existentially threatening.

Sartre didn’t make any distinctions about men and women. But Simone deBeauvoir, who coined another once-obscure concept—“the Other”—that in 2023 even Joe Scarborough throws around (and that has become tortured into grammatical deformity: “othered,” “othering,” etc.) argued that the meaning and experience of being looked at differs for men and women. For Sartre, the look of the other, in encroaching on the freedom of the self, is always “hell.” For women, de Beauvoir argued, it’s more complicated. Being looked at, when the look is full of admiration, is affirming; what’s threatening is being ignored. Women of my baby-boomer generation know exactly what she means.

Feminist writers took these insights in a variety of directions. The “objectification” of women in advertising was explored in many articles, and John Berger’s 1972 Ways of Seeing argued that the formula “Men Act and Women Appear” governed much classical art. Men are depicted as engaged in the world, acting on the world, doing things; they don’t even seem to be aware of being looked at. Women, on the other hand, are depicted as existing precisely to be looked at, and more important, are posed so as to seem aware of it and taking pleasure in it, inviting the gaze of the (imagined) viewer.

Since then, it’s become clear the meaning of “the gaze” varies not only by gender, but by culture, race, and sexuality. Authors in race studies and disability studies have produced powerful accounts of what it feels like to move through the social world marked by one’s skin color or one’s wheelchair, and lesbian film studies (and female directors) have offered a whole new vocabulary of variations, visual as well as intellectual, on the “female” gaze.

And then there is the power of consumerism.

The market is amoral. It can create habits that make people ill and can certainly reinforce (what are perceived as) traditional values, but it also needs to remain alert to emerging trends and previously ignored demographics. And those discoveries can promote progressive changes. Whenever my students complained about capitalism, I reminded them that the beautiful Black models that now fill the pages of Vogue are not the products of progressive-minded executives, but of the recognition that bypassing the needs of Black women was to ignore a potentially huge market. We’re seeing this happen now with plus-size models, too. (So-called “Plus-size” is actually more the norm for American women than model-thin. Incredible that it took so long to recognize this!)

When the first mixed race family appeared in a 2013 Cheerios commercial (the little girl spills Cheerios over her snoozing daddy’s chest to “help his heart”) the fact that the daddy of the adorable little girl is revealed to be Black was met with applause by some but outrage by others. Some viewers wrote on Facebook that they found the commercial disgusting and that it made them want to vomit. Today, it’s hard to spot a commercial—from cereal to cars—that doesn’t feature multiracial and, increasingly, gay families. In fact, it’s hard to spot an all-white family anymore in a TV ad. That’s the power of the profit-motive, recognizing that families don’t always look like the Cleavers.

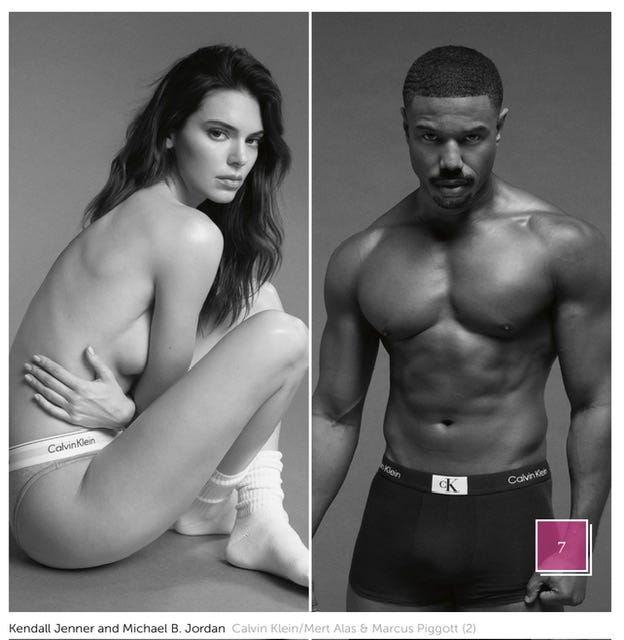

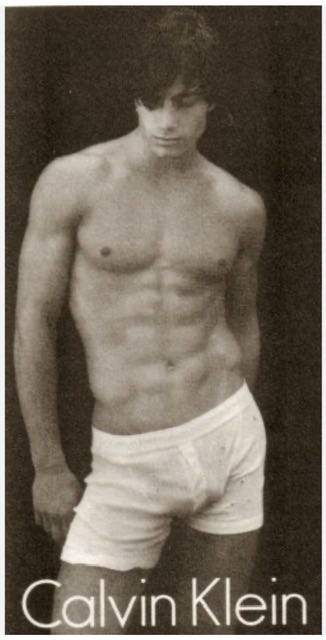

It’s pretty clear that depictions of the male body, even by the time I wrote my 1999 book, had changed, as the eroticization of the male body became big business thanks to the genius of Calvin Klein and other designers. (For a copy of the chapter in which I discuss how “Beauty (Re)Discovered the Male Body,” click here—and please excuse the outmoded cultural references.) ads like the one below, I wrote, had changed the landscape of mainstream images of the male body.

Men in fashion ads, when I was growing up, used to be depicted staring challengingly at the (imagined) viewer, and almost always “in action” rather than offering their bodies as erotic objects of “the gaze.” Then, Calvin Klein, watching the beautifully muscled male bodies dancing in the gay bar he frequented, had an epiphany. It’s not just gay men who wanted to look like that. And women, who often shopped for their male partners, were consumers of these images, too. Hey, maybe we can use the erotics of the male body to market underwear to appeal to gay men, straight men and women too!

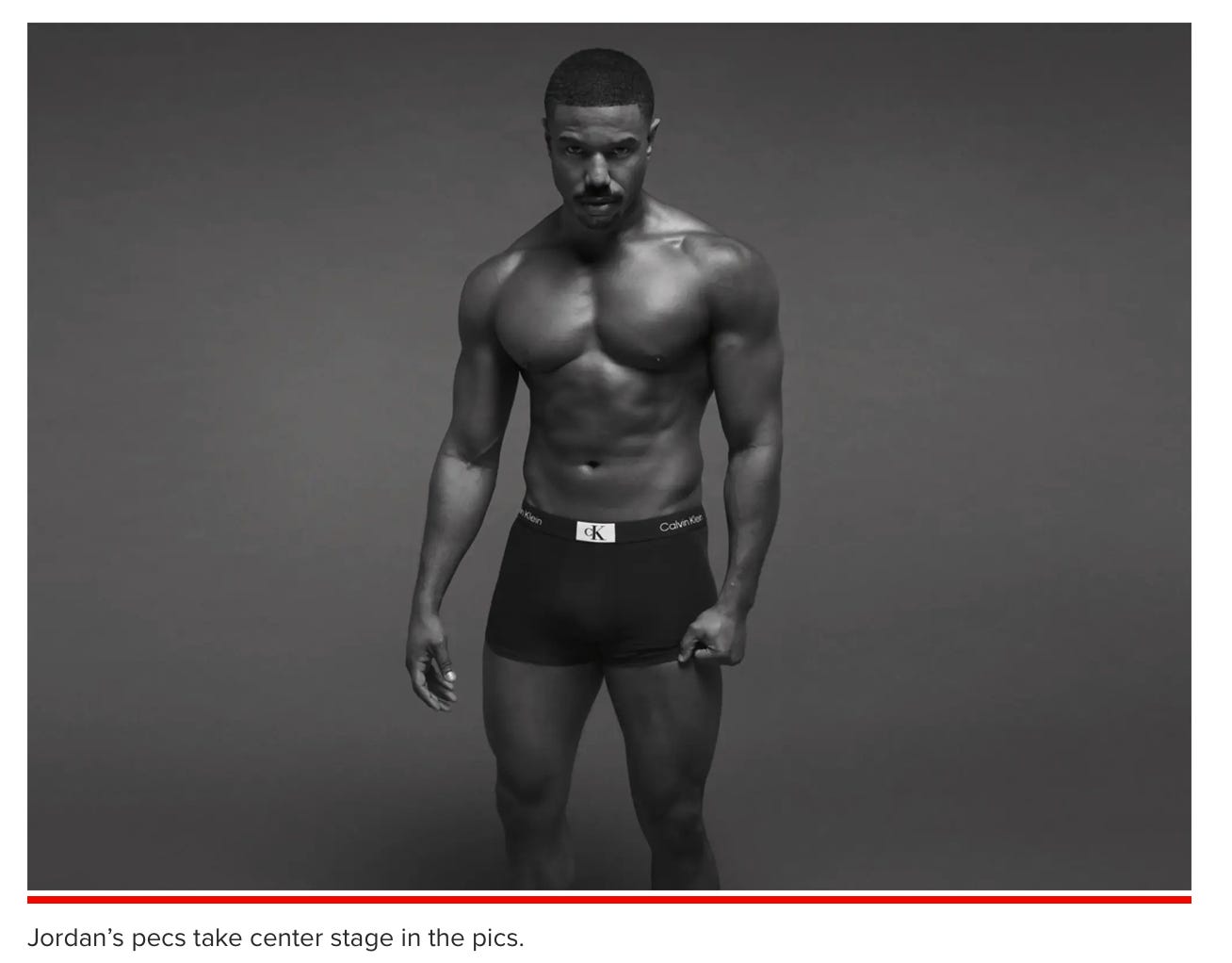

In the same chapter in which I describe losing my composure when I first saw that Calvin Klein ad pictured above I distinguished between two versions of the male body in ads: the “leaners,” which (like the above ad) employ “feminine” body-tropes (eyes averted, s-shaped posture, languid sexuality) to suggest vulnerability and less aggressive sexuality, and “face-off” masculinity, in which men appear just as challenging and dominant as ever, just less clothed. A contemporary illustration: Calvin Klein’s recent ads featuring Michael B. Jordan.

Notice also, in the accompanying article, how “Jordan’s pecs take center stage.” Are we marketing traditional masculinity again, just in more muscular bodies?

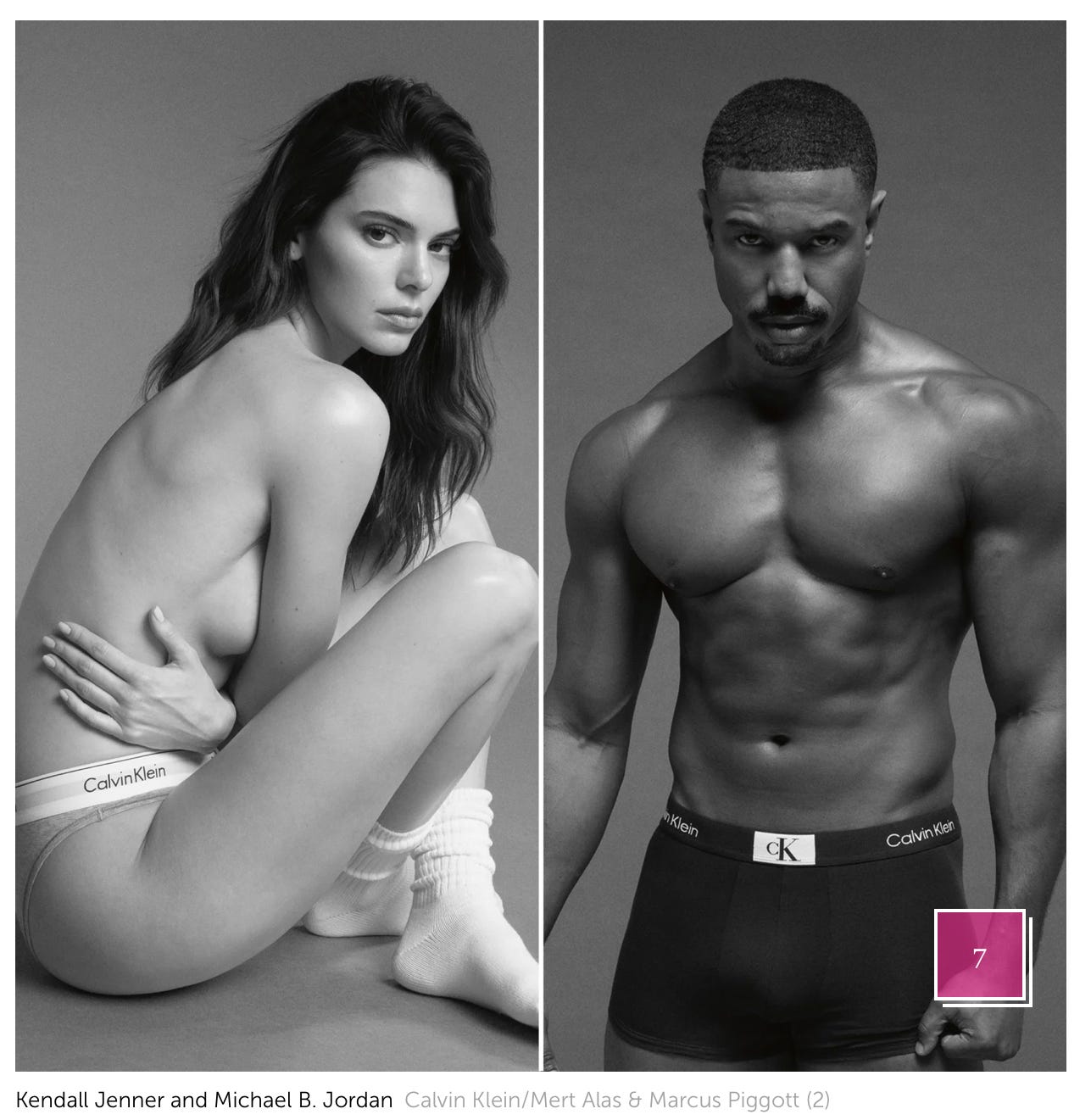

Masculinity and femininity are two side of a culturally-constructed duality, so we can’t really approach that question without looking at the counterpart images of Kendall Jenner in the same Calvin Klein campaign:

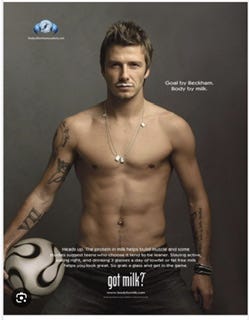

“Men Act and Women Appear” is perfectly illustrated here. Jordan with clenched fist, ready for action (in another era, this ad might have been attacked as embodying a racial stereotype, but we’ve got plenty of muscular, aggressive-looking white versions now too, often employing figures from sports, as in the Beckham “Got Milk” ad pictured at the end of this piece.) 1Jenner huddled in Lolita-like socks, peeking helplessly and slightly suspiciously at the imagined viewer: “Do you like me? Am I pretty?” (And perhaps, as my FB friend Genie Smith suggests, self-protective and fearful over her exposure to an intrusive gaze —paradoxically heightening voyeuristic pleasure over her vulnerability.)

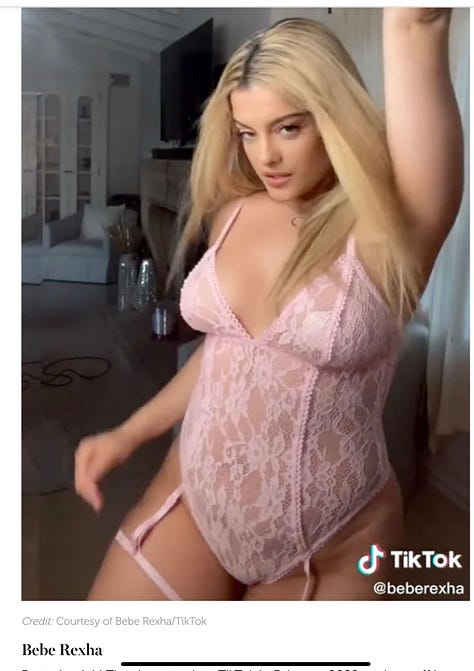

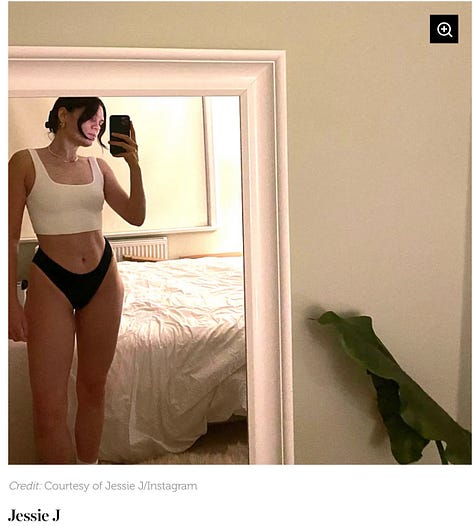

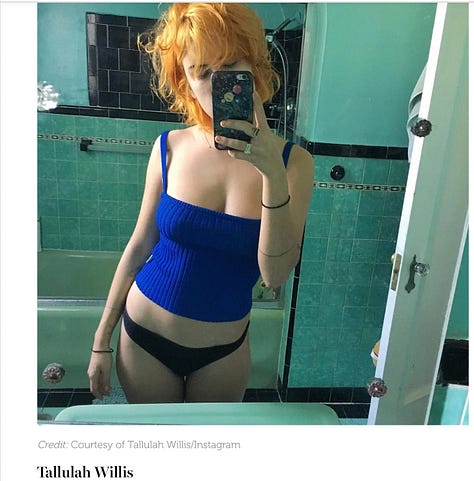

Are we returning to the old formulas? Look at the poses in this collection of women photographed in underwear. Although they are a range of sizes and in varying states of undress, they share that “please look at me” appeal to the assessment of a more dominant “other” (gender irrelevant), the sinuous body-posture, the dependence on the viewer, the retreat from assertion:

When the picture is a selfie, it doesn’t even matter if the “gaze” of the women is totally obscured:

If you have a preteen or teenage girl, you know that these are the prototypes for their own Instagram poses.

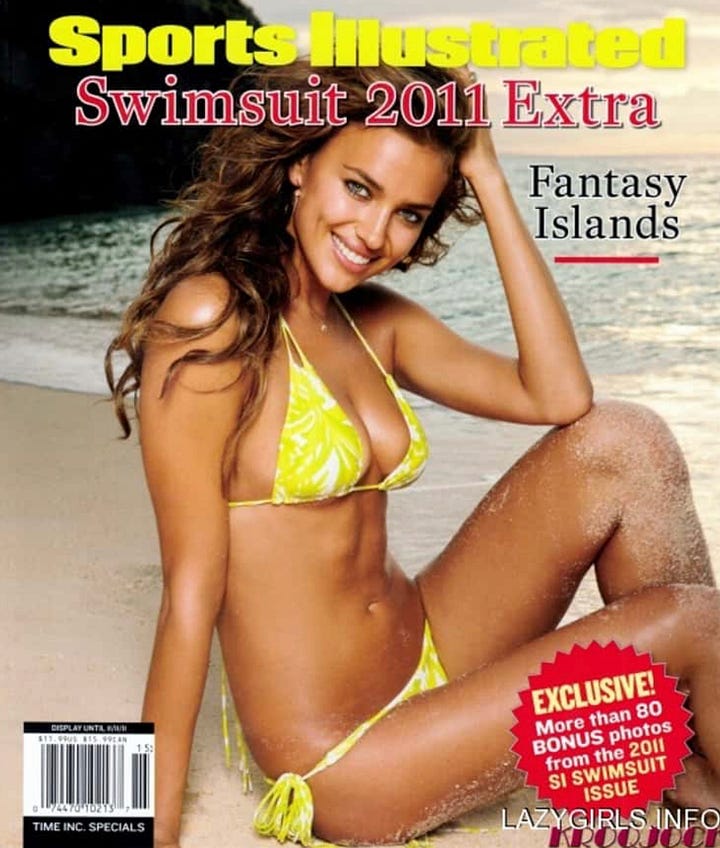

It was striking to me that when Martha Stewart, at the age of 81, appeared on the cover of “Sports Illustrated,” public controversies were entirely about our cultural attitudes toward aging, whether or not she’d had cosmetic surgery, and whether or not anyone had a “right” to judge her. At one extreme were those who saw the cover as a welcome, anti-ageist demonstration that “women can be beautiful at any age”; at the other extreme were those who argued just the opposite: that the cosmetically and digitally enhanced Stewart was proof that we only value youth in a woman. And then there were those that argued a position that has become pretty standard nowadays: It’s Martha’s right to do whatever she wants with her body and any criticism is judgmental “policing.”

Missing from the discussion was the coy, girlish way “Sports Illustrated” had chosen to pose Stewart:

I’m not a body-cop. I really don’t care what Martha Stewart does or doesn’t do, or what her motivations were in agreeing to the shoot.

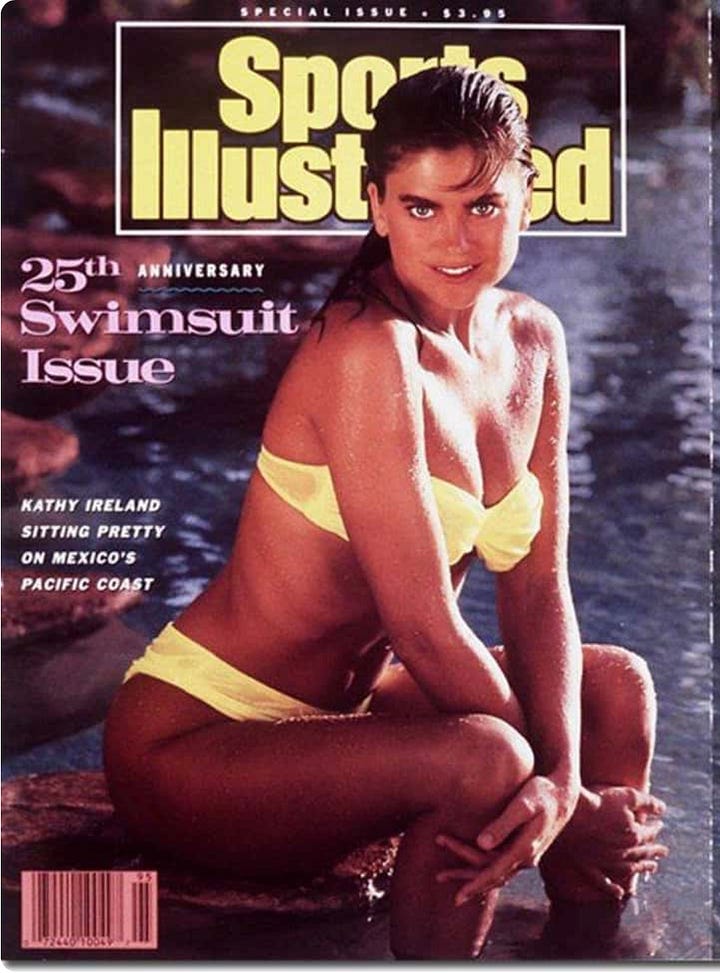

But I do insist that cultural images have meaning. And those images of Martha Stewart are not just “about” skin, hair, breasts, legs, lips, whether or not they are a product of artifice and/or her “individual choice”, how much skin is displayed, etc. etc. In a long tradition of “Sports Illustrated” covers, they are about women’s sexuality as existing for the gaze of the other, and quite pleased with that state of affairs. “Do you think I’m pretty?” “Do you like what you see?” “I’m so glad you do!”

But what did I expect, you say? This is the “Sports Illustrated” swimsuit edition, after all.

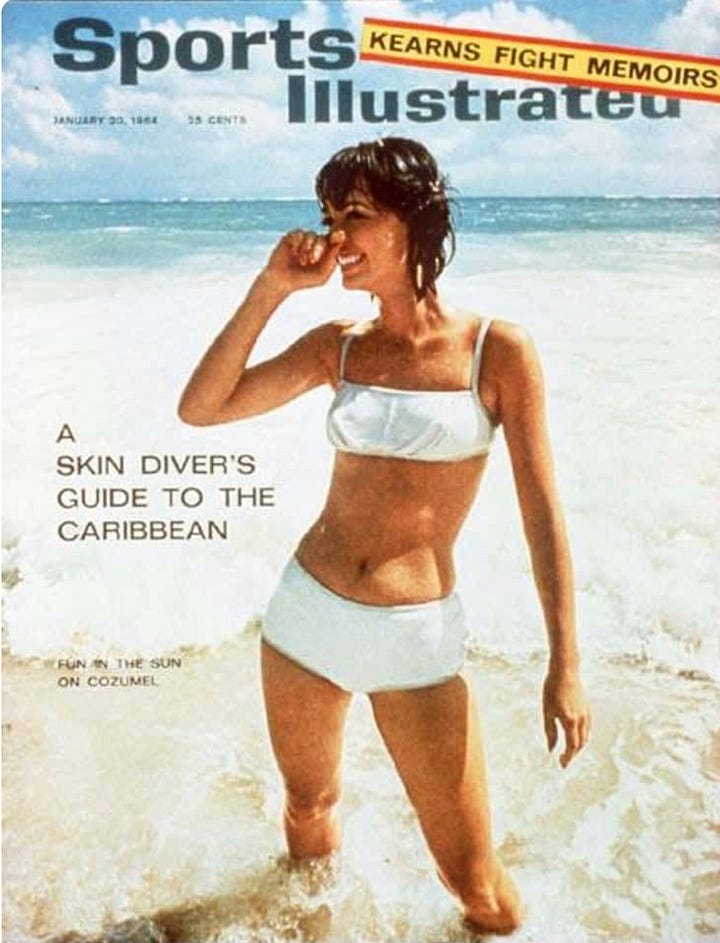

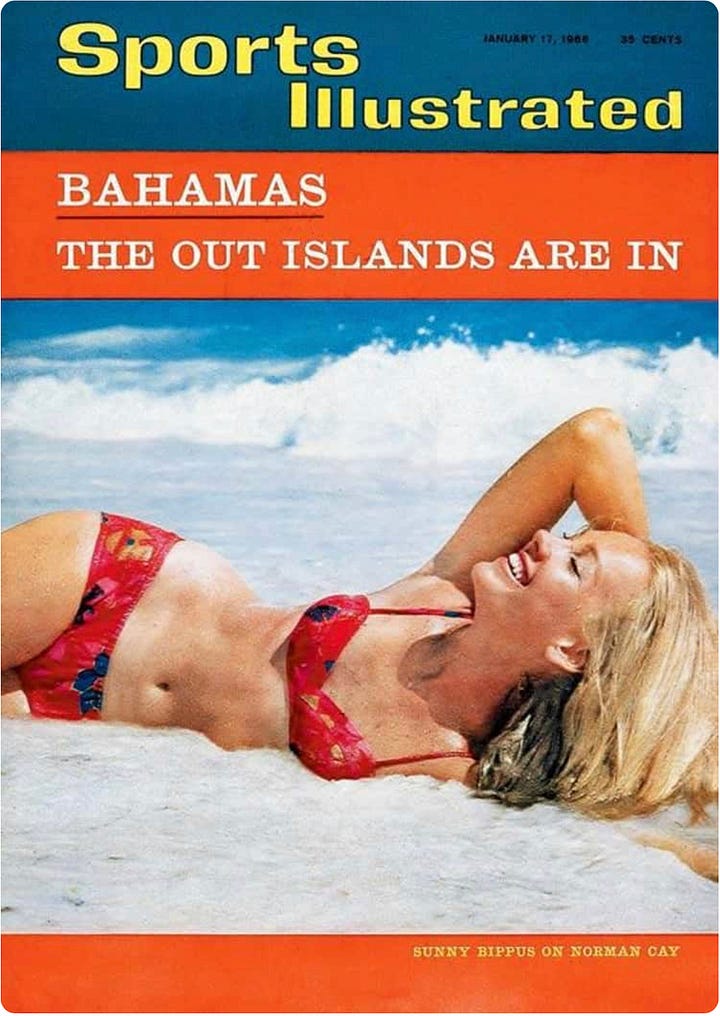

Well, the covers weren’t always like this. Forget the size and shape of the bodies; look at the poses on these 1964 and 1966 covers:

And think about the ways Martha could have been posed, still highlighting her beauty and body, but as actively engaged in her own pleasure, not dependent on the appreciation of the gaze of the other.

Before reading your posts, I had little idea of what gender studies was. And when right wingers threaten to tear apart higher education, they tend to ridicule gender studies. If only they would read this piece, they might get it... well, a girl can dream.

The Calvin Klein ad revolution ... who woulda thunk it had "a history," and it was not some ad director...but Klein himself....realizing what he was doing. Wonder if the gay magazines featured men in these poses, but they didn't realize the meaning of it.

Darn, now I want to look at Hawley's book touting manhood. Hey. Think I will troll his fb account and accuse him of gender studies!

"One of the last taboos to be liberated is to revel in being objectified, and I feel like indulging in taboos sometimes is a way to liberate them.” Dita Von Teese