TV Watch: “The Diplomat” and “Happy Valley”

I’m going to miss Della Street and Siobhan Roy, but there’s still some interesting women with leading roles on prime-time television.

It isn’t just the fact that they both could use a hair-cut

That’s the first thing White House Chief-of-Staff Billie Appiah (Nana Mensah) says about Kate Wyler (Keri Russell) as she sends her off to be the Ambassador to Great Britain.

“She’s a little….[long pause]…She needs a haircut.”

Kate’s departures from the tidy female norm were what I first noticed about her, too. Not just her hair, which looked not just messy but greasy. Or the fact that she’s wearing virtually no make-up. (With a face like Keri Russell’s, who needs it?) But is she actually sniffing the underarms of her suit jacket as she gets dressed? Does she actually ask her husband to smell her? “Is it bad?” She asks. “It’s not great,” he answers.

Later, she demands that her packed suitcase include “no fucking dresses!” And the suits have to be black because (1) she sweats a lot; and (2) she tends to spill her food on herself and after she washes it off, on a light suit it looks like pee.

A messy, sweaty female professional?

Kate’s Wyler’s flaunting of the rules for professional female deportment made me fall in love with her right off the bat. In this, I’m in total disagreement with the Vulture critic who saw Kate’s “refusal” to brush her hair as a sexist trope that views women in power as “so infuriatingly neurotic they can’t control themselves around their attractive peers, refuse to brush their hair, and mock women’s media.” (The latter refers to Kate’s scoffing “What advice do I have for little girls?” when pitched the idea of a glossy magazine profile.) She goes on: Kate’s “boorishness and sloppiness don’t feel like realism — they feel like stuff we’re supposed to find charming because a Woman Politician does it.” And: “Kate is so intent on saving the world that she has no time for manners (biting directly into a gigantic quiche stolen from a country estate’s kitchen), clothes (screaming at an underling, “Pants, no fucking dresses!”), or office niceties.”

Boorish? Sloppy? Screaming? “Neurotic”? “No time for manners?” It seems to me that it’s this critic who has internalized the stereotypes about women in power here. I’m wondering, too, if she’s old enough to remember how Hillary Clinton had to clean up her act (hair too frizzy, glasses too nerdy, clothes not glam enough) as First Lady of Arkansas? It didn’t change all that much when she ran for president. As Pat Schroeder, who had explored a presidential run herself in 1987, remarked: if a man wants to look industrious, all he has to do is “take off his tie, loosen his collar, roll up his shirtsleeves.” If a woman did the equivalent, she’d look like “an unmade bed.” Bernie Sanders was not just permitted, but gloried in the scruffy, charm of the sixties male politico. Hillary was not allowed the same license to be bushy and unmanicured. (Or grumpy.) And then, of course, there was the issue of her “shrill” voice—which I’ll say more about in a bit.

As a young female professor, things weren’t so different for me. When I was about to go on the market for my first job, I was advised how to style my hair so it would look less countercultural. (It was very short and spikey; “less countercultural” code for not heterosexual enough?) At tenure time, the fact that I wore a tattered, Flashdance-style skirt then in fashion was actually raised as an argument against my promotion. I once lost a prestigious job because I “waved my arms around too much” when I gave my job talk. (I’m Jewish, sue me.) Not properly contained.

I’m guessing, too, that she hasn’t been following the viewer reactions to Siobhan Roy (Sarah Snook.) They were outraged that she didn’t do her hair properly for her brother Connor’s wedding. Siobhan broke other rules of feminine comportment, too—she doesn’t walk, she strides, and often several feet ahead of male colleagues. Who does she think she is? An army general or something?

Kate Wyler strides too. So does Catherine Cawood (Sarah Lancashire)—more impressively than Kate, whose slight frame makes it hard for her to appear physically formidable. In the first episode of the current (and final) season of Happy Valley, Catherine, made even bulkier by her protective gear (and some apparent weight gain since the first two seasons; not at all an impediment, it worked well with the trajectory of the character) lopes ahead of two male coppers, boots squishing through the mud, trouser bottoms getting mucky, goes straight to the cut-up body lying in containers in the the marsh, pokes around a bit, and without fuss draws a solid conclusion about who the body-parts belong to. The other two make fun of her apparent confidence, but she’s immune to their macho know-it-all-ness.

Catherine is a cop, not a diplomat, so we wouldn’t expect her to be all tidy and feminine. Oh no? Think about the female cops we’re used to: Jane Tennyson (Helen Mirren) of Prime Suspect, Carrie Mathieson (Claire Danes) of Homeland, Brenda Leigh Johnson (Kyra Sedgwick) of The Closer, Sharon Raydor (Mary McDonnell) of Major Crimes. All impeccable groomed, all beautifully dressed. Brenda Leigh Johnson has a honeyed Southern accent; her successor, Sharon Raydor is soft-spoken and serene to the point of otherworldliness. Jane Tennyson and Carrie Mathieson have emotionally jagged edges, true (as did Cagney—Sharon Gless—of Cagney and Lacey) but never a hair out of place.

I love the two unruly shafts of hair that fall down on either side of Catherine’s bangs. They aren’t without sex appeal or style—but it’s a rebellious, unmanicured style. It says “F-you” to salon-cuts. And if you’ve seen all three seasons of Happy Valley, you’ve seen it grow shaggier, less ladylike as Catherine herself has grown more exhausted with her job, less willing to suppress her impatience and anger.

Why does any of this matter? I’ll quote Andrea Dworkin here, writing in 1974:

Standards of beauty describe in precise terms the relationship that an individual will have to her own body. They prescribe her motility, spontaneity, posture, gait, the uses to which she can put her body. They define precisely the dimensions of her physical freedom….(113-14)

This little girl knows what Dworkin was getting at:

CLICK LINK FOR REEL: MESSY HAIR? DON’T CARE!

In one of my favorite moments in Broadcast News (1987) producer Jane Craig (Holly Hunter), working fast and furious to put together a segment, does everything she can to get her hair off her face and out of the way. It’s an interference with her focus, and although she’s attracted to Tom (William Hurt), she doesn’t give a damn about how it looks. It was the first time I’d seen an onscreen working woman do exactly what I do when I’m intently focused on writing. In general, I consider my hair my best feature. I buy Lolavie shampoo and conditioner, and couldn’t live without my Chi. But when I’m concentrating, please just get it out of my way. Stick it up with an old barrette. Pull it back with Bobby-pins. Get those bangs out of my eyes!

“I’m not bossy. I’m the Boss” (Beyoncé)

Among the many charming aspects of Broadcast News is that—surprise!—Tom isn’t put off by Jane’s intensity but finds it appealing and exciting. I had grown up thinking the worst thing a woman can be is “bossy.” Becoming “political” in the sixties didn’t change that; male politicos still called the shots while we were expected to be what today is called an “ally”: listen and learn, provide support, and keep your mouth shut. How much had it changed by 2016? Judging from how often Hillary Clinton was likened to a domineering wife or a hectoring schoolmarm, not very.

“Bossy” women hadn’t always been portrayed as repellant. In the nineteen-thirties and forties, there were plenty of talking-back, taking-charge women in Hollywood movies (think Katherine Hepburn in “Adam’s Rib” and Rosalind Russell in “His Girl Friday”) who could push back and even push around and still be desired by the likes of Gary Grant and Spencer Tracey. But the post-war idealization of domesticity turned those kinds of women into lovelorn spinsters who paid the price for their ambitions by being alone and lonely. No husband, no children. You don’t want to go down that road, we learned, along with the videos on female reproduction and instructions in becoming a woman. “You’re a young lady now” the booklet that came with my first “sanitary napkins” was called. (If you had no personal experience of such instruction, rent Are You Listening God? It’s Me, Margaret. Rent it whatever your experience; it’s great.) And while male rebels were becoming screen idols, Gidget was fluttering her lashes at a would-be boyfriend.

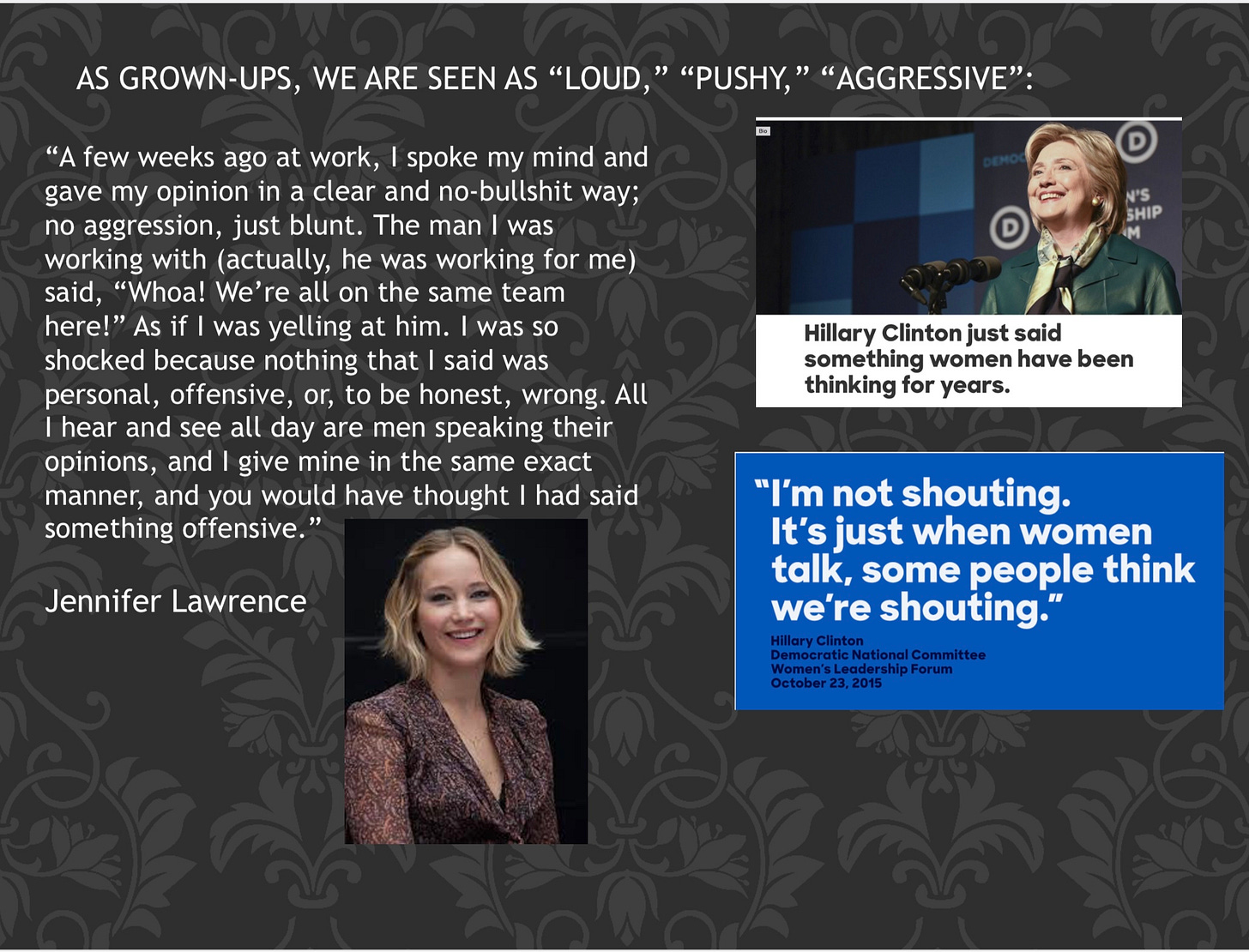

Preparing to write this piece, I was looking over some old PowerPoints, and among them was a keynote I gave in 2016, to a sorority conference, on “Empowering Women’s Voices” (the theme of the conference.) The issue had gotten attention because of how often Hillary’s voice was derided in the mainstream media. Her primary opponent Bernie Sanders was a habitual bellower at his rallies, but pundits didn’t go “ouch” about his speaking voice, the way they did with Clinton. “Why is she so shrill?” “Why doesn’t she modulate?”1 Bob Woodward, on Morning Joe, suggested she “get off this screaming stuff.” Joe Scarborough, who had been interviewing him, agreed: “Has nobody told her the microphone works?”

After Sanders described Hillary as “shouting” about gun control, Hillary put “When Women Talk Some People Think We’re Shouting” up on her Facebook page and campaign website. It was preceded by “Hillary Clinton Just Said Something Women Have Been Thinking for Years.” The slogan caught fire among women, who recognized that Hillary was calling out a truth that went beyond complaints about the decibel level of women’s voices. It went to the experience of being made to feel too demanding, too pushy, too angry, too ambitious, too aggressive, too argumentative, too “bossy”.

Around the same time, actress Jennifer Lawrence wrote a piece in Lena Dunham’s Lenny saying she, too, was fed up and “over trying to find the ‘adorable’ way to state my opinion and still be likeable.”

What isn’t in my slide, which was delivered to a youthful audience whose sensibilities I couldn’t be sure of, was that Jennifer went on to say “Fuck that.” But here, where I’m not worried about offending anyone with my language, I want to note how meaningful that “fuck that” was. Calling out attitudes (or words, as in the “Ban Bossy” movement started in 2014 by Cheryl Sandberg) is one thing; deconstructing them is another. It’s an over-used piece of jargon, appropriated from academia. But “deconstructing” is exactly what Beyoncé does in the video that was making the rounds before criticisms of the “ban bossy” movement (some justified, some not) got it junked.

Beyoncé literally takes the word apart, throwing the “y” in the trash-heap of sexist detritus and re-appropriating the “boss” part for herself.

Call me what you want. If you want to be a jerk, be a jerk. I know what I’m doing, and I know how to do it. And nothing you can say can take that power away.

With Beyoncé’s words in mind, consider the difference between what the series Fleishman is in Trouble does with Rachel Fleishman (Clare Danes) and how Kate and Catherine are represented in The Diplomat and Happy Valley. Kate and Catherine are both unabashedly sure of their own knowledge and abilities. (Here, again, I disagree with another critic of The Diplomat, who sees Kate as a “bedraggled, chaotic disaster whose self-worth is at rock bottom” and leaves the viewer of the show “desperate for someone to brush her hair.”) They are both almost always the smartest people in the room, and while they are struggling, both personally and professionally (if you want a superhero, go see Wonder Woman), their competence is pretty dazzling. (At times, in The Diplomat, I found it a bit too dazzling to be believable.) Kate may not be able to disentangle herself from her interfering husband, but she’s pretty clever at working around him. Catherine knows, just from a few comments he’s made, that Tommy Lee Royce is planning an escape; when it comes to psyching out villainous schemes, she’s the Sherlock Holmes of her (un)happy valley.

It’s striking how many reviews of both shows go out of their way to point out (sometimes admiringly, sometimes—as in the ones I’ve quoted about The Diplomat—derisively) how “flawed” the female protagonists are.2Here’s an admiring one, about Happy Valley’s Catherine:

It matters that we have female characters on television who can be fully, painfully awful, even while they’re also the very reason we’re watching. Catherine is grandiose and bitter. In rage, she intentionally says things to people she loves that she knows will tear them wide open. But doing so doesn’t make her “bad,” whatever that means. She’s a character who doesn’t need to exist on either side of a good-bad binary, because people—messy, kind, traumatized people—generally don’t either. She’s flawed, and she’s riveting.3

I agree that Catherine is riveting. But “grandiose”? “Painfully awful?” I just can’t see how such assessments apply to Catherine. Even when she’s saying devastating things to her sister (for taking her grandson Ryan to see Tommy Lee Royce in jail) it’s hard for me to see her as having the “intent” to “tear” her sister “wide open.” She feels horribly betrayed and she’s in a rage. Her trust has been shattered. She strikes out. It’s painful even to watch as a viewer. But I never had the feeling that she wanted her sister to feel flayed open. I realize this reviewer is making the point that Catherine is human. But the extreme language jars not just with that point but with a character who is gentle even when questioning criminals. You could say it’s one of her super-powers.

To return to Kate Wyler, if you’re actually looking for a “chaotic disaster whose self-worth is at rock bottom” you’d do better with Rachel Fleishman (Clare Danes) than with Kate.

Rachel really is shuffled between “binaries” (thanks again, academia, for another bit of jargon that even Joe Scarborough now uses.) For most of the series, we see Rachel as virtually the Platonic form of the ambitious, materialistic, driven, non-maternal, job-obsessed—and yes, “bossy”—working woman. Brittle. Cold. Lousy values. Etc. But that, as we learn in the penultimate episode, is all wrong—or at least, a hugely distorted, uninformed view. While her husband Toby (Jesse Eisenberg) has kvetched endlessly about her abandonment of her family, Rachel has actually suffered a nervous breakdown that causes her to lose all sense of time. We also learn of a severe postpartum depression, brought on in part by a doctor’s violation of her as she was giving birth. We see the role fears of abandonment have played throughout her life. We see how clueless Toby has been (a welcome turn for viewers like myself who found him insufferable from the beginning.) And so on.

I loved the episode. Rachel’s story—how she became the person that she was—was replete with details that I’m sure were recognizable to many working women from unprivileged backgrounds whose ambitions are caricatured, whose vulnerabilities are ignored, whose struggles are belittled, and whose need for safety propels so many of their choices—even toward marriage with a self-righteous nerd like Toby. Like the women in Rachel’s therapy group, I “get” how one can be raped by a doctor without his penis playing any role at all, and how traumatic and life-changing it can be. And I savored the fact that revelation of her experience validated my annoyance with irritating, holier-than-thou Toby, who we were seemingly supposed to sympathize with for so many episodes.

But then….in the final shot of the last episode it appears that she is going back to him. I’m not sure exactly what we’re supposed to make of this. But it seems to me that in leaving Rachel at Toby’s door, we have been given only two versions of her: one is a nasty archetype that for sure needed to be revised. But the other is a crushed, defeated woman who apparently is going to choose some mistaken fantasy of safety with someone we all know, by then, is unable to appreciate who she is or what she has accomplished.

Is the only way we can make a boss-woman “likable” is to turn her into jelly?

Fuck that.

And do you like my jewelry?

Re-appropriating “likable”

It’s not news that “likability” has been an albatross around the necks (maybe more accurate: a foot on the necks) of women who “lean in” more than is judged appropriate to our gender.

If you want to create a character that viewers will warm to, “likability” apparently has to be negotiated too. Sophie Gilbert, in her review of Happy Valley, says she’s “exhausted” by arguments about likability, but then argues that Catherine is “compelling” despite being grandiose, bitter, bullying, abrasive, etc.—words that are routinely used to describe “unlikable” women. Gilbert doesn’t mention how warm Catherine can be, how tortured she is when a young colleague that she’s chewed out for being soft gets murdered (by Tommy Lee Royce, Catherine’s nemesis) when she tries to play it tougher. Catherine is also very funny, and has her sister Claire in stitches with her deadpan recounting of a farting orgy during Pilates. Personally, I’ve never found Catherine to be grandiose, bullying, etc. and I always like her so, so much (not just found her “interesting to watch,” as Gilbert says at the end of her review.) In fact, I kind of love Catherine.

Then there’s the strategy of having the unlikable woman fall apart or have a secret story that foregrounds her vulnerability—as in Fleishman is in Trouble. Or you can just get rid of the most “unlikable” part—the overly-ambitious part—and have the character defined by what is more appropriate to women: serving. No, not tea and cookies, but her town, or her country. Everyone—even Republicans—adored Hillary Clinton when she was the gracious, only-here-to-serve Senator for New York; her “favorability” plummeted when she decided to run for higher office.

It’s not surprising, then, that The Diplomat makes Kate Wyler totally—and rather unbelievably—without ambition. She doesn’t like being in the spotlight, and hates making speeches (I guess that’s one way of avoiding having your voice criticized.) She wants to do a good job—and is superlative at it—but would rather be doing it helping the women of Iran than being an Ambassador (and certainly becoming Vice-President.) It’s initially irritating because, as Karrin Vasby Anderson astutely puts it in her review (it’s the best one out there, in my opinion) it:

“reinforces one of the most pernicious stereotypes about women politicians on screen and in real life: Women who have political ambition can’t be trusted. In series like “Veep,” “24” and “Borgen: Power and Glory,” ambitious women politicians turn out to be incompetent or corrupt.Conversely, ethical and successful women politicians such as those in “Commander in Chief,” “Madam Secretary” and, now, “The Diplomat” are public servants who have to be cajoled into participating in campaigning and partisan politics.”

On the other hand, although Kate doesn’t like doing public talks, she has no problem speaking her mind, standing her ground, and talking back to others in power. She’s pretty damned “bossy”—and although some men are like Tom in Broadcast News and find it exciting, the male establishment is unnerved. “Is there no way to quiet you?”the British Prime Minister complains—and we’re reminded (as the show does in myriad ways) of the sexist realities behind the show’s myth-making.

The show does something deeper, too, with the “likability” dilemma: It has Kate presenting an argument for re-imagining “likability” as an essential diplomatic skill rather than a self-effacing nod to the requirement that women make themselves smaller (and smilier) than they are. It’s a brief moment, but it’s stuck with me. In it, Hal has just proposed that Kate take advantage of the U.S. Secretary of State’s vulnerability and “break” Ganon, winning the favor of the POTUS and tilling the ground toward Kate becoming Vice-President. But Kate doesn’t want to go that route.

Kate: Do you see... that every time you're backed into a corner, or I am backed into a corner, your best idea is to cut the legs off one of your colleagues? You've left a bloody swath across all of Washington.

Hal: Why does Ganon have to like you?

Kate: Because people do things for people they like. We exist in a marketplace of favors. That has lubricated your journey through the world.

Hal: So Stuart will lubricate. That's not your job anymore. It's his.

Kate: I didn't do any of that because you did it for me. I was doing something else, right? If everybody hates you, it all stops.

The exchange brought me back to the year that I was acting director of Gender and Women’s Studies and going through the steps to have the program made into a full-fledged department. In shepherding the process, I had to respond to a lot of skepticism about the value of a “whole” department devoted to gender (and those were, from the perspective of 2023 and the good old days!) I also had to meet with many old white guys who chaired important committees and held positions that could make or break our efforts. Did I “lubricate” Gender and Women’s Studies journey to department status by being as charming as I could be with those guys? You bet I did. Did I treat every objection, no matter how sexist, with respect, answering seriously and carefully avoiding giving offense or feeding any stereotypes about feminists. I did. Did we become a Department? We did—not only through my efforts, but certainly “lubricated” by them.

“If everybody hates you, it all stops.” That’s true. It’s also true, however, that if you are hated because you refuse to make yourself smaller than you are no amount of skillful diplomacy is going to conquer an irrational recoil that is immune to reason and fed by caricatures. We saw that, surely, when Hillary-hate, stoked by Russia, Trump, Sanders, and the mainstream media help propel a lethally unscrupulous idiot into the presidency. The Diplomat, however, is a television show, and although it’s a fantasy, “the vision of a candid, nonpolitical woman who wins powerful men’s respect by exposing flaws in their logic” (as Kate repeatedly does) “is a good thing. As the 2024 campaign season ramps up, voters need compelling reminders of the effect sexism can have on democracy – because patriarchal political culture is something we all have to negotiate.”

The Husband and The Psychopath

The Husband.

There are two ways to look at Kate Wyler’s relationship with her husband, Hal Wyler (Rufus Sewell). They aren’t mutually exclusive; actually, they need each other for the show—which creator and show runner Debora Cahn describes as primarily about relationships—to work.

Hal’s character bio, supplied by Netflix, describes him as “a brilliant and charismatic diplomat.” He’s “negotiated the end of wars, but made a lot of enemies along the way. He wants to be a supportive husband and let Kate shine, but standing outside the spotlight doesn’t come naturally to him.” That’s a gentle way of putting it. More accurate would be: an ego-driven, totally undependable obstacle, and not at all the helpful ‘wife’ that he pretends to be. He lies to Kate, he has ambitions he hides from her, and his seeming self-effacement is clearly a performance—and an unsustainable one: When they first arrive in England, he tells everyone who addresses him as “Ambassador” that he’s “just Hal” (“Are you going to do that every time?” Kate asks); but when he’s attending the first official function, he insists on “ambassador.” He seizes an opportunity to advance his own ambitions when Kate asks him to pitch-hit for her at a prestigious talk. And it’s pretty clear by the end of the season that despite telling Kate how much “fun” he’s having “being a back-up singer,” he’s got his eye on the position of Secretary of State. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t want Kate to dump him and get it on with Austin Dennison (David Gyasi), the hot Foreign Secretary who can “barely breathe” when he’s in a room with her.

So why is she still with Hal? There are probably a dozen reasons, from the comfort of being with someone you can trust to sniff your skanky underarms and still want to have sex with you to the fact that she is still, on occasion, dazzled by his political savvy. There’s a ton of backstory we don’t have, too, about the fifteen years they’ve been married before the events of the show unfold. (We don’t know, for example, whether not having children was a choice or something else.) We don’t know what Kate’s childhood was like. We don’t know what she was doing when they met. We don’t know what kind of crises they helped each other deal with.

There’s a lot we don’t know. What we do know is that they’ve been together for fifteen years. And for the creator and show runner of the series Debra Cahn, that’s the most salient fact:

“ It’s hard to keep a relationship going over time, be it a marriage or a military alliance. We change, we grow, the world changes, and yet we want these relationships to last. [The Diplomat] is a show about a bunch of good people doing their best to keep their partnerships alive, while trying not to kill each other.”

I bolded that last bit because the fact that we do indeed want to kill Hal (vicariously, for Kate) is such a great antidote to the fantasy of the endlessly supportive husband of infinite patience who sends his working wife off every morning with a hearty breakfast (Norm in Fargo) and has no problem making dinner for the kids when she stays late at work. Who never gets jealous or resentful. (Martin Ginsburg in On the Basis of Sex; Paul Child in Julia) Whose masculinity is so sturdy he never feels threatened. Who sticks by his wife through alcoholism (When a Man Loves a Woman); Alzheimer’s (The Notebook) and amnesia that leaves her forgetting him entirely (Leo in The Vow.) I’m not saying there aren’t partners like this. But mostly, these movies—many of which I love—leave us looking at our own partners and wondering “Why aren’t they more like that?”

In The Diplomatic we get a relationship that is so much more like real life, in which husbands can be total assholes and longtime partners stay together despite each other’s worst qualities, for reasons that are as various, mysterious, and completely understandable as there are partnerships. Hal drives me crazy. He drives Kate crazy too. Yet she stays with him. That makes their relationship a source of dramatic tension as well as a bit of realism in what is otherwise kind of a fairy-tale. She’s got a sexy foreign secretary who wants her despite her greasy hair. She’s got people pursuing her for the job of Vice President. She cleans up really well, thanks to a stylishly thin body. And she’s really, really smart. Think how insufferable she would have been if the husband was a Prince Charming too.

The Psychopath

Every superhero deserves a super-nemesis. Catherine, although described by Gilbert as “an ordinary woman,” is far from that. Every day she has to clean up the messes, both trivial and significant, made by those in her charge, and describes herself, without apology, as uninterested in dealing with things “rationally”; her goal is to deal with them “effectively”—and she usually does just that. She doesn’t care that her boss (as well as her sister) see her as too obsessed with Tommy Lee Royce (James Norton), a drug dealer/rapist/murderer whose rape of Catherine’s daughter Becky left her pregnant and suicidal. In fact, she nurtures her hatred. She cannot—will not—forget that after Ryan (Rhys Connah) is born, Becky does kill herself, and she finds it “unfathomable” that anyone would see Royce as anything but the lowest form of scum. As far as Catherine is concerned, Royce has rescinded all claim to human understanding, and as she raises Ryan, she’s both anxious over the possibility that Ryan may have inherited some of Royce’s tendencies, and determined (without success) to keep him out of Ryan’s life.

The trail of human damage Royce leaves throughout the three seasons is matched only by Catherine’s righteous fury, which has gripped her since season one, and which is a thread that links all the seasons together. As James Norton notes, it’s almost like a marriage—not one born out of love, but of mutual obsession:

“Tommy constantly forces his way into her life and her consciousness. They are in the best way, in that sort of old-fashioned way, epic adversaries pitched against each other [with] a kind of deep, deep hatred in the way that when you think about someone that you hate they inhabit part of your consciousness….There’s a certain kind of shared experience they have in that they both obsess about each other. In that way they are inextricably linked and will always be in some way married together.”

In the current season, Catherine discovers her sister Claire (Siobhan Finneran) and her boyfriend have been secretly taking Ryan to visit Royce in jail, and—in some of the most painful scenes in the series—it shatters her trust in her sister, who has been the most enduring relationship in her life (she occasionally has sex with her ex, but it’s mostly to get some relief from everything she has to deal with.) When Royce engineers an escape with the help of the town’s drug kingpin (not yet known to Catherine is the fact that he’s hoping to convince Ryan to fly away with him to Malaga,) everyone who is in danger from Royce goes into hiding at industrialist Nevison Gallagher’s (George Costigan) relatively luxurious house. And while Catherine may (or may not) have planned to join them, but when she sees Claire and Neil relaxing on Nev’s couch, and Claire tells her Nev has planned a “little holiday” in Majorca for them, “just until they cop him,” her rage at her sister is freshly ignited. Although she’s assured her boss that she’d go into hiding, she leaves the house, not willing to “sit on me arse watching fucking Telly” while “that bastard's still out there.” In this coming week’s episode it’s pretty likely that, as Sarah Lancashire teased in an interview, “It's time to let the dog see the rabbit."

I’m not sure why James Norton was chosen for the role of Tommy Lee Royce—I’ve tried to research that, but so far come up empty (I’ll keeping trying) but it was a brilliant choice. Audiences were getting to know him (and many falling in love with him) in Grantchester as the adorably sexy vicar everyone in the village wants to lead into sin. Tommy Lee Royce, capable of running his car back and forth over the broken body of a young policewoman, raping a gagged and terrified kidnap victim, and pouring gasoline over his own son with the deranged fantasy of setting them on fire together, is so far from Sydney Chamberlin that despite Norton’s distinctive good looks, many viewers had to ask if this was the same actor. (This season, Royce, whose hair and beard had grown long and Rasputin-like in prison, gets a haircut; when I posted a clip, one of my facebook friends exclaimed “Oh! There’s Sydney Chamberlin!”)

That’s a testament to Norton’s acting. But for those of us who recognized Sydney our lingering affection for the vicar—not to mention how gorgeous Norton is—also makes Royce a much creepier adversary. It makes it harder not to feel a tug of attraction for him, and that’s a far more insidious effect than a villain whose exterior is as repulsive as his evil inner life. Watching him get that haircut was almost like a strip-tease—which the show unabashedly exploited, showing us the whole thing from first swath cut by the electric razor to a bare-chested Royce preening in front of the mirror. For some viewers, his evil overpowered the erotic. For others (including me) it didn’t.

For Catherine, though, he’s simply the incarnation of pure evil, and she can’t even stomach the possibility that her daughter might have been attracted to him at some point (which of course doesn’t preclude the fact that he raped her.) And he’s just as intent on “fixing that policewoman bitch” as she is on…well, it’s not clear just how far she’ll go. That’s among the qualities that are most compelling about her. I guess we’ll see next Monday. In the meantime, I’m avoiding all reviews from Great Britain, where the series has already ended, and James Norton’sTommy Lee Royce has been voted the best villain on TV, winning the title overJodie Comer as Villanelle in Killing Eve, JR Ewing in Dallas (Is that still airing?), Sherlock Holmes’ nemesis Moriarty and Coronation Street serial killer Richard Hillman.

I’ll undoubtedly have more to say after next Monday’s US finale, so stay tuned, watch this space, or whatever metaphor for coming back to my substack appeals to you. Along with the finale of Happy Valley, I’ll be discussing the premiere of the second season of one of my favorite shows, The Bear.

Jay Newton Small, in Time magazine, insightfully wrote that while men’s shouting is seen as political passion, when women raise their voices “the specter of a punishing mommy rises up. It unpleasantly evokes personal memories of being scolded because we were “in trouble,” and makes us want to run away.

Perhaps it’s not coincidental that the same mantra appears in virtually every “defense” of Hillary Clinton. (“Admittedly, she was a flawed candidate,” etc.) On the one hand, it goes without saying—none of us is perfect. But then—on the other hand—why do they keep saying it? The reviewers have mostly been women. Are they so afraid of being viewed as “pc” feminists (e.g. the kind who voted for Hillary “just because she was a woman”) that they won’t come out and cheer for a powerful woman without gesturing toward her faults?

“The Most compelling female character on television” (Sophie Gilbert, The Atlantic, May 30, 2023)

A few more episodes in, and I’m noticing another thing I like about the Diplomat. It’s got a variation of the sassy-but-serious dialogue I liked about West Wing, but without the two things I strongly disliked about that show-- the sanctimoniousness, and (much worse) the sense that nearly every character’s voice was coming from the same writer.

What’s the point of having arms if you’re not going to wave them around?