Dr. Mel, Cassie, and “The Pitt”

Taylor Dearden shines a light on my daughter—and good writing.

“I’m neurodivergent so I think it’s [her portrayal of Dr. Mel King] really coming from me. I have severe ADHD. So we’re on the same spectrum now as autism, which was I think for all ADHD people was like, ‘Ohhhhh.’ And then all autistic people are like, ‘That’s why we got along with them.’ [B]eing on the same spectrum, it just feels, it felt right anyway.”

(Taylor Dearden, about bringing her own experience into the role of Dr. Melissa “Mel” King on “The Pitt”)

“When resident Dr. Melissa “Mel" King first appeared in The Pitt with her atypical body language and her enthusiastic if not entirely appropriate ‘I’m so happy to be here,’ I thought I knew exactly where her character was going. She’d be brusque but brilliant, filled with just enough savant-like insight to make up for her lack of bedside manner. We’d never get confirmation of an actual diagnosis, but she’d exhibit a number of behaviors and mannerisms that the average viewer might recognize as autism, ADHD, or a combination of the two that many people in neurodivergent circles have taken to calling AuDHD. These traits would probably be used for drama or comedic relief as necessary. A mix of House, Sherlock, Big Bang Theory’s Sheldon and countless other autistic-coded or “autistish” characters who came before her.

I’ve never been more delighted to eat my words.”

(Sarah Kurchak, “The Pitt’s Dr. Mel King Is a Small but meaningful Step Froward for Neurodivergence Onscreen,” (Time, April 11, 2025)

“Remind me again why we chose this job?”

“Cause we’re all ADHD and everything else would be boring as hell” (Patrick Ball as Dr. Frank Langdon speaking to a staff assistant on“The Pitt”)

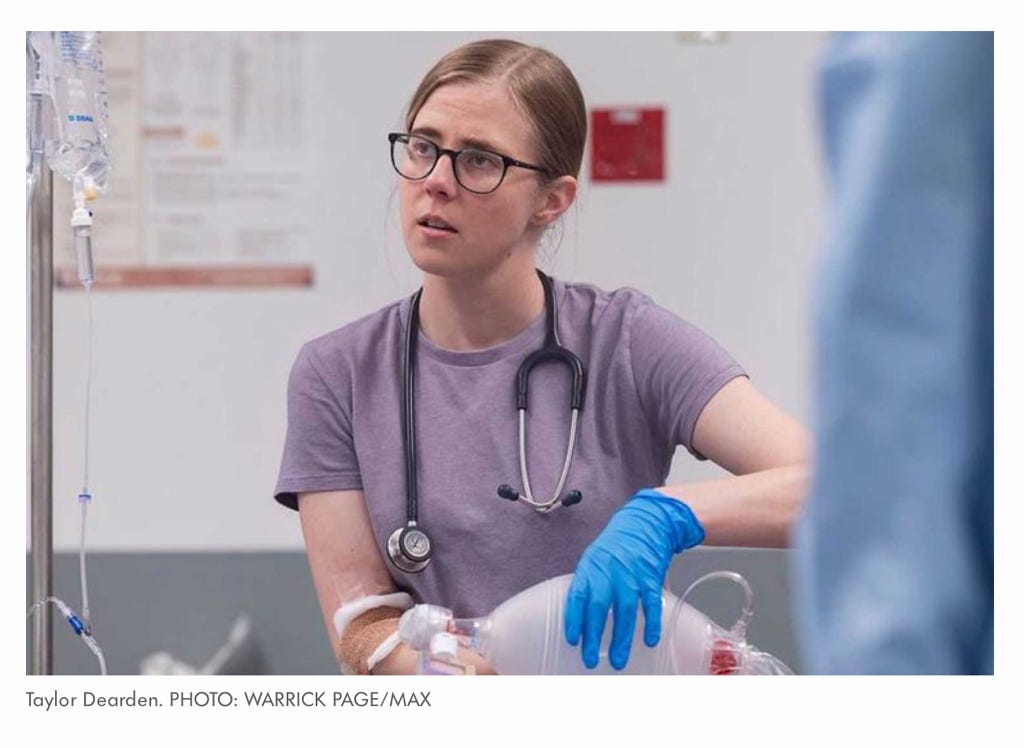

Dr. Frank Langdon may be joking, but there’s one character on “The Pitt” who is beloved by neurodivergent viewers everywhere. In part that’s because Dr. Melissa (Mel) King is not a caricature that shouts “on the spectrum” in every behavior. At the same time she is exquisitely, delicately recognizable by those who know. 1

Taylor Dearden, who plays Mel, won’t provide an interviewer with a specific “diagnosis” for her character. Other fictional characters that viewers have speculated are meant to be autistic or on the autism spectrum2 have been created according to a formula: emotionally distant, non-expressive, ostentatiously brilliant, their vulnerabilities hidden beneath a surface that other people mistakenly see as “cold.” Doctor King is none of those things, and it’s perfectly possible to not read her as neurodivergent. In fact, many reviews, despite Dearden’s own comments in interviews, do just that.

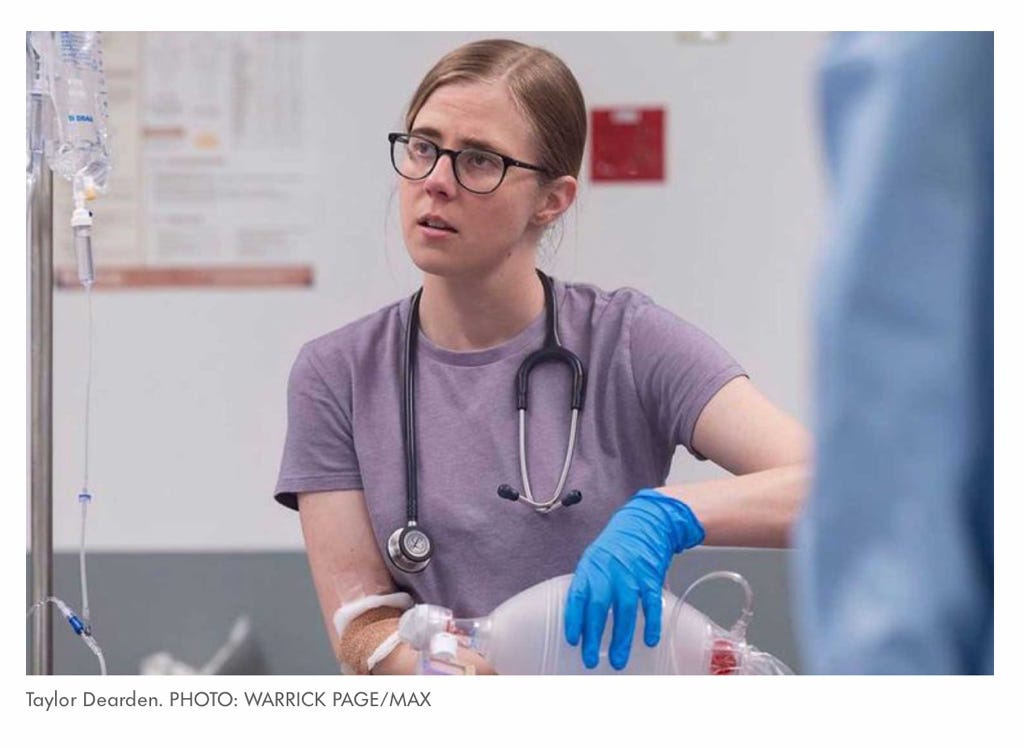

Dr. Langdon (himself a character that can’t be put in a neat box) gets Mel in a way that those reviews don’t. In one of my favorite scenes (written by Noah Wyle), after he’s complemented Mel on her sensitive and successful treatment of an autistic young man who has hurt his ankle and won’t allow Langdon to diagnose him, he offers Mel a task that lights her up. Watch the change in her face; hear the excitement over “a thousand??”

And don’t you just love how adorable (and happy) she looks as she puts on the light she’ll need to pick out all that gravel.

If you read my last stack, you know I’m besotted with Noah Wyle as Dr. Robby. In his approach to the characters in “The Pitt” (that he describes in the clip), he reveals what in my opinion is one of the secrets to the show’s success: As a writer, he doesn’t start with “plot” or preconceived notions (about, say, what a drug addict, or grieving parents, or an autistic person would do.) He starts with a conception of the whole person—and then lets that person be the guide as to what should happen. Wyle is embarrassed to use the term “vessel” to describe the writer’r role—but in fact that’s how some of the greatest writers work. Tolstoy, for example, revised a whole lot of Anna Karenina when he realized that he was more sympathetic to Anna than he was writing her. He came to see that when he began, conventional views of morality interfered with how he actually imagined and felt about the character. It’s the reason why a 20th (and maybe even 21st) century woman can still identify with Anna. (It also warns us not to identify the man with the writer. As a writer, Tolstoy was able to access an understanding—by becoming a “vessel,” by letting Anna speak to him—that he apparently didn’t have as a husband.)

There is no one version of “being neurodivergent.” And neurodivergence no more defines the whole person than my phobias (airplanes, tunnels, high bridges, medical procedures—and at one point in my life, I was agoraphobic) define me. But if I were creating a fictional character—“Susan Bordo”—she would be a lie if I didn’t include that aspect of being me. In the scene in which Langdon compliments Mel and gives her the “almost Zenlike” task of retrieving a thousand tiny pieces of gravel, we are given information about Langdon’s intuitiveness (and perhaps, his own ADHD, which he’d been jokey-glib about before) that is a truth about his character that we don’t see much of in other scenes. And when Mel’s face lights up—“a thousand pieces?”—well, there’s her ADHD in one exquisite, charming, perfect detail. A task that will still all the noise in my brain? That will provide the relief and pleasure of pure, illuminated focus? That I know I can do so well, so precisely? YES, I’ll take it, YES!!

At that moment, despite many differences in personality between Mel and my daughter, I saw Cassie. Cassie confidently putting together the complicated bird cages that are home to our cockatiels. Cassie seemingly instinctively fitting the dozens of parts to pieces of furniture that come with inscrutable directions that are supposed to make it “easy to assemble” but that Edward and I never can figure out. Cassie, whose mastery of the minute mechanics of screws and bolts, of the parts of horse’s bodies, of how to fix any number of things that have broken, constantly dazzles me. You have an order coming from IKEA? My daughter would be pleased to come and help you.

Cassie, unlike Mel (who, like all the other doctors, went through years of education), didn’t finish high school. From toddlerhood, she’d done everything “early,”—talked early, walked early, read early, picked up vocabulary at an amazing rate. But when, unsurprisingly, they put her in first grade in the “gifted and talented” section, she started to feel as though she was “different” (as she describes it) from other kids. Partly, it was due to factors unrelated to ADHD: her kindergarten teacher had been intent on “gender-normalizing” her into a sweet, well-disciplined girly girl and interpreted her preference for rough-housing with the boys as a kind of deliberate aggression.3But also, although she was a facile reader, in “gifted and talented” she started to dislike reading. “I was good at it, but I’d didn’t like having to do more of it.” She was bored by most of what they assigned (looking at the reading lists, I sure didn’t blame her for that) and couldn’t force herself to get through the boring parts. In fact, she began to find it hard to focus on anything that didn’t grab her attention.

I’d always been a reader, and couldn’t imagine a life without books as entertainment and solace. I understood not wanting to go to school (I was a chronic absentee myself) but I couldn’t wrap my limited imagination around the idea of a good life that didn’t involve reading, and my own anxiety led to a struggle between us, which deepened over a period of years. I didn’t “get her” anymore, and she didn’t get me, either. And I was always probing the “why” of it, which irritated and alienated her from me. I realize now that every time I asked her to explain, I made her feel even more “different” than she was already feeling. And besides, in those days she genuinely couldn’t explain it. It was just her, and rather than accept her as she was—something that was easy for me when it came to other aspects of her personality (like her gender not fitting into the boy/girl box)—I acted as though “not liking reading” made her an alien life form.

I was stupid. But not as stupid as the first psychologist we took her to, after she started high school and began to withdraw from everything—even the other girls who rode horses with her at the farm, who’d begun to cluster in circles between rides, chatting and laughing while Cassie hung at the periphery, silent and apart. She deeply wanted their friendship. But they too had become a boring book she couldn’t get into, didn’t know how to get into.

My older sister was a therapist who frequently treated children, and she had suggested we have Cassie tested for ADHD. We didn’t live near enough for her to be familiar with medical resources here, and I didn’t do enough research on my own, so I didn’t chose well. This guy’s diagnosis, after a battery of tests that I later learned were outmoded and limited, was no, no ADHD, she was too smart.

He was an idiot.4 (We ultimately did have her properly diagnosed, by a much more perceptive, up-do-date therapist—my own!) But the tests the first psychologist gave her did reveal something interesting. The most striking thing that had come up, he said, was how anxious she was to please other people, and how fearful she was about disappointing them. So many teachers, over the years, had seen her as sullen, uncooperative, even belligerent5they would have been surprised at that finding. I knew otherwise. Cassie was a person who, after she started to work at a farm, sat on the stairs, crying uncontrollably, so hard she was unable to breathe, because she had overslept and would be a few minutes late. “Jan will hate me, she’ll hate me,” she sobbed.

What many of Cassie’s teachers—and those fictional depictions of dour, blank-faced, anti-social savants—apparently didn’t know was that many people with ADHD also suffer from RSD (Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria.) I’d never heard of it myself until I read about it in in

’s stack. I tend to be suspicious of the proliferation of syndromes and disorders, but the description Bentley-Quinn gives, from Joanne Steer’s book Understanding ADHD in Girls and Women, immediately synched with my knowledge of Cassie:“...RSD is a form of emotional over-reactivity and is described as the exquisite sensitivity to teasing, rejection or criticism, or the individual’s perception that they have fallen short of what was expected, whether this perception is real or imaginary. Provocation of RSD appears to result in either an attack of rage against the person that has triggered it, or an episode of profound low mood, usually accompanied by the physical sensation of having been wounded…” (p. 224)

I’m not interested in a debate about medical diagnosis, classification and nomenclature. I know very well how it varies over culture, history, and medical fashions. My panic disorder, which descended on me shortly after my first marriage, was chalked up by therapists to “inability to accommodate to the feminine role.” Those who were more biologically-minded treated me with anti-psychotic drugs that dried my mouth and clogged my mind (the part of me I needed most to save me.) In those days, too, most medical professionals didn’t think in terms of spectrums but individual “pathologies” that were often theorized inadequately: “Autism” was identified with the most extreme ends of what we now know is a range of neurologically atypical behavior and experience. ADD, which we now think of as manifesting itself in a variety of ways, was reduced to “hyper-activity” and generally thought to only affect boys. We didn’t conceptualize eating, body, and weight disorders in terms of a continuum, but focused on (a limited idea about) “anorexia” whose diagnosis requested self-starvation, emaciation, and seeing yourself as fat no matter how skinny you got. And so on.

So I don’t know how I feel about the classification of “RSD” as yet another category in the growing list of contemporary “disorders.” What I do know, however, is how difficult it is to talk my daughter down from the ledge of despair and self-castigation when she believes that she “has fallen short” in some way.

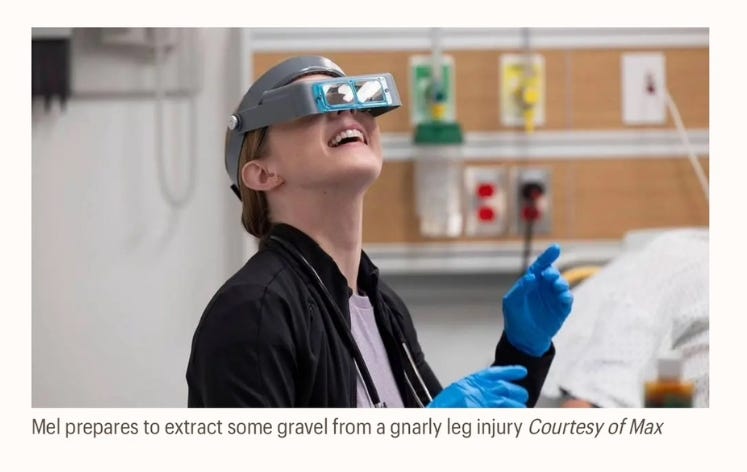

All the doctors in “The Pitt” are highly critical of and inclined to blame themselves when things go wrong. Young Dr. Whitaker (German Howell) is distraught when patient after patient dies on him, although none of them are the result of mistakes he’s made. Dr. Robby is tormented, years later, second-guessing the choice he made when his mentor was dying of complications from COVID. But Mel questions herself even after she’s performed a successful procedure—and then, on top of that, worries about her emotional reaction:

Langdon: You OK?

Mel: I am - I get frustrated when I can't do things or at least it looks like it.

Langdon: Yeah, you and me both.

Mel: Thanks, but my frustration manifests itself emotionally, and then I get upset. And then it looks like I can't handle things. And, you know, then I can't cry in front of the patient 'cause no one wants to see their doctor cry. That's just a big red flag.

Langdon: Well, you just did a perfect crike.6You're doing great.

“There is some weird part of the ADHD brain that clicks into the perfect emergency person.” (Taylor Dearden)

When she was in third grade, Cassie’s class had a field trip to a Native American history fair up near Red River gorge. One of the “hands-on” exhibits was a deer that the children were given instructions in skinning and then had the opportunity to do themselves. While the other little nine-year-old girls ran away, pretend vomiting, Cassie eagerly stepped up. People who hunted for survival had done it on that land for centuries; why would she turn away from it? She just didn’t get what the problem was. Now, at 26, there’s no kind of animal injury or illness, no procedure that the vet needs help with, no matter how bloody or gruesome, that she runs from. If she’s needed, she’s right there.

She’s right there—if it has a purpose, and it’s clear to her what that purpose is and what she needs to do.

I once asked her if she’d ever dissected a frog at school—something that was part of the science curriculum when I was growing up and that I avoided by employing my thermometer-on- the-radiator trick. She said they hadn’t been expected to do that, but surprised me by saying she wouldn’t have been willing to. “What purpose would it have had?” she asked. Cassie had cut open a dead sheep without any squeamishness because it was already dead (of a heart attack in transit to the farm) and her co-workers, who had large families to feed, could use the chops. Cutting up an already-dead sheep had purpose; pinning down and cutting open a squirming frog just so some kids could see its innards for real did not.

Cassie felt the same way (“what for?”) about pretty much everything they were expected to do in school, both curricularly and socially. It was “so much effort,” she told me, to figure out what other people were really thinking or wanting (“I don’t like having to read between the lines”) and when it came to conventional expectations of girls, she couldn’t see the point of most of it. She did great on standardized tests (she mostly just guessed; “those things are pretty predictable.”) but if asked to write something, would produce as few sentences as possible. When I asked her a few days ago the way her ADHD figured into her dislike of reading (we now can talk openly about these things) she objected to the term “dislike.” “It’s not that I dislike reading; it’s that there’s always so much extra in there that doesn’t need to be, and I can’t concentrate on those parts.” I asked her for an example from high school, when her “academic” life pretty much crash and burned. She said Pride and Prejudice. “See, I really liked the plot and the characters. I liked the movie. But in the book there were all these parts that didn’t seem to have a purpose and that I couldn’t concentrate on.”

We are a mixed-bag of a family in so many ways: Christian and Jewish, white and Black, oldsters with a daughter young enough to be our grandchild. My husband, who teaches Russian literature, adores exploring just those details that Cassie finds excruciatingly boring. I’m somewhere in-between. Like Cassie, I grow impatient with too much description of things that don’t interest me and skipped over many passages of War and Peace (though none of Anna Karenina.) But the books that I loved growing up had given me much pleasure and solace and hope, and when I wound up in a field—philosophy—that demanded a lot of boring reading in the service of “ideas,” I stopped expecting pleasure from reading. And then, too, I don’t have ADHD.

I didn’t realize in the years that Cassie and I were at odds about reading that at the same time she was quietly absorbing all the knowledge and skills that did make sense to her, that did “have purpose” for her. When she was sixteen and got her learner’s permit, she astounded her father and me by immediately knowing how to drive—stick shift!—without one lesson. “I’ve just been watching you guys,” she told us. As I mentioned before, She can pretty much put anything together without reading the directions. She reads the world with the eyes of a mechanic: she knows what parts will fit and what parts won’t, just by looking. And she’s a wonder in an emergency.

In that way, she’s much like “The Pitt” doctors. They may be worrying about something in their personal lives, they may be injured themselves, they may—like Dr. Robby—be on the verge of emotional meltdown. But the ambulance or the stretcher arrives, the switch is flipped, and they spring into action to do what is required. Cassie once had to carry a stillborn horse to her truck, drive to the morgue, and then bring the body into a room with dozens of other dead horses. “It had to be done, so I did it,” she said. There’s no kind of animal injury or illness, no procedure that the vet needs help with, no matter how bloody or gruesome, that she runs from. She was right there, too, when a visiting dog brutally attacked our Havanese Sean. I ran from room to room, mopping up the blood that was all over the floor and crying hysterically. Cassie grabbed a towel, wrapped Sean in it, and was immediately off to the emergency animal clinic. Her presence of mind, her ability to rise to the (horrifying) occasion, to put her own feelings to one side in order to do what was required, amazed me. (Sean survived.)

I used to think of this as the result of working on a farm for many years. But in fact, Cassie has been that way all her life. Still, it surprised me when in an interview Taylor Dearden, describing the arc of her character’s growing confidence over the course of the season, said the ability to rise to the demands of emergencies is “a very real ADHD thing.”:

“We are just amazing at emergencies. Something in our brain clicks. We can do things that we read about once freshman year. All of a sudden, we can pull it out. This is an actual medical thing. We are overrepresented in emergency departments and firefighters, because there is some weird part of the ADHD brain that clicks into the perfect emergency person.”

I asked Cassie what she thought that “part of the ADHD brain” that was so perfect at emergencies, and she immediately had an answer for me, as though it was something she’d already thought about and figured out for herself. “Our brains are always going a mile a minute, taking in everything, including what might happen if this thing happens, or if that thing happens, of what’s probably going to happen. So for example, when Sean got hurt, the whole sequence of what I had to do came into my brain: first thing, get him out of Enzo’s mouth [she laughed a little here], then wrap him in a towel while telling mom to call the vet emergency room, then….etc. etc.”

That made so much sense to me. And so did Taylor Dearden’s comments about how overwhelming this constant flood of information can be:

“The thing that is never shown, that is definitely most of the difficulty I have with my neurodivergence, is overwhelm. I won’t be able to have the right intonation on this sentence because I’m overwhelmed; we get angry or whatever because of being overwhelmed, usually.

Things are happening in our heads so much faster and more intensely than everyone else that it’s hard to be able to focus on how it comes out of your mouth when you’ve got eight billion other things going. Our brains are working way faster.”

Dearden sometimes had to wear special noise dimming earplugs, because too much was happening on the set of “The Pitt.”7 Edward and I can be having what he and I experience merely as an excited, perhaps slightly argumentative conversation and Cassie will suddenly leave the room and go upstairs to her room; for her, our debate had filled the room with too many pieces of ideas, too much emotion, too much stimulation.

“What if I don’t have a special sauce?” (Dr. Melissa King)

“I pay attention to the whole of them.” (Cassie Lee)

In one episode, Mel is walking with resident Dr. Samira Mohan (Supriya Ganesh, who actually has a background in neuroscience,) who Robby had nicknamed “Slow-Mo” because of the amount of time she spends talking to patients. They’ve been discussing who has what kind of “special sauce”—or particular skill or talent—as a doctor:

Actually, Mel’s special sauce is already apparent. She may be socially awkward in conventional situations, but she has an emotional intelligence that goes beyond empathy in her ability to calm and soothe in the particular ways that individual situations call for. In one episode, Langdon is frustrated by a man—Terrence—with a sprained ankle who resists having a standard evaluation done. He tells Mel about it, who looks at the patient’s chart and notices that he is autistic. “Let me try,” she tells Langdon.

As she enters the room, she shuts the door and dims the lights. “Pretty bright in here!” She says, reducing the sensory input but in the most casual way, as though anyone would find it too bright. Instead of asking questions about the ankle itself, she asks Terrence what “worries him” about the pain, and when he tells her that he’s worried he won’t be able to compete in his first table tennis tournament she affirms rather than minimizes his concern: "Wow, that's a big deal.” After she’s arrived at a diagnosis, she illustrates it to him calmly and clearly to him on an IPad.

When Langdon asks her how she did it, she tells him she has an autistic sister. And it’s true, as Sarah Kurchak comments, complimenting the show, that “there’s a lot of genuine understanding of autistic people packed into” that brief scene. But Mel’s capacity to enter another person’s world goes beyond her familiarity with autism. Wanting to give a little girl—Bella—the opportunity to “speak” some final words to her older sister Amber while shielding her from the terrible fact that Amber has died from drowning, she uses a teddy bear as a messenger. "Since you can't see Amber right now, I bet you've got a lot you've gotta tell her," she says to Bella. "Bear is going to help. You tell Bear everything you wanna tell Amber, and I'll take Bear and sit her on Amber's pillow." Bella thinks it’s a great idea. And it is. But the inspiration for it doesn’t come from anything specific to Mel’s having an autistic sister; it comes from Mel’s ability to channel her deeply empathic imagination of how it is to be in the world of another person into her approach to treating them.

Is this empathic intelligence connected to her neurodivergence? I don’t know. I do know that it’s virtually identical to how and why Cassie is so phenomenal with horses.

Working with horses is what made things click into place for Cassie. She not only knows just about everything there is to know in “normal” ways (horse breeds, physiology, disorders, training methods, etc. etc) but seems to be able to understand everything a horse is feeling, wanting, or afraid of. And the more “difficult” the horse, the bigger the challenge, the more she is drawn to them. She understands—deeply understands—that what gets seen by some as willfully disobedient is just the struggling nature of a special, wild being in need of being understood and loved for exactly who they are.

“What makes you so good at that?” I asked her.

“I try to imagine what they are feeling and thinking. I pay attention to the whole of them,” she said.

That’s Dr. Mel’s special sauce too.

That’s true of Dr. Robby’s Jewishness, too: It’s undeniably present, an important part of who Robby is (in some ways that will be most recognizable to other Jews.) But his individuality isn’t swallowed by familiar stereotypes. See my stack on Dr. Robby:

Doctor Robby

1. When he played John Carter in “ER,” he was not my type. He was not just too baby-faced, he was also too “cooked” (referencing Claude Levi-Strauss here): too smoothed out by civilization, good manners, rule-following. I went for the more “raw,” surly, often ethnic types. In “ER,” that would have been Eriq LeSalle. In earlier doctor shows, it would have…

Such as (among female characters): forensic anthropologist Temperance “Bones” Brennon (Emily Deschanel), detective Elise Wassermann (Clemence Poesy) of “The Tunnel” (based on Sonya Cross—played by Diana Kruger— from the original Swedish series, “The Bridge”), chess wizard Elizabeth “Beth” Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) of “The Queen’s Gambit”, Elizabeth Zott (Brie Larson) of “Lessons in Chemistry.”

I’m fairly sure that race figured into this, too. She dressed and looked, not just like a boy, but like a little Black boy.

We ultimately did find a more attentive, perceptive, up-to-date therapist for her, who diagnosed her properly. And since he happened to be my own therapist, he helped me too!!

Not all of them. Three in particular—Lauren Rister in second and fourth grade, and Michelle Rasmussen and Sam Arnold in high school—were wonderful with her, and she loves them to this day.

In medicine, "crike" or "cricothyrotomy" refers to a surgical procedure where a hole is created in the cricothyroid membrane to establish a breathing passage in emergency situations.

“It's a very tough show for neurodivergents to be in,” she says. “It moves really fast. It's really hard words. It's actions we just learned. You have to put all of that together at the same time and as quickly as possible. And we go so quickly, we don't have much time to take a second to review, to calm down. And so it's definitely a challenge to shoot.”