A Complete Fiction: Suze Rotolo and the Woman Problem of “A Complete Unknown”

Changing her name, apparently, gave them license to turn a real woman into the fiction that Dylan was most comfortable with.

This is not a movie review. This is about mythology. This about how the male gaze seduces us with pleasure, and hides itself behind art. This is about the eclipse of real women. This is a protest song.

Bob Dylan, 1960-65. There are many ways of telling that story. Read the books, watch the documentaries, you’ll see just how many there are. A Complete Unknown chooses a story focused on Dylan’s trajectory from young Woody Guthrie worshipper freshly arrived in New York, through his emergence as a “folk” singer/songwriter, difficulties dealing with escalating fame, and famous/infamous turn at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where he “went electric.” The movie is selectively (and inventively) based on Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties.

Roughly following Wald’s book allows the development of Dylan’s music to dominate, and that alone makes it a phenomenally entertaining movie. But it also puts the movie in the genre of the brilliant, enigmatic genius narrative, and that creates a challenge: What do you do with all the other people in his life? Writer/ Director James Mangold says he imagined it as an “ensemble” movie:

I didn’t want to turn Bob Dylan into a simple character with a simple thing to unlock that then makes you go, “Ah, now I get him.” I don’t think that’s possible, having gotten to know him. I also think it’s pretty clear he spent most of his life trying to avoid that exact act by anybody. Which is an act of, by nature, reduction — reducing someone to a simple epiphany, a plot-point Freudian history of their life….

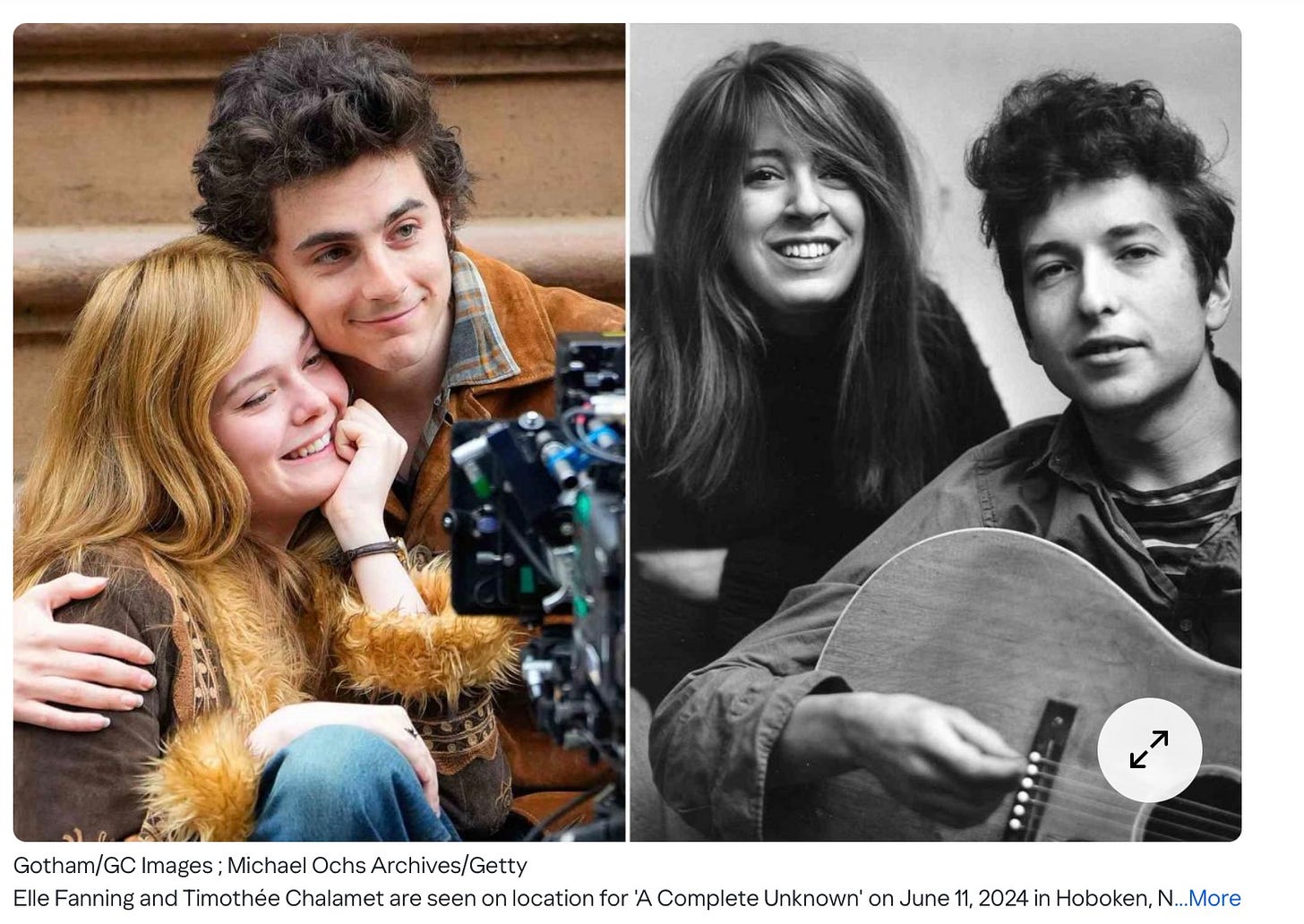

…So when I say it’s a strong ensemble piece, it’s certainly following Bob, but I’m much more interested in the wake that this person has left on others, as much as I’m interested in unpacking who he is in some kind of conventional movie-Freudian way. That’s why Elle’s character and Pete Seeger, Edward’s character, and Joan Baez, of course, and many others are more than just passing through in a kind of Hall of Presidents pageant. They’re significant players coming in and out of the movie. They all were instrumental in his journey in the years between ’61 and ’65, but they all also interacted with him in different ways that are prisms and keyholes to different aspects of who Bob might be.

Mangold actually collapses two different goals here: One is exploring “the wake that this person has left” on the important people in Dylan’s life (how Dylan has effected those around him): the other is other characters as “prisms and keyholes” revealing “different aspects of who Bob may be.” Neither can be done convincingly, though, without a better-than-superficial picture of the people in Dylan’s life. And that’s where A Complete Unknown, as entertaining and stirring as it was for me, left me feeling angry in a way that’s all-too familiar.

Pete Seeger: a fully realized character for whom a great deal of preparation had clearly been done, both by the writer and by Edward Norton, who plays him.

Joan Baez and “Sylvie Russo”: no.

In the case of “Sylvie Russo,” so much “no” that I would go as far as to say she’s a complete fiction. Or maybe “fantasy” is more like it.

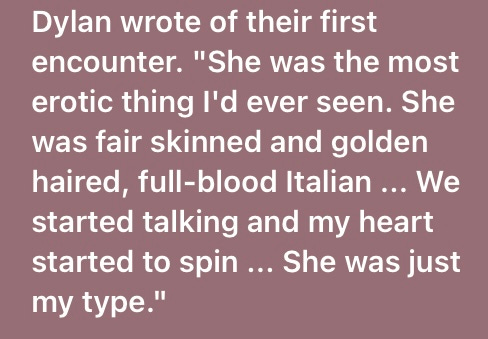

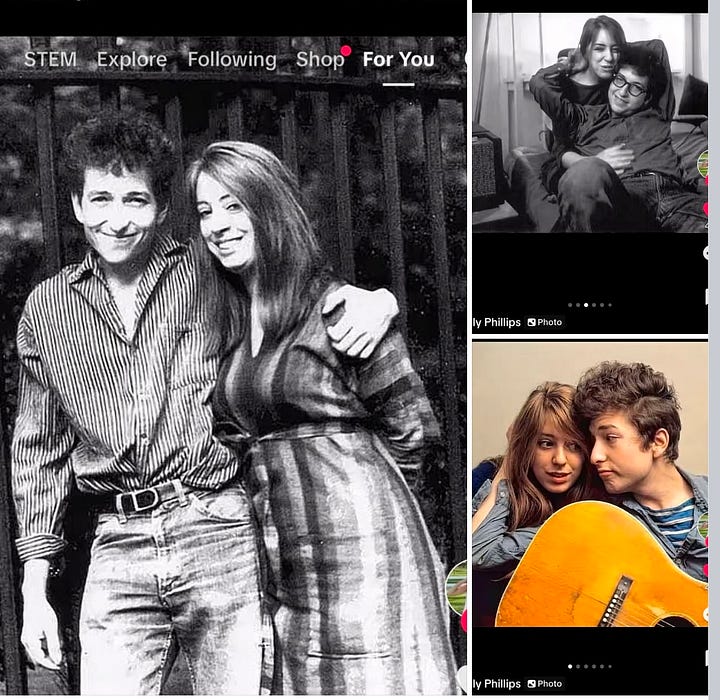

It’s Dylan’s fantasy, first and foremost—he was pleased with the script, and even did an acting-out run-through of it, playing himself. Dylan was the one, too, who asked that Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s on-and-off-again girlfriend for much of the period covered in the movie, and who famously appears with him on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” (I was so envious of that girl, walking arm and arm with him in a snow-covered NYC!) be given a pseudonym in the movie. His reason, as Elle Fanning, who plays her, recalls:

“Bob talked to Jim a lot about the script, and the one thing he wanted was that Suze’s name be changed in the script because he felt like she wasn’t a public figure. She always wanted to remain a private person. I really held that in my heart, the gravity of Bob’s choice, because they had stayed close until she passed away in 2011”

Mangold elaborates:

“[Rotolo] was the only one who wasn’t a celebrity and an icon in and of themselves with a kind of public persona. Everyone else is up for the gauntlet and has been in that game a long time….And there was just a feeling for Bob of not subjecting her to that. But certainly the character Elle plays is that energy. There’s no real decoding to that other than just not feeling like there was value in subjecting her real name to the same kind of spotlight that these other people in the movie, who all lived their entire lives in the spotlight, experienced.”

This justification—respect for Rotolo’s privacy and tender concern for keeping her “out of the spotlight” (even though she died in 2011)—has been accepted by every reviewer and interviewer:

It’s true that Rotolo wasn’t a celebrity. But she was “public” enough to have written a book about her life with Dylan, And—surprise!—far from the film “representing her in all but the name,” Rotolo tells a very different story about their relationship than that depicted in A Complete Unknown. (Rotolo’s account is also corroborated in Anthony Scaduto’s Bob Dylan, which contains extensive interviews with friends of both Suze and Bob, as well as Dylan himself.)1 Did Mangold not read Rotolo’s book? Or did it complicate the picture that Dylan was comfortable with? Either way, Suze Rotolo’s experience and insights—not just her name—were erased. And instead of providing a “keyhole” into Dylan, this shut the door on aspects of his personality that are central to understanding him. So whether you care about how women are portrayed—in the typical film about the great, singular male genius, pretty thinly and carelessly (Oppenheimer is another example)—or are only interested in Bob Dylan, this is a place where the movie badly lets us down.

“Sylvie Russo”

A young man who is bound for glory comes to the big city, where his genius is immediately recognized, not by everyone at first, but by those who matter, those who know. They are stunned, captivated, they can’t look at the young man except through dazzled eyes. Along the way to fame, he meets a girl—pretty, political, smart and fun. They go to see “Now Voyager,” and the young man corrects the girl when she describes Bette Davis as having had to leave an abusive home to find herself. “She just made herself into something different,” he says. The girl doesn’t argue.

Bob and Sylvie seem to become girlfriend and boyfriend. But pretty soon, she’s off to Italy “on a school trip.” For a minute, Bob sulks about her going, but it doesn’t last long, and while she’s gone he writes a lot of songs. Powerful songs, songs that are poetry and protest and personal and political.

The Cuban missile crisis happens, people are frantic and fear the bomb is coming and Bob goes to sing in a club. “All are rapt” (the directions from the script reads) as Dylan “plays and sings lyrics from a scrawled-over dinner placemat.” One of the rapt listeners is the beautiful and famous Joan Baez, who kisses him deeply and passionately as they exit the club. In the morning, he criticizes her songs, she calls him “kind of an asshole” and he writes one of his most celebrated songs. (The whole incident, beginning to end, is invented.)

Sylvie returns from Italy and intuits what’s been going on in her absence, and mostly disappears from the story while Bob and Joan work on songs together, and she helps him become famous too.

After Sylvie and Bob break up, Silvie—who is vaguely connected to the art scene and a painter of some sort, who knows, it isn’t made clear—seems to be getting on with her life. But that’s an illusion. Whenever Bob reappears, she’s ready to hop on his motorcycle and join the circus again. Eventually though, it gets to be too much, as she realizes she’s been displaced by Baez. She’s been aware of the relationship, but now, watching them perform together at the concert that represents “the night that split the sixties,” it finally hits her in the feels. Her “eyes fill with tears” and she runs off. (“I can’t do it. I thought I could but…”)

Discovering she’s gone, Bobby chases her down as she’s about the board the ferry, and they talk.

From the script:

SYLVIE It was fun to be on the carnival train with you, Bobby. But I think I gotta step off now. I feel like one of those plates, you know, that the French guy spins on those sticks. On the Sullivan show.

BOB That a bad thing? I like that guy.

SYLVIE I’m sure it’s fun to be the guy, Bob. But I was a plate.

[Bob sighs, looks off. Sylvie touches Bob’s fingers through the fence. The ferry whistle blows.]

SYLVIE: Don’t ask for the moon, Bob. .. We have the stars.

There’s a ton of invented stuff here—not just the incredibly hokey reference to the line from Now Voyager, but more significant historical details (Joan Baez wasn’t even at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival)—but I’m not interested in fine-toothing the script’s departures from what happened that particular night. (There’s at least a half dozen different accounts of the reactions to Dylan’s “going electric” in the second half of the show.)2

What interests me are not the little inventions (every “historical” drama or biopic has them, and even the documentaries construct “what happened”—through selection, emphasis, narrative arc, etc.). What interests me—and frankly got me madder than hell—is how differently, in her own book and in the accounts of others, Suze describes herself, the relationship, the reasons for the break-up, and Dylan himself. None of it is bitter or angry; actually, and unlike some of Baez’s recollections, she’s remarkably warm and affectionate towards Dylan, quirks and all. But Suze and Sylvie are far from the same person “in all but the name.”

Suze Rotolo

The following description, from Anthony Scaduto’s book, will surprise no-one who knows anything about early 60’s culture, it’s glorification of male politicos, leftist musicians and rebel-movie stars, and the subservient role their girlfriends and wives were expected to play:

“Bob Dylan was totally possessive about his women, a trait that seems common to many artists and entertainers. One noted super-groupie has put it this way: "A woman who loves a musician has to reconcile herself to the fact, right up front, that she must come second to his music, that his music is the most important thing in his life. It takes a special kind of chick to be able to do this, to want to become almost a slave."

What may be more surprising is the sentence that follows: “Suze was not about to become that sort of vegetable. She didn't simply want to hang around being Bob Dylan's woman, completely swallowed by him and his career, even as she loved him.” In her book, Suze is clear about how much she adored Bob, and in informal pictures they cavort and cuddle like puppies who can hardly bear to not be close. But in the book, Suze also craves independence—and it’s her still-inchoate but gradually crystallizing need for autonomy—her pre-feminist feminist stirrings—that led ultimately to the end of the relationship, not another woman.

From Suze Rotolo’s book:

There was an attitude toward musicians’ girlfriends—“ chicks,” as we were called, or “old lady,” if a wife—that I couldn’t tolerate. Since this was before there was a feminist vocabulary, I had no framework for those feelings yet they were very strong. I couldn’t define it, but the word chick made me feel as if I weren’t a whole being. I was a possession of this person, Bob, who was the center of attention—that was supposed to be my validation…Make the coffee, serve the drinks, sit down and listen, was the tune. The side effects of this scenario made for feelings of insecurity and doubt, which snowballed into dissatisfaction and unhappiness that were difficult to articulate. I couldn’t find my way with anyone, really. Everything was centered on folk music, which was fine, because music was a big part of my life, but it wasn’t my life’s work. The politics of the time were what we all had in common, pretty much, but no one was choosing politics as a profession. Politics were the foundation upon which many other things were built. But I was also interested in the theater, where I was involved with productions that were breaking new ground, and curious about art that was erupting into something no one except Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, perhaps, could have foreseen. I was very young, I was still forming myself, but I did know I wasn’t a musician, nor was I a musician’s “chick.” And you could bet the neck of a Gibson I had no desire to graduate to “old lady.”

…..I chafed at the notion of devoting my young self to serving somebody, since I was still curious about life—questing. I hated being thought of as so-and-so’s chick: I did not want to be a string on Bob Dylan’s guitar. Because I was with my boyfriend didn’t mean I had to walk a few paces behind, picking up his tossed-off candy wrappers. But I didn’t know where to put that frustration. This was before the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, when many of these issues were articulated. I resented not being able to wander off by myself and sit in a café to draw, read, or write the way the guys could, without getting hit on.

Bob, however, was having none of this “wandering off by myself”: "He won't let me do anything," she told one friend. "He just wants me to hang around with him all the time. I had to stop working now that he's making some money, and he doesn't want me to do anything for myself. I have to be myself, too, but he can't understand that."” (From Bob Dylan by Anthony Scaduto)

Suze did not go to Italy because of some vague “school” thing. She went at first to travel with her aunt—but stayed in order longer to study Italian in Perugia, and to remain away from Dylan and his incessant needs. “Bob was charismatic; he was a beacon, a lighthouse. He was also a black hole. He required committed backup and protection I was unable to provide consistently, probably because I needed them myself. I loved him, but I was not able to abdicate my life totally for the music world he lived within.” (Rotolo)

After she’d gone, Dylan was both furious and bereft—none of which we see in the movie. Mikki Isaacson, a close friend of his, recollects:

“He was totally down after Suze left. Kind of lost. He wouldn't come near the rest of us in the beginning. You'd meet him on the street and he wouldn't respond. Physically, things began to happen to him. He didn't eat and he was neglecting himself. He got scruffier looking─back in the beginning, when he looked scruffy, he was at least clean. He showered a couple of times a day. But after Suze left he began to really look dirty. He started drinking, too, after she left. And there were all kinds of rumors about drugs, but he wouldn't talk to us about it. We were all trying our best to keep Bobby together. I know he was falling apart at the seams. His performances began to fall below his usual stuff. He'd get up on hoot nights at Gerde's and he would be bad. He was so depressed we were afraid he was going to do something to himself. People would stop each other and say, 'Have you seen Bobby? What's happening to Bobby?'"

“What’s happening to Bobby” was not a passionate affair with a smitten Joan Baez, dazzled by his performance the night we all thought we might be blown to bits by a bomb-carrying missile. “What’s happening to Bobby” was that he was falling apart, writing love letters to Suze, begging her to come back home. And Suze, on her part, was making some connections:

“While in Italy I read Françoise Gilot’s memoir, Life with Picasso. I expected to learn about Picasso, an artist I loved, but instead the book turned into something entirely different. It made me think about Bob. I forgot all about Picasso. I felt I was reading a book of revelations, lessons, warnings. Even though Picasso was a much older man than Bob and had experienced a lot more, their personalities were so similar it was astounding. Picasso did as he pleased, not worrying about the consequences for the people around him or the effect his actions had on them. He took no responsibility, clarified nothing, came to no decisions and did nothing that would have made it possible or easier for the various women he was involved with to leave him and get on with their lives. He was a magnet, and the force field surrounding him was so strong it was not easy to pull away. His art was the main function of his life. At the end of his arm was a brush.

I was floored. The same feeling kicked in that I had felt in New York: that men could always have it both ways. They were born into a society that gave them permission to do as they pleased. Women, on the other hand, were sidelined. And for the male artist (Picasso, Bob) it didn’t matter what others expected or felt or thought of them or their work; they just did it.” (Rotolo)

Among the songs that Bob wrote when Suze was away from him were “Boots of Spanish Leather” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe.” Dylan described “Spanish Leather” as “girl leaves boy." In the dialogue of the song, he explained “the girl who is sailing away asking whether she can send him anything when she gets across the sea, and the boy insisting he wants only her return, "unspoiled," asking that she comes back with her "sweet kiss." And then he gets a letter from her, written on the ship, in which she says she doesn't know when she's returning and her words make him feel that her "mind is roamin'.And, he says, you can send me boots of Spanish leather.”

As for “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” although it is always interpreted as Dylan insisting on his freedom from his lover’s demand for all-consuming love and attention—the rebel male trope that intrigued Dylan and that he nurtured throughout his career—a remark of his makes me wonder whether “It Ain’t Me, Babe” isn’t an inversion of his own need for Suze. “It’s not a love song,” he insisted when confronted with that interpretation, “It’s a statement to make me feel better.” (Scaduto) To make himself feel better Dylan becomes the one calling the shots in the fantasy inversion of the relationship. In reality, he was tormented by Suzy’s independence from him, his inability to tie her down.

Reading this remark brought into focus what the main distortion of the movie—Suze/Sylvie as the love struck, abandoned, heartsick girlfriend who finally “had it” only because she saw that Dylan was in love with someone else—obscured about Dylan that every woman who met him saw at once: He was a baby who needed the unconditional love of a mother more than a life partner. “To everyone else, on the surface,” Scaduto writes, “ he was the ultimate cool. But with Suze he would break down as a youngster might, shouting and screaming and crying─crying constantly─overwhelming her. He'd sit in a corner with her and whisper: ‘Hey, it's me and you against the world,’ and, one friend says: ‘She was unable to work or paint, when Dylan was around….and they'd spend much of their time watching an old TV set someone had given them. Only occasionally, when Dylan would leave for a few days to do a brief campus tour, would she be the old Suze, gay and busy and chatting with delight about everything around her.” But even then, he telephoned constantly. ‘It was like an addiction,” Suze writes, “he needed to know I would be there for him and I would be, in spite of my attempts to do otherwise.”

The heartbreak over another woman trope, which the film saddles (the now decidedly wholesome, non-erotic, non-ethnic-looking) “Sylvie” with leaves Dylan’s masculinity intact, as does his callous, asshole behavior with Baez. Being exposed as a petulant, bawling child would not. Which may be why Dylan was satisfied with the film, happy to have the real Suze eclipsed by a heartbroken “Silvie,” her eyes filled with tears, quoting from the corniest line in a very corny old movie.

When Dylan finally did marry (to Sara Lownds) it was to a woman who, he freely admitted, “will be there when I want her to be home, she’ll be there when I want her to be there, she’ll do it when I want to do it. Joan won’t be there when I want her. She won’t do it when I want to do it.” Being demanding, ordering ones old lady around is manly. Having ones soft underbelly exposed is, arguably, something Dylan has fought against all his life. In his memoir, he has little to say about his break from Suze: “Eventually fate flagged it down and it came to a full stop. It had to end. She took one turn in the road and I took another.” Better to say not much of anything than to admit that you once were deeply in love with a woman (“a child I’m told”—Suze was 17 when they began together) who refused to be at home when you wanted.

P.S. Although in this piece I haven’t discussed Baez or other characters and events depicted in the movie, I did do a huge amount of research for this piece. When I realized it would be way too long to include everything I’d planned to write about, I pared my ambitions down to the focus of this piece. I’d be delighted, though, to answer any questions or have any conversations you’d like about the movie, the persons, or the sixties. Just don’t expect me to know about chord changes.

Another invaluable resources is

’s , My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me ) Thal was Dylan’s first manager, and has a first-hand, insightful understanding of Dylan and the people in his life, including Suze and Dave Van Ronk, who barely appears in the movie but has a great deal to say in Scorcese’s documentary “No Direction Home.”As Wald describes: “Some spectators recall the crowd exploding in boos, some recall cheers, some only shocked silence. There are stories of Seeger striding the backstage area with an axe, threatening to cut the sound cable, or huddled in his car, in tears, unable to face the death of his dream. Some recall Dylan in tears as well, ending his set early and disappearing while the crowd screamed in anger or disappointment and Yarrow begged him to return, then finally coming back onstage, contrite or defiant, with an acoustic guitar borrowed from Yarrow or Johnny Cash, to sing a wistful or bitter farewell. Some recollections can be confirmed or disproved—Dylan played a particular sequence of songs and was on and off stage for measurable periods of time, and some of the crowd noise was caught on tape—but there were upward of seventeen thousand people in the audience, with every seat and space on Festival Field filled and another two to four thousand listening from the parking lot. What anyone experienced depended not only on what they thought about Dylan, folk music, rock ’n’ roll, celebrity, selling out, tradition, or purity, but on where they happened to be sitting and who happened to be near them, and in the end the disputes and conflicting memories may count for more than the evidence preserved on tape and film—some of which must also be taken with a grain of salt, since film clips were edited to heighten the drama of the moment, splicing in the clamorous crowd noise from the beginning or end of Dylan’s set to augment the relatively low-key response captured by the stage microphones after that first song. For people standing near the stage, the biggest problem was the sound—Bill Hanley, who designed and supervised the Newport system, explains that the stage was raked, slanting toward the audience and driving the roar of the instrument amplifiers directly into the faces of the people up front, while Dylan’s voice was only coming over the field PA speakers, off to the sides. As a result, the privileged listeners at the musicians’ feet and backstage got the full blare of the instruments, and many recall Dylan’s singing as virtually inaudible. Out in the crowd the sound was better—Hanley was a pioneer of outdoor audio and says the system was capable of handling far louder bands than Dylan’s—but it still varied somewhat depending on how close one was sitting and was much louder than most listeners were used to, nor were many people in those days familiar with the intentional distortion of overdriven guitar amps. Some were thrilled, some panicked, all were startled. “It was very emotional,” recalls Peter Bartis, now a seasoned folklorist, but then a fifteen-year-old who had lied to his parents and hitchhiked to Newport for the day. “Some people were cheering, some were booing. Some were crying, they were really freaked out. I kind of liked it, but it was confusing.” What survives on tape and film is a concentrated distillation—the only microphones were onstage, the cameras were trained on Dylan—but still gives a powerful sense of the chaos and excitement”

Thanks Susan. Very interesting. Interesting how the consequence of Dylan’s request is putting Suze even more in the spotlight…

I managed Bob for several months shortly after he came to NYC, and we were friends for several years; I managed other folk singers and was part of that Greenwich Village folk music world throughout the '60s, and was at Newport in 1965. I wrote about some of it in my book, "My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me," published last year. Suze and I were close friends from the time she met Bob until she died. She was totally unlike the wimpy person portrayed in the movie. Nor was there a romantic triangle among Bob, Suze and Joan. While movie producers often create arcs to move their products along, I believe revising someone's personality and changing their life to suit your commercial purposes is a more-than-objectionable thing to do.

I talk about that and the movie's erasure of Dave Van Ronk, a folk singer friend of and influence on Bob in the early-to-mid-60s, whom I managed (and also was married to and remained a lifelong friend of) in a podcast: https://hudsonriverradio.com/being-frank.html?fbclid=IwY2xjawHuCs9leHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHSciSqQwVu8wdCelEzvz0Rm5fNylQjczUmDkSTQIOcqKzPu9hbaxrUtCkQ_aem_EKn8vU2HopU-4Jykb14dIg