All of Us Are Real: An Adoption Memoir

My daughter Cassie will be 25 this Monday. I wrote this when she was 10.

“So you’re not Cassie’s real mother, then?”

The woman’s face was innocent and open with curiosity. My then four-year-old daughter was standing beside us, impatiently waiting for the story-telling hour for toddlers to begin. I automatically shot a glance at her, wondering if she had heard. But her attention was on the Thomas the Tank Engine table, around which several little boys were clustered, arguing over who would get to be Thomas. The woman asking the question was the manager of the toddler reading program at our neighborhood “progressive” bookstore, the person parents go to for instruction and guidance when they are picking out books for their children.

Four years later, my blood already simmering from having read reviews of the book, I open Rebecca Walker’s Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence. I skim for the offending passages, and there they are, even worse than the reviews had portrayed them: “It’s not the same. I don’t care how close you are to your adopted son or beloved stepdaughter, the love you have for your nonbiological child isn’t the same as the love you have for your own flesh and blood” (69).

Walker knows this after a “lifetime,” of—what—thirty-five years? But Walker’s special brand of arrogance aside, she is hardly alone. We are living in “adoption nation,” as journalist and adoptive father Adam Pertman has named it: six of every ten Americans have either adopted a child, been adopted themselves, placed a child for adoption or have an adopted family member or close friend who is adopted (Pertman 7). Yet the belief that genetic connection is the glue that binds a family continues.

Walker goes on: “I find myself nodding,” she writes, “as I read a study that finds children living with a stepmother receive a good deal less food, health care, and education than they would if they lived with their biological mother” (73). I know about these studies. I subscribe to a listserv called “Evolutionary Psychology.” I’ve spent many an early morning—my email time—fuming over the latest theory about genetic investments in biological offspring and “natural” preferences for those who carry our DNA.

It’s not surprising, given the continuing biocentrism of our culture, that the fears and hopes of many adoptive parents, too, live in the shadow of the biological norm and all the cultural mythology attached to it. We long for the irrefutable, unbreakable bond that was not given to us “naturally,” and invent myths of quasi-biological ordainment of our own parenthood. Rosie O’Donnell, for example, on the Barbara Walters’ television special “Born in My Heart,” describes how she tells each of her three children how they came to be adopted: “You grew in another [lady’s] tummy, and God looked inside the tummy and saw there was a mix-up. God knew that you were my baby so he told the lady and she listened to God and she made sure that you came to me, your right family.”

Rosie “means well,” of course. And it’s not as though I haven’t also experienced the feeling that on some cosmic tablet, my name was etched beside my daughter’s, but I also know that such feelings are just that—feelings. In elevating them to the level of divine justification, her adoption becomes the mirror image of the bookstore lady’s designation of me as “not Cassie’s real mother.” For Rosie, it’s the birthmother’s parentage that isn’t “real,” but rather, a “mix-up,” a mistake. The “other lady’s” tummy was the wrong one.

Rosie’s story seems easy to dismiss as uninformed and unenlightened because it so blatantly evaporates the reality of her children’s biological origins. As an adoptive parent, however, Rosie has a lot of company in thinking that unless one belittles or erases the genetic connection, one cannot ever be secure or “real” oneself as a parent. “I’d be suicidal,” Connie Chung declared emphatically in her interview with Walters, if her son ever wanted to search for his birth parents (“Born”). A bit hyperbolic, perhaps. But the fear itself is not unusual. When my adoptive parent’s group heard that my daughter’s birth family had just been in town for a visit, they looked at me as though I were Mother Teresa—or simply nuts. “Lord love you,” one of them said, “but I just don’t see how you do it.”

Actually, I’m not sure that I could have done it any other way.

My husband and I met Cassie’s birthmother Amy and her family three months before Cassie was born. I returned and stayed in Abilene, Texas for three weeks before the birth. I was with Amy, her mom ViSue, and her sister Nikky for all but the actual delivery. My husband, having been alerted the night before, flew in and arrived twenty minutes before the birth. Pictures taken during the week that followed, while we waited in Abilene for various legal procedures, show three loopylooking adults, one surly teenage boy, and two beaming teenage sisters holding a tiny infant, all of us squashed together like nesting animals on the hideous but huge couch in our furnished rental unit. Amy, ViSue, and I gave Cassie her first bath. Our ages were 15 (Amy), 36 (ViSue), and 52 (me). In the ten years that have passed since, we have exchanged many photos, videos, gifts, phone calls, and half a dozen visits. Amy has married and given birth to two children, whom we all regard—Cassie most proudly and possessively—as Cassie’s brother and sister.

When I first spoke to our adoption counselor, I knew nothing about open adoption. When I found out that adoptions could be arranged in this way, it immediately appealed to me, not only for well-thought out reasons, but also for emotional ones. Secrets and lies were the modus operandi of my parents—from fairly “small ones” (birthday parties that turned out to be tonsillectomies) to whoppers. Like this one: my mother was originally married to my father’s first wife’s brother. (Yes, she was married to the brother, and my father to the sister. And if you find it a bit incestuous now, you can imagine how it was received by their working-class Jewish families in 1938.) They fell in love—my father and mother, that is—and my mother became pregnant with my older sister. It was a great scandal in Flatbush. But for some reason never fully clear to me, neither the brother nor sister would agree to a divorce. So my father and mother were forced to flee Brooklyn in disgrace and re-settle in Newark, New Jersey, where they lived together “in sin” and my mother gave birth to my sister “out of wedlock.” When they were finally, officially divorced from the brother and sister, they adopted my sister, their actual birth child.

I found all this out during my first year at college after a thinly veiled allusion, in a letter to my parents, to the loss of my virginity, which had taken place on my seventeenth birthday in my dorm room. I guess they felt that at that point I was old enough to know—or perhaps experienced enough to be warned. (My older sister had found out when her second-grade teacher asked why her name was listed as “Wilensky” rather than “Klein.” She brought the question home, and was told The Story and shown the adoption papers.) I grew up with a bad case of what I came to call, when I became a philosophy major, “epistemological insecurity”—and along with it, a fierce and sometimes annoying dedication to ferreting out lies and silences. Lucky for me that western culture was full of them, and I could make a career of it. Also lucky for me, when I came to adopt I found out about open adoption.

I was delighted to find out that it was also the best way for us to get a baby at our advanced ages. At fifty-nine and fifty-two respectively, my husband and I were not exactly ideal candidates by most agency or birth parent standards. But our willingness to participate in an open adoption, our counselor assured us, would compensate. “THIS WILL BE YOUR LAST MOTHER’S DAY WITHOUT A CHILD,” she declared with absolute confidence.

Friends and relatives were skeptical and anxious. Weren’t we afraid that Amy would bond with Cassie and keep her? Didn’t we worry that Cassie would someday want to be with them rather than us? How could we bear to share her with them? At the beginning, all I could do to reassure friends and family was to quote the literature on open adoption, which I turned to over and over in my own moments of doubt, which were many. I told them about the huge benefits to the child. It isn’t co-parenting, I assured them. And isn’t it better for Cassie to know her birth-family than to create an idealized picture to fantasize about when she turns fourteen and starts to hate me?

My own greatest fears at the beginning were about my age. En route to Abilene, I nearly fainted in Wal-Mart, then broke down in tears, anticipating what a fifteen-year-old birth mom and her thirty-six-year-old beautician mother would think about the fifty-two-year-old face that looked so much younger in our glossy brochure. Those of you who have gone through the process know that it is one of the most cringe-inducing aspects of the sales pitch that prospective adoptive parents are encouraged to construct: “We are both nuts about animals…”; “Our friends and family are the center of our lives….”; “Our house is surrounded by meadows and trees…”; “A great thing about our jobs is their flexible schedules,” and so on. Ours didn’t mention that my husband already got into movies at senior rates, and that alphahydroxies cluttered our bathroom shelves.

For our planned meeting with the birth family, I pouffed my hair to a largesse beyond high school and applied my make-up with Joan Collins on Dynasty in mind. But ViSue, at thirty-six, looked barely younger than me. It was a shocking recognition of how privileged my life had been, a concrete encounter with the class-bias of beauty, and of the entire adoption process itself. Reality check number one.

Everyone was strained and frightened. Amy, buttoned up to her chin in a demure blouse, seemed to be concentrating all her energies on simply enduring, saying “thank you” when required, and producing an occasional wan smile. Was this the same girl who had told me on the phone that open adoption sounded wonderful, that she loved talking to me, that she wanted me with her during her delivery? Reality check number two: Amy was in fact very depressed, and now that the plan was actually proceeding, couldn’t look at me without getting even more depressed. She was also angry. But I didn’t know that at the time. Like most adoptive parents, I was fumbling along, looking for rules that didn’t exist for situations that I was completely unprepared for.

Amy wouldn’t talk to me. But I assumed, incorrectly, that it was just shyness— so I relied on ViSue and the doctor who had passed our brochure on to them to lead the way. They reassured me that appearances to the contrary, Amy wanted the adoption, that she liked us very much, and that she was just nervous about meeting us.

It was what I wanted to believe, so I did. When ViSue invited us to accompany them to Amy’s next sonogram and Dr. Bass handed that precious photo to me, I took it, weeping with joy. I took my cue not only from Dr. Bass but also from cultural imagery. After all, hadn’t I seen moments just like this in Immediate Family and other adoption movies? In the pop opera version of the open adoption, birthmothers take their infants back (invariably to return them after a period of confronting their own inadequacy as mothers), but until the postpartum turnaround, it’s just one big happy family: the adoptive mom wiping the sweat from the birth mom’s brow in delivery, the adoptive dad cutting the cord.

Reality check number three: in real life, the dramatic arc of an open adoption is usually the reverse. Ambivalence and wariness comes before clarity and intimacy, and it’s the intimacy—hard-won, not movie-magical—that has the power to resolve the ambivalence. That intimacy can’t develop, however, without an acknowledgement of the realities of love and loss that are inevitable in any adoption, no matter how young the birthmother or how upbeat those around her.

But I had to learn this. I was thus startled and horrified when Amy, who had been lying silently throughout the sonogram, jumped up from the table, dressed hurriedly, and ran angrily out of the office to the parking lot and into her mother’s car, slamming the door behind her, refusing to talk to any of us. I ran after her and begged her to open the door, but she remained stony and stormy, her mouth set in an expression that I have since come to know quite well when our daughter gets in an angry mood. The next day, I took her to the mall, bought her chic-fil-a, and tried to break the ice. Not successful. My husband and I left Texas shortly thereafter, sad and anxious, knowing that there was a good possibility the whole thing had fallen through.

I had many sleepless nights after that, and not only because I was afraid Amy would change her mind. One morning, in fact, sobbing to my husband that I couldn’t take Amy’s baby away from her, I almost changed my mind myself. In retrospect, I was horrified at my behavior at the doctor’s office. I had stood there, conducting transactions over the prone, semi-undressed body of a silent, sad, and withdrawn young woman, and let myself be lost in the illusion that it was all okay because she was so young. Reality check number four. Amy may only have been fifteen, but that sonogram, as it turned out, meant a great deal to her: it was for her a concrete symbol and reminder of the fact that although she was going to relinquish Cassie to me after her birth, during those nine months she was still her mother. She wanted us all to acknowledge that. Instead, we were treating her like a pregnant child.

It was only much later that I found out how much Amy needed us to honor the reality of her motherhood. Desire makes one stupid, I guess, and selfish. At this stage, I only knew—from ViSue—that Amy had wanted that sonogram, and was furious with us all for giving it to me instead. I immediately sent it back to her, express mail, with a note that was both heartfelt and self-serving at the same time:

Dear Amy:

I’m sending this back to you. I never felt right about the fact that Dr. Bass gave it to me without asking you. I thought it was something that you and he had decided together, and when I realized that wasn’t the case, it bothered me very much.

I’m glad you talked to Ellen and had the chance to express your feelings. She says you don’t want me to come down beforehand and be there at the delivery. That’s fine. I must have misunderstood; the main reason I planned to do that was because I thought you (and ViSue) wanted it. I guess the lines of communication haven’t been that great between us! It sounds as though you are much more ambivalent about the adoption than I realized. I won’t lie to you—hearing that has depressed me very much. But the important thing is that you and your mom figure out what you want. I’ve been acting as I have based on what I thought you wanted. But I can see now that what were meant to be reassurances of our commitment to you, your family, and a truly open adoption probably felt like over-bearing intrusions to you.

Whatever you decide to do, please don’t think of me as your enemy. If I (or Edward) have done anything that has hurt or offended you, it’s been out of lack of knowledge about what you wanted, and awkwardness in a situation that is completely new to us, too. Like you, we’ve been counting on the “professionals” to show the way. So when Dr. Bass gave me that sonogram, I didn’t let my own instincts guide me enough. I now regret that very much.

Edward sends his best. He’s also upset, but he wants the right thing to happen for you. Without that, it can’t be right for us.

Susan.

Did I mean it? Yes and no. The process had tangled up my feelings. One part of me was trying to bring Amy back into a trusting relationship with me so the adoption would proceed. But I had gotten to know Amy and her family well enough to realize that it would be far from a disaster for the baby if they decided to raise her. I was growing more and more emotionally attached to the as-yet-unborn baby. I wanted her. I wanted what was best for her. I wanted Amy to be okay. And I wanted to be happy myself after so many years of sadness. I was so full of conflicting emotions that I sometimes felt I didn’t know who I was anymore.

Ultimately, Amy and I developed a very different relationship with each other. This came in part as a the result of counseling, which provided a safe, private place for me to give her the acknowledgement she needed and to establish a separate friendship with her apart from her mom, whom she hated at the time for not being willing to raise the baby with her. Over time, after I returned to Abilene to wait with the family for Cassie’s birth, Amy came to confide in me about quite intimate matters.

The breakthrough for both of us came the day we bought matching baby books together, then sat on the floor as she finally told me the whole story of her brief relationship with Cassie’s birth father. “Oh my God, he’s gorgeous!” I exclaimed when Amy handed me the crumpled photo. “Let’s forget the baby, I’ll take him home instead!” We broke up laughing. The photo was a blurry black-and-white, but Jerome’s sexual charisma defied the poor technology.2 Broad shoulders, coffee-with-cream-colored skin, sharply defined cheekbones—when I looked at his picture, then back at doe-eyed, even-featured Amy, it suddenly dawned on me that this baby was going to be stunningly beautiful. One isn’t supposed to care about such things, but it was impossible not to.

Throughout our developing relationship, I never stopped worrying that Amy might change her mind, and I knew I would be heartbroken if she did. But I also recognized that heartbreak was inevitable here, for one of us and perhaps for both of us. It’s normative in adoption; it can’t be avoided. Reality check number five. I thought about adoption stories and movies in which the birthmother changing her mind is presented as a betrayal of the emotional investment of the adoptive parents— and the way their grief, the pain of losing the dreamed-of child, is so highly honored. Everything then gets better, and the happy ending is achieved, when the birthmother brings the baby back. I knew that I could never see it that way. Yes, I would grieve—and perhaps even rage at the universe. But I would not feel betrayed by Amy. I knew that if she changed her mind it would be the result of an unanswerable cry of protest, coming from her heart, a heart I had come to cherish and feel protective of.

Remarkably, as this was happening to me, the same thing was happening to Amy and ViSue. One day quite near the time of Amy’s term, ViSue confided in me that as they rode to the doctor’s a few days before, Amy had plaintively asked her, “Mom, can’t we keep her?” When I heard this, all the clichés immediately came true: my heart nearly stopped, a cold chill went through me, I began to tremble uncontrollably—and I quickly placed a call to my doctor back home, requesting extra Xanax. Adequately medicated, I tried to not interfere and let it play itself out, however that might be, but I couldn’t. A few mornings later, in a state, I visited ViSue to get an update. Seeing how anxious I was, she put her arms around me and then took my face in her hands. “You poor honey-bun,” she said, “don’t worry. We’d never take your Cassie away from you!”

My Cassie? I hugged ViSue in relief, but it took me a long time to believe in that privilege myself. Amy did decide to proceed with the adoption, but that didn’t make the reality of her bond with Cassie any less real to me. Unlike many adoptive mothers, who speak passionately about “falling in love at first sight” and immediately feeling that this child was meant to be theirs, I was caught in the existential strangeness of it. After Cassie’s birth, I couldn’t fully take in the fact that where there had been no baby, now there was one. She was mine? In what sense mine? There, on the bed, lay Amy, her birthmother, exhausted and trembling from the delivery, fifteen years old, stalwart but grieving for the little girl she had to give up. And then there was me, fifty-two years old, with all my book-knowledge and a bunch of paperwork in a file. Who was the mother here? Me? Not yet.

For a long time, I was haunted by Amy’s loss—by the violence life had done to her in not giving her the resources to raise her baby— resources, both emotional and material, that I had in such shameful abundance. At the same time, Amy and ViSue had advantages that I envied desperately. A three-time mom, ViSue seemed to know exactly how to hold Cassie, feed her, bathe her. My education in baby-care was largely from books; we fought about the safety of talcum powder and Q-tips as though our maternal authority were on the line. Later, during their first visit to Lexington, when Cassie was just four months old, at Amy’s request we had her ears pierced. Watching Amy soothe her crying, rocking her body as naturally as though it were still connected to her own, I felt like an incompetent and a fraud. Six months later, all that had changed. On her second visit, I caught Amy gazing at Cassie and me with tears in her eyes. “Are you feeling sad?” I asked. “No,” she replied, “I just love the way you talk to her. I wish I had been talked to like that.”

As for Cassie’s birth father, he existed, as so many birth fathers do, at the margins of the entire drama. In Jerome’s case, it was by choice. Married to someone else who was herself pregnant, he relinquished his parental rights more than willingly, once he understood that acknowledging paternity—which he had to do, of course, in order to relinquish his rights—wouldn’t make him responsible for the child. Until he understood that idea, however, he continually evaded phone calls and missed appointments with the social worker, and we all began to wonder what was going on. Edward and I were nervous; might he actually contest the adoption? The social worker was sure he wouldn’t, but Amy’s mom was furious. Had he tried to contest the adoption, her plan was to have our lawyer remind him that legally, what he did with Amy was statutory rape.

Legally, of course, it was statutory rape. Still, it was very hard for us to see him the way Amy’s mother did, as a cold-blooded sexual predator. Twenty-one years old, Jerome was not exactly Humbert Humbert. Like Amy, he had few options in life. Like Amy, he was stifled and stupefied by the dead-end world they lived in. Like Amy, he had a spark that was never allowed to flame except in sports and in the experience of desire and sexual power. Beautiful, depressed, willful, they both got caught in that snare. Sex was available, affirming, and, unlike swank apartments and snazzy jobs, a piece of the American dream that they could actually grasp, hold in their arms.

I spent many hours worrying about Amy and what the experience of giving up a child was doing to her. With Jerome, I only worried about getting his signature on the line. He made himself easy to dismiss, because in so many ways, he fit the stereotypical absentee birth father profile: he didn’t take responsibility, was eager to absolve himself of it, and had no interest in further contact with the child. But for all his seeming indifference, I knew there was another story there.

We met him once, after Cassie was born. Edward spent a half hour or so talking to him, mostly about Jerome’s successes as a high-school athlete, and was struck by his sweetness and charm. Then he went in to see Amy and the baby. We weren’t there for most of that meeting, but when we came in at the end Cassie was cradled in his arms, and his eyes were wet with tears.

When Jerome got up to leave, I told him that I would like to stay in touch, in whatever way he was comfortable with. In fact, I wanted this passionately, for Cassie’s sake. But he had a wife and another child, and I didn’t feel I had the right to intrude or press too hard for contact. He said he’d like to keep in touch, too, and gave me his cell phone number. But he looked restless, and I suddenly felt like a teenage girl at the end of a fabulous date, hoping and yet knowing there wouldn’t be another.

The fleeting intuition turned out to be reliable. When I tried to call Jerome on his cell phone three months later, wanting an address to send pictures to, he never picked up, no matter what time of day or night. There was no way to leave a message. So I looked up his last name in the Abilene directory, trying number after number. Finally, one day, his grandmother answered. She knew there was an adopted baby somewhere and seemed delighted to find out more. We had a funny and warm conversation, and I became hopeful that some kind of connection might be established. “Lord knows that boy needs to learn to keep his pants zipped,” she said at one point, and we sighed and clucked together, affectionately, knowingly, like family.

I sent the pictures, but she never replied, and when I tried to reach her again, I met with a dead-end. Right now, I don’t even have a picture of Jerome. Amy’s crumpled photo was lost in a fire, and she claims she has no idea where he is. I look at Cassie, whose hair, skin color, facial features, and strong, sturdy body are so much like his, and stew about what to do. I want my daughter to know her birth father, her siblings on his side, and whatever extended family there is. He, however, doesn’t appear to want this. Cassie doesn’t seem to care yet, but I know that will probably change. What do I do? I don’t know. Reality check number six. Or is it seven? Or is it seven hundred?

A few weeks ago, at a meeting of a site-based decision board at Cassie’s school, I brought up the subject of the importance of the language that we use in talking about adoption. The principal pooh-poohed over my concerns about the word “real.” “Hell,” she said, “I’m adopted, and I got that stuff all the time. I grew up just fine.” Perhaps, as one trained in philosophy, I do attach too much importance to words like “real.” The bookstore lady may have thought she was just asking about the biological status of my relationship with Cassie, and Cassie’s principal, tough broad that she prides herself on being, may believe that it’s no big deal. But there was another adoptive mom at the meeting, and when the principal dismissed my concerns, her eyes sought mine like magnets. We both know what it feels like to be told we are not “real” mothers. I feel equally angry, however, when Rosie O’Donnell suggests that Cassie’s nine months in Amy’s body was God’s “mix-up,” a cosmic mistake.

I’m not a Platonist. I don’t believe in Timeless Truth. The definition of reality that I like the best is science fiction writer Philip K. Dick’s: “Reality,” he writes, “is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” It’s particularly apt in the context of adoption. For whether they are living or dead, down the street or across the globe, known or unknown, hated or loved, every adoptive child has at least three parents. You can try to forget it, close your eyes and ears and imagination to it, tell myths about it, tremble before it, erect barriers to it, exclaim, as Connie Chung does, that you will be suicidal if it is let into your life, but it will be in your life. Attempt to deny it, as our adoption practices did for decades and as some adoptive parents still do today, and you will merely create another version of it, nurtured by imagination rather than knowledge. From Emily Hipchen’s memoir, Coming Apart Together: Fragments from an Adoption:

I can remember being a child and dreaming my imagined mother alive. In my most difficult moments, she was there, really there, absolutely tangible, warm and dark, large and reassuring. I believed, in these moments when I could not get what I wanted, when I was angry or sad or confused, I really believed she was a better mother than mine, not so short-tempered, not so difficult to understand, not so other-than-me. I knew, if I could just find her and keep her, she would love me, she would smooth the way for me, she would give it all to me and make my life easy because she would know me, not as one comes to know a stranger over time, not as my parents knew me, but as one knows one’s own fingers or eyes. She would welcome me, I thought then, as a part of her body she’d been missing all those years, as an integral part of herself she would catch up again, as one does one’s own breath after falling hard. This was fantasy. (40–41)

Fantasies of an ideal parent other than the one you are living with are natural, of course, and not limited to adopted children. I mention fantasy not to suggest that something is wrong when a child fantasizes, but to emphasize that it is as potent a “reality” as any other. Connie Chung may be able to stop her child from searching (if he wants to search, and not everyone, of course, does), but she cannot stop him from imagining, desiring, wishing. She’s going to have to deal with those other parents one way or another.

It may not be as traumatic as she imagines. When Cassie is angry with us, she often threatens to run away to Texas. (This is how she imagines Texas: everyone has a horse, a guitar, and a great big hat.) Once, after Amy’s little boy Brennon had been born, Cassie mused wistfully, “I wish that I had been born second, not first.” “How come?” I asked. “I don’t know . . ..” she replied. “Is it because then Amy could have kept you?” I asked. “Yes!!!” she replied, with enthusiasm and relief. “And that way I’d get to live in Texas and could wear sleeveless shirts all year round!”

Let me conclude by saying that not for a moment do I want to be seen as proselytizing for the kind of open adoption Edward and I have. It’s not for everyone.3 Having stumbled into it, I had no idea what hard emotional work would be involved. But then, adoption is hard work no matter how you do it. Parenthood is hard work no matter how you do it.

Amy, now married, has given Cassie the brother and sister that we can’t provide. Cassie is extremely proprietary about them and loves saying the words “brother” and “sister.” At this point in her life, at age ten and one of the few children in her class with ancient parents and no at-home siblings, they are much more important to her than Amy or ViSue. Rather than making her feel “different” by virtue of highlighting her adoptive status, her birth family makes her feel more “normal,” more like the other kids in her class, with their grandparents, brothers, sisters, and other members of an extended family.

I had no idea just how comfortable she was, however, until Amy and ViSue brought her siblings—Brennon, then three, and Hayleigh, then one—for their first visit. We all had lunch in the cafeteria together, and then, on return to the classroom, Cassie asked her teacher if she could introduce them all to her class. She led them to the front of the room, and pointed to each one. “This is my brother Brennon, my sister Hayleigh, my grandma ViSue, and my birthmother Amy.” She was beaming. They were beaming. Standing in back of the room, the clichéd lump in my throat, I was beaming. Cassie’s teacher was beaming. It was one moment in an ongoing story, not a fairytale ending. But it felt wonderful.1

Every adoption is different. This was my experience. If you are so inclined, please do share your own!

For my reflections on adoption post-Dobbs, see

The Dobbs Decision: An Adoptive Mother’s Perspective

Megan She was fifteen years old. It was just a hook-up at the local mall with the twenty- one-year-old ex-football star all the girls had a crush on. He left Megan with a venereal disease that took her to the doctor, where she found out she was preg- nant. It was too late for an abortion, and Megan was still living with her mom, who was already strugglin…

Works Cited

“Born in My Heart: A Love Story.” Barbara Walters’ ABC Special. ABC Barbara Walters, Rosie O’Donnell, Connie Chung. 20 Apr. 2001.

Hipchen, Emily. Coming Apart Together: Fragments from an Adoption. Teaneck, NJ: Literate Chigger, 2005.

Pertman, Adam. Adoption Nation: How the Adoption Reform Revolution is Transforming America. New York: Basic, 2000.

Walker, Rebecca. Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood after a Lifetime of Ambivalence. New York: Penguin, 2007.

The earlier published version of this piece includes a discussion of media depictions of adoptions. Most of the movies I discuss would be unfamiliar to readers today and including that section would have made the piece way too long, so I left it out. If you’re interested: https://bordocrossings.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Will-the-Real-Parents.pdf.

very captivated by this essay. appreciate your nuance and honesty! family is complicated no matter the set up

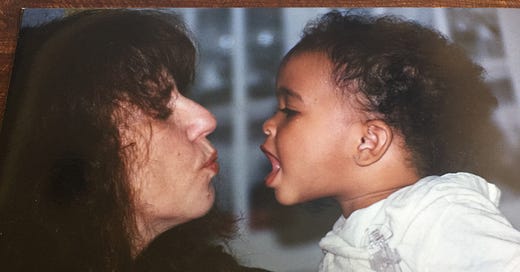

Wonderful. The photo too. I am glad for your family’s hard-won happiness.