“Anne of the Thousand Days”: Why We Cheer for Genevieve Bujold’s Anne Boleyn

It was an honor to interview Genevieve Bujold for my book on Anne Boleyn. The following includes exclusive material from that interview. If you know a Boleyn fan, please do share!

Fiction and Truth

We think of “the truth of history” as demanding a strict adherence to fact. But there are historical truths that need fiction to serve them.

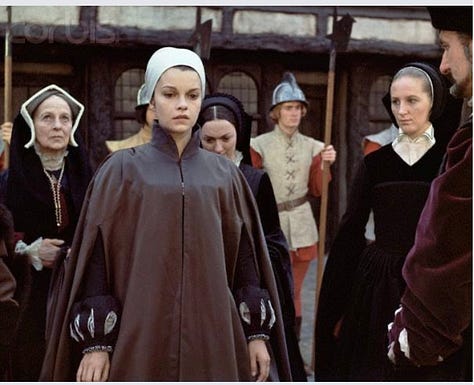

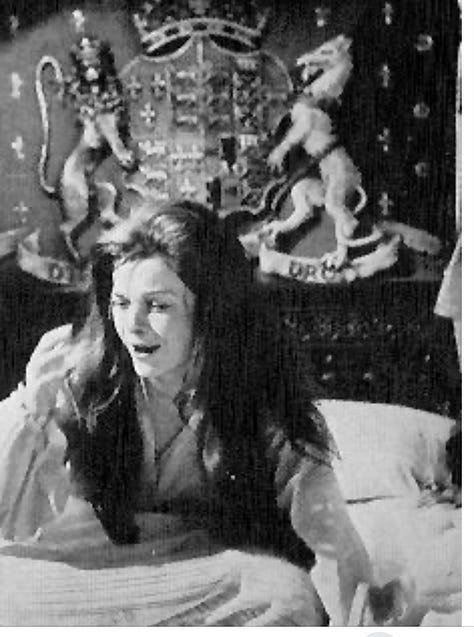

There is a scene in the 1969 film version of Anne of the Thousand Days that has audiences cheering to this day. Henry VIII (Richard Burton) visits Anne Boleyn (Geneviève Bujold) as she awaits execution in the Tower of London and reflects on the “thousand days” of her marriage to the king. He has come to offer a bargain. If Anne will declare their marriage unlawful and their daughter Elizabeth illegitimate, freeing him to marry Jane Seymour, he will spare Anne’s life. But Anne is having none of it. Her hair disheveled, eyes burning a path straight to his masculine pride, she rejects the offer and spits out a lie: “It is true. I was unfaithful to you with all of them. With half your court. With soldiers of your guard, with grooms, with stable hands. Look for the rest of your life at every man that ever knew me and wonder if I didn’t find him a better man than you!” Rattled and enraged, Henry shouts, “You whore!” Anne has an even sharper arrow in her quiver:

“But Elizabeth is yours. Watch her as she grows; she’s yours. She’s a Tudor! Get yourself a son off of that sweet, pale girl if you can—and hope that he will live! But Elizabeth shall reign after you! Yes, Elizabeth—child of Anne the Whore and Henry the Blood-Stained Lecher—shall be Queen! And remember this: Elizabeth shall be a greater queen than any king of yours! She shall rule a greater England than you could ever have built! Yes—MY Elizabeth SHALL BE QUEEN! And my blood will have been well spent!”

The scene is without historical foundation. Henry never visited Anne in the tower, and Anne never delivered her speech; indeed, at that point, Anne would have known that the chances of Elizabeth becoming queen were slim. Two days before her execution, her marriage to Henry was declared void, and Elizabeth would soon be bastardized. In the movie (and before that, the 1948 Maxwell Anderson play on which it was based), she is given a choice that the real Anne never had.

Did the fact that the tower scene was invention matter to viewers? Not a bit. While critics at the time were not particularly enthusiastic (Vincent Canby was typical in praising Bujold but disparaging the movie as “unbearably classy” and “conventionally reverential”), not one complained of the historical inaccuracies. Even today, among audiences who have seen enough alternative versions of Anne’s final days to wonder about the authenticity of any of them, the general consensus about the tower scene seems to be that if it didn’t happen that way, it should have.

Anne of the Thousand Days is not the only Tudor drama to escape the scrutiny of fact checkers. Sixties’ critics were so enchanted with the 1966 film A Man for All Seasons’ witty, anti-establishment dropout Thomas More (Paul Scofield) that they were unconcerned with its whitewashing of More’s obsessive, brutal heretic hunting. And while the TV series “The Tudors” got slammed for its liberties with history, 1the late Hillary Mantel’s quirky yet magisterial portrait of Henry’s minister Thomas Cromwell has gotten away with many serious omissions and inventions of fact not just because of Mantel’s artistry as a writer, but because of the way she captures the precarious yet oddly cozy world of the Tudor court—a “truth” that mere facts can’t convey.

Some depictions—for example, Alexander Korda’s film The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933)—get away with nonsense simply because they were created long enough ago that they are viewed as cultural artifacts. Others give offense because they are considered “pop” rather than “literary,” and vice versa. Mantel’s trilogy, on the other hand, is such a dense, detailed, challenging work that I have wonder whether critics were afraid to question its fidelity to history because, like students in a high-theory college course, they were afraid of displaying their ignorance.

What is seen as objectionable often depends on what you care about. The historian Retha Warnicke “shuddered” at Micheal Hirst’s (“The Tudors”) merging of Henry’s two sisters into one character. I, on the other hand, was most offended when, in the third episode, Francis I’s sister, Marguerite de Navarre—author, intellectual light of the French court, and a deep believer in platonic love between men and women—appears as a visitor to the English court, bosom spilling out of her dress, casting hot glances across the dining hall at Henry as both bite into their roasted thighs and wings, Tom Jones fashion. Later that night, two guards stoically keep watch while Henry and Marguerite grunt and moan behind his bedroom door. Most viewers would not have realized that a distinguished historical figure—often called “the mother of the Renaissance"—was being turned into a trollop for the sake of ratings. But for those who are devoted to the history of women, it seemed not merely gratuitous but nasty.

Television and movies, because they carry the illusion of verisimilitude, are more likely to be criticized for historical inaccuracy than novels, no matter how often their creators insist that they are not meant to be entirely factual. If, however, they comport themselves with enough dignity—like the 1970 BBC production of The Six Wives of Henry VIII—they are off the hook. The inventions of more recent productions are apt to be not only sexually sleazier but more epistemologically seductive. If the (often digitally-enhanced) reality is vivid and convincing enough it carries authority. So, thanks to the “realistic” trappings of The Other Boleyn Girl, my students came to my Anne Boleyn course sure that Anne Boleyn “stole” Henry from her virtuous sister, Mary (in fact, the Mary/Henry affair was over by the time Anne entered the picture), was raped by Henry, proposed sex with her brother George in order to conceive a child (a charge to which only one historian that I know of gives any credence), and Oh, and another trifle noted by the critic Jonathan Jones—the movie “manages to virtually edit out a rather large historical fact: the Reformation.”

Mantel told me in an e-mail interview: “You have to think what you owe to history. But you also have to think what you owe to the novel form. Your readers expect a story. And they don’t want it to be two-dimensional, barely dramatized.”And in the case of Tudor history, there are plenty of gaps that beg to be filled in by the creative imagination if there is to be any coherent narrative at all. One of the biggest is Anne Boleyn herself. Even before her execution, Henry set about erasing all evidence of her life—emblems, portraits, and (apparently) letters—a purge that has allowed polarized camps to define and redefine her over the centuries. For supporters of the queen she supplanted, Katherine of Aragon, she was a coldhearted murderess. For Roman Catholic propagandists, a six-fingered, jaundiced-looking erotomaniac. For many Elizabethans, she was the unsung heroine of the Protestant Reformation. For the Romantics, particularly in painting, she was the hapless victim of a king’s tyranny.

In her interview with me, Mantel astutely observed that “all historical fiction is really contemporary fiction; you write out of your own time.” I agree. Her morally ambiguous, watchful Cromwell is a man for our cynical season, in which the border between truth and fact is so “permeable.” But there seems to be something timeless about Genevieve Bujold’s Anne Boleyn. That totally invented tower scene still carries truths about Anne’s personality—what we know about it, that is—that continue to make her many viewers’ favorite Anne. Perhaps, too, still today, perhaps especially today, we just want so, so much for tyrannical men to be told off. And Bujold’s Anne does that for us.

“Anne of the Thousand Days”: From Stage to Screen

Most movies of the late 1960s have not worn exceptionally well, particularly with today’s generation of viewers, for whom many of the lifestyle protests of the time seem dated and silly. My students snoozed through Easy Rider. With Anne of the Thousand Days, the passing years and changing culture have had the opposite effect; my students adored it, especially loving an Anne who seems to become “truer” as the generations have become less patient with passive heroines and perhaps a bit tired of the man-focused femininity of many current female stars. Some of my students’ comments:

“Everything I imagine Anne really was”

“How I always picture Anne—as a strong woman not a sniveling girl”

“The gold standard of Annes”

“When I imagine Anne, it is her that I see”

“The definitive Anne Boleyn for me”

“Pitch-perfect”

“So powerful that she turned a big, tough guy like me into a whimpering fool”

“A remarkable actress. I will never forget the scene where she and Henry

go riding from Hever . . . Purely from her body language, she radiates suppressed hatred toward Henry — just by sitting on a horse! And who can forget her in the blue gown, with jewels in her hair, looking devas- tatingly beautiful and in total command of herself and the situation.”

How did Bujold come to play Anne?

That happened through a magical confluence of Maxwell Anderson’s play, the longings and insights of Hal Wallis, producer of such distinctively American hits as True Grit, Casablanca, Barefoot in the Park, and all of Elvis Presley’s movies, the culture of the 1960’s, and of course Bujold herself.

The child of immigrants from Russia and Poland, Wallis had grown up in a Chicago tenement, in an Eastern European Jewish enclave of garment workers and small shopkeepers. And from an early age, he adored all things British. As soon as he had made enough money from early hits such as Little Caesar and Yankee Doodle Dandy he began to dream of making films that would introduce British history — which he had studied, on his own, since childhood—to movie-going audiences.2

Discounting The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Wallis’s earlier forays into British history had been The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), with Bette Davis and Errol Flynn and Jean Anouilh’s Becket (1960), with Peter o’Toole as Henry II and Richard Burton as his wenching buddy Thomas Becket, who become tormented adversaries in a battle between allegiance to king and the demands of conscience. 3

Wallis had seen and admired Maxwell Anderson’s Anne of the Thousand Days when it was playing on Broadway in 1949. The play had been a surprisingly popular success, despite the fact that it is written in a combination of prose and verse, and often wanders into long, somewhat pretentious poetic monologues. The key to its popularity was the domestic drama at its center: a battle of the sexes between Henry and Anne, within which they behave more like a man and a woman than a bluebeard and a vixen in a Grand Historical Drama. And as conceived by Anderson, they were also a challenge to previous depictions of the pair.

Most audiences of the play would have been familiar with the Henry played by Charles Laughton, who in Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) bequeathed to us the enduring image of Henry devouring a chicken, tearing off a chunk, taking one bite, then chucking each piece over his shoulder as he dives for the next while burpingly lamenting the death of civility. They would have expected a buffoon; a leering bloated tyrant: “Bluff King Hal,” the jovial serial collector of wives. Instead, in Anderson’s Anne of the Thousand Days they got manly, handsome Rex Harrison (who won a Tony for the role), charming and suave, but also calculating and dangerous.

Anderson’s Anne was played by petite but feisty Joyce Redman, who brought a fiery, rebellious independence to the role. Previous depictions, both historical and fictional, had tended to veer back and forth between the familiar archetypes of scheming seductress and hapless virgin. Anderson’s Anne, in contrast, was “a high-spirited, high-minded girl who made this marriage a term of her being: and who, apparently without a drop of fear, refuses Henry’s advances and calls him out: “You are spoiled and vengeful and malicious and bloody. The poetry they praise so much is sour, and the music you write’s worse. You dance like a hobbledehoy; you make love as you eat—with a good deal of noise and no subtlety.”

Although in “real life” this attitude would probably have resulted in her head going missing much earlier in the story, in the play it inflames Henry’s desire for her, and he vows that “[i]f it breaks the world in two like an apple and flings the halves into the void, I shall make you queen.” Anderson’s Anne also has a sexual past—she confides to Percy, her first love, that she slept with men while she was in France and even before that. Anne’s enemies had claimed that too, but as proof of her wantonness. Here, it’s irrelevant to the play’s assessment of Anne’s moral character. She’s not a virgin — big deal. The king knows it and doesn’t care. Neither does Percy. She tells him about it matter-of-factly, without a hint of coyness; she’s more the modern “liberated” woman than either the trembling virgin or the temptress who endows sexuality with subversive power.

When Henry and Anne finally sleep together in the play, it is a wildly transporting experience for both of them: “I’m deep in love,” Anne declares (so deep she no longer cares about the divorce), and Henry proclaims it “a new age. Gold or some choicer metal — or no metal at all, but exaltation, darling. Wildfire in the air, wildfire in the blood!”

The irony (and existential essence and dramatic spine of the play) is that falling in love with Henry after years of hating him is the beginning of Anne’s downfall, for it finally releases him from his erotic bondage to her. “After that night,” she muses later in her room in the Tower, “I was lost.” What follows is the speech that gave the play its title.

From the day he first made me his, to the last day I made him mine, yes, let me set it down in numbers. I who can count and reckon, and have the time. of all the days I was his and did not love him — this; and this; and this many. of all the days I was his — and he had ceased to love me—this many; and this. In days—it comes to a thousand days — out of the years. Strangely, just a thousand. And of that thou- sand—one—when we were both in love. only one, when our loves met and overlapped and were both mine and his. When I no longer hated him, he began to hate me. Except for that one day. one day, out of all the years.

I’ve always loved that speech for its psychological acuity about the kind of love that is fueled by challenge and pursuit, as Henry’s desire for Anne was. Whatever her motives, Anne was not easily conquered. This may have inflamed Henry’s passion, but it also meant there was a danger to Anne in finally giving in. For what he found in his arms was a real woman rather than a fantasized ideal—and as a real woman, Anne, having been elevated in Henry’s imagination by years of longing, was bound to disappoint.

Anne and Henry’s sexual attraction for each other does not degenerate starkly or decisively, though. Even after Henry has begun to court Jane, he still can be aroused by Anne; when her fury is ignited, so is his desire for her. And furious she often is — over his betrayal, over the prospect of Elizabeth’s being made a bastard, and over Henry’s underestimating of her integrity. No fictional Anne before had ever been so proudly defiant, so insistent on her own autonomy, so utterly unintimidated by Henry. For drama critic Joseph Wood Krutch, this is what made Anderson’s Anne so “intriguing.” “In her own way she is as ruthless as Henry, no dove snatched up by an eagle, but an eagle herself. What she has is a prideful integrity incapable of a sin against herself, though quite capable of most of the other sins in the calendar.” This inability to “sin against herself ” ultimately sends her to her death, but it’s also what gives her enormous power. She will risk anything, endure anything, in order to retain her self-respect. Even at the end, condemned to death, she continues to challenge Henry, tormenting him with a lie that is also a final show of her unwillingness to “do all this gently,” as Henry would like.

“Before you go, perhaps you should hear one thing—I lied to you. I loved you, but I lied to you! I was untrue! Untrue with many!” She thus leaves Henry with an uncertainty that he will “take to the grave” (as she puts it). Did she? Didn’t she? Unknowable and elusive once again, she goes to her death knowing that her own power in the relationship has been restored. And ultimately, Henry comes to see that he has paid an enormous price, but that “nothing can ever be put back the way it was.” In the final speech of the play, Henry muses on the magnitude of what has changed for his country (“the limb that was cut from Rome won’t graft to that trunk again”) and, with Anne’s ghost hovering in the background, he begins to realize that “all other women will be shadows” and that he will seek Anne “forever down the long corri- dors of air, finding them empty, hearing only echoes.”“It would have been easier,” he now recognizes, “to forget you living than to forget you dead.”

As successful as it was, Anne of the Thousand Days was not made into a movie until twenty years later. It was deemed untouchable by movie studios in 1949, as it dealt with subjects — adultery, incest, illegitimacy, even the word “virgin” — that the Motion Picture Production Code would not permit. It wasn’t until the sixties that the code began to be killed off, bit by bit, by the “foreign invasion” of sexually franker European films and the need for American movies to offer something that television could not. In 1966, Mike Nichols’s screen adaptation of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? — a less fatal but more foul-mouthed “bad romance” than Anne of the Thousand Days—did the code in. And Anderson’s Anne was ready to be revived for a new generation.

In 1964, when Wallis first acquired the rights to the play, the New York Times announced that he was negotiating with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton to play the roles of Anne and Henry. According to Wallis, however, he never actually considered Taylor for the role, although she wanted it desperately. He recalls a lunch with Liz in 1967:

Elizabeth hung on my every word. I was surprised by her attention, as there was no part in the picture for her. Then, over an elaborate dessert she took a deep breath and said, ‘Hal, I’ve been thinking about it for weeks. I have to play Anne Boleyn!’ My fork stopped halfway to my mouth. Anne Boleyn? Elizabeth was plump and middle-aged; Anne was a slip of a girl. The fate of the picture hung in the balance. I could scarcely bring myself to look at Richard.” Burton, however, “handled it beautifully. He put his hand on hers, looked her directly in the eye, and said, ‘Sorry, luv. You’re too long in the tooth.’” Any hard feelings were handled by a huge fee for Burton ($1,250,000 plus) and cameos for Liz (as a masked dancer at a ball) as well as for Burton’s daughter Kate and Taylor’s daughter Liza.

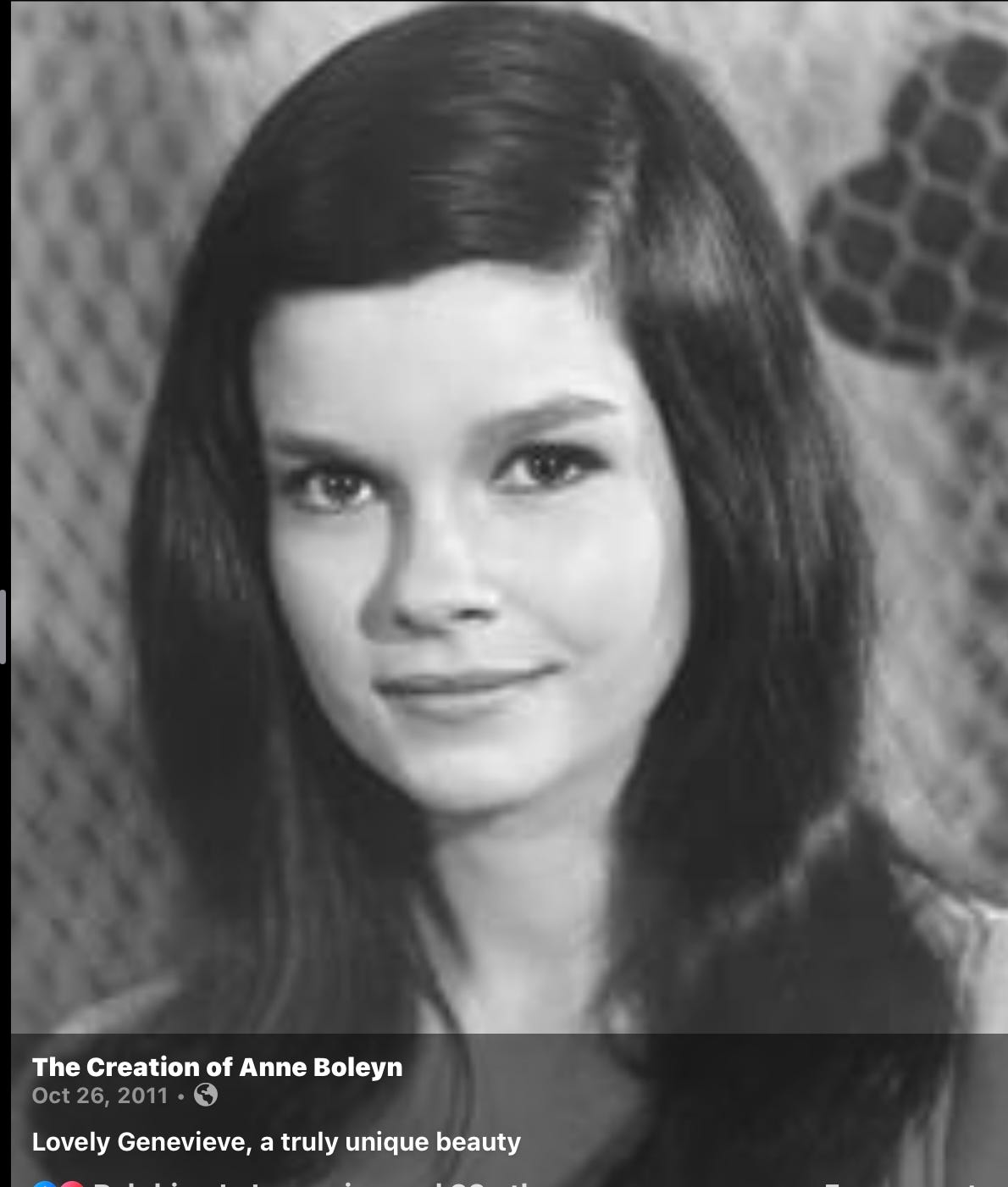

The young woman Wallis settled on for Anne, after the usual “exhaustive search,” was a virtually unknown French-Canadian actress named Geneviève Bujold, whom Wallis spotted in an independent Canadian film called Isabel (directed by Bujold’s then-husband, Paul Almond). Finding her, Wallis recalls, was a “miracle.”

The minute [Geneviève] appeared on the screen, I was riveted. I saw a tiny, seemingly fragile woman made of steel—willful, passionate, intense. She was exactly the actress I wanted to play Anne Boleyn. Even her French accent was perfect: Anne had been educated in France. I hired the girl without meeting her or testing her. [When] we met, everything about her confirmed my prediction that she was a very special personality: unique, perfect for Anne.

.

Genevieve Bujold’s Anne

Genevieve Bujold’s performance, and a few key changes in the play, were to make quite a dramatic transformation in the Maxwell Anderson original. Anderson’s play, despite its fireball Anne, was really Henry’s story. It’s Henry who has the final word, who makes the final pronouncements about history, whose torments we are left to imagine. The film, however, ends very differently. The screenplay, adapted from the play by Bridget Boland, John Hale, and Richard Sokolove, has Henry, in our last glimpse of him, listening for the signal sounding Anne’s death, then galloping off to see Jane Seymour with nary a second thought. In place of his sober, sad reflections at the end of the play, we see little Elizabeth, a sprig of flowers in her hand, toddling down the path toward greatness (actually in the gardens of Penshurst Castle) while her mother’s voice in the background predicts her daughter’s glorious future.

The voice-over is a repeat of part of an earlier speech, the one I discussed in the first section of this piece, theone that has viewers cheering for Anne to this day. As in the play, Henry visits Anne in the Tower, and as in the play, she lies to him about her fidelity to him. In the movie, however, she embellishes her lie with more detail, and pierces his manhood with even sharper arrows:

Yes, it’s overblown. And utterly without historical foundation. It was all invention. But—as Hillary Mantel said, “We always write out of our own time.” And the Tower Speech invention was of a particularly potent and timely sort for 1969. This was a period of convention-smashing in film: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Midnight Cowboy, The Wild Bunch, Butch Cassidy, and Easy Rider. But with the exception of Bonnie Parker and Mrs. Robinson (but strikingly not her daughter Elaine), the female characters in the New American Cinema played by the rules. It was the men who challenged the “status quo,” and the men who paid heroically for it. 4Hale and Boland’s Anne, long before Thelma and Louise, is the first female heroine to ride off the cliff, in full consciousness of what she is doing, to preserve her own integrity (and in this case, the future of her daughter and of England).

It struck a chord, even with me. In 1969, I was a pretty cynical movie-goer. The anti-sentimentalist Pauline Kael, who did movie reviews for The New Yorker, was my idol, and I hated anything that smacked of pretention or high-mindedness. I was not a feminist in anything but the most inchoate sense of the word. While friends of mine were joining consciousness-raising groups and attending demonstrations, I scorned and was made anxious by what I thought of as “groupthink.” My own personal rebellion was to drop out of school, have a lot of mindless sex, marry someone I didn’t love, and then suffer a nervous breakdown which made me unable to leave him.

But I did manage to make it to the movies—and Anne of the Thousand Days was one of them. It was my first introduction, since the boring, sexless Tudor history I’d read in high school, to the story of Henry and Anne. I had no idea what was invented and what was historically documented, but it made no difference. I loved fiery, rebellious Anne. I loved the way she bossed Richard Burton’s Henry around like a surly, 20th-century teenager. I loved the fact that Genevieve Bujold’s hair was messy as she delivered that speech to Henry, loved her intensity, loved her less-than-perfectly symmetrical beauty, loved the fact that someone that small could pack such a wallop.

Anne’s speech in the Tower might have seemed melodramatic if it had been played by a young Bette Davis—or, heaven forfend, an Elizabeth Taylor! But Bujold’s fire, issuing from her petite frame and elfin face, her hair disheveled, her dark eyes glittering with pride, desperation, hurt, and vengeance, transformed the potentially hokey into an indelible, iconic moment. Even at a recent festival of Burton’s films, held by the British Film Institute, the audience was stirred, crying out “Go, Anne, go, you tell him!”

“After watching this,” writes one contemporary Tudorphile, “you come away with the feeling that if that ain’t the way it really happened then it should’ve. I love the pride she displays even after Henry slaps her. She’s right, he’s wrong and they both know it. As she goes on talking down to him you can see him shriveling little by little and he nevermore was the man he’d once been. Seems she got the last laugh in more ways than one.”

Bujold also did something with Anne’s famous — and famously ambiguous — behavior in the Tower that contributed to the believability of that final speech. Anne’s actions and comments, as she awaited her sentencing and then her death, provide some of the most intriguing clues to her personality. Unfortunately, they were recorded for Thomas Cromwell by Constable Kingston a man who seems to have been tone-deaf to her sense of irony.

In one iconic moment, for example, Anne had said to Kingston, upon arrival at the Tower and being told that she would be housed in the apartment she stayed in before her coronation, that it is “too good for her.” Kingston reports that she then “kneeled down weeping, and in the same sorrow fell into a great laughing.”One can interpret the weeping as relief and the laughter as hysterical, but Anne also laughed —in the same conversation with Kingston—when he told her that “even the King’s poorest subject hath justice.” It’s hard to read that laughter as anything other than mocking Kingston’s naivete about the King’s “justice.” Similarly, Anne’s laughter over being housed in her coronation room can be read as a reaction to the bizarre, bitter irony of her situation. For a queen, of course, the apartment would hardly be “too good.” By saying so, Anne may have been pointing out to the clueless, uncomfortable Kingston that she was still, after all, the queen of England.

These are matters of interpretation that can make a huge difference

in an actress’s portrayal of Anne. When Anne delivered her best-known

line—“I heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck”—then put her hands around her neck and “laughed heartily” (as Kingston described it), he took her to be showing “much joy and pleasure in death.” The actresses who have played Anne have been too smart to accept that interpretation, but then they have been left with the task of figuring out just what was going on. Merle Oberon and Dorothy Tutin eliminate the laughter entirely and have Anne say the line wistfully, as if in resigned acceptance (and in the case of Oberon., with a touch of narcissism) of the reality of the coming confrontation between steel and flesh. Natalie Dormer plays the “little neck” speech as a moment when the unimaginable stress that Anne is enduring breaks through her composure, and both the absurdity and the terror of her situation erupt in a crazy joke and then, hysterical laughter — an interpretation that fits well with the evidence that Anne’s behavior in the tower was frequently unhinged. But Bujold chooses to emphasize Anne’s intelligence and pride rather than her emotional instability, and plays the line as a sardonic response to Kingston’s lame reassurances that the blow would be so “subtle” there would be no pain. Her Anne recognizes cowardly, self-serving bull when it’s thrown at her, and will have none of it. She was, and probably always will be, the proudest of Annes.

…..Bujold’s own history had prepared her well to play a young woman breaking through the confinements of convention. She had grown up in a devout French-Canadian Catholic household, and spent her first twelve school years in a convent; in an online biography, she is quoted as saying that at the time she felt “as if I were in a long, dark tunnel, trying to convince myself that if I could ever get out, there was light ahead.” But something about her religious training made its way into her attitude toward acting. When asked in 2007 how she prepared for her roles, she answered, “You pray for grace. If you’ve done your homework and, most of all, are open to receive, you go forward…Preparation for me is sacred.” But going forward with her own life required rebellion as well as grace; she finally “got out’ of the tunnel by being caught reading a forbidden book. Liberated to pursue her own designs for her life, she enrolled in Montreal’s free Conservatoire d’Art Dramatique.” While on tour in Paris with the company, she was discovered by director Alain Resnais, who cast her with Yves Montand in the acclaimed La Guerre est Finie.

Resnais taught her an acting lesson that “still is in me, will always be with me. ‘Always go to the end of your movement,’ he told me”–don’t short-circuit the emotion, the bodily expression, the commitments of the personality you are playing, allow them to fully unfold. That’s something that Genevieve saw in Anne as well. “You can’t put something into a character,” she said, “that you haven’t got within you. Every little thing in life is fed into the character…A word, a thought. I had read something on Anne Boleyn that Hal gave me and I could look at her with joy and energy; Anne brought a smile to my face.” I asked her what elicited that smile. “Independence. A healthy sense of justice. And she knew herself and was well with herself. She obviously had such profound integrity in that respect. She was willing to lose her head to go to the end of her movement.” That’s what we see, too, in her portrayal of Anne, especially in that final speech, and it’s why “My Elizabeth shall be queen!” still has audiences cheering for her, unconcerned with the historical liberties.

Before I said good-by to Genevieve in our interview, I asked her who she would pick to play Anne today. She admitted that she hadn’t seen either Natalie Portman or Natalie Dormer; she lives a fairly reclusive life in Malibu, and rarely sees movies or watches television. “But is there anyone who you think would do the part justice?” She was silent for awhile, then asked me if she could be honest. Of course, I said. “Maybe it’s selfish, but…the way I feel….” Genevieve had been so warm and generous throughout the interview, praising all her mentors and influences in her life, she was clearly a bit uncomfortable with what she wanted to say. So, I pressed a bit more, and she responded, with an intensity that recalled her performance and made me smile with delight.

“No-one,” she replied, “Anne is mine.”

BONUS!! Photo Gallery: Behind the Scenes and on the Set of “Anne of the Thousand Days”: Click HERE.

Also see:

How Courtly Love Betrayed Anne Boleyn

There are a number of theories as to what allowed the unthinkable—the state-ordered execution of a Queen—to happen. One theory, first advanced by Retha Warnicke and adopted by a number of novels and media depictions, is that the miscarried fetus was grossly deformed, which led to suspicions of witchcraft. But a…

“Perfectly preposterous”; “A Wikipedia entry with boobs,” declared the British media critics. David Starkey, one of the Grand Deans of Tudor history (and a self-confessed “all-purpose media tart”), called the series “gratuitously awful.”

Michael Hirst, the creator and writer of The Tudors, acknowledged in an interview with me that the first season didn’t do justice to Anne’s character and that “we probably had too much sex in the beginning” (a bit of an understatement). But the series is hardly “dumbed down,” as some critics objected. And as Hirst pointed out, The Tudors got trashed for its gaps and inventions, while Wolf Hall got nothing but praise, despite its liberties with history. Wolf Hall, Hirst said, not without some justice, is “complete fiction. But nobody says that. They all say: ‘What a wonderful book, what insights it brings to the Tudors.’ Isn’t that bizarre?”

He so succeeded in this goal that Queen Elizabeth II, at a 1972 Royal Command Performance of Anne of the Thousand Days, shook his hand and whis-

pered, “Thank you, Mr. Wallis. We’re learning about English history

from your films.”

When Wallis first suggested it to Paramount execs, they had balked. Charles Bluhdorn, who owned Paramount, could not see how mass audiences would accept a “plot predicated on what was es- sentially an intellectual argument.” It was only after Wallis reassured him that he would dress up the intellectual content with beautiful locations and gorgeous costumes that Bluhdorn agreed. The movie went on to receive ten oscar nominations and encouraged Wallis’s ambition to make a series of historical dramas.

Although nowadays, pop culture tends to call the shots on “reality,” it used to be that it took awhile for movies to catch up with events in the real world. In 1969, Women’s Liberation groups were forming all over the country. But it would be another five years or so before films like Scorcese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Her Anymore and Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman would bow, gently, in the direction of a “new woman.” It wouldn’t be until Thelma and Louise (1991) that the deepest gender conventions would be challenged. In Alice and Unmarried Woman, the heroines’ (Ellen Burstyn and Jill Clayburgh) independence is tempered by the presence of two gorgeous, really nice guys (Kris Kristofferson and Alan Bates, each at the height of his appeal) who, it is implied, will remain in the women’s lives, providing support and great sex while the heroines pursue their careers. In Thelma and Louise, in contrast, even the nicest of the male characters are impotent; despite every attempt, they cannot alter the tragic course of events. The women have chosen, and they—like the rebel-males of the 1968-9 films—will have to pay the price

Wonderful piece. How have I missed this movie? “Always go to the end of your movement” is great advice for writers, too—although I’d add “and not a word longer.”

I find it interesting how Anne Boleyn has become one of the more fascinating people in history. That women fight to represent her. I think she has been terribly maligned in history until recently. I feel that it was her strength that was her undoing because of the times she lived in, and the callous people who inhabited her circle.

Thank you for this very interesting post.