My Daughter, My Teacher

My husband once gave me dish-towels for Christmas. To say I was hurt would be an understatement. But there was something I didn’t realize then that I do now. And it was my daughter who opened my eyes.

Edward, Part One: Dish-Towels

Christmas morning ten years ago my darling, clueless husband gave me dishtowels for Christmas. And couldn’t figure out why I looked so crestfallen and was in a foul snit for the rest of the day. In truth, it was more than a snit. I was heart-broken. Dishtowels? Was he being passive-aggressive? Or did he just not care about making me happy, feel appreciated, experience delight? To add stinging insult to injury, he had first put the dishtowels in a box that formerly had held printing paper (which would have been bad enough), wrapped it up, then put the whole thing in an Hermes shopping bag!! Hermes!! (He’d been to Paris earlier that year.) It wasn’t quite as bad as Emma Thompson getting a Joni Mitchell album instead of the necklace she’d expected (and that in fact was given to her husband’s flirty secretary) but it was pretty bad.

By last Christmas, we were laughing about it—among less utilitarian gifts, Cassie gave me dishtowels with quotations from “Schitt’s Creek” on them as a reminder. But that original dishtowels morning, I was crushed.

It wasn’t the first time my husband had hurt my feelings by seeming so oblivious to them. But since then, I learned something I didn’t know ten years ago.

From the beginning of our relationship, I was both charmed by Edward and perplexed by him. I saw everything about him as sweet and unique—because I was so in love with him, but also because he was so different from me. In those days, being “me” was mostly feeling like a mess—gotten me into a marriage I regretted as I was walking down the aisle, then into a nervous breakdown, then into the beds of lots of men whose names I can’t even remember. I smoked two packs of cigarettes a day. Thank goodness I quit “in time” so as not to suffer significant damage to my lungs (at least, at 77, not so far.)

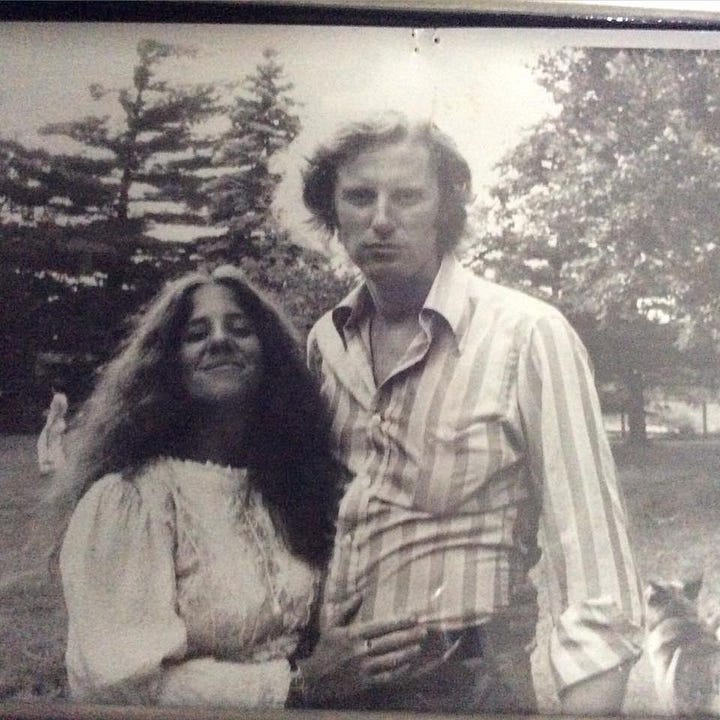

Edward was what my parents (admiringly) called “reserved.” Self-contained, everything he did had a deliberateness about it. No excess—nothing like me, who went overboard no matter what I did. His handwriting was the tiniest I’d ever seen, and he’d fill up a page from top to bottom with very little space in-between the lines before he’d submit to using a new sheet. He cooked the same thing for breakfast and dinner every day (eggs and toast in the morning; chicken at night) and wore the same tan car-coat he’d worn in high school. It was badly in need of dry-cleaning, its fake-fur collar coming slightly detached at the edge, and I fell in love with him (no idea at the time who he was) when I saw him in that coat in the corner of an elevator at the university where he taught Russian language and literature and I was a part-time student, part-time secretary in Philosophy. I met him for real later that week at a party hosted by the chair of the Russian department. I was newly separated from my first husband; Edward was single. I’m not sure, but it might have been a set-up.

I was startled by his one-room, basement apartment, not because it was tiny and dark (which it was) but because it was almost entirely inhabited by a baby grand piano and cardboard boxes of clothes. He explained that he saw “no purpose” in getting a dresser; cardboard boxes piled on top of each other would do just as well, in his opinion. (It wasn’t a money thing; he was an assistant professor and could have afforded a piece of furniture for his clothes—which were minimal, and dated.) He cooked his fried eggs always the same way—with a cover on them in order to seal the yolk while avoiding the chaos of splattering butter. Then he’d put each egg on one piece of toast and neatly cut the combo in four identical pieces. I was so infatuated with him that I, an excellent cook, told him “This is the best meal I’ve ever had!” “You’re too kind,” he said, sounding very much like his father Boardie, who was the Platonic form of the gentleman WASP.

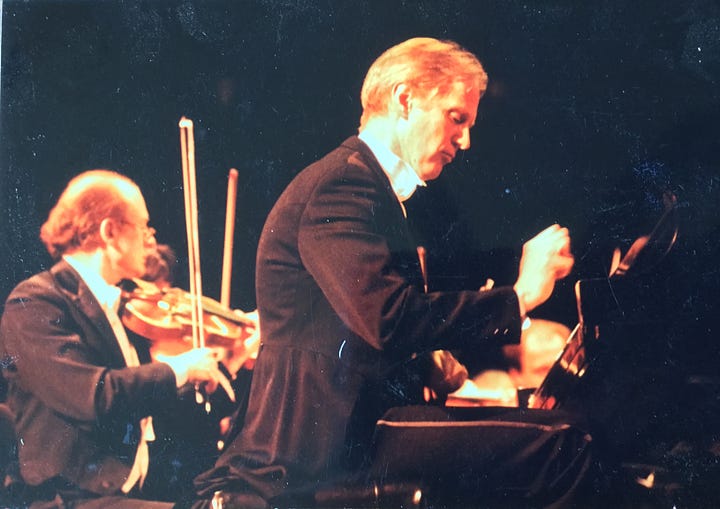

I said “no excess.” But that was only true until he sat down to play Scriabin or Rachmaninov at the baby grand piano that filled up the entire kitchen space, or when he spoke in Russian. When he played he became a nineteenth century romantic hero (the long hair fashionable then helped) but without the consumption. When he spoke Russian his accent was so perfect that despite his tall, very American-in-the-style-of Sam Shepherd good looks he sometimes got taken for a native. You’ve seen “A Fish Called Wanda”? Then you know.

On our first date he played Scriabin for me and recited a poem in Russian. And we talked about Pauline Kael and Robert Altman and Anna Karenina all night.

But. But. When I called him in Ithaca (his home town) during the first school vacation we were apart and told him I missed him, he didn’t reciprocate, and I could feel his discomfort through the phone. He stiffened whenever I spontaneously hugged him. He never reached out to initiate an embrace. He never said “I love you.” At home and on vacation, he always had his practice (silent) piano keyboard on his lap, so it was physically impossible for us to sit close to each other and just cuddle. And when he wasn’t playing the keyboard, he was silently practicing Russian (and later, French.) I could see his mouth moving the words. I literally had to teach him that it was a nice thing to call your partner on the telephone and let her know how you were and ask how she was when you were away for any length of time.

I knew, from the rare times that he spoke to me directly about his feelings—we had many great conversations, but always dressed in the language of literature or ideas—that he often felt like an alien being among other members of the university faculty. He adored teaching, and his students adored him; the rules of relationship were clear and, like the Russian language itself, or like the piano, he practiced them to perfection. But in social settings other than the classroom, he often said things that were perfectly clear to him but that he could see others found odd, enigmatic.

I loved him then and I love him dearly now. But I almost left him several times.

When he gave me those dishtowels, the time for leaving was long past. We had a daughter, dogs, cats, birds, a house, the unusual luck of teaching jobs at the same university, and our lives were thoroughly intertwined.

I could still be heartbroken, though.

And then my daughter taught me something I wish I’d known decades ago.

Cassie.

In the Apple TV+ series “Lessons in Chemistry,” Elizabeth Zott (Brie Larson) thinking she’s likely pregnant, goes after-hours to the Hastings Research Institute where she works as a laboratory technician and steals two frogs. She takes them home, puts each one in a labelled glass container—one marked “control” and the other “experimental”—prepares a hypodermic needle (containing, we presume, her urine) and injects the one destined to be “experimental.” After some time, she takes the cover off the glass containers. “Experimental” has begun to ovulate and is shedding eggs. Elizabeth is pregnant.

Elizabeth is a dedicated, brilliant scientist. But she’s socially awkward and perplexed by the strange ways of most other humans, and they find her weird and off-putting. As Bonnie Garmus, author of the book on which the series is based, describes her, besides her brilliance she also had “a sort of blindness, and naturally that gets her in trouble….Elizabeth does not have the time or inclination to people-please. She also has no room for avoidance, manipulation, lies, and fakery. Seems like a lot of extra work. Why not just state facts? Why not just tell it like it is?” Many viewers of the series were reminded of some other fictional characters: forensic anthropologist Temperance “Bones” Brennon (Emily Deschanel), detective Elise Wassermann (Clemence Poesy) of “The Tunnel” (based on Sonya Cross—played by Diana Kruger— from the original Swedish series, “The Bridge”), and most recently, chess wizard Elizabeth “Beth” Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) of “The Queen’s Gambit”1

Watching the scene (which isn’t in Bonnie Garmus’s book) I likely had the same expression on my face when my daughter, who works on a farm, came home and described twisting a dead sheep’s head and then cutting the carcass up with her co-workers. She hadn’t killed the sheep (it had a heart attack in transport) but it certainly didn’t bother her to help turn a once-living creature into chops.

It wasn’t just my daughter’s familiarity with life and death on a farm that made her so much less squeamish than I am (not to mention less hypocritical, as I’d eat those chops if they came to me wrapped by the butcher at Fresh Market. ) When she was in third grade, her class had a field trip to a Native American history fair up near Red River gorge. One of the “hands-on” exhibits was a deer that the children were given instructions in skinning and then had the opportunity to do themselves. While the other little nine-year-old girls ran away, pretend vomiting, Cassie eagerly stepped up. People who hunted for survival had done it on that land for centuries; why would she turn away from it? She just didn’t get what the problem was. Now, at 25, there’s no kind of animal injury or illness, no procedure that the vet needs help with, no matter how bloody or gruesome, that she runs from. If she’s needed, she’s right there.

After the frog episode on “Lessons in Chemistry,” I asked Cassie if she’d ever dissected a frog at school—something that was part of the science curriculum when I was growing up and that I avoided by employing my thermometer-on- the-radiator trick. She said they hadn’t been expected to do that, but surprised me by saying she wouldn’t have been willing to do it. “What purpose would it have had?” she asked. Cutting up an already-dead sheep had purpose; pinning down and cutting open a squirming frog just so some kids could see its innards for real did not. She felt the same way (“what for?”) about pretty much everything they were expected to do in school, both curricularly and socially. It was “so much effort,” she told me, to figure out what other people were really thinking or wanting (“I don’t like having to read between the lines”) and when it came to conventional expectations of girls, she couldn’t see the point of most of it. I’d come to pick her up at school and sitting where she couldn’t see me, I’d watch her come down the side of the hall, downcast eyes, avoiding the small groups of chatterers that filled the middle.

Most teachers didn’t get her, and she didn’t get them. She started out as a wonderful reader, but was largely uninterested in anything they were reading about. And when she was uninterested, she couldn’t perform on demand—which then got interpreted as belligerence.

The fact that Cassie lost interest in reading concerned me. That’s a way of putting it that’s too kind to me—I was really, really upset that she hated reading. I had been a child that might have been in a permanent state of depression if it wasn’t for the local library, so it was hard for me to “get” how different it was for her. She was such an excellent reader—and had been since she was a toddler. I didn’t understand at the time that sheer ability didn’t necessarily translate to “can do it.” In fact, Cassie couldn’t stay focused on words and didn’t even want to try, not because she literally couldn’t read, but because they didn’t hold her attention, which drifted elsewhere.

My older sister Mickey Silverman, a therapist who worked a lot with children, suggested I have her tested for ADHD. So I did, and was told she tested “way too smart” for that diagnosis. He was an idiot.

By the time she was properly diagnosed by a better therapist, she hated most teachers, hated school, and eventually was expelled from high school for two mild outbursts of anger and (three strikes you’re out at that school) when they found a substantial amount of alcohol and weed in her car. Some of it was Cassie’s, but most of it belonged to her friends, who didn’t want it in their rooms. Cassie can’t say no to friends, and she wouldn’t let me name names. The thought of betraying hard-won friendships horrified her. Didn’t matter to the Dean. (I‘ll leave you to imagine what her hot-headed mother said to him.)

Through it all, she was quietly absorbing all the knowledge and skills that did make sense to her, that did “have purpose” for her. And she became a kind of genius at those things. When she was sixteen and got her learner’s permit, she astounded her father and me by immediately knowing how to drive—stick shift!—without one lesson. “I’ve just been watching you guys,” she told us. She can pretty much put anything together without even reading the directions. She “sees” with the eyes of a mechanic: she knows what parts will fit and what parts won’t, just by looking. She still hates reading. But if the words are on a set of instructions? She reads and absorbs them with the speed of lightning. If you want to figure out how something works? Put together a bird cage or a piece of IKEA furniture? Thank goodness Cassie is in the house.

But most magical of her super-powers is her genius with animals, particularly horses, who she’s loved, tended, and ridden since she was four and now cares for on a thoroughbred farm. And here’s the thing: The more “difficult” the horse, the more she is drawn to them. She understands—deeply understands—that what gets seen by some as willfully disobedient is just the struggling nature of a special, wild being in need of being understood and loved for exactly who they are. She not only knows just about everything there is to know in “normal” ways, but can interpret/intuit everything a horse is feeling, wanting, or afraid of. “What makes you so good at that?” I asked her. “I pay attention to the whole of them,” she said.

.

Edward, Part Two: The Pizza Oven

Cassie proudly considers herself “neurodivergent,” and I certainly recognize in her many of the qualities I’ve read about. Often, neurodivergent people are brilliant in some way (in fact, perhaps that’s a bit of a cliche at this point.) Often, they aren’t big huggers. (When she was tiny, Cassie wouldn’t cling to me when I picked her up, the way other babies put their arms around their moms and let themselves be carried.) They find it hard to “read” other people, and expend a lot of time and anxiety trying to figure out how to relate to those who have a more “typical” ease in relationships. They aren’t good pretenders, and carry on their bodies/in their faces disappointment and depression about the cruelty and/or stupidity around them. Which may make them be seen as angry, arrogant, distant. But when you win their trust, it’s precious and enduring.

In the 1970’s, when Edward and I met, there were so many things we had no names for. And without names, we stood baffled and blinking and hurt and angry and blaming and mistreated. There was no word for “sexual harassment” or “date rape”—and so, girls and women struggled together in consciousness-raising groups and in poetry and memoir to find our own ways of understanding and speaking about our shame and helpless fury. My panic disorder, which descended on me shortly after my first marriage, was chalked up by therapists to “inability to accommodate to the feminine role.” Those who were more biologically-minded treated me with anti-psychotic drugs that dried my mouth and clogged my mind (the part of me I needed most to save me.)

In those days, too, most medical professionals didn’t think in terms of spectrums but individual “pathologies” that were often theorized inadequately: “Autism” was identified with the most extreme ends of what we now know is a range of neurologically atypical behavior and experience. ADD, which we now think of as manifesting itself in a variety of ways, was reduced to “hyper-activity” and generally thought to only effect boys. We didn’t conceptualize eating, body, and weight disorders in terms of a continuum, but focused on (a limited idea about) “anorexia” whose diagnosis requested self-starvation, emaciation, and seeing yourself as fat no matter how skinny you got. And so on.

One day, when Cassie and I were laughing affectionately over some of Edward’s more unusual habits, she said to me: “Well you know, Da is an Aspie, don’t you?”

Actually no, it hadn’t crossed my mind. I’m not big on labels, for one thing, and when Edward and I met, the concept of “neurodiversity” just…wasn’t. For the first few years we were together, my baseline narrative when his detachment and self-absorption had hurt my feelings was that, like Katie from “The Way Things Were,” I just wasn’t the “right kind” of attractive for my Hubbell. Sure, he loved my brains and my vitality. But his paradigm of “desirable woman” was still the country-club WASPs that he’d grown up with: sporty, slender, cool in temperament. I was too passionate, too needy, too emotional, too hot-blooded. Later in the relationship, I speculated that there was something lacking in his own upbringing; I never met his mother but I knew his father and his brother and there wasn’t a whole lot of gemutlich there. I never imagined our differences to be neurologically-based, even partially.

But now that Cassie had said it, it made so much sense. Those dish-towels, for example. When I opened that box, I had been so ready to let my own insecurities take over that I’d forgotten how flooded and flummoxed Edward became whenever he was required to pick out a gift for someone. I was so good at it; for me, who spent a great deal of time thinking about the psyches and emotional lives of other people, it was the best part of giving presents, figuring out what would make the other person happy. But for Edward, that part is the hardest of all. Rather than risk failure, better to take the path of least resistance and go with something, like skinning that already-dead deer, that had a clear “purpose.” To know exactly what to do soothed his soul.2 When we took ballroom dancing together, he wouldn’t rumba, waltz or foxtrot with me until he had learned by heart every step in the routines we learned at Arthur Murray. “Come on, we know some stuff. Let’s just get up and dance!” I’d beg. No way.

One Christmas, having figured out that kitchen accessories were not the way way to go, Edward struck gold and bought me a gorgeous wrist cuff from the Museum of Modern Art catalogue. He was so delighted that he’d “gotten it right” that for the next four years he got me versions of exactly the same cuff.

This year, with our bank accounts getting depleted from my retirement and Cassie’s expensive horse-life, we conferenced about where we were spending unnecessary money. Edward suggested that one problem was that ever since COVID we’d gotten in the habit of doing way too much ordering in from restaurants. “Yeah,” I said, “but there’s a problem with that. The alternative, since Cassie doesn’t come home from work until late and you don’t cook is that I make all our dinners again.” (As I used to, for the sake of all our nutritional needs and patience: Edward following a recipe for lasagna—or even just putting together a jar of sauce and boxes of pasta—would have us eating at midnight.) “Hmmm,” he said, “I see the problem.” And we left it at that, unsolved.

In our house, with one Jewish parent and one Protestant parent, we celebrate Hanukkah and Christmas, so Cassie makes out “like a bandit,” with 8 nights of little gifts and one morning of “big” presents. But Edward and I only exchange gifts on Christmas—deciding what to get me for 8 straight nights would bring on a psychotic break in Edward. He was really excited, though, about what he got me for Christmas this year. Excited, but with trepidation. “Now you have to understand,” he said as he opened the box himself, “this isn’t exactly for right now, and we’ll have to prepare and learn some things first.”

That didn’t sound like much fun. Were we in for a new iteration of the dish-towels?

No. It was a portable pizza oven, and Edward presented it to me with a “Fresh Market” bag full of every conceivable dough mix, topping, pizza sauce, and cheese. There were multiple varieties of everything, so as not to get anything “wrong.” He had scoured the shelves, looking for all conceivable ingredients. And he had read all the directions with the same care he takes with piano scores. The thought of him going up and down the aisles, challenged, perplexed, but committed, almost brought me to tears.

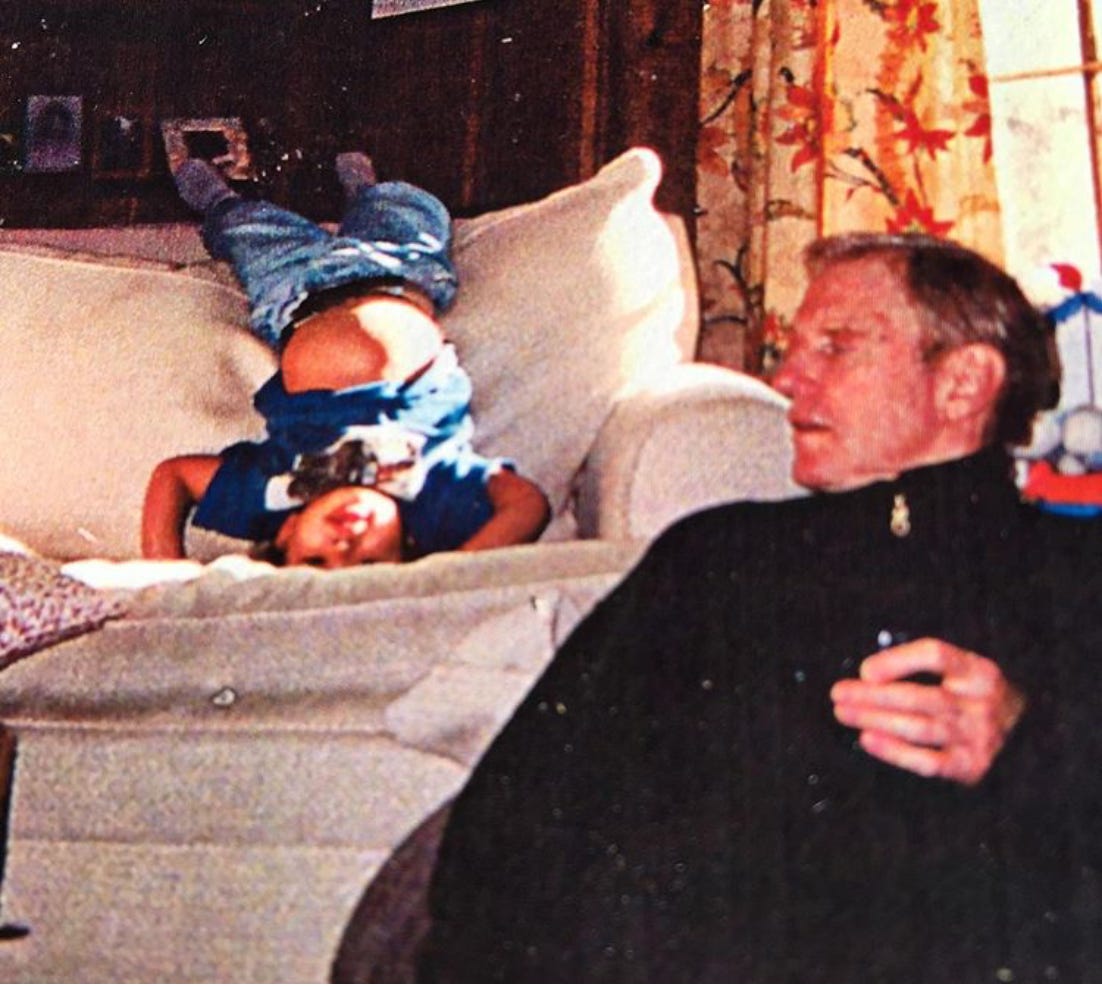

Proudly, he recited a dozen things about making pizza and plugging in and caring for small appliances that I’d known most of my adult life, while Cassie and I smiled at each other. Like, hadn’t he ever noticed that I kind of knew my way around a kitchen? Part of the delight of having a daughter is such shared secret, deep knowledge of the same man.

Despite the lecture form of his discourse, Edward wasn’t actually teaching me how to use the oven. He was showing me that he was learning himself. And of course, Edward being who he is, that meant avoiding mistakes and potential chaos of every possible kind. “Look,” he pointed out to us on the brochure, “they even have direction for special pizzas from all the different regions of Italy!” Cassie and I smiled at each other again. (“Wow! Recipes! Who’d have thought?”) It might take him a month or so to decide which to try first, he might be reading those directions over and over before he’d actually attempt to make a pie. But eventually I wouldn’t be the only one cooking dinner.

Like dishtowels, the oven had a practical purpose. But this time I knew I was loved.

For more on “Lessons in Chemistry,” see my stack:

By the way, Edward is the only one in the house who ever uses dishtowels, as he dislikes the dishwasher and can’t be convinced it’s the more ecologically sound alternative.

To everyone to whom I haven’t responded yet: Don’t think your comment has fallen into a well of inattention. I read and appreciate every comment, and WILL respond. Sometimes it just takes me a little longer. Hugs and thank you for your engagement and contributions. Love, Susan.

Oh my goodness you are so loved. I learned along time ago that I was never to rely on presents of any kind. In fact, I had taken to simply buying my own presents and letting the husband know what I bought and to tell him not to worry.

I figured that I have an honest, hardworking, loving father and husband who handed me his paycheck, left the running of everything to me. If he couldn’t figure out how to buy me a present I didn’t care. Thinking back the only time I got any jewelry was when the boys aide took them shopping for my birthday and she called the hubby while they were at the jewelry store.

Life is very different when you are surrounded by the neurodivergent. It makes things frustrating and interesting and amazing all at the same time.

You sound like 1 big wonderful family.