“Anora” Part I: Deconstructing the Rom-Com

“Anora” is often described as “A Modern-Day Pretty Woman.” And yes, there’s the “sex-worker-meets-rich-guy” commonality. But dive deeper into that trope and you won’t find an update but a demolition.

My cards—and my heart—on the table: I love “Anora” and I’m hoping that for the first time in many years my choice will be in step with the Academy’s. I’d stopped expecting that, and you can read about why in past stacks.1 But this year, I have some hope—perhaps because I have to have hope about something.

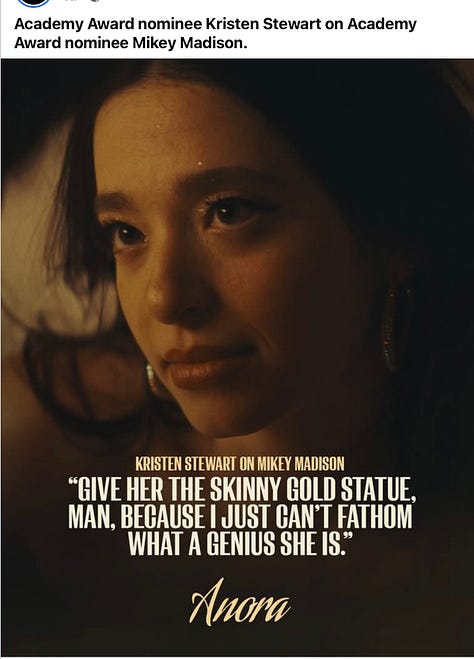

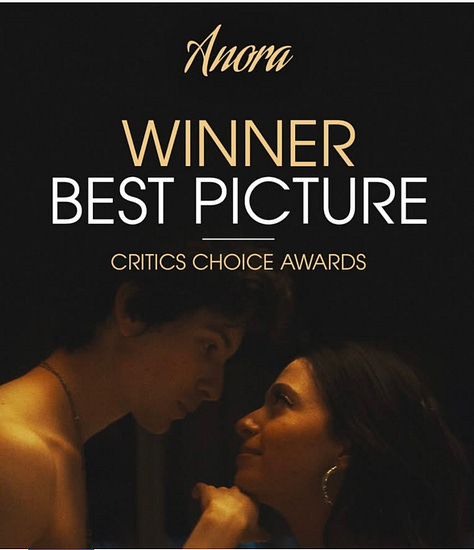

As “buzz” has been increasing over the past few weeks, so much has already been written about “Anora” that I’d become to wonder what new I can contribute. But putting my cultural historian, feminist, and movie-lover hats together and after indulging in days of watching and re-watching, I found a few things. Next week, I’ll write about all my Oscar “picks and pans.” This week is for my girl “Anora.” She seems to be a lot of other people’s girl too:

Many accolades. Yet a certain number of people whose views I take seriously didn’t like the movie. The found it disjointed, hectic, and too genre-hopping (Is it a slapstick comedy or drama? Is it just an update of “Pretty Woman” with naked bodies? A lot of noise and “mishegoss”?—as one FB friend put it.) I understand those reactions and have no interest in changing anyones mind. But I thought, rather than repeat what has already been said in other reviews, that I’d address some of those responses here.

[NOTE: No spoiler for the final scenes of “Anora,” which I’ll discuss in my next stack.]

Anora , Pretty Woman, and the Difference Between Rom Com and Screwball Comedy

It makes for some good review headlines:

“Sean Baker’s ‘Pretty woman’ is a triumph,” “Mikey Madison’s Modern-Day Take on Pretty Woman is Dazzling,” “Mikey Madison Blazes in this very modern Pretty Woman tale,” etc.

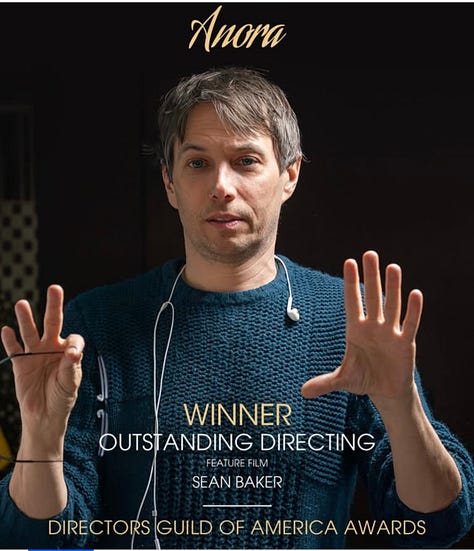

But writer/director Sean Baker wasn’t inspired by “Pretty Woman”—at least not consciously:

In September Baker told IndieWire : “Honestly, I didn’t even pick up on that until halfway through production and somebody called it out and I was like, ‘Oh, okay. Yeah, I see that.’ But I didn’t want it in any way to affect me. I didn’t want to be influenced by it. So I decided to not revisit it and to tell you the truth, I still haven’t revisited it, so I haven’t seen it since 1990.”

If you’re familiar with Baker’s films “Tangerine” and “The Florida Project,” (I haven’t seen “Red Rocket” yet) you’ll find a much clearer line from his own earlier work to “Anora” than from “Pretty Woman” to “Anora.” The central characters of “Tangerine” are two transgender sex workers: Sin-Dee (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez) is prowling the streets of West LA looking for her cheating boyfriend while her friend Alexandra (Mya Taylor) is picking up a little money while distributing flyers for her appearance that night at a local bar (she sings “Toyland”—and made me cry.) “The Florida Project” follows the adventures of Moonee (Brooklyn Prince), an imaginative, streetwise six-year-old whose laissez-faire mother Halley (Bria Vinaite), improvising ways to make her rent money, steals and sells tickets to Disneyland and has sex with men in her motel room. Both films, like “Anora,” are no-limits raunchy, funny, warm, and have segments of everyone-talking-loud-at-once chaos and physical slapstick, then unexpected turns that will haunt you forever. Running through the psyche of all three films are fantasy-worlds imagined as escapes from the sober, crushing realities of hardluck adult life (“ToyLand,” the Disneyworld Castle, which figures in “The Florida Project, Las Vegas the the Zakharov Oceanside mansion in “Anora”). All of them end ambiguously and movingly. “Tangerine” and “The Florida Project” feel, in many ways, like preparation for “Anora.”

So Baker didn’t wake up one day thinking “Hey, what about a film about a sex worker with fairy-tale dreams!” But Baker, who was 19 when “Pretty Woman” was released and a movie buff from an early age, didn’t have to have seen it again for it to be stored somewhere in his memories. The film, and particularly its breakout star Julia Roberts, became (much to the surprise of the cast and director Garry Marshall) both a film and cultural sensation. Audiences were dazzled by Roberts’ mega-watt smile and natural instinct for seemingly unselfconscious charm. (Myself, I prefer her in “Mystic Pizza”—those big hips and slightly butch physicality were such a great combo—and “My Best Friend’s Wedding.”) The chemistry between her and Richard Gere was right. And in the 1980’s and early 90’s, Hollywood often tried to incorporate some version of feminism—often by featuring working women struggling with classism, sexism, and (less frequently until we were well into the 90’s) racism—into traditionally entertaining formats.2

You might be thinking: Feminist? “Pretty Woman”?? And for sure, there’s a lot that’s cringe-worthy in 2025–for example, the scene in which Edward’s lawyer William (Jason Alexander) tries to rape Vivian, slugs her face hard (I winced, even though I’d seen the movie many times before.) After Edward (Gere) comes to her rescue, he doesn’t seem to think a crime has been committed, even after Vivian says she feels like her eye is going to explode. Instead of calling the cops (or even the front desk) he puts ice on her cheek, tells her “not all men hit” (good for you, Edward) and engages in a conversation with William about their relationship. (William: “What is wrong with you ? Come on, Edward ! I gave you ten years ! I devoted my whole life to you !” Edward: “That's bullshit. This is such bullshit ! It's the kill you love, not me! I made you a very rich man doing exactly what you loved. Now get outta here ! Get out ! “)

Whatever we think in 2025–it’s not the main subject of this stack, so I’m not going to review the “is it progressive or regressive?” arguments here—the question of how to inject a little feminism into the fairy-tale plot (or at least, how not to rely on familiar sexist tropes) was a subject of concern among the makers of the film. Most notably, Laura Ziskin, the executive producer of the film, wanted the knight-on-horseback finale to end on a note of “equality”—and suggested a line to take care of it:

It’s not untrue to the plot, in which Vivian’s warmth and spontaneity does “rescue” Edward from his life as a work-obsessed head of a company that buys floundering businesses and sells them for parts. But face it, in 2025, it does feel tacked on to make the schmaltzy but entertaining scene more politically correct. The deliberateness seems borne out by the insistence by various members of the creative team (in a 2020 documentary on the movie): “She’s the one making decisions now,” “She’s evolved,” “It’s princess culture coming together with feminist culture.”

Hmmm. Maybe a tad more princess culture than feminist culture. (Or maybe more precisely Julia Roberts culture; every woman wanted her tousled hairstyle, long legs, and gorgeous outfits in the film.)

But interestingly, the original screenplay didn’t even have a fairy tale ending in need of feminist tweaking:

Although Pretty Woman is now one of the most popular romantic comedies in the world, the original screenplay did not have a happy ending. In the version written by J.F. Lawton…wanted to use his script to call out the race by big American companies and Wall Street to make as much money as humanly possible. The idea was to draw a parallel between Edward’s greed and Vivian’s complicated and disjointed life, which represented American society.

Far from creating a romantic comedy, J.F. Lawton had not considered a happy ending between the two protagonists. Originally called $3,000, the price for Vivian to spend the week with Edward…The businessman left the young woman on the pavement where they had met a few days earlier, throwing the promised cash out the window in exchange for her company. With the money, Vivian and her friend Kit went on a trip to Disneyland. The film ended tragically: on the way, Vivian, originally written as a drug addict, died of an overdose.

This was a very dark scenario. As a result, despite the backing of major institutions such as the Sundance Institute, the script struggled to garner much funding. Deemed too dramatic, the project remained in a rut for several months until Disney bought the rights and Garry Marshall was appointed director…”

Marshall was noted mostly for his work on popular television sitcoms like “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” “The Odd Couple,” “Happy Days,” and “Laverne and Shirley.” He was also collaborative and welcoming of any and all comic contributions, which he collected every day of shooting from anyone on set who thought they had a good joke to include. The eventual result:

[Through several rewrites and additions during production] the script was completely rehashed [and] the quintessential romantic comedy couple gradually took shape [with its] fairy-tale ending.

(Kate Erbland, “The True Story of Pretty Woman’s Original Dark Ending,” Vanity Fair, March 23, 2015)

So: When Peter Debruge, in Vanity Fair, describes “Anora” as “a subversively romantic, free-wheeling sex farce [that] makes ‘Pretty Woman’ look like a Disney movie,” it’s truer than he seems to be aware. “Pretty Woman” is—literally, not just metaphorically—a Disney movie. And “Anora” is neither. (If you are at all squeamish about the word “fuck,”some grammatical form is in virtually every sentence, nomatter who is talking.”) More deeply important, “Pretty Woman” is a Rom Com and “Anora” is not. It’s a screwball comedy.

The difference? Rom Coms follow the formula of classic (e.g. Shakespearean) comedies: There’s a first “act” of falling love (sometimes recognized by the characters, sometimes not), a second act in which misunderstandings, mistaken identities, personality or class differences, the interference of others, etc lead to obstacles to the relationship(s) and a lot of comic chaos. And a third act in which all obstacles are overcome and love (and usually, marriage) wins the day.

The classical comedy/Rom Com are thus celebrations of forever-after love and marriage. The screwball comedy—even when it end with the lovers in each others arms—satirizes, deconstructs, spoofs and in various ways “screws with” that ideal. (The term “screwball” is often mistakenly taken as meaning “wacky”—and for sure there are wacky elements in the humor of such comedies. But the term actually comes from baseball, when in the early part of the 20th century it referred to “any pitched ball that moves in an unusual or unexpected way.”) Expected in the classic comedy: the wedding and presumption of happily-ever-after. Unexpected: a cynical, world-wise “undertow” that winks at the naïveté of conventional fantasies. And often, conventional male/female roles.

So, for example, in a screwball comedy like Preston Sturges’ 1941 The Lady Eve, the female protagonist Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) is a confident, bold, and manipulative con artist while the rich man she ensnares, Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), although from a superior class, is bewitched, bewildered, and bumbling (many pratfalls for Fonda.) And although Jean genuinely falls for him, she never loses her edge over him, in knowledge or world-wisdom. In a sexually scandalous ending (it remains suggestive only, to avoid the Hayes Office), the two nuzzle and declare their love for each other, even though he still thinks that he’s already married to another woman. Jean, however, knows that “other woman” is, in reality, herself, disguised as “Eve.”

A more contemporary take on the screwball comedy, P.J. Hogan’s 1997 “My Best Friend’s Wedding” has a rambunctious and super-confident (“she’s toast”) Jules (Julia Roberts) scheming in every way imaginable to recapture the love of ex-boyfriend Michael (Dermot Mulroney) from sweet and submissive Kimmy (Cameron Diaz, another actress with a mega-watt smile.) She’s not successful. The movie ends with a wedding, but it’s Michael and Kimmy’s, and Jules is dejected, sitting alone, toying with her cake. But there’s compensation: her “sleek, stylish, and radiant with charisma” editor George (Rupert Everett) shows up at the wedding, pulls her to him, and leads her to the dance floor, where he dips and twirls her. George is gay (and at his gorgeous prime in this movie.) So the heroine doesn’t get the ring and the man, but—as George tells her—“by God, there will be dancing!” It’s not just the ending, however, that screws with (in this case, queers) conventions of happily-ever-after heterosexual relations. Hogan pokes at them throughout the movie.3

Anora has all the features of a classic screwball comedy. But it’s a comedy that’s hyper-aware of the realities of power.

“Anora was something we collectively felt we were transported by, we were moved by. It felt both new and in conversation with older forms of cinema. There was something about it that reminded us of [the] classic structures of [Ernst] Lubitsch or Howard Hawks, and then it did something completely truthful and unexpected." (Greta Gerwig, who served as president of this year's jury at the Cannes Film Festival, where the film won the Palme d’Or)

Anora—or “Ani,” as she prefers to be called, (played by the adorable tornado of talent Mikey Madison) is a lap dancer and sometimes more at a Manhattan strip club, where she meets and captivates Ivan/Vanya, the indulged but charming son (played by the “Russian Timothee Chalamet”, Mark Eydelshteyn) of a rich Russian oligarch. The owner of HQ has taken her to him because she speaks Russian. In fact, she can but doesn’t like to (her unpolished accent? A desire to assimilate? Not clear.) A Brighton Beach native of at least part-Russian background (she had a grandmother who could only speak Russian—a detail that made me remember my Yiddish-speaking grandma) she understands everything when it’s spoken.

Unlike Vivian in “Pretty Woman,” she’s no newcomer to the big city. She’s been at it for awhile, and is skilled and comfortable with the work. (In preparation for the role of Vivian, Julia Roberts hung out for a day with two sex workers; Mikey Madison immersed herself for months in dance-club culture, and also learned how to do an expert pole dance.) While Vivian’s country-bumpkin residue (which the script constantly emphasizes) reassured 1990 viewers that she’s “not really” a seasoned pro, Ani is unashamed and completely at home with her job. Sean Baker wants that from the viewer, too. As with “Tangerine” and “The Florida Project,” he neither judges, condescends, or exoticizes. When Ani enters the Zakharov mansion for the first time, he takes the viewer inside from her point of view, which is dazzled but composed. It’s Vanya who, because of his immaturity and struggle with English, seems awkward.

Vanya has a real good time with Ani, and hires her (15K—some major inflation since “Pretty Woman” but a virtually identical bargaining scene) to spend the week with him before he’s due to return to Russia and buckle down to work for his father’s business. They frolic and party, with Vanya behaving like a hyperactive toddler with a great new toy. Sexually (and in other ways) he’s still an adolescent. But after accepting his lack of slam-bam finesse for awhile, Ani takes the upper hand, teaching him to slow down.

It may be the first sex Vanya’s had that’s not a version of hurried, teenage masturbation (like a “spastic rabbit,” as one reviewer puts it) and he becomes so smitten that he asks Ani to marry him (and—bonus!—he’ll also get a green card as the husband of an American.) At first she doesn’t believe him—she doesn’t expect marriage proposals—but he seems to guileless and sweetly, inarticulately enthusiastic that it doesn’t take much to get her to agree. The proposal happens in a huge penthouse in Las Vegas, she’s watched as the manager of the hotel pampers Vanya; it’s become like a fairy-tale in which anything is possible. And after they marry, she begins to believe fully in its reality. She’s got the license, a ring, she’s a wife!

In “Act Two,” harsh reality crashes—hilariously for the viewer—into Ani’s possibility of an opulent, fun-filled life in the Disneyland of Zakharov’s oceanfront Brighton Beach mansion. Word gets back to his parents that their impulsive and frequently stoned son has gotten married. And—bozhe moy!—to a hooker! They dispatch Vanya’s Armenian godfather Toros (Karren Karagulian, who appears in all of Baker’s films, and has riders vomit in his car in two of them—which must have become an inside joke of some sort between Baker and Karagulian) to the mansion after his brother Garnick and Russian “muscle” Igor (Yura Borisov, who has been nominated for Best Supporting Actor) “invade” the mansion and let him know the rumors are true. When the parents find out they announce that they too are coming to America themselves to fetch their wayward son, who they are used to rescuing from disaster, and get him an annulment.

Ivan, hearing that his parents are on their way, runs away like a guilty and scared little kid who’s caught with his hand in the cookie-jar. He doesn’t give a second thought to the fact that he’s left the cookie behind. But this cookie is not so easily discarded. In the scenes that follow, Ani comes alive as a true screwball comedy heroine: fierce and fighting for what she wants.

The male brutality that might be expected from Russian henchmen (if this were a different sort of movie) never happens. No one wants to hurt her, just to keep her from running away (they need her to be present for the annulment.) But Ani, defiantly affronted and surprisingly strong (“Impressive!”says Igor after she slugs him) won’t be held down. Garnick’s nose is broken, the living room gets trashed, and Igor is forced to improvise ways to restrain Ani without hurting her. He’s huge, she’s 5 foot three, but she’s a match for him (“She doesn’t fight like a little girl”) partly because she’s so fearless, but also because Igor is so determined to keep her safe (something Ani can’t fathom, as the men she’s known at the club have other things than her protection on their minds.)

This—the “home invasion scene”—is the part that some of my Facebook friends found jarring, random, excessive “mishegoss.” I found it hilarious. (Can’t be captured in words; you’ll just have to see it.) It also provides a key transition. Sean Baker considered the 28-minute scene, which he arduously choreographed and later spent three months editing, to be essential: “It was about getting them to that place where she was willing to go out with them to look for Ivan, whether or not they were on the same page.” Cinematographer Drew Daniels adds that the scene takes us from “that feeling of exaltation, joy and happiness for [Ani] to: something is wrong and everything’s going to come to a halt.” In other words, the scene, while hilarious, is also deflating, bubble-bursting, as the beautiful wild horse that we’ve come to admire is ultimately subdued.

Subdued—but not broken, as Anora still has hopes that Vanya, once they’ve found him, will stand up for her and their marriage. And that hope persists, even after Toros has dragged them through all of Vanya’s Brighton Beach and Manhattan haunts and they’ve found him—in the club where he first met Anora—so inebriated that he can barely stand, much less defend Anora. That hope still persists even when the judge in Manhattan instructs them that they will have to go to Nevada for the annulment. And it still persists even in anticipation of the arrival of the parents, who Ani is sure will see how in love she and Vanya are and bless the union.

It’s perhaps with the arrival of the Zakharovs that Act three begins, signaled by the cold, queenly descent from the plane of another female force-of-nature, Ivan’s mother Galina (Darya Ekamasova.) She is the first of the characters whose strength of will matches that of Anora. But Galina has the power, not just of determination, but of money and status, and far from warmly welcoming Anora into the family, coldly reminds her of that. Anora resigns herself to the annulment, but not without a parting shot. “You are a disgusting hooker,” says Galina. Anora: “And your son hates you so much that he married one to piss you off.”

My “perhaps it’s the third act” comes from the fact that the annulment isn’t the end of the movie. As in the classic screwball ending, the Rom Com/Pretty Woman fantasy in which love and marriage (as the pop song from the fifties goes) “go together like a horse and carriage” is deconstructed—in this case, by the realities of power, privilege, and wealth that the Zakharovs represent. Unlike “The Lady Eve” and “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” the deconstruction doesn’t end on a comic note. But it doesn’t end with Anora’s snarky parting shot, either. There’s a “coda” to the annulment which also might be thought of as the real final act. And—like the last line of some brilliant short stories—it shifts our perceptions, feelings, and interpretations to a whole new register. It deserves an intimate response all its own, which I’m going to save for my next stack, on my pre-Oscar picks and predictions. I hope by then those of you who haven’t yet seen “Anora” will have, and that all readers will come to my discussion with your own interpretations.

.

See, as just one example, last year’s Oscar stack. In it, you’ll find references to other movie stacks as well.

Examples, some great and some not-so-great: “Baby Boom,” “Steel Magnolias,” “When Harry Met Sally,” “Working Girl,” “Mystic Pizza,” “St.Elmo’s Fire,” “Terms of Endearment,” “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” “Heathers,” “Say Anything,” “Out of Africa,” “Dirty Dancing,” “Desperately Seeking Susan,” “Blue Steel,” “Thelma and Louise,” “Silence of the Lambs,” “La Femme Nikita,” and all the John Hughes/Molly Ringwald movies.

For an extended version of my take on “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” see the chapter called “Gay Men’s Revenge” in my book The Male Body.

Susan, I also liked Anora very much. My favorite scenes were the manic ones where Anora and the Russians are trying to find Ivan. Everyone's shouting and cursing over each other and it just feels so real. I think those types of scenes are really hard to get right, the degree of difficulty is very high. But this movie pulled it off.

P.S. Fun Fact: Mikey Madison learned to pole dance and how to cop the attitude and speech patterns of a sex worker from Luna Miranda Sofia, who co-stars as her best friend in the film, and who is also my future daughter-in-law!