I’m Just Susan, and These are My Picks and Predictions

Best Picture and more, including a rarely mentioned fact about “Poor Things”

Best Picture:

My pick: “Barbie”

My runners-up: “Anatomy of a Fall” and “The Zone of Interest”

Likely winner: “Oppenheimer”

Possible winner: “Poor Things”

Once upon a time, it was “Barbenheimer.” Then something weird and predictable happened….

When they opened and were first reviewed, it seemed as though “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie” were going to be equal favorites in the Oscars horse-race. Both were big money-makers (“Oppenheimer” at first carried along on “Barbie” coat-tails.) Both, with a few exceptions, were critically praised. If anything, the reviews of “Barbie” had the edge on “Oppenheimer,” in part because of the surprise factor, especially among male viewers, who went in begrudging and skeptical and often came out smiling, dazed and seduced. By feminism!! Quite an achievement.

As the months went on, however, something changed. Did the heavily underlined profundities of “Oppenheimer” make “Barbie” start to seem like a confection? Could the whimsy of “Do you ever think about dying” compete against “And now I am become Death” (repeated twice in “Oppenheimer, “ once as an erotic stimulant, and then again, you know when.) How could the whimsical last line of “Barbie”—“I’m here to see my gynecologist!”—possibly win over the drama of the final scene in “Oppenheimer,” with Oppenheimer, recalling to Einstein how they’d “worried that we’d start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world”

“What of it?” Says Einstein.

Oppenheimer: “I believe we did.”

(Christopher Nolan’s script directions: Einstein pales, turns….Close in on my 1staring eyes as I visualize the EXPANDING NUCLEAR ARSENALS OF THE WORLD….When I can take it no longer, I jam my eyes closed and we—Cut to black.) [Caps are Nolan’s]

For more on the overbearing pomposity of “Oppenheimer” (and other issues I have with the film) see last week’s stack:

As for what I love about “Barbie,” I’ve already written quite a lot about that, including a recent stack on why the movie has been so badly “snubbed” (as a number of headlines have put it) by those handing out awards. So as not to repeat myself, I refer you to a couple of those pieces:

Writing the stack about the “snub” has helped calm me down. I’d been simmering for quite awhile over the cascade of awards lavished on “Oppenheimer” while the far more enjoyable, less pretentious, and more innovative “Barbie” was ignored.

Well, not exactly ignored. Rather, put in her place, bit by bit. First, the male-dominated group who decide on the nominations for the Academy Awards in writing ruled that Gerwig and Baumbach’s screenplay belonged in the “adapted” (rather than “original”) category because the movie “was based on a previously existing character.”

Then there were the Golden Globes, where “Barbie failed to win best comedy or musical but walked away with the cheesy, newly-invented award for cinematic box office achievement, a consolation prize for being popular and making money.” In this category, “Barbie” competed against “Guardians of the Galaxy,” “John Wick,” “Mission Impossible”, “Spider Man,” “SuperMario Brothers” and the Taylor Swift movie. (And “Oppenheimer,” to give the category a smidgeon of gravitas.)

Finally (so far), there were the SAG awards, which did manage to disappear “Barbie” completely. Those awards are just for acting, so the most coveted award given was for a film was “Ensemble Cast in a Motion Picture.” Accepting the award for “Oppenheimer” was Emily Blunt in a red dress surrounded by 10 dark-suited men, most of whom I didn’t even recognize as having even been in the movie, let alone constitute an “ensemble.” “Barbie’s” rather more diverse cast? You’ll find them in the shoebox on the top shelf of your daughter’s closet.

Through it all, Gerwig and Margot Robbie were good-humored. Robbie: “We set out to do something that would shift culture, affect culture, just make some sort of impact. And it’s already done that and some, way more than we ever dreamed it would. And that is truly the biggest reward that could come out of all of this.”

All true. But it sure has saddened me to see the most original film of the year—and in many ways, the most culturally ground-breaking—consigned to nothingness at the awards shows.

And then I began to hear rumors that another film might give “Oppenheimer” a run at the finish line. And intriguingly, some critics were comparing it to the outcast “Barbie.”

“One takes place in a bright, plastic world where everything is coated in pink. The other takes place in an isolated black-and-white world that transforms, “Wizard of Oz” style, into a flashy, steampunk domain. Though they’re very different stylistically, the Oscar-nominated films “Barbie” and “Poor Things” are both modern feminist fables about the making of a woman….Both Bella and Barbie are able to fully build and understand their identities when they get out from under the patriarchy and gain access to their inner daughter and inner mother. The point of both stories is that a woman’s freedom lies beyond the neat roles that society would exclusively prescribe her, whether that’s child, wife or mother. To be a free woman, like Bella or Barbie, is to be free of definition — or, rather, to be free to define oneself.”

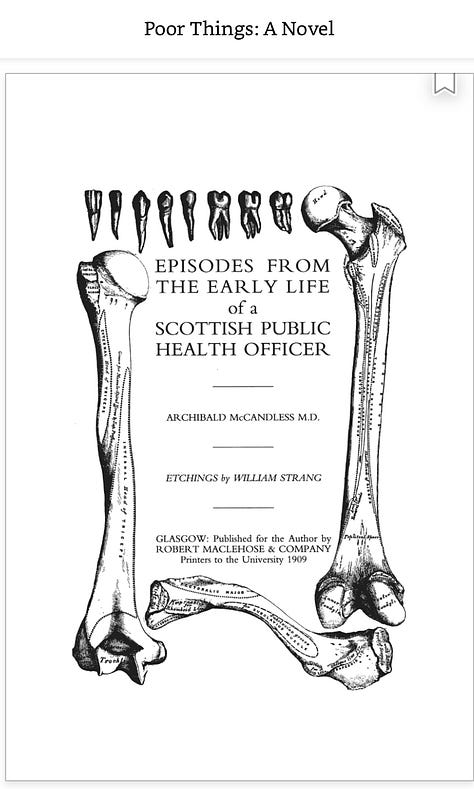

That’s the first and last sentence of Maya Phillips’ March 2 review of Yorgos Lanthimos’s “Poor Things,” a visually stunning, aggressively transgressive and wackily transformed riff on a very strange novel by Alasdair Bray. Emma Stone plays Bella, a young Victorian woman who after an attempted suicide is revived—with the brain of her own fetus implanted in her—by a quasi-demented but fatherly surgeon/scientist (Willem DaFoe, who Lanthimos has decided to make look like an amalgam of the Frankenstein monster and the Elephant Man—one of many departures from the novel.) And from there we follow Bella’s evolution from awkward, spontaneously libidinal toddler to craving, adventurous adolescent to independent, politically-aware, modern woman.

Emma Stone is inventive, adorable and very comfortable being naked, and will likely get the Oscar, if only for the most authentic masturbation scenes ever filmed. (She’s not my pick, though; that goes to the luminous Lilly Gladstone—a tough call, as all the actresses nominated were marvelous.) Mark Ruffalo is what reviewers like to call “a revelation”—usually so warmly and solidly masculine, here he lets himself go into a role that requires him to be an amoral—but also clever and never menacing—seducer at the beginning and a decomposing, weepy little boy by the end—and to perform a bizarre dance midway. The weirdness, the amazing settings, the humor, the terrific performances, and the “I dare you to be a humorless prude” challenge that Lanthimos seems to be issuing, has dazzled critics.

Some, like Maya Phillips, have drawn parallels with “Barbie”—with one difference. It’s through the awakening and abandonment to her vital, sexual self that Bella “discovers what she wants, and claims her agency to pursue it” while for the genital-less Barbie (Margot Robbie) the evolution is “more abstract” (I’m not sure that’s the right word for the discovery that ones feet are permanently malformed.) Both, however, as Phillip sees them, are “fables” of “female empowerment.” And throughout her review there is much talk of “agency,” and “autonomy”—cherished postmodern feminist keywords, and a nice justification for Academy members who disappeared “Barbie” but vote for “Poor Things” to prove that there is nothing sexist about their preferences.

There’s an unusual amount of nudity in “Poor Things.” (For me,” Lanthimos says, “that aspect was never an issue. Sex in movies, or nudity — I just never understood the prudishness around it. It always drives me mad how liberal people are about violence and how they allow minors to experience it in any way, and then we’re so prudish about sexuality.”) But “Poor Things” is not just healthily unabashed about sexuality. For much of the movie, Bella is not an “empowered sexual woman,” but a child having sex with grown men. As such, she doesn’t seem as much of a sexual agent, as we—the viewer—feel like we’re peeking through the keyhole of the bedroom of a little girl who’s poking around her body and doesn’t know she’s being watched. And the fact that Lanthimos has chosen an actress with a mini-breasted, colt-legged, Lolita-like body to play her enhances whatever titillation is provided by her naïveté. (In the novel, she is described as having a tall, voluptuous body.) It’s not just “the male gaze” (which of course women can inhabit, too) that finds her so erotically enchanting—it’s the Humbert Humbert-gaze. Which is itself a variant, often found in sci-fi movies, of what “Pop Culture Detective” calls the “Born Sexy Yesterday” trope: the spontaneous, unselfconscious child-in-a-woman’s-form who is both innocent (and thus in need of male tutelage) and deliciously sexually responsive:

To the extent that “Poor Things” can claim to be a “modern feminist fable” it’s because the movie ends with Bella, having escaped from the clutches of the men who try to possess her, pursuing a career as a doctor and happily studying for her anatomy exam, lounging in the garden with her (also doctor-to-be) female lover, as well as the once-servile maid who is now treated as an equal, the husband-buddy who is the only man to honor her autonomy, and an inherited menagerie of genetically altered animals. (I had to look away whenever they were on screen.)

The novel, I was fascinated to find out, ends very differently. In the novel, the narrative that forms the entire frame of the movie turns out to very possibly be the literary creation of an unreliable, unhinged narrator, whose version of events is followed by a corrected account by Bella (now known as Victoria McCandless) left to be discovered by a future reader. (By 1974, she has no surviving descendants.)

“Doctor Vic” (as we are told in footnotes) was a suffragist, a socialist, and an advocate of birth control; she may also have been secretly been performing abortions. And in her version, the implanting of a fetal brain and the weird adventures that follow are nothing but a florid Victorian fantasy concocted by her husband Archie:

“You, dear reader, have now two accounts to choose between and there can be no doubt which is most probable. My second husband’s story positively stinks of all that was morbid in that most morbid of centuries, the nineteenth. He has made a sufficiently strange story stranger still by stirring into it episodes and phrases to be found in Hogg’s Suicide’s Grave with additional ghouleries from the works of Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filched from? I find traces of The Coming Race, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dracula, Trilby, Rider Haggard’s She, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes and, alas, Alice Through the Looking-Glass; a gloomier book than the sunlit Alice in Wonderland. He has even plagiarized work by two very dear friends: G. B. Shaw’s Pygmalion and the scientific romances of Herbert George Wells.”

The reader, who is also given an introduction and a (laughable) set of footnotes, all of which together comprise the fiction that is the novel, is left to decide which account is most believable: the one that is animated by Victorian male fantasies or the one in which a mature, accomplished woman deconstructs those fantasies. I think it’s pretty clear the one Lanthimos chose, though he rarely mentions the alternative. In the one interview I read in which he vaguely alludes to it, he explains that it wouldn’t have worked with the comic mood of the movie. He’s probably right about that. Deconstructing masculine fantasies and being funny at the same time—without lecturing to, condescending to, or alienating male viewers—takes a genius like Greta Gerwig.

I also admired:

“Anatomy of a Fall”

While “Oppenheimer” tells us what to think in virtually every scene, “Anatomy of a Fall” deliberately avoids giving the viewer a clear resolution on anything, including the circumstances of the titular fall. The ambiguity, however, is not just to keep us guessing. It has a point.

It’s billed as a “thriller” but I saw it more as a deconstruction of familiar, comfortable film tropes about relationships, according to which one is either falling in love, or in a “happy together period,” or falling apart, for one reason or another.

The “thriller” part is whether Samuel, whose dead, bloody body has been discovered (by their son, visually-impaired and deeply perceptive Daniel) at the bottom of their three-story mountain cabin, has fallen by accident or been murdered by his wife, Sandra (Sandra Huller.) In court, the prosecution plays a tape that Samuel had made, unknown to Sandra, recording a blistering fight between the couple. In it, Samuel, frustrated by his inability to write, blames Sandra for leaving him with responsibilities for Daniel, while she (Germanic, stoic, with apparently with none of the blocks that torment the more volatile Samuel) pursues her own writing. It starts as a verbal argument, but eventually turns physical. Wine classes are broken, Sandra hits Samuel, and hell breaks loose, during which either Sandra slaps Samuel repeatedly or he slaps himself (the court only has the audio.)

Many women will identify more with Sandra’s frustration at being blamed for not doing what is expected of a wife than with Samuel’s petulance. But that (feminist) point isn’t driven home. Rather, it’s the (apparent) violence that is underscored. It shocks the courtroom, and Sandra’s lawyer is appalled that she hadn’t told him about the fight. But for Sandra (although her husband is French, she is the true post-structuralist of the two) “that recording is not reality. If you take an extreme moment in life, an emotional peak, and focus on it, it crushes reality. It may seem like irrefutable proof, but it actually warps everything. That is not reality. It’s our voices, but it’s not who we are.”

When Samuel’s therapist testifies about Samuel’s view of Sandra as “castrating” and self-absorbed, Sandra responds to him not with righteous feminist anger but with what to my mind, is the truth of most fights between couples, particularly if the relationship is long-standing. (I’m not talking about one-sided, repetitively abusive behavior.) They are rarely definitive; rarely “fatal,” but a snapshot in (painful) time. If we believe Sandra’s account, by the next day things were back to “normal” between them, their resentments and even violent impulses folded into ongoing life. (Unfortunately, Samuel’s is cut short.)

These comments of Sandra’s are, in a sense, what Anatomy of a Fall is all about. When long-standing, intimate relationships are concerned, there are no completely explanatory assessments or conclusions. Perhaps that’s why the film never does provide explicit detail as to what happened to Samuel. Between Sandra and Samuel—and between Sandra and Daniel—feelings flow back and forth, sometimes things are very clear, sometimes obscure. It’s fascinating to watch as it all unfolds. Just don’t try to nail it all down.

Sandra Huller is among the nominees for Best Actress for her performance in “Anatomy of a Fall.” This was an award I would be happy to see given to any of the actresses (Huller, Annette Bening, Emma Stone, Lily Gladstone, Carey Mulligan) nominated. What particularly impressed me though, about Huller was not so much her performance in “Anatomy of a Fall” alone as her ability to transform from the very contemporary Sandra to the Nazi wifey of “The Zone of Interest.” It’s an amazing shape-shift. The way she moves, hands on hips, stiffly divested of everything softly sexual about a woman’s body, officiously puttering about her luxurious home and garden, imperious with the servants, giggling over coffee with the other Nazi wives, she knows both her place—but also her value as a member (and reproducer) of the master race. I don’t know how Huller figured it out—maybe from old newsreels or movies—but even her posture seems exactly right.

“The Zone of Interest”

This was nominated both for “Best Picture” and for “Best International Feature” and will almost certainly be awarded the latter. Aesthetically, it’s unlike any of the other nominated films (actually, unlike any other films at all—at least, that I can recall) in that it totally rejects the use of close-ups and artful camera-work and cinematography (angles, transitions, lighting etc.) to emphasize a moment or make a psychological or moral point. Its more detached, “anthropological” view made me aware of just how much “telling” (as opposed to “showing”) there is in most movies. Those who have seen the film will know exactly what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, this “anatomy of a scene” feature with director Jonathan Glazer will help:

When I saw “The Zone of Interest,” I couldn’t help think about how differently “Oppenheimer” and “Zone of Interest” represented the mass murders perpetrated by the Americans, on the one hand, and the Nazis, on the other. I’m not talking about controversy over whether the use of the bomb was “justified” or not—that’s a topic for a whole other piece—but rather, the difference in the way the two films asked the viewer to imagine the human horrors taking place out of view of the main action.

In “Oppenheimer,” the human reality of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are barely featured (the “big” moral question raised by the movie concerns the future of the bomb, not what it has already done.) When the Japanese do make an appearance, it’s only as intrusive images—oh, so briefly, a shredded face, a charred body invade Oppenheimer’s mind as he’s giving a speech celebrating the dropping of the bomb—that signal to the viewer Oppenheimer’s deepening moral qualms. And as such, they are there to say more about Oppenheimer (such a good man, he’s already tormented by what he’s done, while the audience, cheering and foot-stomping, is ecstatic) than the human reality of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In “The Zone of Interest,” the camera doesn’t take us into anyone’s mind; the main point of the movie is how oblivious they all are to the humanity of those inside the camp. But the viewer isn’t allowed to be. Throughout virtually the entire film, we hear and see what lies outside the walls of the Hoss’s house and garden: the screams, the gunshots, the arriving trains, the sound (and smoke) of the crematoriums. A piece of human bone is found in the stream in which the Höss family frolics. And we see their frantic efforts to disinfect themselves.

“Oppenheimer” and “The Zone of Interest” are, of course, entirely different kinds of movies. But the story of the making of the bomb is in its own way also about obliviousness to human suffering (Oppenheimer: “My job is just to make the bomb. Not to make decisions about what to do with it.”) Oppenheimer, and many of the others who helped build the bomb, came to regret that obliviousness. But Nolan himself seems far more interested in the moral dilemma raised by the unleashing of the power of the bomb on future generations than on the Japanese. Personally, I found “The Zone of Interest” more chilling.

I’d be happy to see either Jonathan Glazer or Justine Triet (“Anatomy of a Fall”) get the award for Best Director. But it’s probably going to go to Christopher Nolan.

Brief notes on some other nominations:

“American Fiction” and “The Holdovers”: Conventional, enjoyable movies with some great comic moments and wonderful performances. But I’ve seen (or read) some version(s) of each of them before.

“Past Lives”: Made me cry. I actually loved this movie, and if I had to put them in order, I’d probably put it in 4th place, just below “The Zone of Interest”

“Killers of the Flower Moon”: Good movie, but most outstanding, for me, were the performances of Lily Gladstone and Robert DeNiro. Lily Gladstone is a real contender for the Best Actress award. Robert DeNiro, probably not (for Best Supporting Actor.) For my money, DeNiro’s was among the most memorable portraits in smarmy villainy I’ve seen, and I’d like to see him win. But he’s up against Robert Downey Jr., Mark Ruffalo, Sterling K. Brown and Ryan Gosling. I have no idea who will be chosen.

My choice for Best Actor would be Colman Domingo, who is mesmerizing in “Rustin.” But Cillian Murphy is almost certain to get the award.

“Maestro” and Bradley Cooper: I’ve said all I need to say in my stack:

Best Supporting Actress: I’m sorry, but I can’t choose (and lucky for me I don’t have to) between Da’Vine Joy Randolph (“The Holdovers”) and Jodie Foster (“Nyad”.) I predict Randolph will take the award.

Best Original Screenplay: “Anatomy of a Fall” (Justine Triet and Arthur Harare) because “Barbie” didn’t make it into this category. But I also do love the under-appreciated “May December” (Samy Burch and Alex Mechanik):

Best Adapted Screenplay: “Barbie” (Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach.) It doesn’t belong in this category, and it’s up against some strong contenders (“American Fiction,” “Oppenheimer,” “The Zone of Interest,” and “Poor Things”) but I’d be shocked if they don’t at least give “Barbie” this award.

“I” equals “Oppenheimer,” As Nolan writes Oppenheimer’s parts in the first person.

Susan, loved your look into Poor Things here. Thank you for sharing!!! The bit about liberals hating sex scenes - I can’t. Perhaps if Bella was constantly seeking penetrative sex to achieve orgasm, maybe it would have been more believable but we all know the realities of the orgasm gap. Bella not fearing pregnancy, not bleeding (either through period or first time sex) and the fact that the main character “had to” be oppressed to achieve her goals all just gave me the ick. I kept waiting for the feminism thinking “is it here in the room with us?” 🤣

I'm, frankly, highly disappointed that Godzilla Minus One didn't get nominated for best picture. It's stellar.